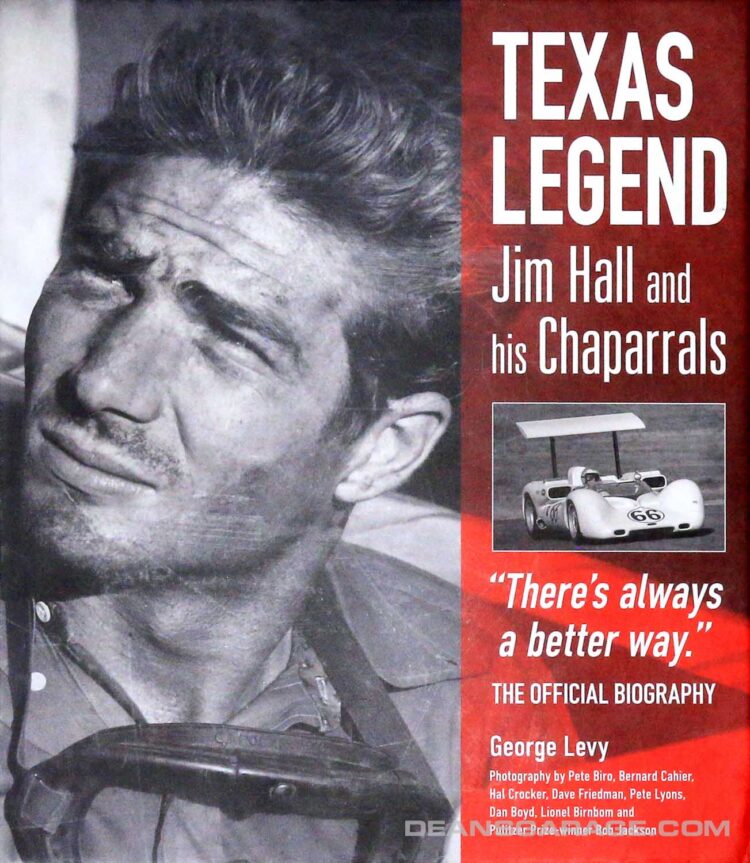

Texas Legend Jim Hall and His Chaparrals

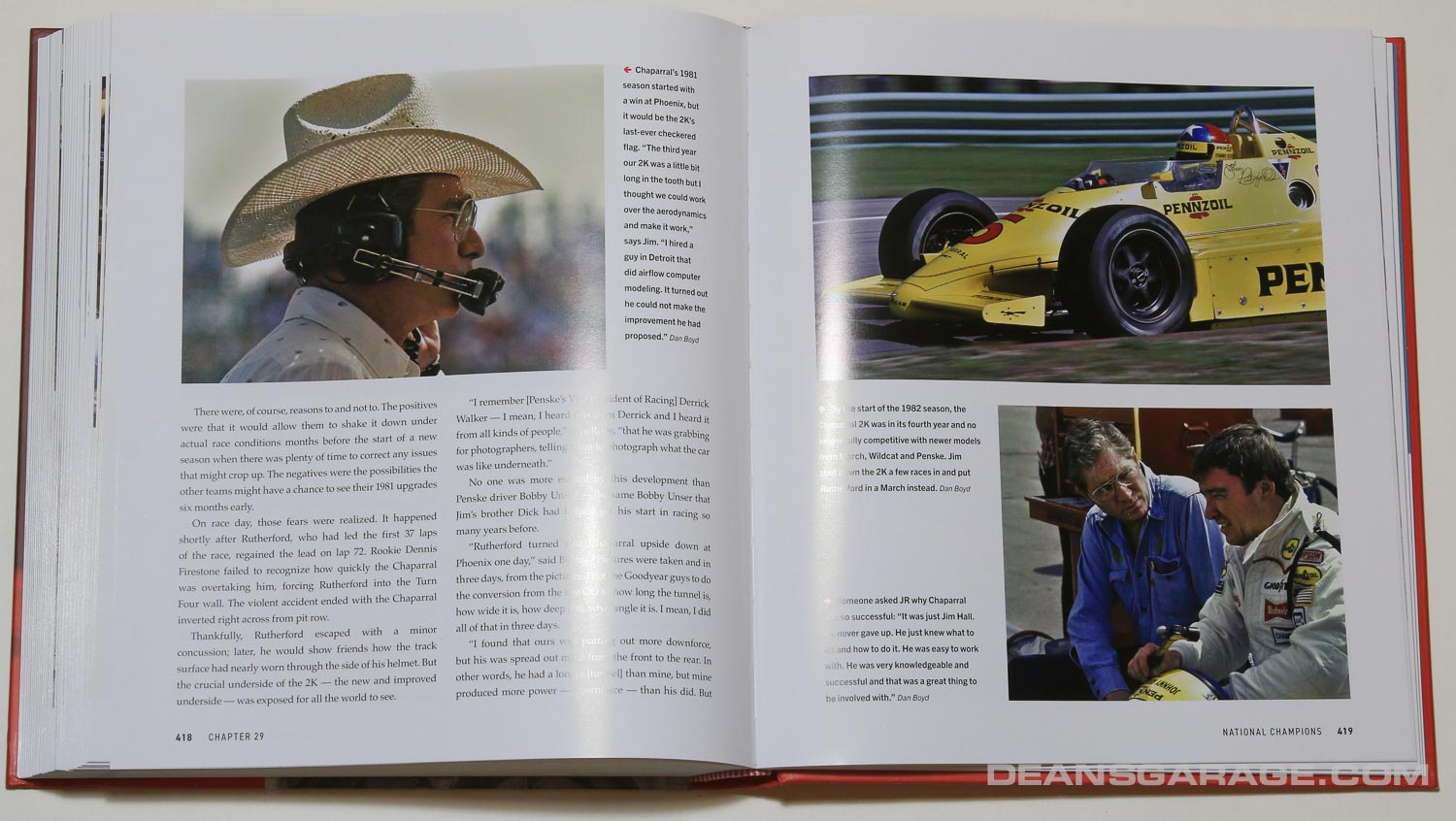

I took this photo of Jim Hall on the first day of qualifying at Indy in 1981 (photos). It’s as close as I ever got to him.

I took this photo of Jim Hall on the first day of qualifying at Indy in 1981 (photos). It’s as close as I ever got to him.

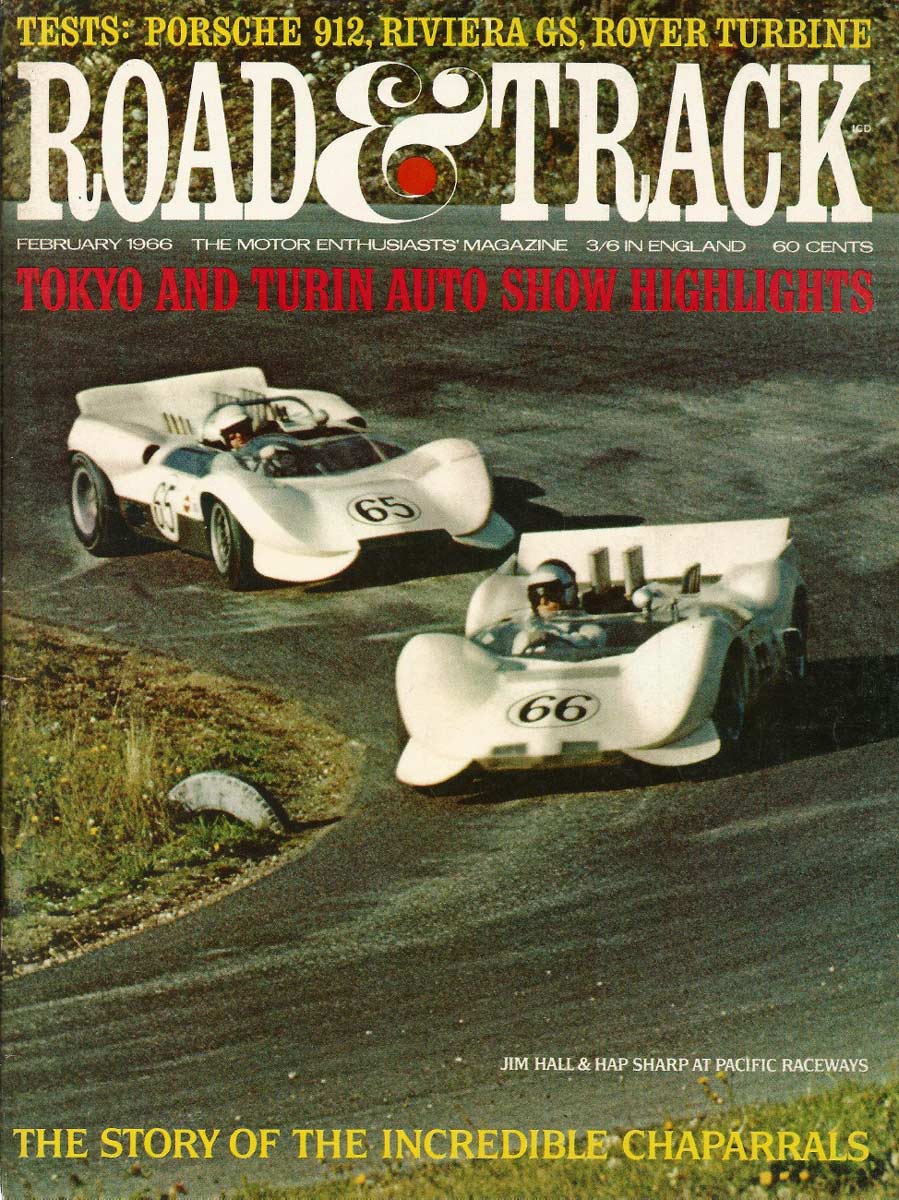

Unless you grew up in the ’60s and were a fan of all things Chevrolet, and lived 30 minutes from the Riverside International Raceway, and were drawn to GM concept cars, in particular the Monza GT, you cannot possibly comprehend the impact Jim Hall’s winged Chaparrals had on me. It was only somewhat comparable to watching the Millennium Falcon go to warp speed on the big screen many years later.

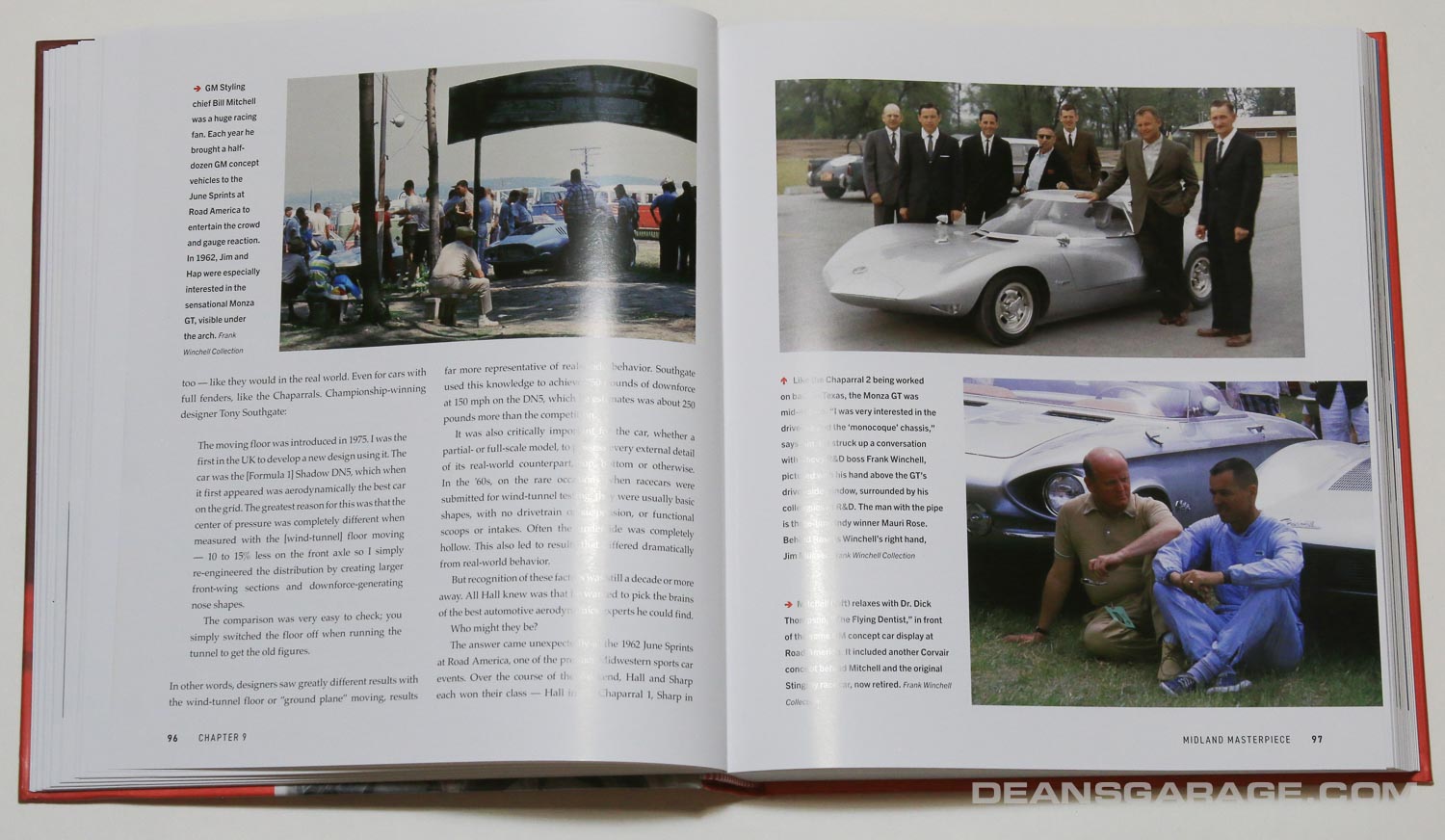

I vividly remember scouting for locations to burn 8mm movie film (movies) around RiR at a USRRC in the early ’60s. I walked over the Champion bridge to get to the end field as Hall’s Chaparral 2 blasted beneath me. Once across, there was under a large tent several GM show cars on dispay, including the Monza GT. The front looked just like the Chaparral! I was mesmerized, so much so that when I got home I wrote General Motors Styling and inquired as to how to become a car designer.

The week before a big race at RIR, I’d scour motel parking lots for race cars. And dealerships. I drove behind DeAnza Chevrolet (which as located in downtown Riverside at the time). Through a fence I could see a Chaparral being worked on in the service garage. Cool.

I was at RIR in 1968 for the CANAM, and traveled with friends to the next race at Stardust outside of Las Vegas. Late in the race I’d run out of movie film. Using binoculars I could follow Hall’s Chaparral 2G around most of the track because the wing stuck high up over the foreground clutter. I watched in horror as I witnessed the back of the 2G rise up into view (just like the famous photo) as he ran into Lothar Motschenbacher’s McLaren that suffered front suspension failure and suddenly slowed. I was devastated.

Jim Hall is a hero to me because he embodies a relentless creative spirit during a time in America where individual initiative was valued and respected.

Now instead of the ultimate run-what-you-brung no-rules CANAM, potential innovation is hamstrung by BOC (balance of performance). Or worse—all the cars are the same (Indy). But I digress.

Jim Hall WAS the CANAM. The beginning of the end was when the wings were clipped, but the fatal blow struck with the 2J’s being ruled out of competition. Now if I could only figure out a way to send Jim Hall my book for his autograph.

Books

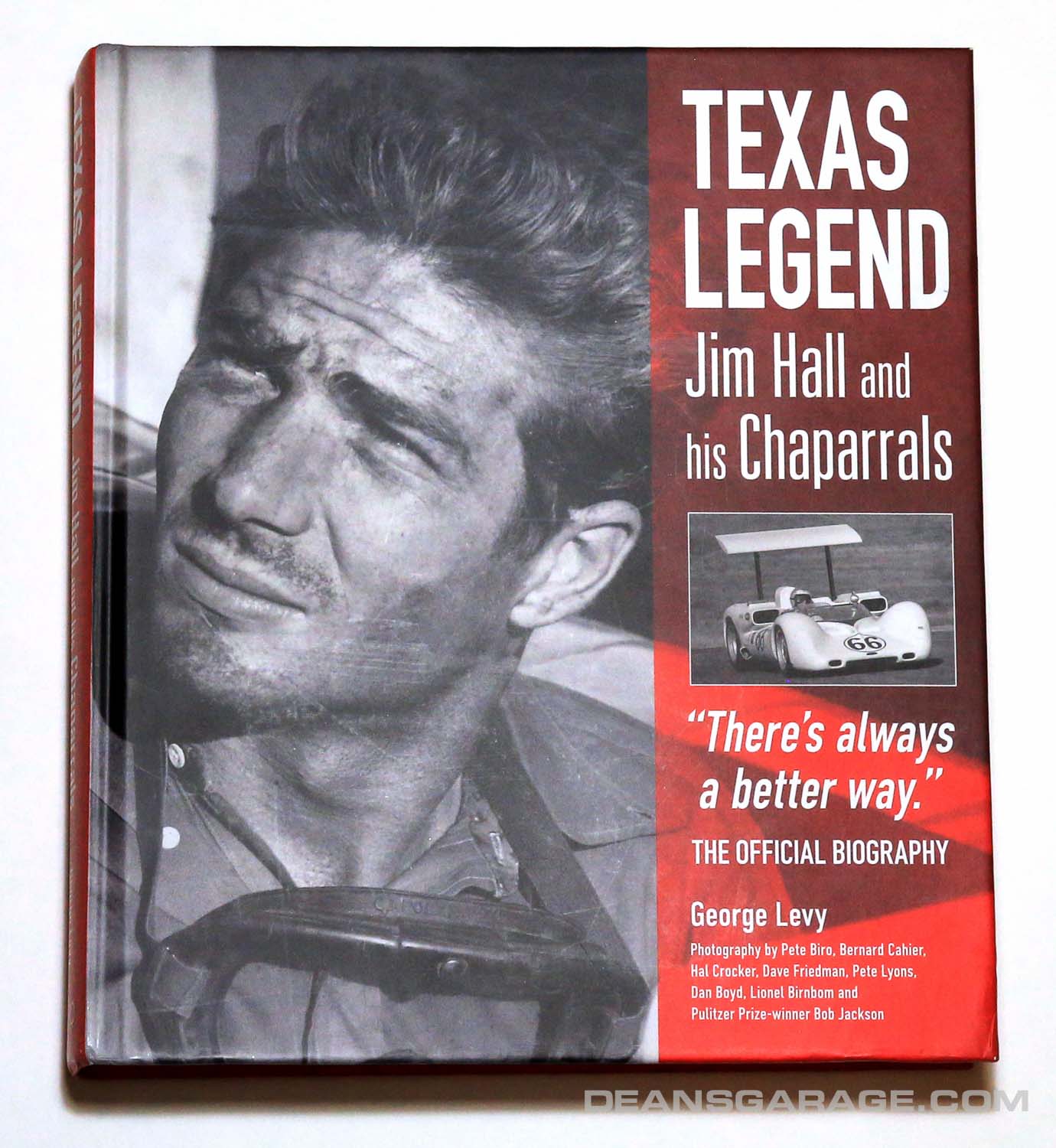

I have several very good books in my library that tell the backstory of road racing in the ’60s and the extent of Chevrolet’s involvement (the reality may surprise you): Chevrolet—Racing, Fourteen Years of Raucous Silence by Paul Van Valkenurgh; Chaparral by Richar Falconer; and The Unfair Advantage by Mark Donohue and Paul Van Valkenburgh. But Texas Legend Jim Hall and His Chaparrals is hands down the best. It tells it like it was, reveals insights as to how the cars were conceived and developed, and dispels rumors that have persisted over the years. It’s a very well written quality publication, professionally designed, hard cover, sewn binding (so it lays pretty flat), lots of white space, easy on the eyes, and has well-prepared photos.

Book Review

I was going to write a comprehensive review, but John Aston of SpeedReaders.info wrote can’t be topped. SpeedReaders graciously allowed me to repost John’s review.

Gary Smith

Texas Legend: Jim Hall and his Chaparrals

“There’s Always a Better Way.”

“There’s Always a Better Way.”

The Official Biography

by George D. Levy

Book review by John Aston

Speedreaders.info

Reposted by Permission

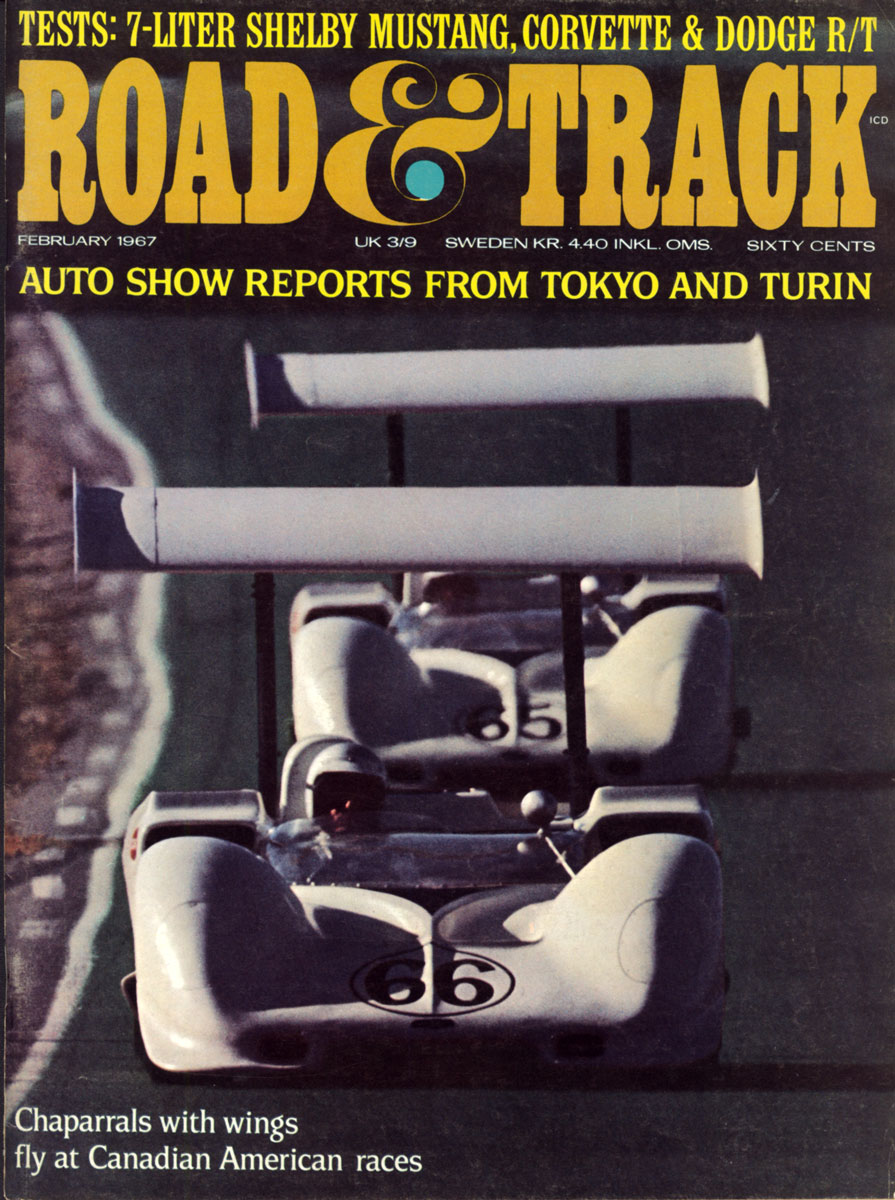

My Christmas present in 1967 was Automobile Year 1967–68. It was a treasure trove of delights, from Ferrari P4 to Eagle-Weslake on track, and from Lamborghini Marzal to Alfa Romeo 33 on the street. But the image most clearly etched into my memory is of the Chaparral 2F blasting through a poppy field on the Targa Florio. To a middle-class teenager in the north of England, the car from Midland, Texas looked like a spaceship—what must it have looked like to the Sicilian who commuted to work on a donkey? George Levy’s 484-page doorstop of a book weighs in at four pounds and tells the story of the man whose vision and innovation changed the face of motor racing.

To understand award-winning author Levy you have to know that he had come away from interviewing Hall for his 2016 book Can-Am 50th Anniversary: Flat Out with North America’s Greatest Race Series 1966–74 (ISBN 978-0760350218) with the realization that his story had never been properly recorded, but also that Hall (b. 1937) was simply not interested in blowing his own horn.

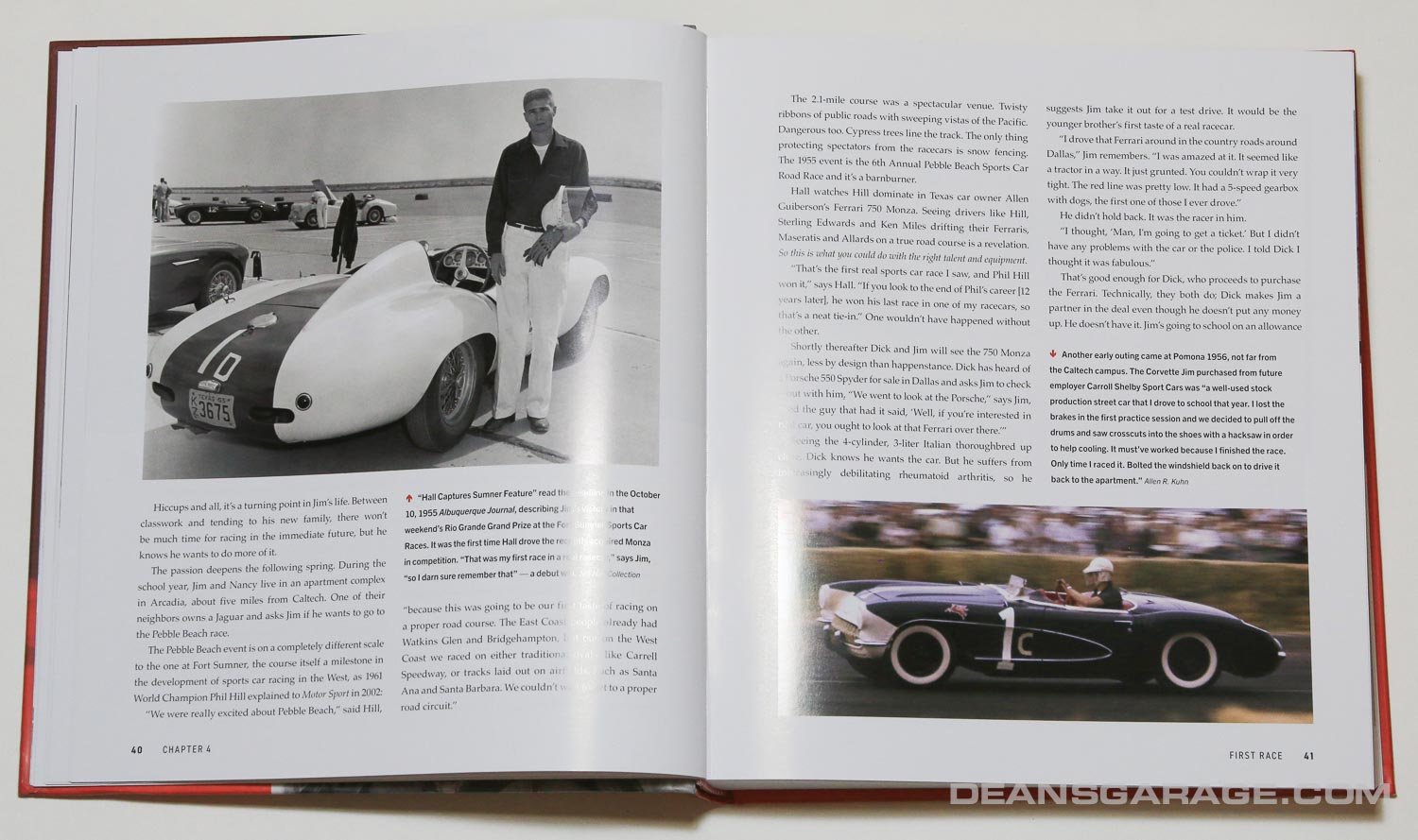

To understand Hall, the author convincingly argues, you need first to understand that Hall identified as a Texan more than an American. In the chapter entitled Don’t Mess With Texas, the author describes what it meant to be a citizen of the Lone Star State.

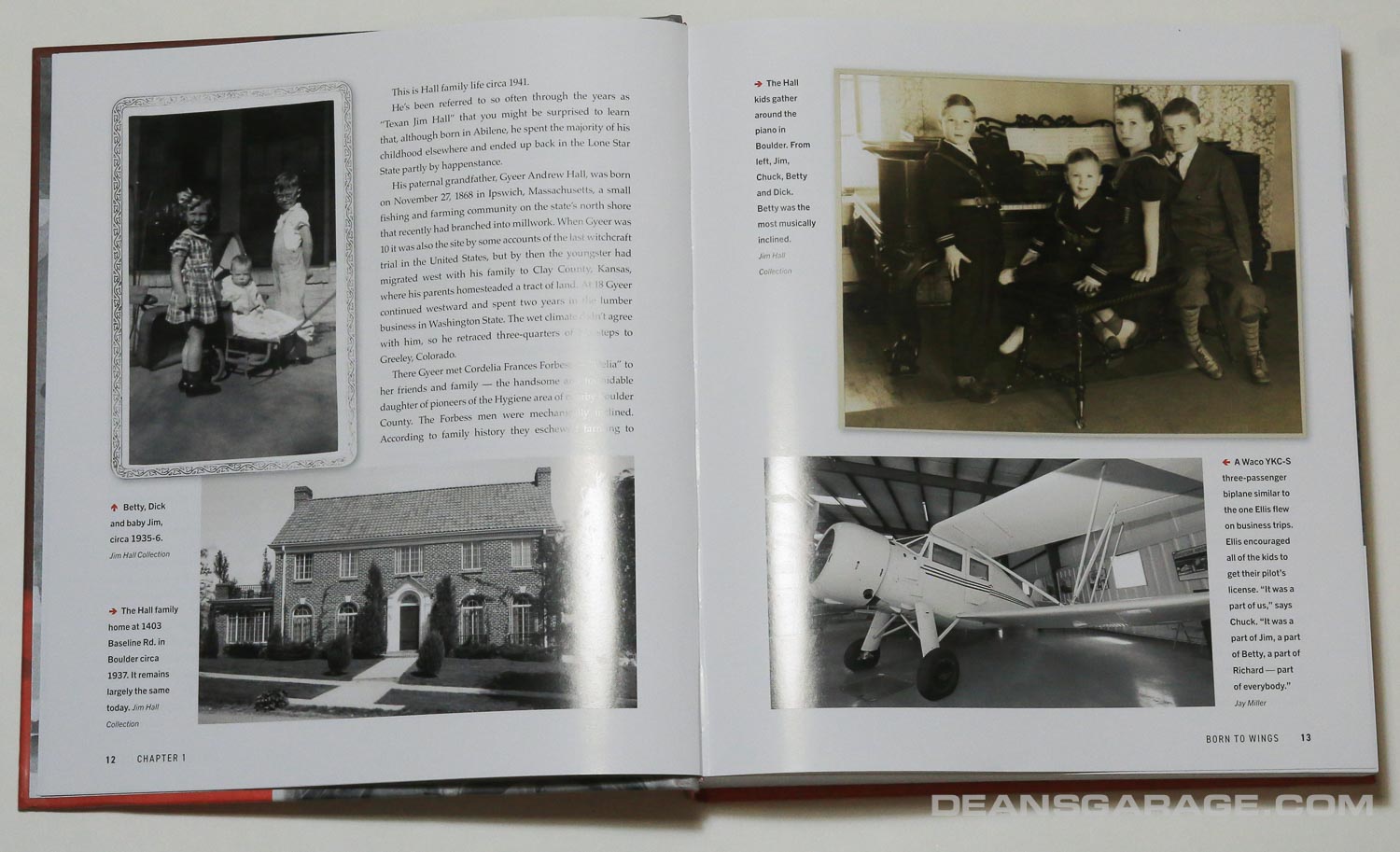

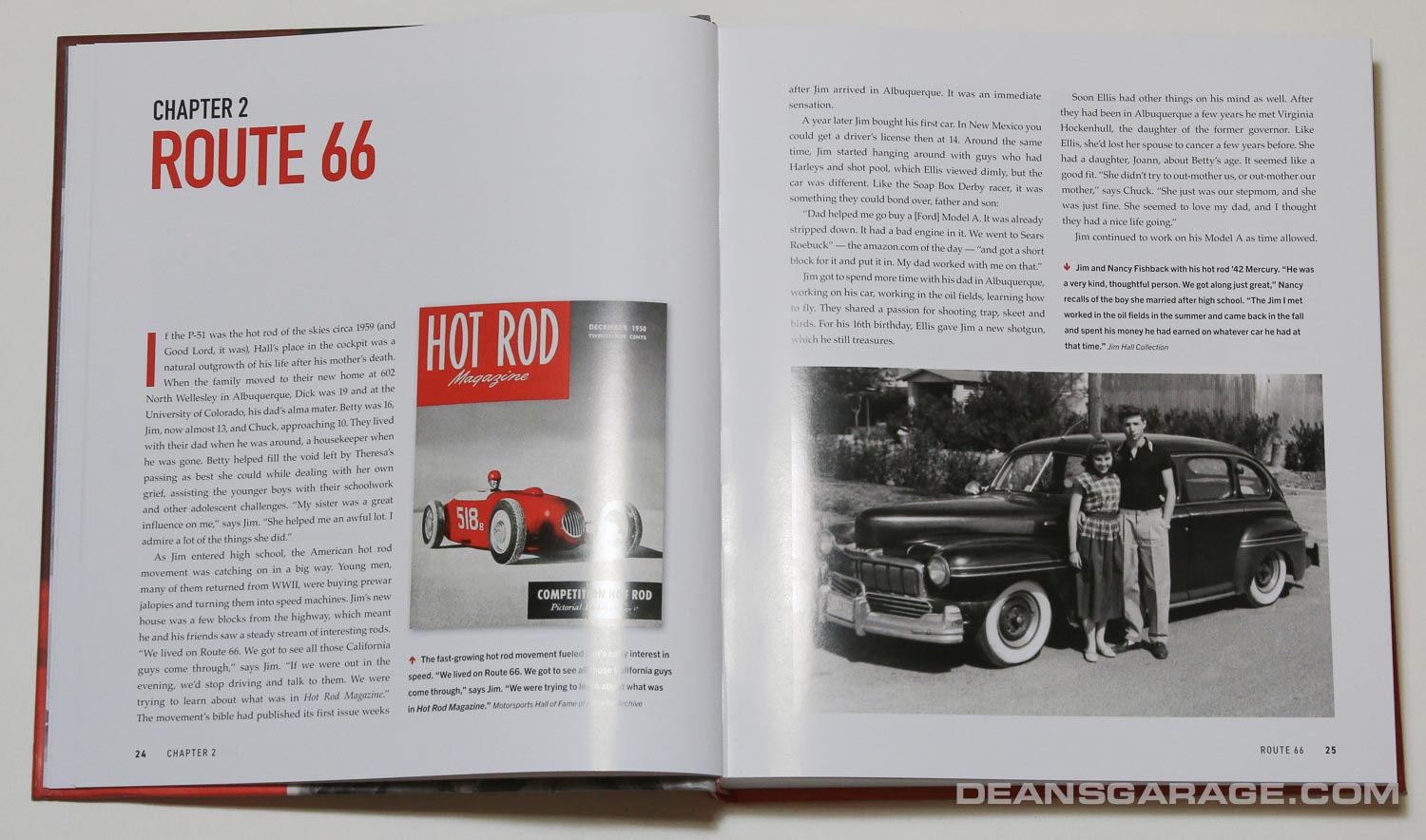

Levy describes Hall as the embodiment of the credo that “people unshackled by taxes and unnecessary regulations could accomplish great things and that individuals who dreamed big and were willing to shoulder the attendant risks—God and Texas, victory or defeat—could change the course of history.” Jim Hall had success baked into his DNA, we learn. He came from a formidably tough, smart and entrepreneurial family, and the boy grew up fast, partly through choice— he married Nancy Fishback at 17—and partly through tragedy—he lost most of his family in a British Columbian air crash six months later. And while Hall’s near counterpart, Lotus boss Colin Chapman, was still modifying prewar Austin Sevens, the Texan was flying his own war surplus P51 Mustang.

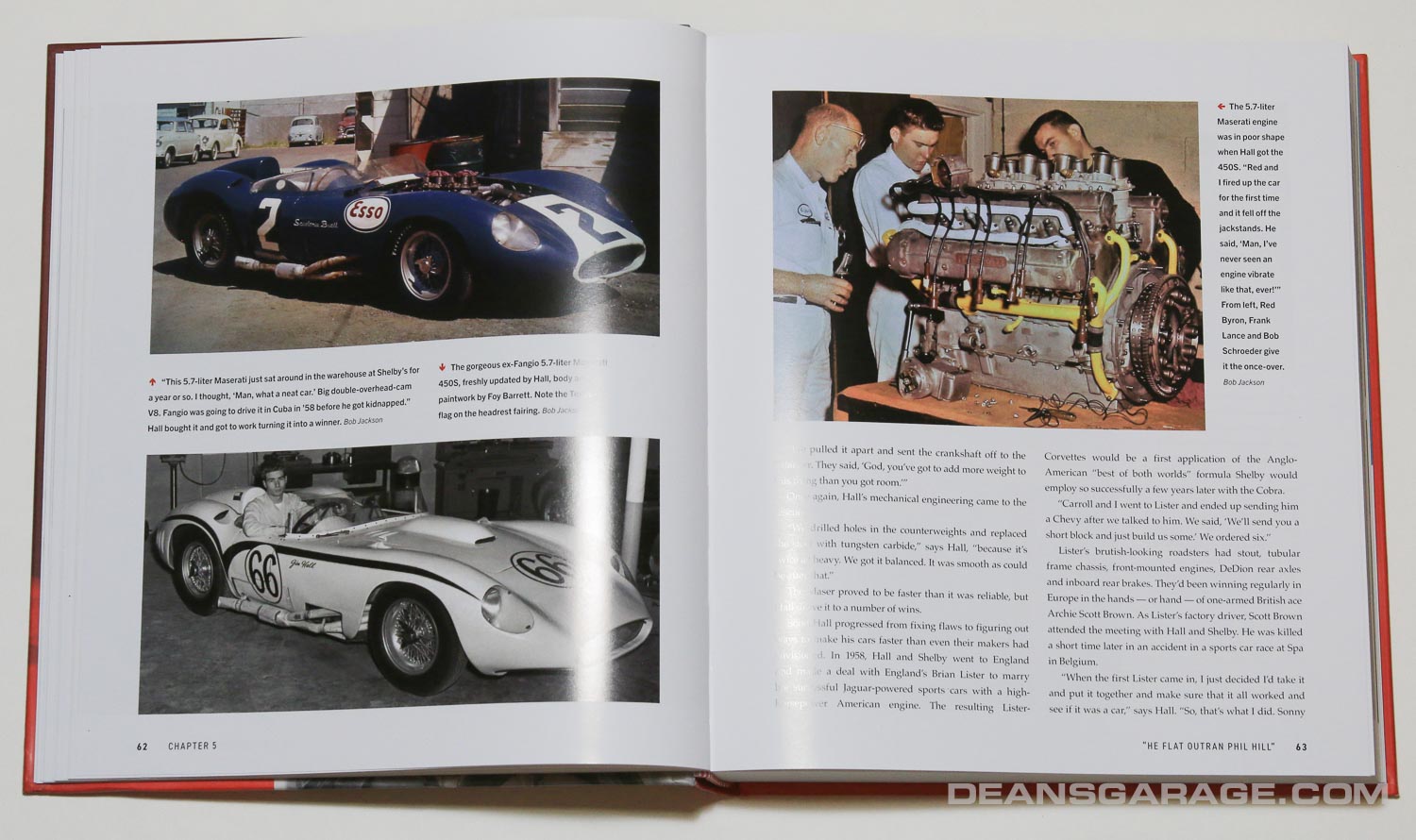

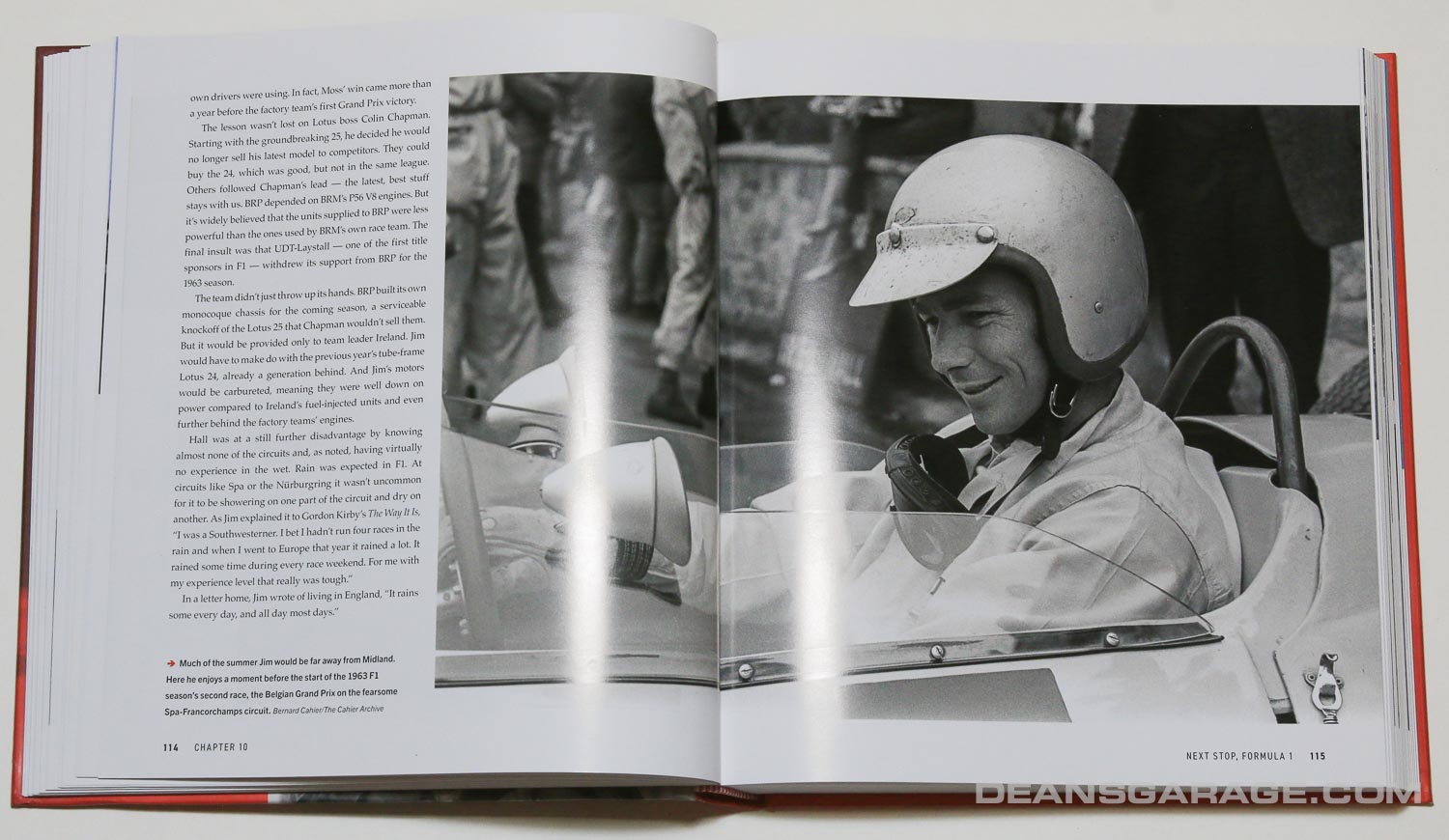

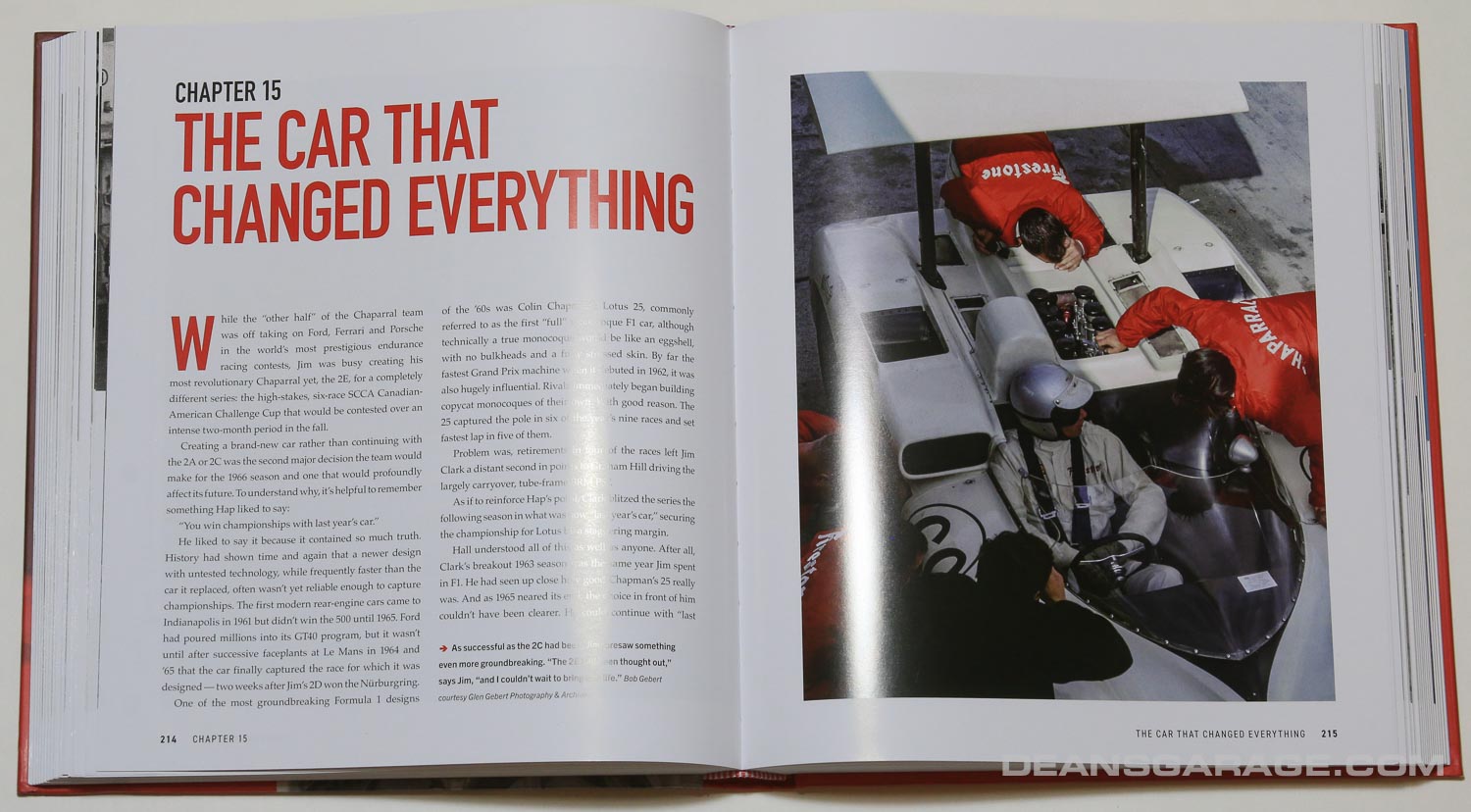

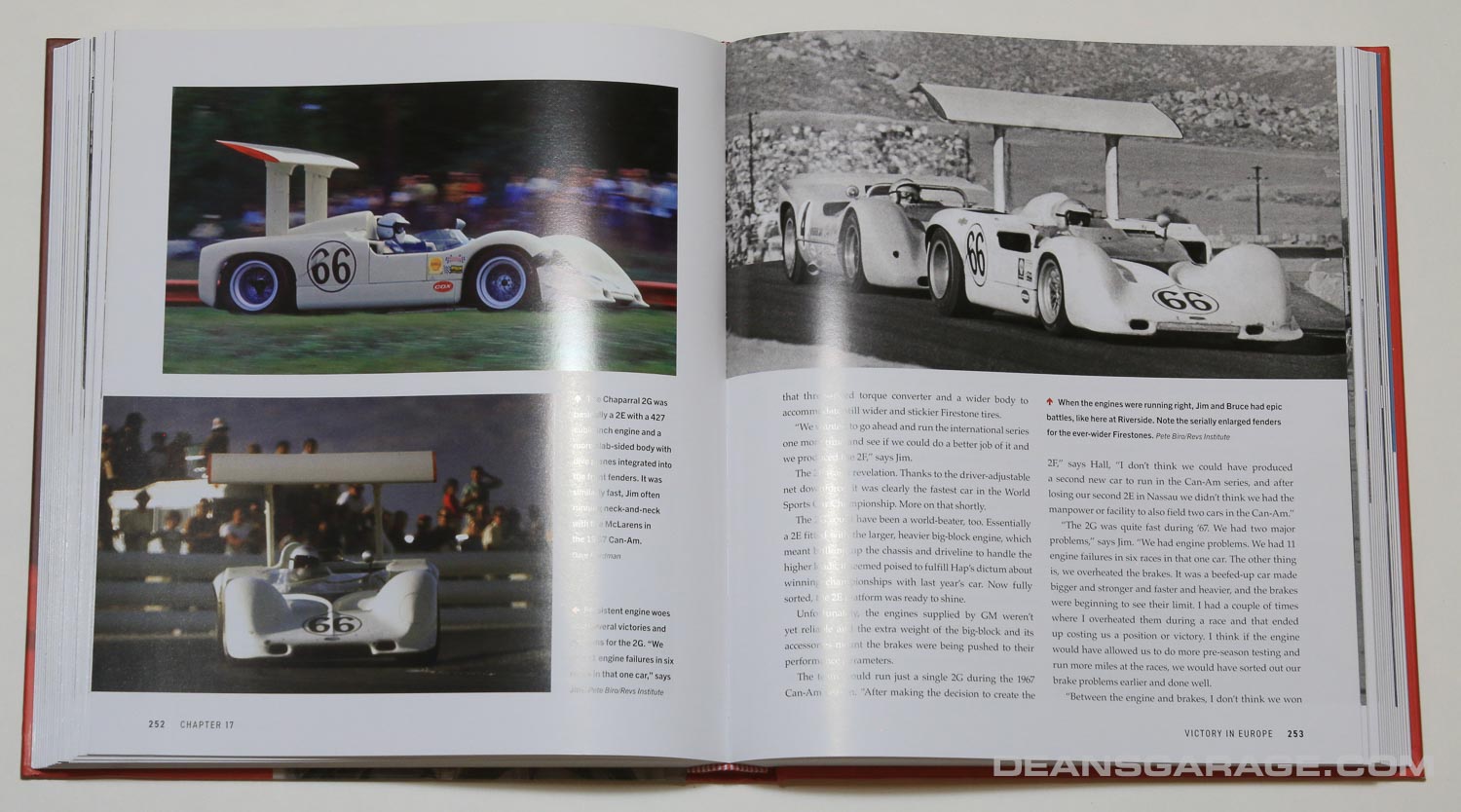

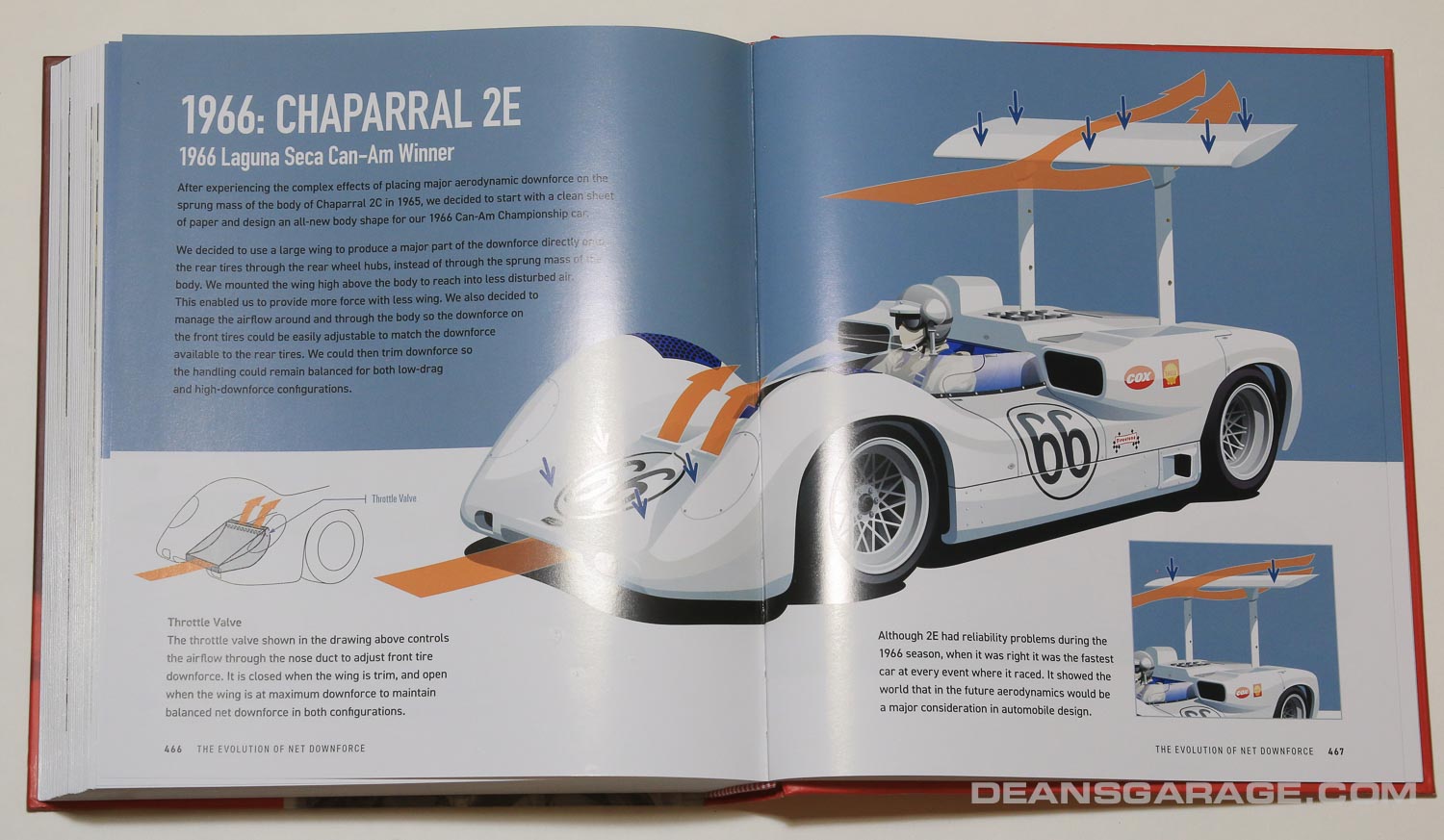

This book emphasizes the two most important facts about Jim Hall and his cars. That he was a good enough driver to compete successfully in Formula One, and that although Chaparral was an immensely influential race car builder, the fact that the last one is called the 2K means there isn’t even half an alphabet’s worth of cars from Rattlesnake Raceway, Texas. In contrast, Lotus was already up to over 90 model types by the time Chapman died in 1982. The contrast between the two geniuses (I will brook no argument) was profound. The mercurial Chapman had no sooner made a breakthrough (notably with the 25, 49, 72, and 79) before he was in hot pursuit of the next “unfair advantage” in the words that serve as Mark Donohue’s epitaph. Hall was always in relentless pursuit of perfection, and his creativity was underpinned by a Texan work ethic that manifested itself in the hard yards he traversed as he researched, designed, tested, refined, and perfected a series of achingly lovely race cars that looked as good as they drove. And don’t forget the side hustles: GM Skunk works, Trans Am and F5000 team boss, and defender of the Corvair’s honor.

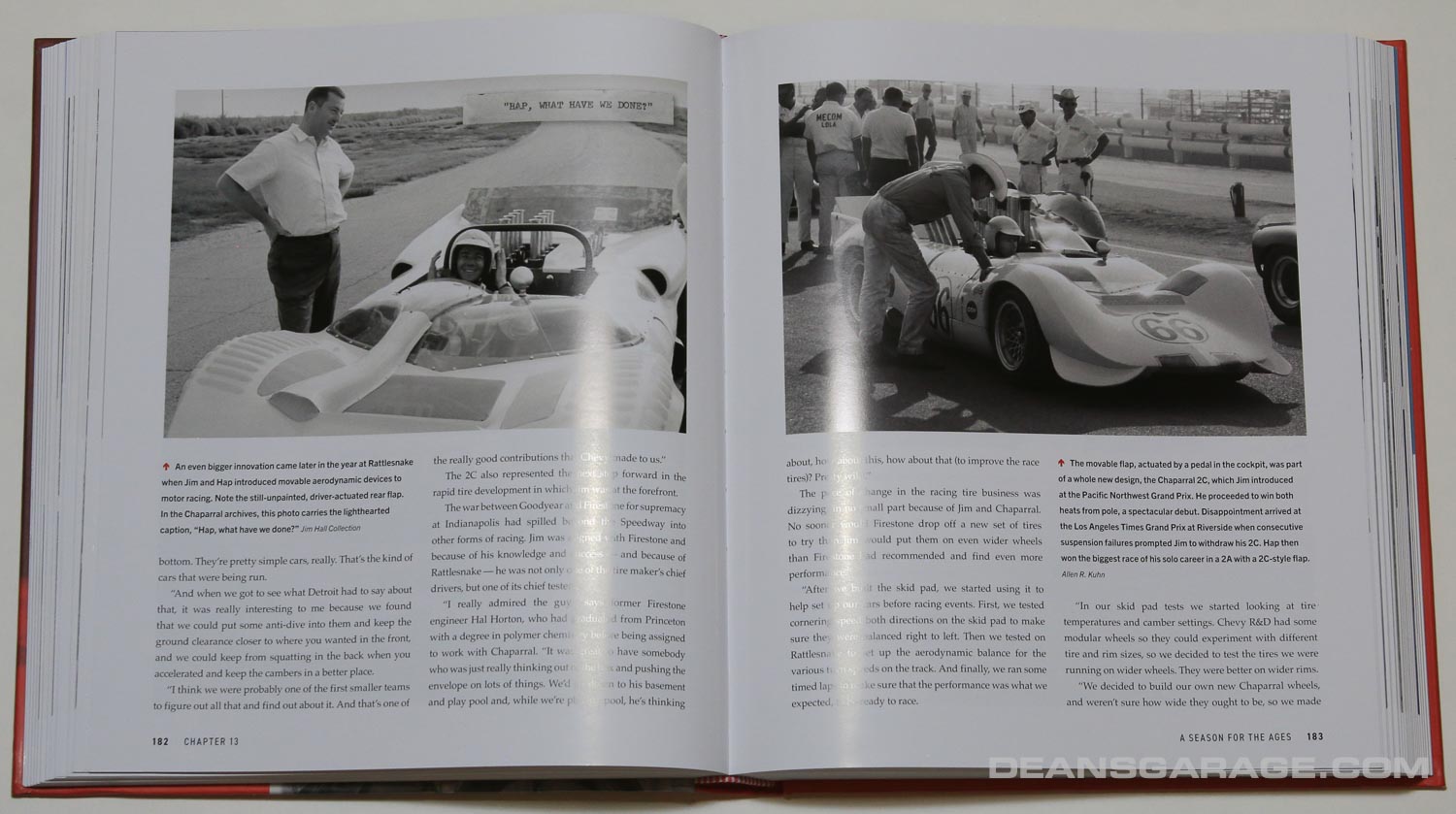

We learn from this wonderfully researched book how the Chaparral ethos was the understanding of aerodynamics and the exploitation of downforce. In his fluid and precise style, Levy takes time to emphasize how Jim Hall’s core mission wasn’t just to eliminate lift (as many contemporaries were doing) but to take a step beyond by creating net downforce. Hall had a physicist’s understanding of airflow but also a visionary spark which illuminated the way forward, from the relatively crude air dam (or splitter in modern parlance) on the Chaparral 2 to the teardrop 2H and the simply astonishing Can Am 2J fan car. He was a serial upsetter of establishment apple carts, as have been his disciples, notably Adrian Newey and Gordon Murray. Especially the latter, whose Brabham BT 46B fan car blitzed the F1 establishment in 1978 and whose T50 road car (also with fan-powered downforce) is wowing the gearhead community in 2024. Those two guys have been almost household names for decades, at least in the United Kingdom and Europe (whom we left, you might have heard?). But Jim Hall exemplifies the message of Mark 10: 32–34, which is to say he remains a prophet without the honor he undoubtedly deserves. Composites construction, aerodynamic downforce, ground effect, and semi-automatic race car transmissions all had their genesis in the race shop located in the hot, arid plains of West Texas. The Ford v Ferrari film introduced a whole new audience to the sports car wars of the Sixties, but how many new fans are aware that it was not the GT40 Mk 2 that first vanquished the European aristocracy from Maranello and Stuttgart, but the Chaparral 2D at the Nürburgring 1000km in June 1966?

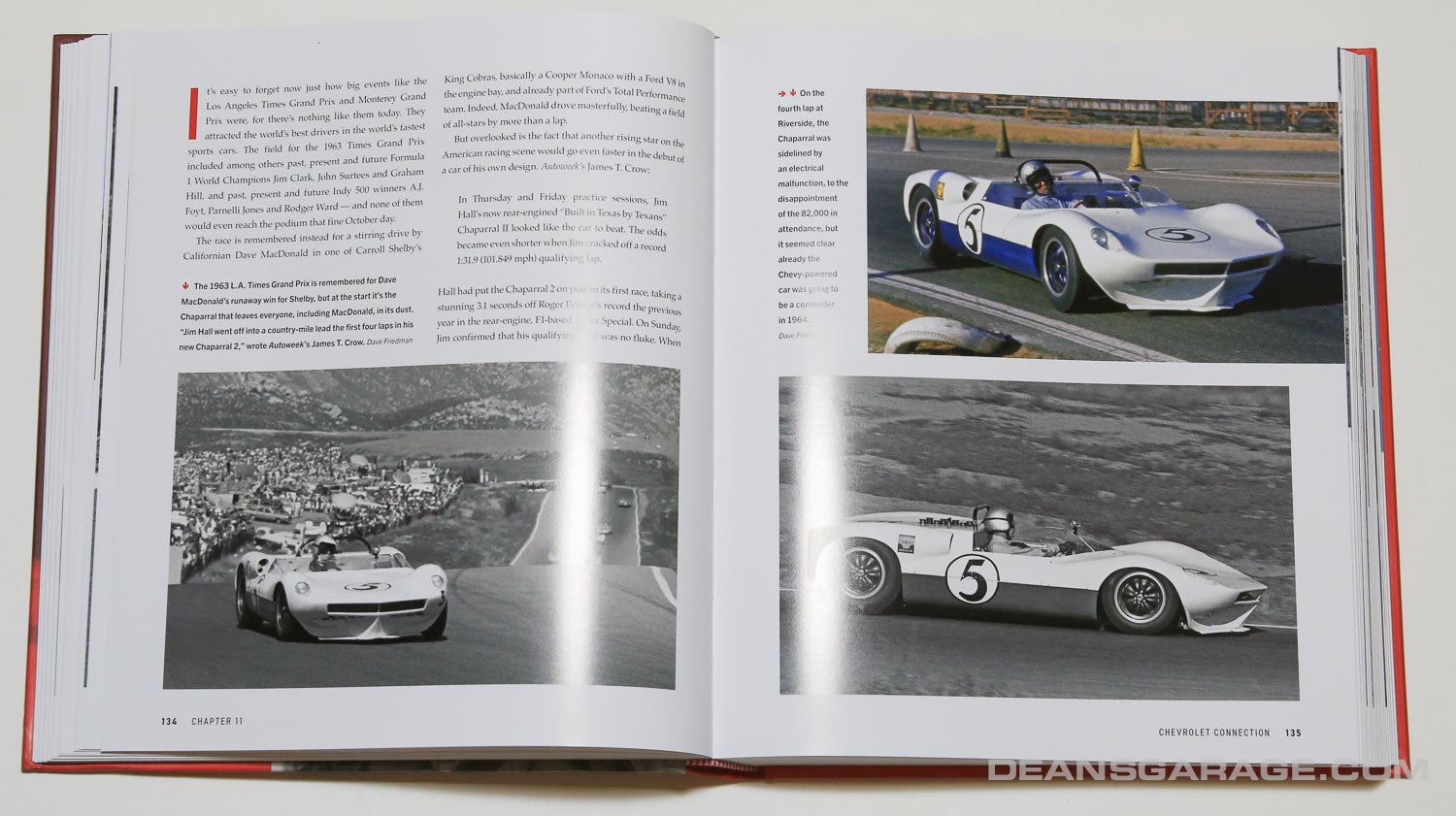

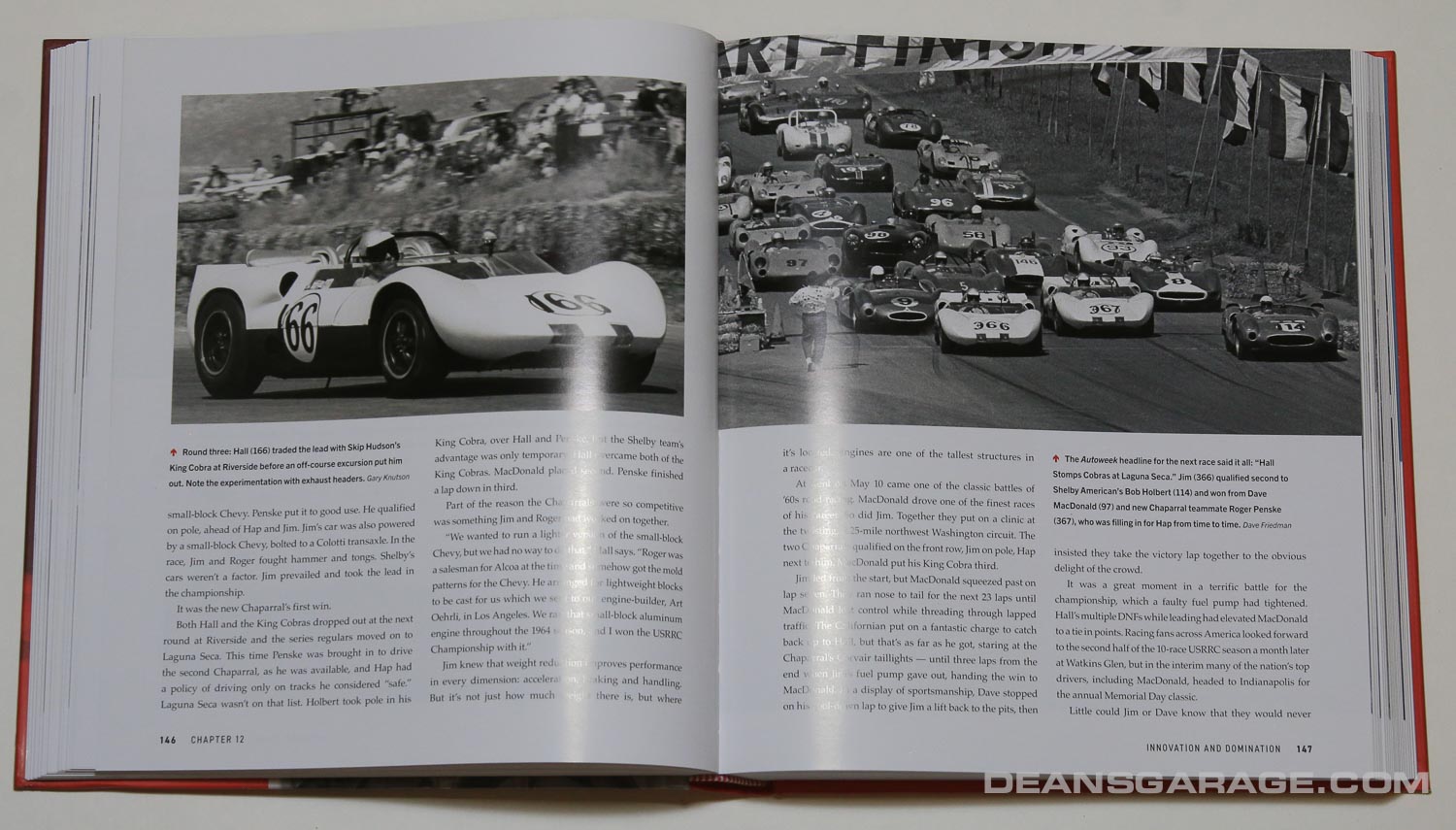

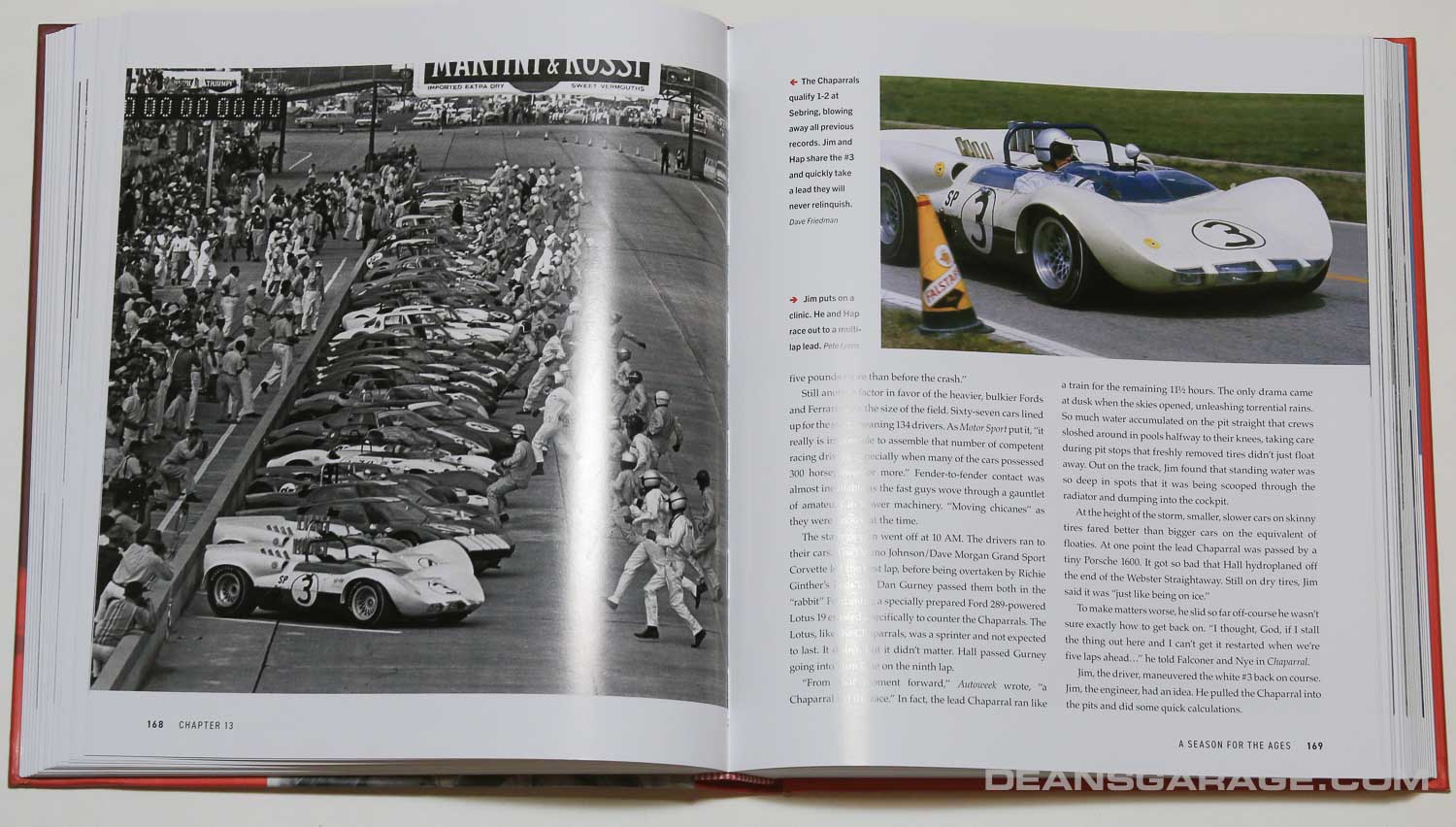

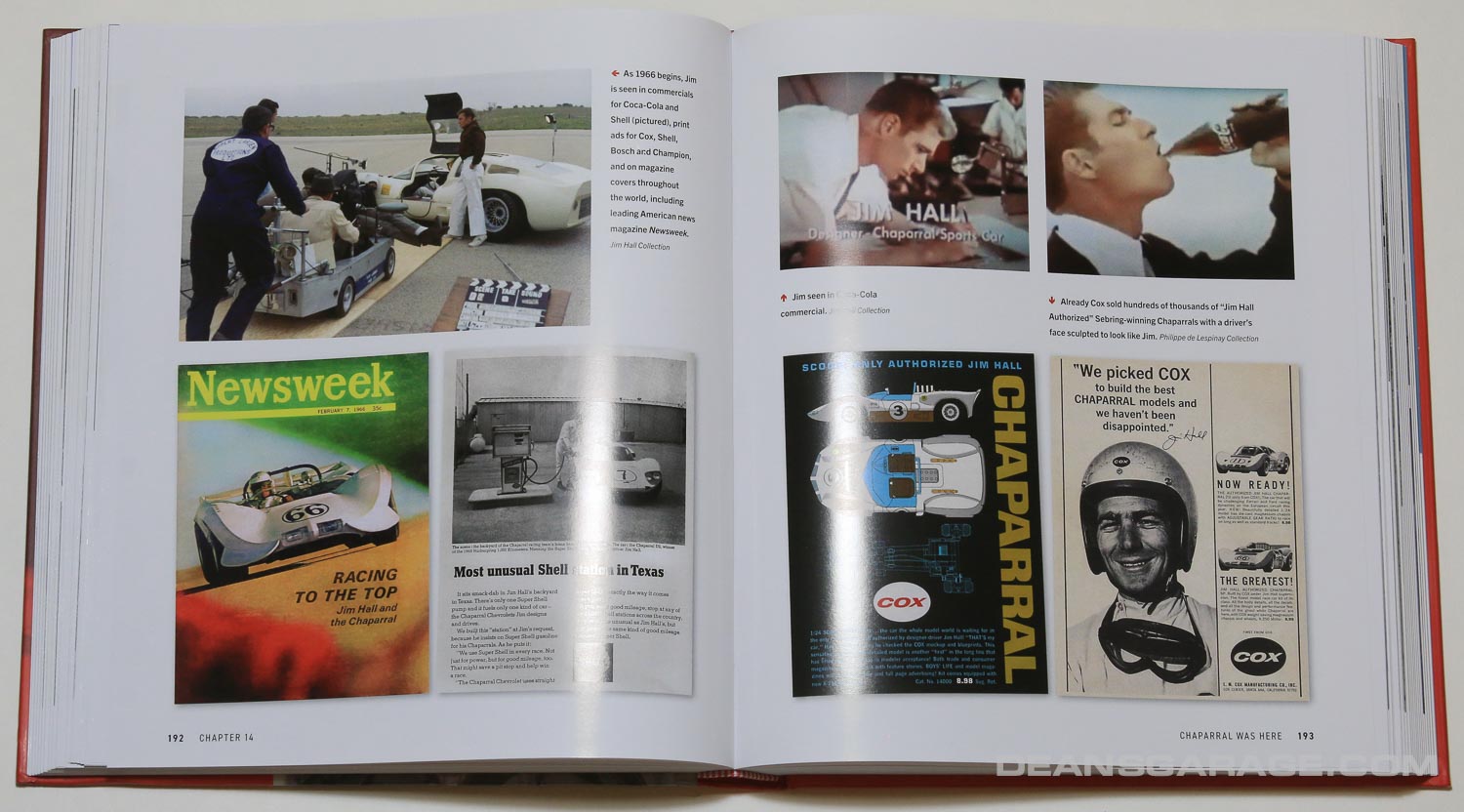

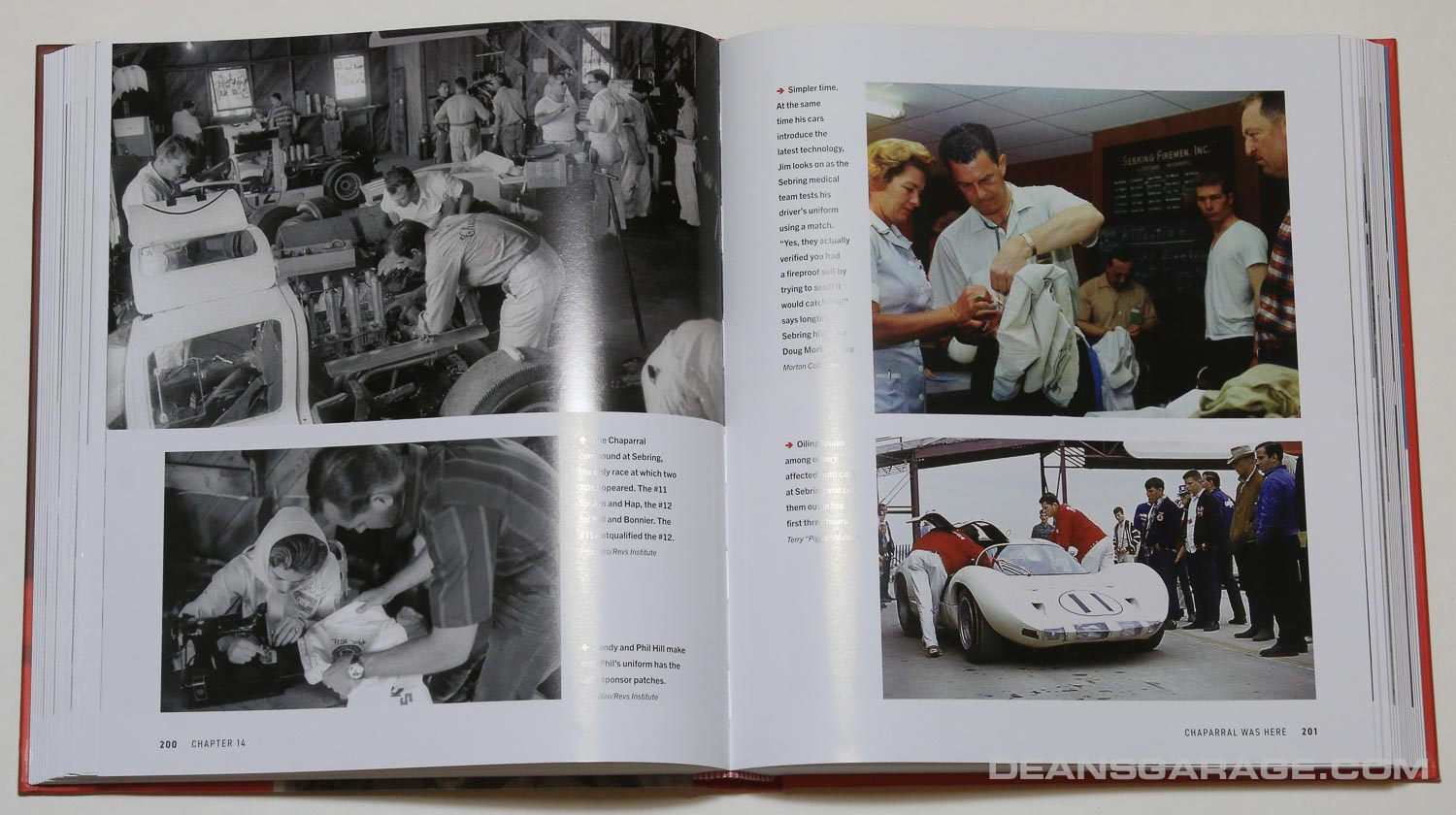

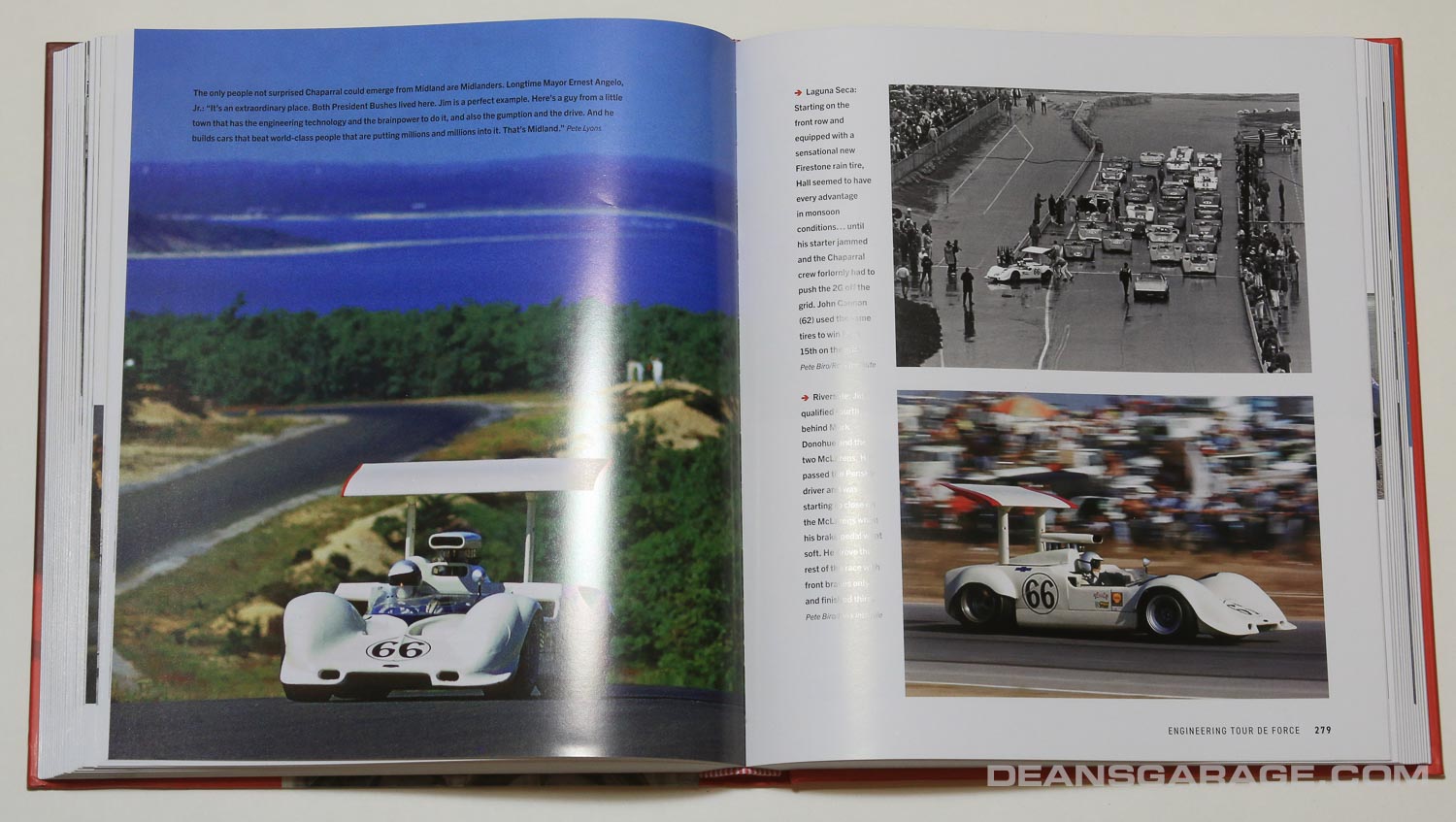

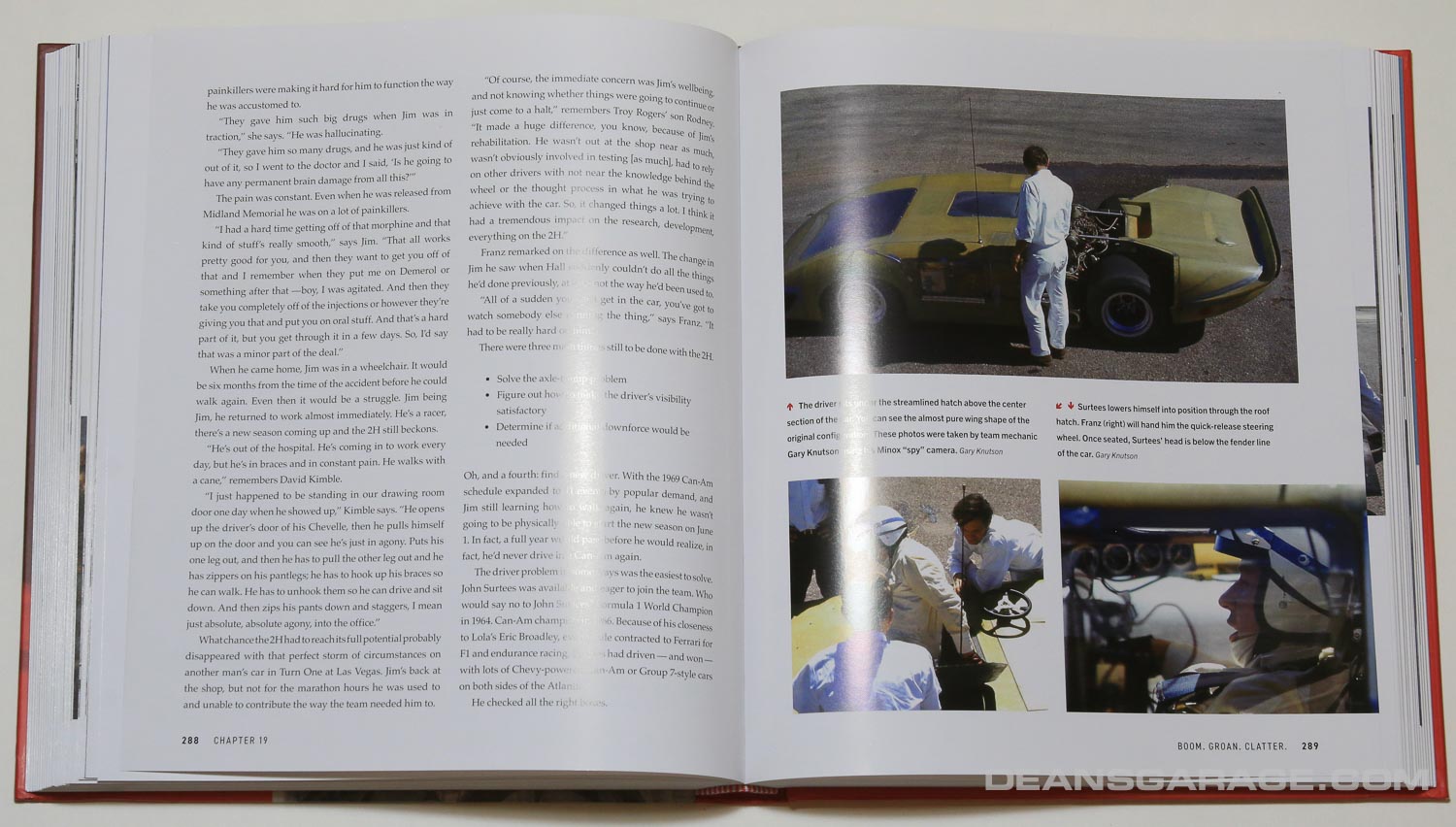

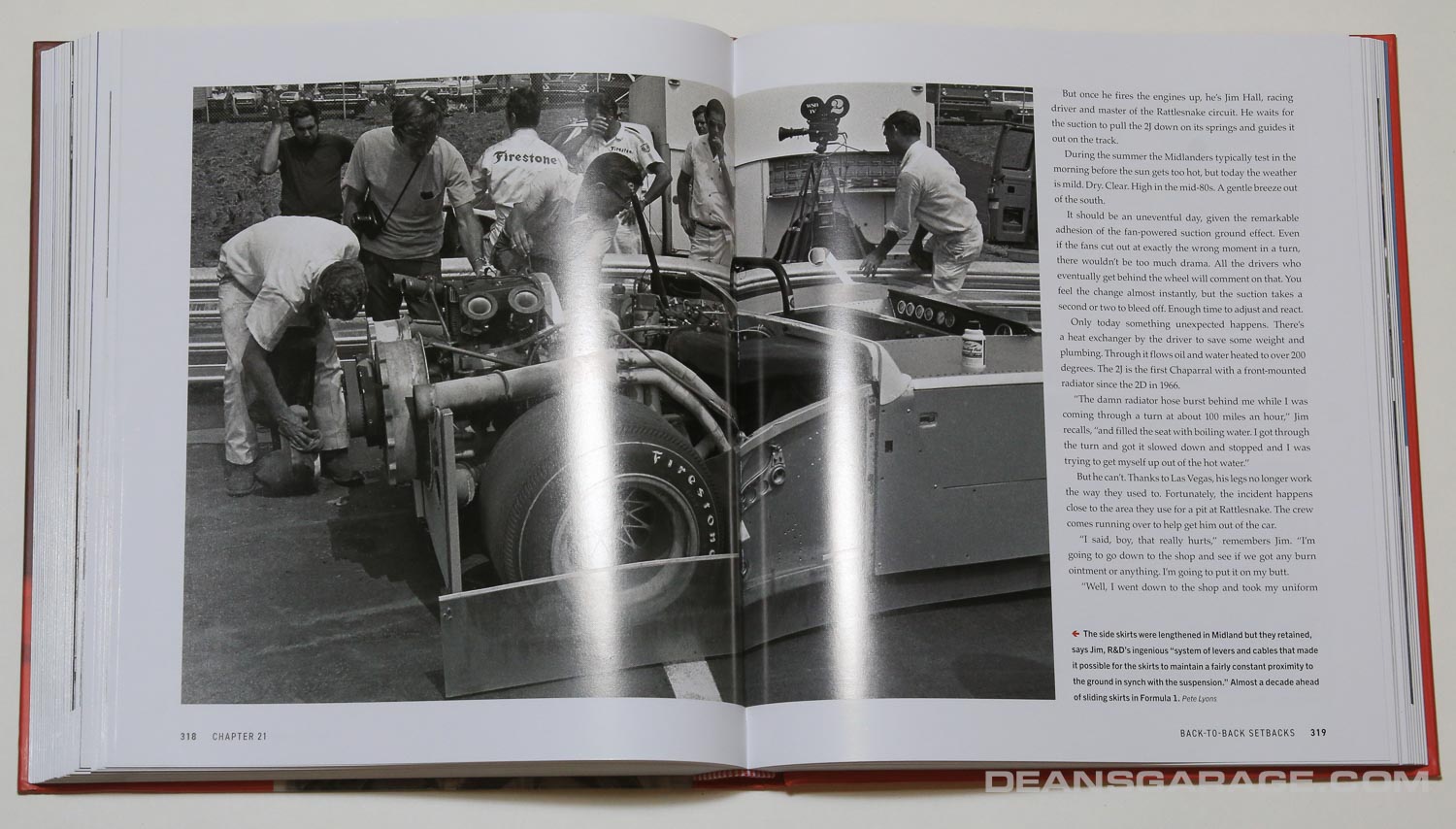

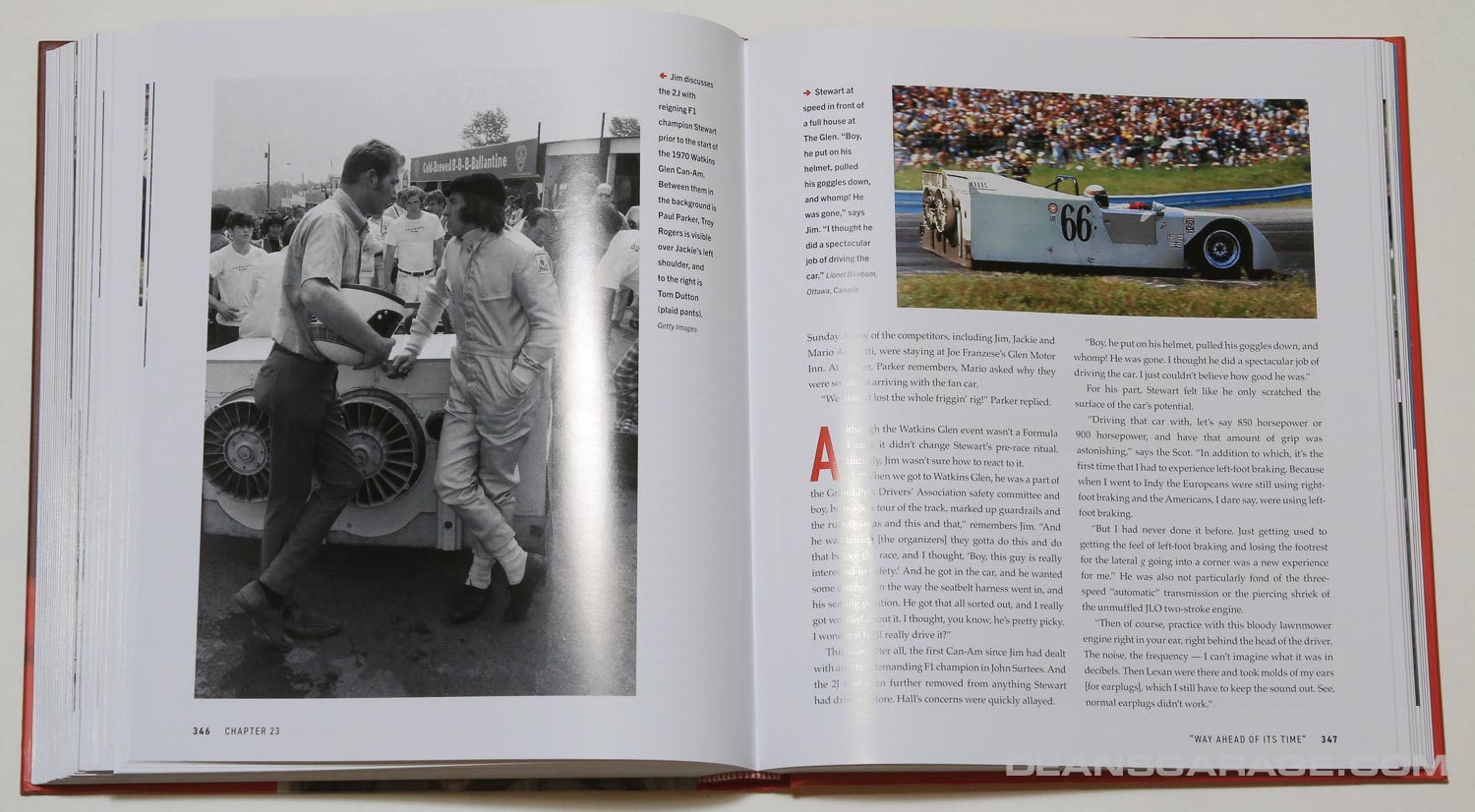

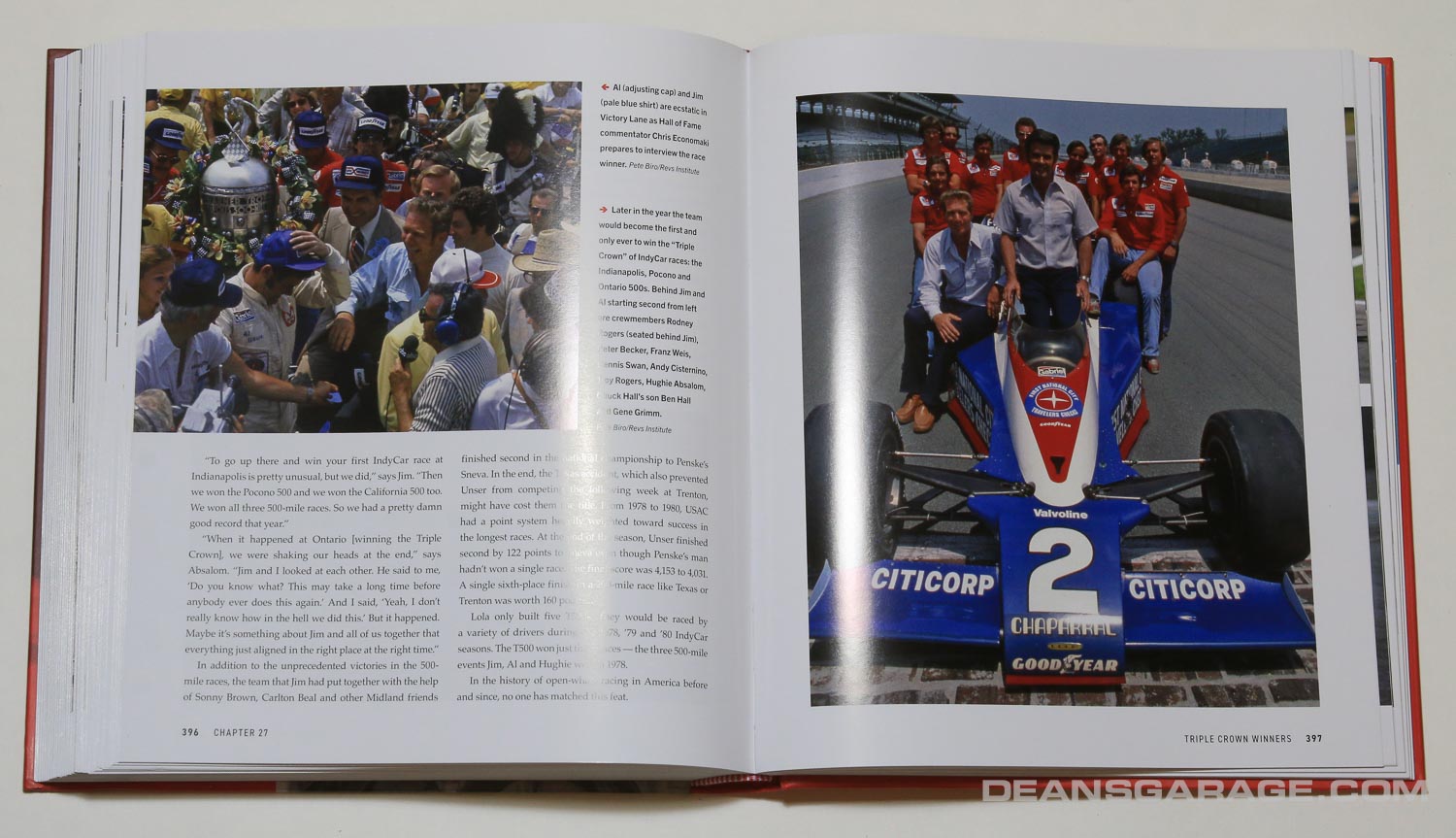

The book has nearly 500 photographs, as befits this most photogenic of marques. White race cars rarely look good but, in common with the 1965 Honda F1 car (RA 272), white Chaparrals are arrestingly beautiful and there’s a host of pictures here to prove it. And along with pictures of the catwalk queen Can Am and Sports Prototypes there are quirkier images to enjoy, such as the picture of the Chevy Corvair being stability tested by firing hydrogen peroxide rockets bolted to its flank. No, I didn’t make that up:

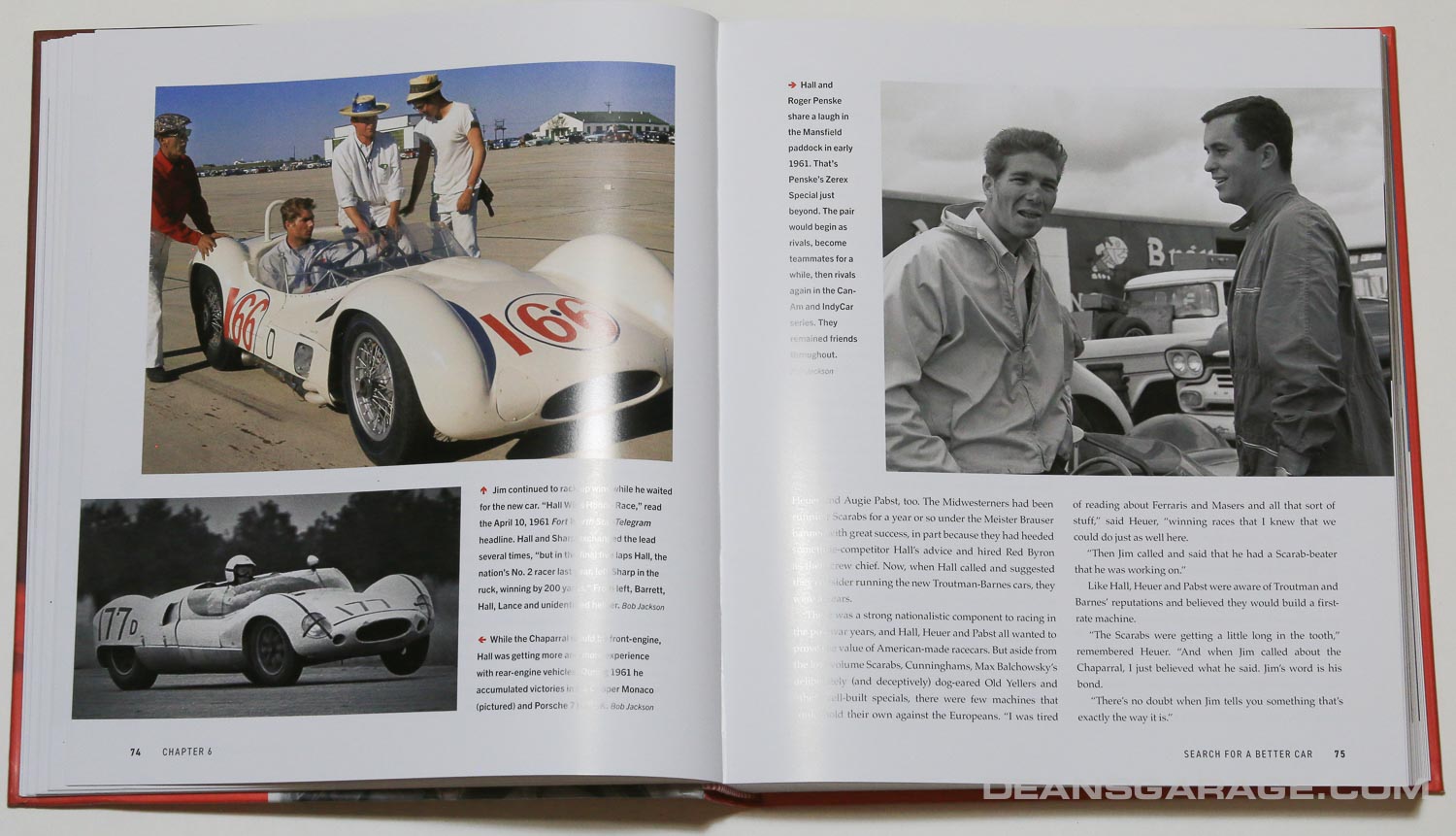

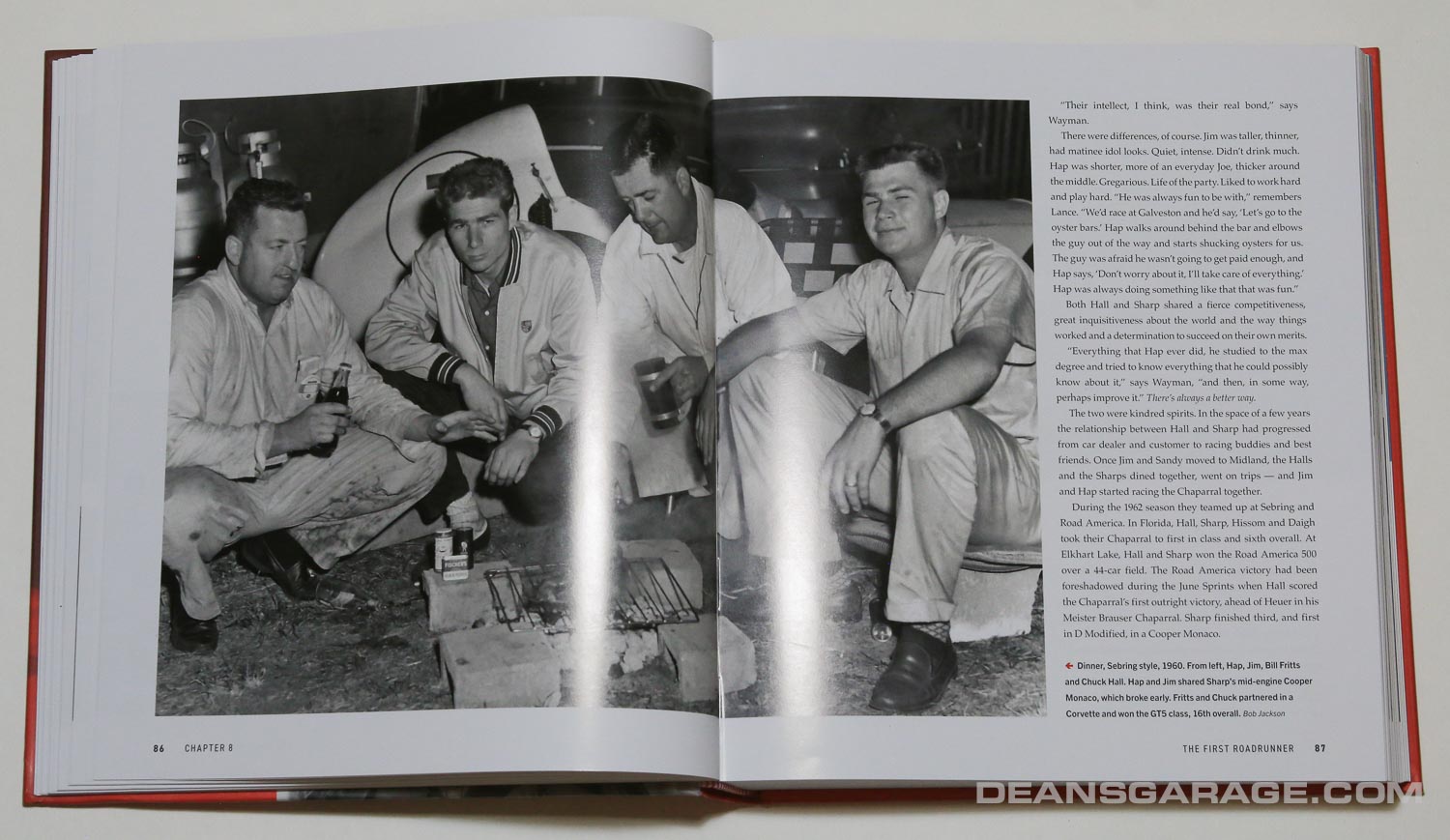

But it’s the images of the people that add flavor and texture to the book. I loved the b/w imagery of this band of tough guys—square jawed, crew-cut Texan racers epitomizing conservative American values and aesthetics. I’d wager that the Chaparral soundtrack was more Patsy Cline than Patti Smith, more Buddy Holly than Buddy Miles.

There’s so much to enjoy in this book that it’s not easy to pick a highlight. If pressed, I’d nominate the story of the 2J, arguably the most “out there” race car in history. Two engines, massive downforce and so iconoclastic that, as the author colorfully describes events, “At The [Watkins] Glen the Chaparral had gotten the rest of the field’s attention. After Road Atlanta they were reaching for torches and pitchforks.” And even Hollywood would have rejected the 2J’s origin story as being wildly implausible; in a perfect example of nominative determinism, one of the sparks of inspiration that led to the fan car was a letter written to the team by a young fan in “late 1967 or possibly early 1968, no-one can remember exactly” suggesting the use of—yes!—a fan.

If you’ve read Nick Skeen’s excellent John Barnard biography The Perfect Car, you’ll already know that its subject was even pricklier than usual about the credit—or lack thereof—given to him for the design of the Chaparral 2K. Texas Legend is, of course, “The Official Biography” of Jim Hall and I wondered how, or even if, this potentially choppy water would be navigated. To his credit, Levy doesn’t entirely duck the controversy and recounts Barnard’s displeasure on seeing the words “Jim Hall, Master of Ground Effect” on the Pennzoil billboard near the Indianapolis Speedway. Perhaps the words of the late HM Queen Elizabeth about her errant grandson Harry might be usefully recycled here . . . “Recollections may vary”?

This is a terrific book about a relatively unsung genius of motorsport and I recommend it without reservation. It’s beautifully written, superbly illustrated, and a credit to author and subject. Older readers like your reviewer will enjoy being transported back to their salad days, when news of Jim Hall’s latest innovation illuminated their Autosport almost weekly. And younger readers, especially here in the UK, will come to understand just how Anglo- and Euro-centric the domestic motorsport press (lower and upper case) has been in their GOAT selections. Because the Plymouth Road Runner might have had a cute Road Runner decal but the ur Road Runner came out of Midland Texas. Beep Beep!

The book has an extraordinarily good Index. A portion of the book sales proceeds will go to the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America whose president the author became in 2019. A Jim Hall-autographed bookplate is available from the publisher for $33 (the reason the book itself is not signed is that Hall is in the US and the publisher in the UK).

About the book:

Texas Legend: Jim Hall and his Chaparrals

“There’s Always a Better Way.” The Official Biography

by George D. Levy

Evro Publishing, 2024

8.5” wide, 10” tall, 1.25” thick

484 pages, 486 b/w & color images, hardcover

List Price: $80 ($52 on Amazon)

ISBN 13:978-1-910505-66-3

There are several post about Jim Hall on Dean’s Garage:

Jim Hall of Chaparral Cars—American Inventors Interview Series

Canadian American Challenge Cup—The CANAM (video)

The Way It Is—Appreciating Jim Hall and his Chaparrals

Ed Welburn’s Chaparral Experience

Jim Musser and Jim Hall—Collaborators in the Chaparrals

Chevrolet—Racing? Fourteen Years of Raucous Silence

1967 Spa 1000KM and the Chaparral 2F

Chaparral Exhibit at the Petroleum Museum, Midland, Texas

WOW! !!

What a fantastic review, I think the book got you pretty excited GARY. Unfortunately I was not able to go to Pasteiner and get a copy when the book signing happened. In the 1980s I met one of the two young engineers that were sent to Texas to work with Jim Hall when GM had to leave racing. His name was Mike Pocabello. After being a young engineer out of school and hiring in at CHEVROLET R&D, Mike was sent with all the racing information, parts and technologies to Texas. He had to quit his job at GM and worked there for three years. We would talk once in a while about different things that happened, Mike was a big proponent of four-wheel-drive. After the three years he came back to Chevrolet and then he and two others started their own company called Triad. That’s where I met him as we were doing a concept car there. As close as I I ever got to JIM Hall at that point in time. I was at Laguna Seca on a Friday night when the big truck rolled in, followed by a pick up. This really tall guy got out of the pick up, looked around at everything in the pits and said that he had never participated in vintage racing, but it looked like it might be interesting. a quarter mile away. While working in the CHEVROLET Studio, I recall hearing the big blocks running on a dyno at CHEVROLET a quarter mile away. It went on for hours. It had a strange pattern of screaming wide open throttle and then suddenly upshifting to unbelievable heights. It was unexplainable and then somebody told me. “Oh it’s got an automatic transmission”. Well that didn’t make sense.

Thanks, GARY. What a fantastic intro.

Growing up in the ‘60s and ‘70s was the best time with regards to cars, design and racing. So much creativity and ingenuity. Jim Hall embodied these attributes and inspired many of us. That’s why we hosted the Chaparrals at the EyesOn Design a couple of times. Most recently in 2022. Always a big hit to see them in person, even if they are only static displays.

Thanks for sharing !

GM Engineering Staff

I was a big fan of Jim Hall and the Chaparrals. Many good memories a Riverside International Race way.

Thanks for the review, Gary. It prompted an immediate visit to amazon.com to order a copy. Would be nice to meet Jim Hall at his HQ south of Midland, TX, but that’s unlkely.

Tempus fugit.

A side note: Author George D. Levy was the custodian, for a brief time, of the Datsun 510 “Brockbuster”, which still serves as THE benchmark for anyone wishing to restomod a 510.

Gary: You may know more about this as you were working for G.M. and may have spent time interacting with Frank Winchell, concerning his work with Jim Hall in the early Chaparral 2-A days. The first iteration of the Chaparral 2 briefly raced with a high nose resembling a snowplow. Later, the low nose with the high fenders may or may not have come from a collaboration between Hall and Winchell. But Hall was constantly experimenting with aerodynamics in a way that Carroll Shelby was not (at least with advancing chassis design). In April and May of 1965, editor David E. Davis and Jim Hall had a two-part article, “What Makes Cars Handle” in “Car & Driver”.

http://persh.org/images/Corvairs/WhatMakesCarsHandle01.pdf

http://www.persh.org/images/Corvairs/WhatMakesCarsHandle02.pdf

While I believe Jim Hall loved winning races until his horrific accident at the Stardust CanAm, he and Hap Sharp loved the intrigue of pushing the boundaries. Hall was hurt in several U.S.R.R.C. and CanAm races, but he was always experimenting with his chassis, Chevrolet engines, transmissions, spoilers and low/high pressure areas contained in body work. The account of Dave McDonald telling Carroll Shelby that the shifting noises emanating from Hall’s Chaparral 2-A were not normal for a manual transmission, where subsequently Shelby wrote an official letter to G.M.’s Fred Donner if he, Shelby, could purchase the Chaparral 2-A transmission or transaxle since G.M. was adhering to the manufacturer’s racing ban was hilarious.

I can see why Hall and Penske were attracted to each other’s racing activities. Most of the time, they both had impossibly high standards in the pits and in races. I think Penske was more driven to win after 1966, but Hall wanted to push the technology to win, whereas Penske fielded great equipment and had great drivers (especially with Donohue, Follmer, Mears and Unser), but not always the most innovative cars as long as they drove it into Victory Lane.

I’m always missing the Chaparral III Indy car or F5000. Does someone know if it will be restaurated and go to Midland museum?

I’ve previously posted about the intimate association between Chevrolet’s R&D Department and racing groups like Jim Hall’s Chaparral team, based on books like “Chevrolet: Racing?…” and Levy’s previous excellent account of the CanAm series on its 50th anniversary. But after buying Levy’s Hall biography, it’s now apparent that much of the engineering work advancing downforce and ground effects weren’t so much due to Chevy’s R&D as to Jim Hall’s amazing engineering prowess. His visions were largely supported by the essentially unlimited resources of GM and, along with Larry Shinoda’s Chaparral body designs (stemming from his 1962 Corvair GT body style), between them, they made huge advances in competition machines. Plus, Hall’s Chaparral was the test bed to work out bugs of the new Chevy aluminum big block competition engine. So a belated tip of the hat to the amazing talent to Jim Hall, thanks to Levy’s official biography.