Stylerama, Ford’s Aborted Answer to GM’s Motorama

By Jim and Cheryl Farrell

In 1949, GM invited the world to see the latest in automobile technology and the best of its new cars at auto shows in New York and Detroit. Those shows were successful beyond anyone’s wildest expectations, with more than 300,000 people accepting GM’s invitation. That extravaganza, renamed the Motorama, was repeated in 1950 and it drew more than 320,000 guests. After missing two years for the Korean Conflict, the Motorama returned in 1953. In addition to New York City, the 1953 motorama traveled to Miami, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Dallas and Kansas City. Ford executives who attended the ‘53 Motorama were impressed with the public’s response to GM’s concept cars and they couldn’t help but notice that 1.5 million people joined them as guests of GM. By 1956, the Motorama shows, displays and concept cars were even more spectacular, and attendance rose to 2,348,241 people. Ford was trying to close in on industry sales leader Chevrolet by competing head-to-head in everything—and that meant that Ford started looking for an answer to GM’s Motorama.

Ford’s answer came from John Cuccio. Before he was hired as a Ford designer, Cuccio spent 15 years as a designer for Raymond Loewy and Associates, where he learned something about showmanship. After Loewy lost the Studebaker account, Cuccio was assigned to design and supervise the building of a Loewy show car for the 1955 Paris Auto Show. While he was in Turin, Italy, supervising the building of the car, he received a telegram from Frank Hershey offering him a job as a designer at Ford and he was asked to come to Dearborn to meet with Hershey. When Cuccio returned to the US, he called the Ford Design Department to make an appointment, only to find out that Hershey was no longer at Ford and that George Walker was the new boss. Walker didn’t know anything about the telegram but agreed to meet with Cuccio and then hired him as a manager in Buzz Grisinger’s Mercury pre-production studio.

After Cuccio settled in, he suggested that Ford design and build a dozen or so full-sized futuristic showcars, put them in specially-designed trailers and truck them across the United States and Canada. Like the one used to display the XM-Turnpike Cruiser, Cuccio suggested that each trailer be designed with sides that opened and with attached decks and awnings. Cuccio gave Walker several renderings that showed the trailers drawn up in a circle, covered wagon style, with people around them looking at Ford’s futuristic cars. Walker loved the idea, named it the Stylerama and recommended it to Henry Ford II as Ford’s answer to GM’s Motoramas. As soon as he heard the proposal, Henry Ford II became as enthusiastic about it as Walker. He asked for cost estimates, and ordered that the plan be implemented as soon as possible.

Walker asked designer Bob Maguire to organize the program. In March 1956, Maguire stepped down as head of the Ford studio to organize a new Advanced Studio. Al Mueller was assigned to work with Maguire. Buzz Grisinger was also reassigned from the Mercury pre-production studio to Maguire’s studio to help with the Stylerama program. Instead of having two advanced studios, Alex Tremulis’ studio was done away with and he and Bill Balla, a designer in Tremulis’ studio, were assigned to Maguire’s new Advanced Studio to help with the Stylerama cars.

The first thing Maguire did was to ask Tremulis and Balla to design several advanced cars. Maguire also asked that the other studios each come up with designs for two futuristic cars for a special show to be held in the Design Rotunda. To encourage the designers’ undivided attention to the task at hand, Maguire was given a small room downstairs in the Styling Center where designers selected from each studio were temporarily reassigned until their Stylerama proposals were finished.

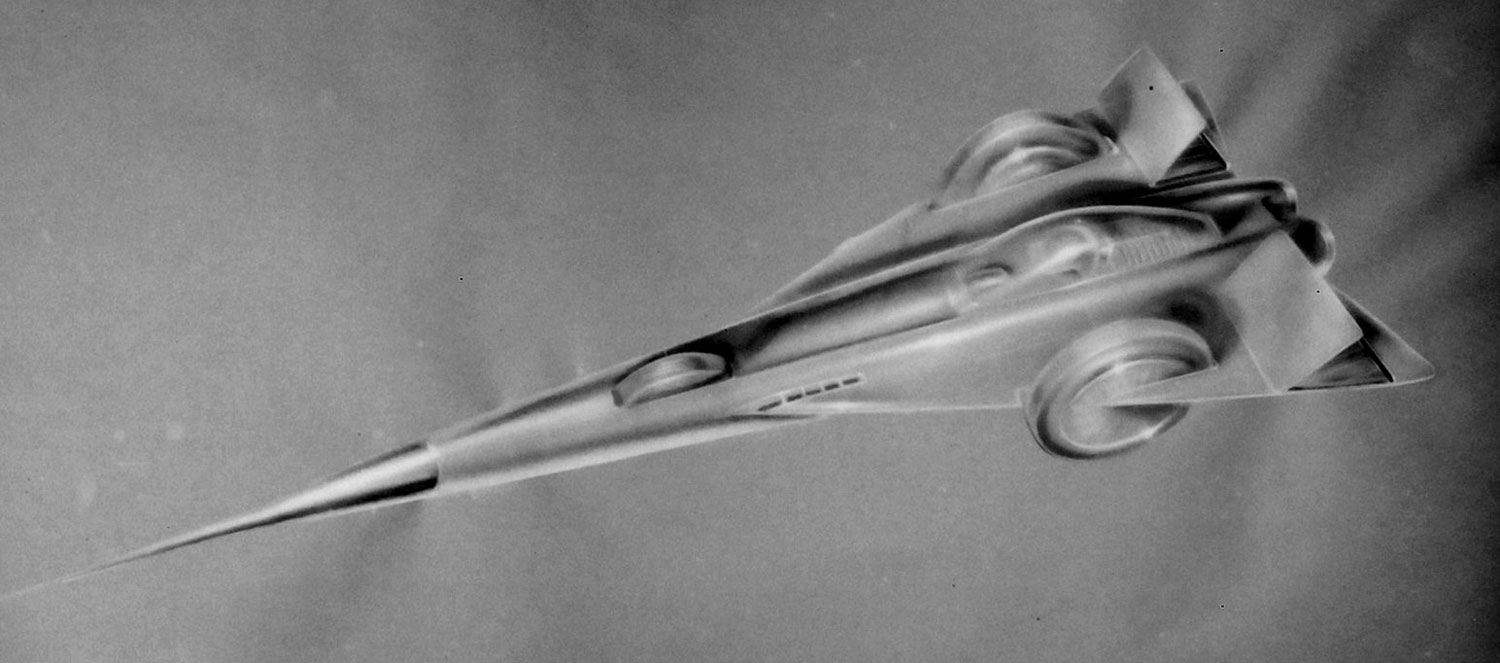

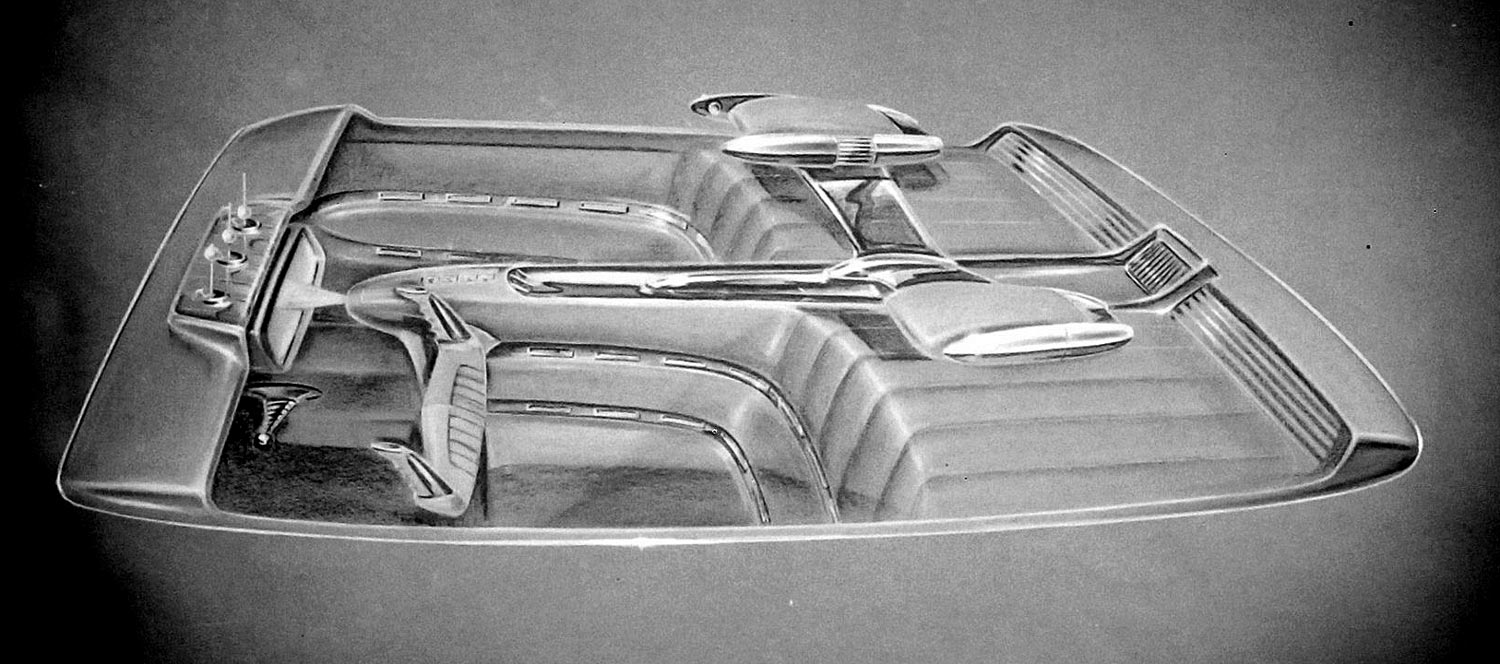

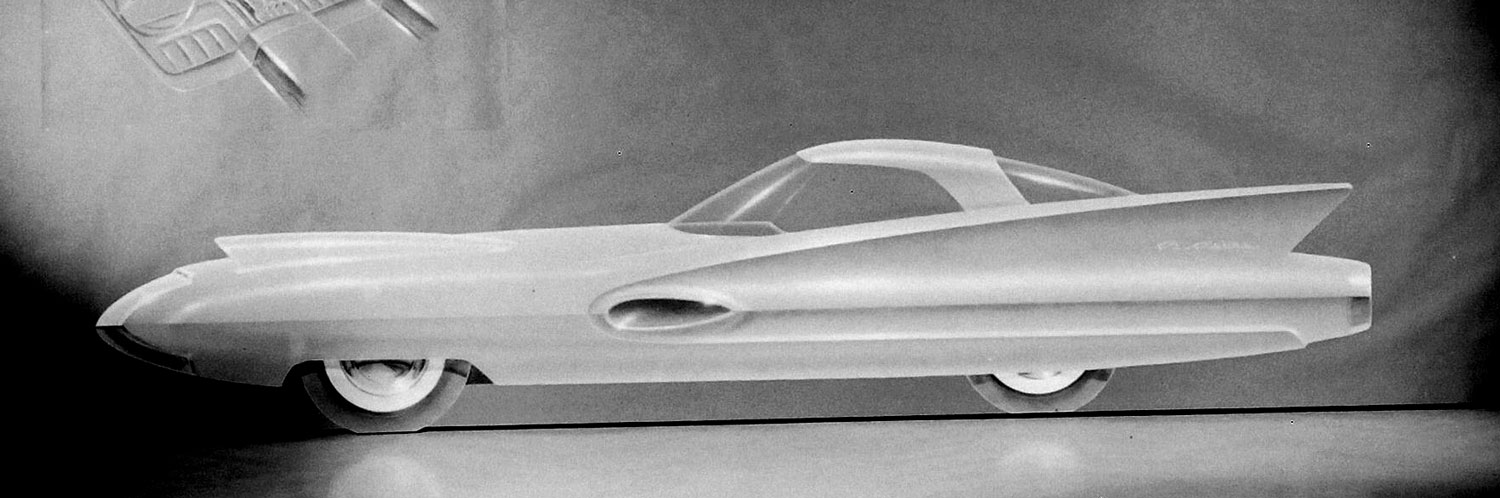

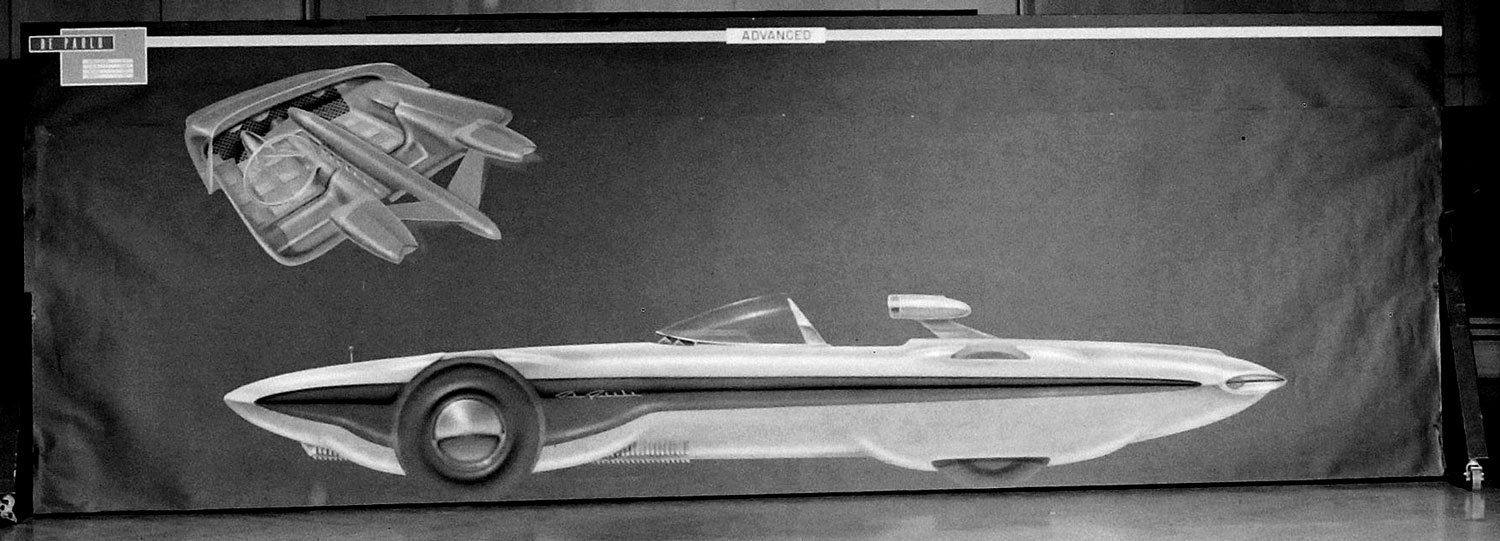

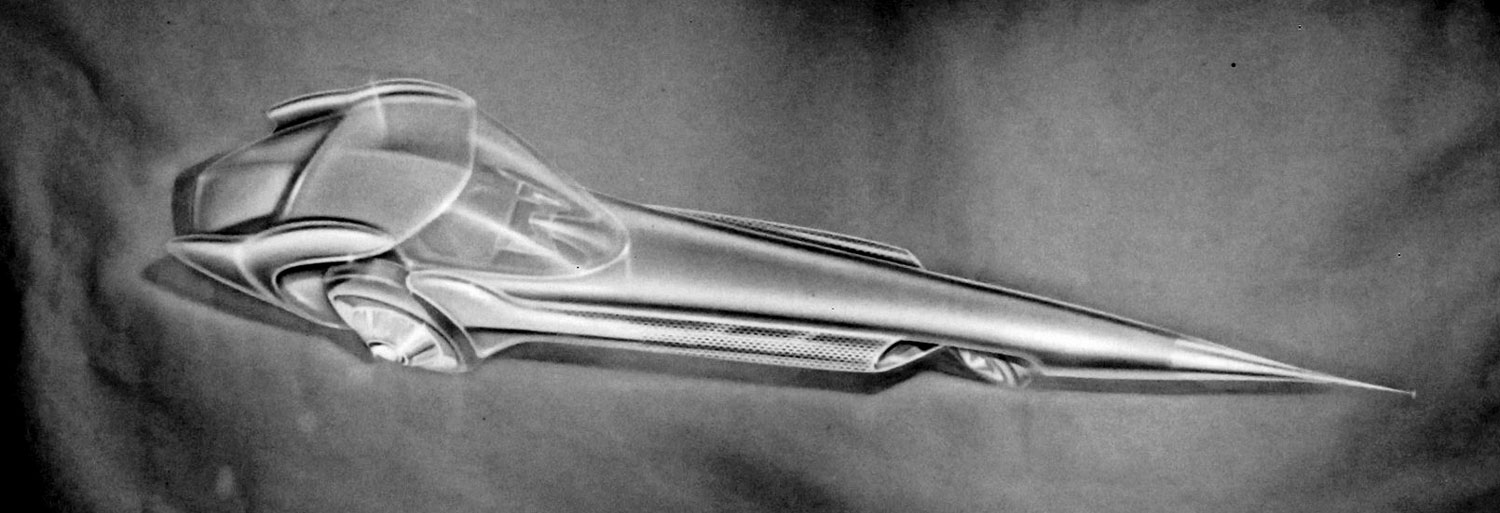

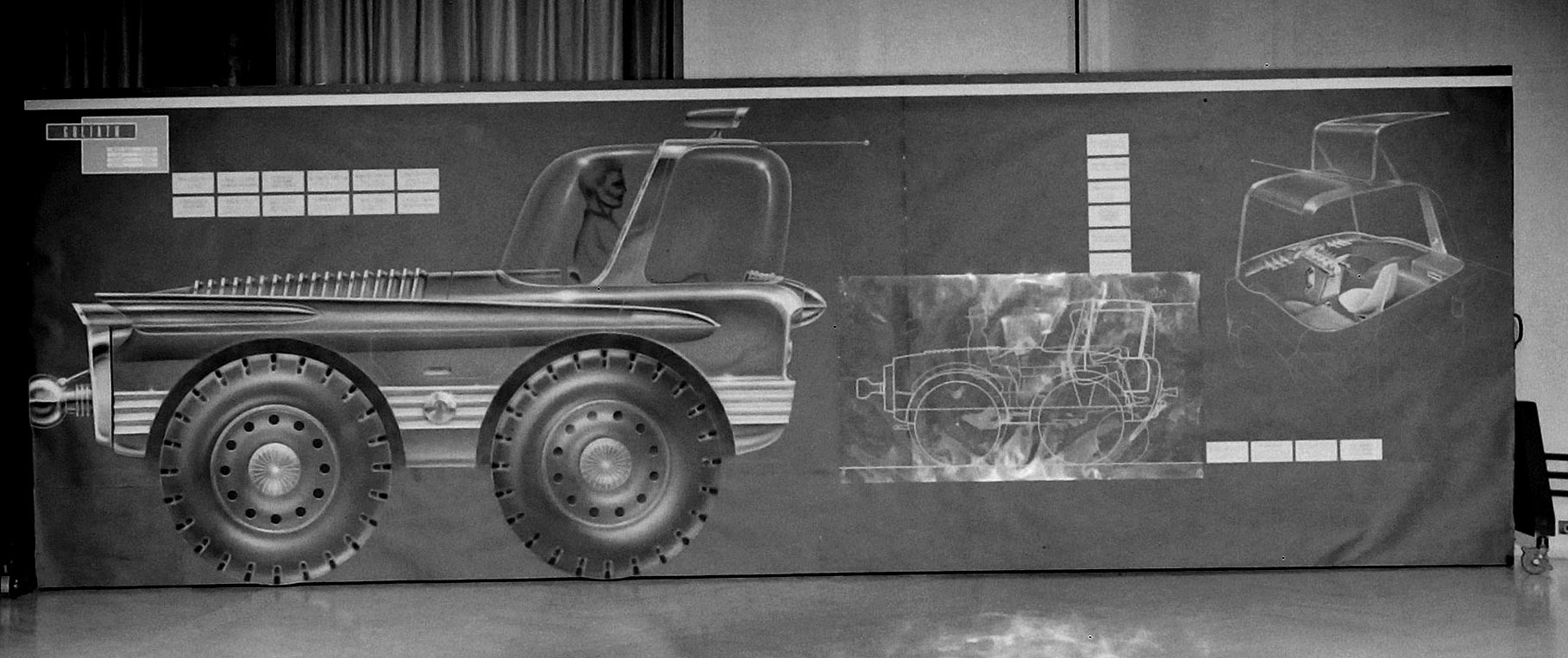

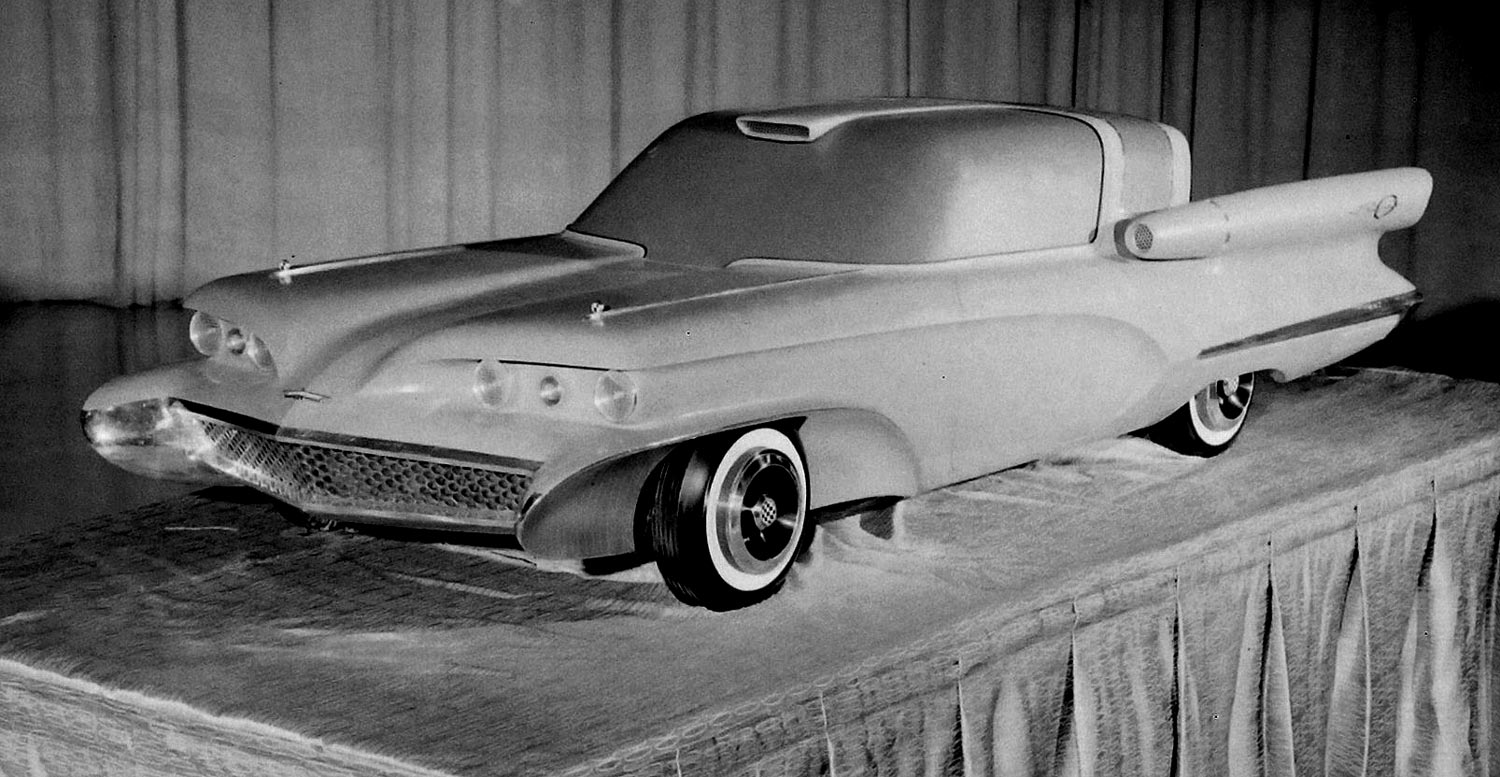

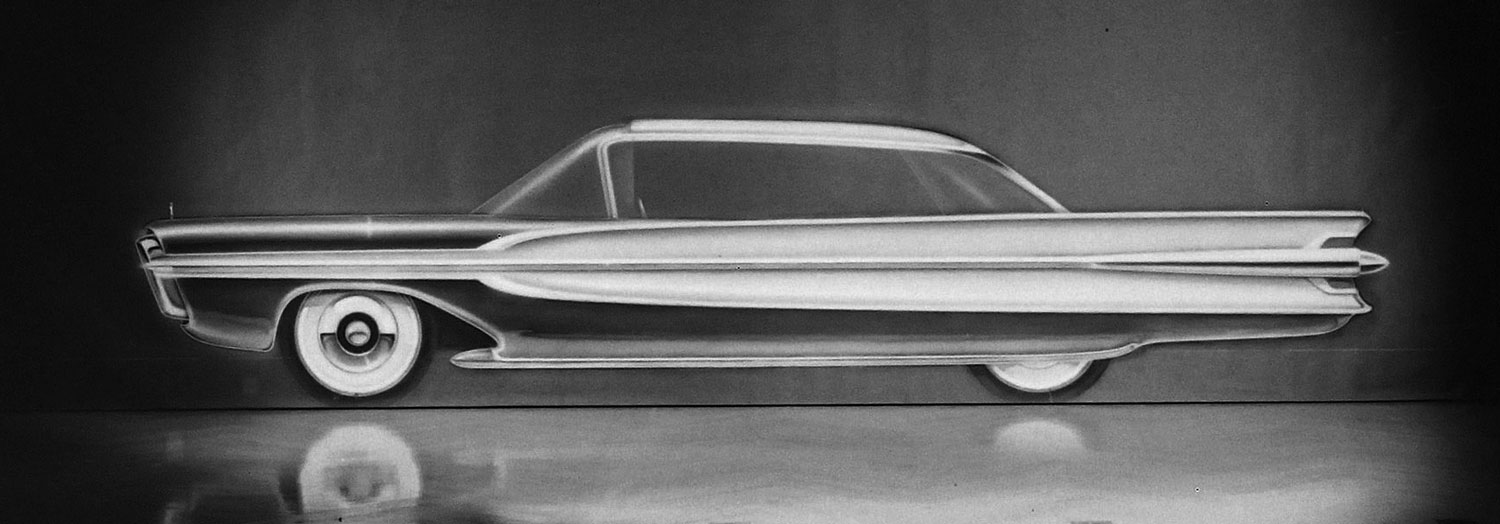

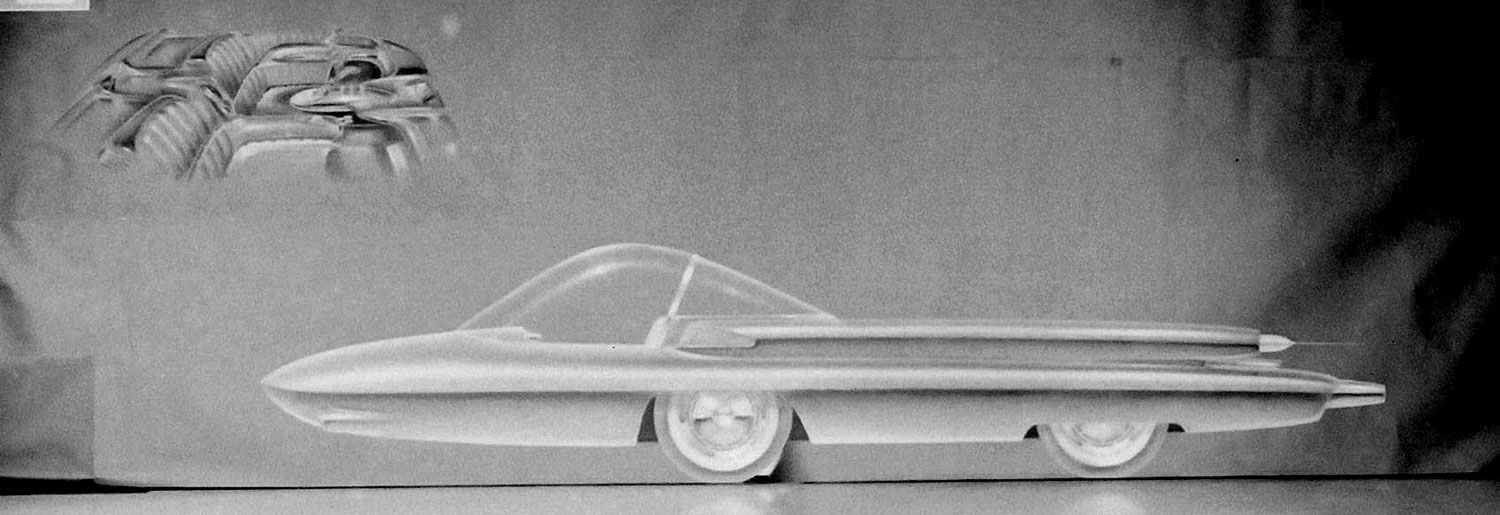

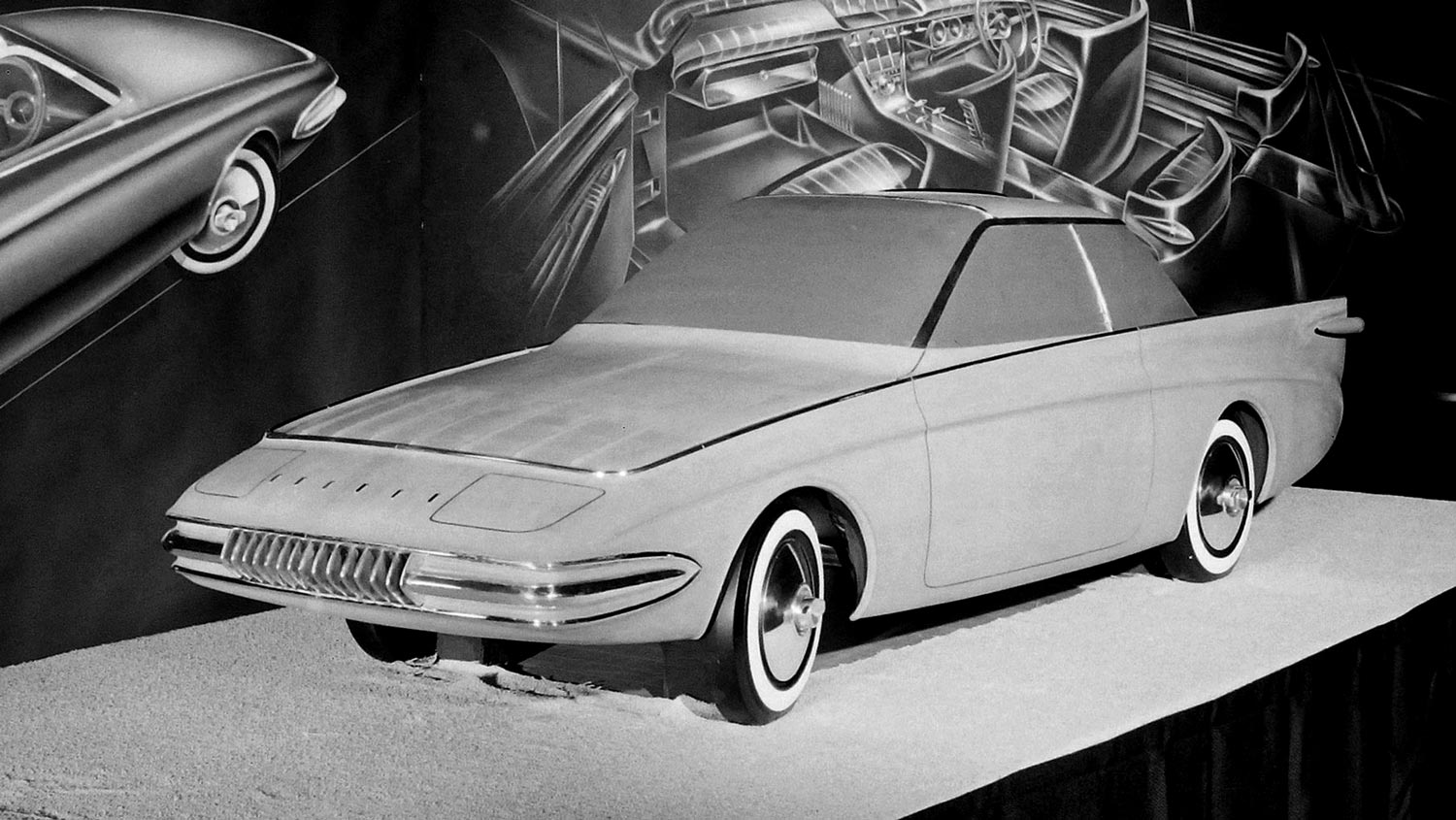

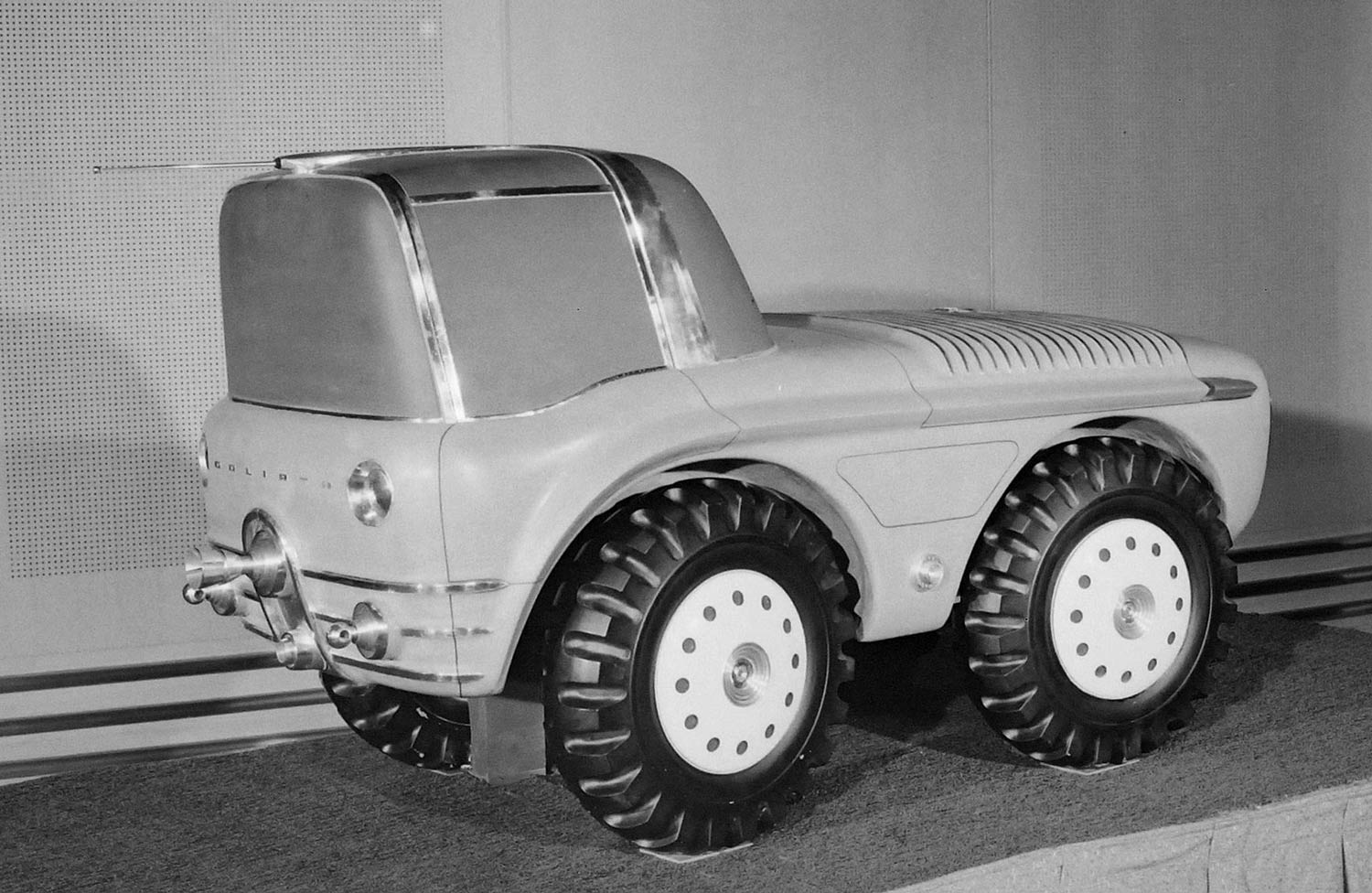

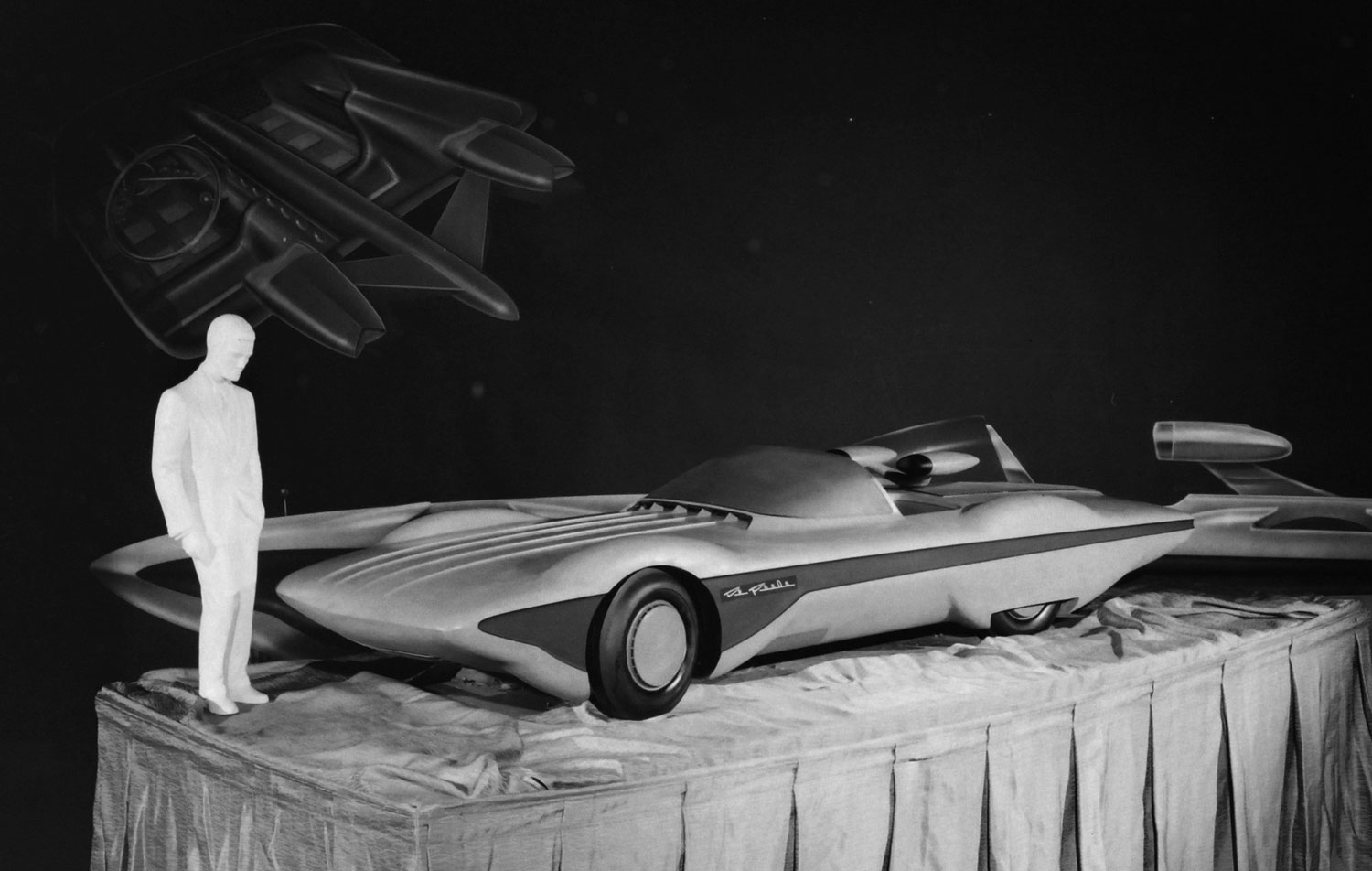

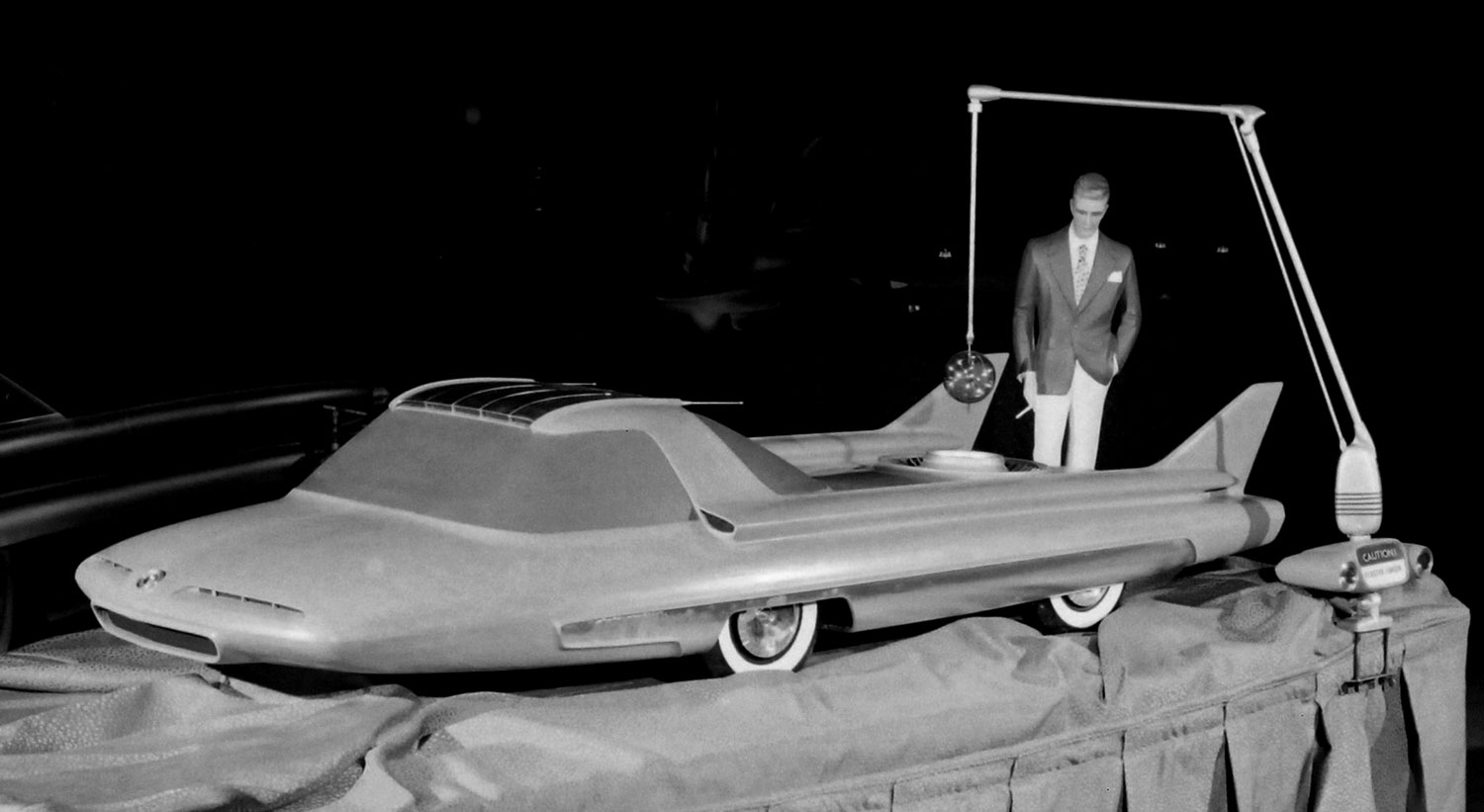

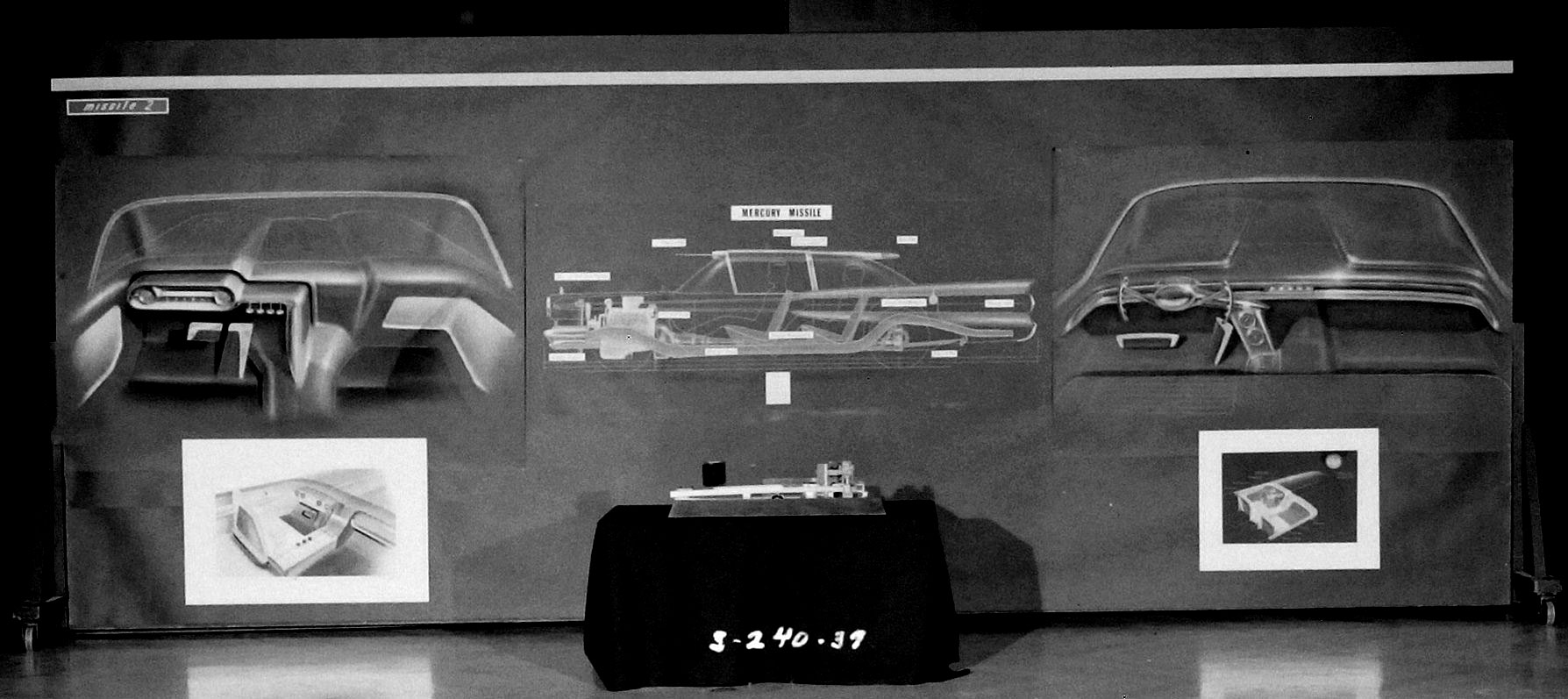

On April 3, 1956, a special show was held in the Design Rotunda to pick the cars to be built for the Stylerama program. Fourteen 3/8-sized models were chosen from the 22 designs submitted. Because the XM-Turnpike Cruiser had been built by Ghia from a 3/8-sized model, the plan was to send the selected 3/8-sized models to European coach builders, who would then build the full-sized Stylerama cars.

John Cuccio and Walker’s administrative manager, V. Z. Brink, left on April 27, 1956, to visit coach builders in Italy and Germany. Their purpose was to evaluate facilities, get price and time estimates and assess security at each facility. The Mercury XM-Turnpike Cruiser, which had recently been built by Ghia, was used as the benchmark for cost, time and needed supervision.

During the two weeks they were gone, Cuccio and Brink visited Ghia, Vignale, Boano, Bettone, Farina, and Touring in Italy, and Spahn and Dranz in Germany. On May 14, 1956, Cuccio and Brink returned to Dearborn. They submitted a ten-page report to Walker and Maguire. Cost estimates they received ranged from $15,000 to $45,000 for completed full-sized pushmobiles, and it was estimated that it would take four to six months to build each car.

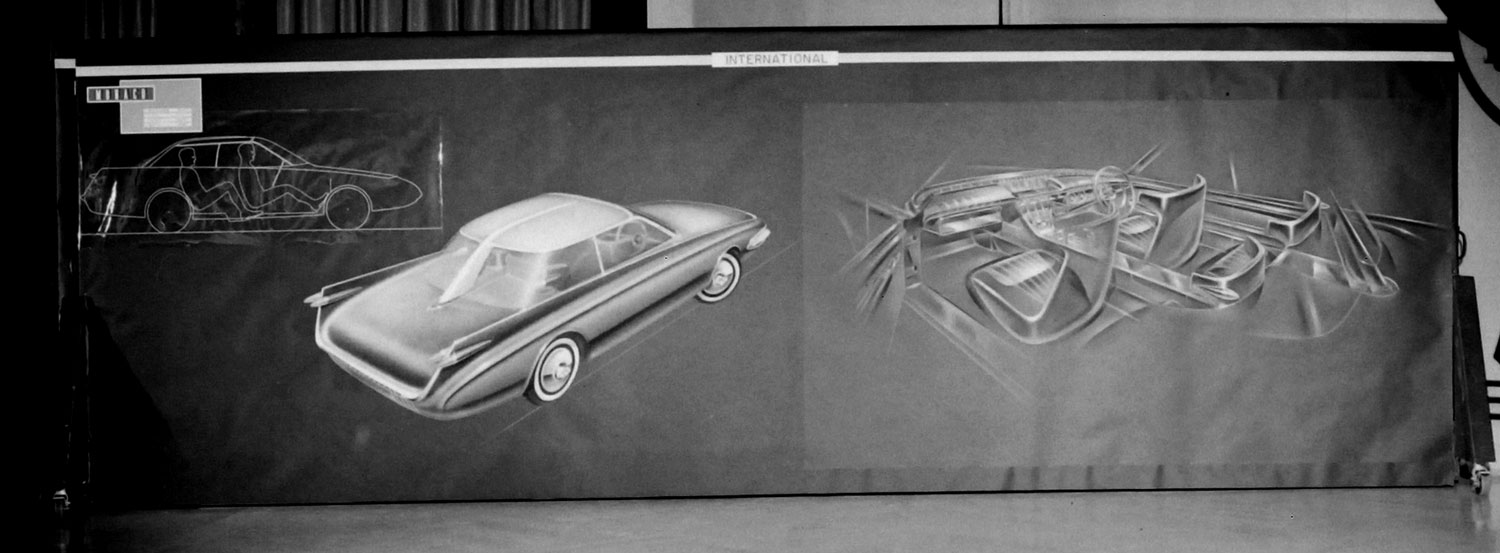

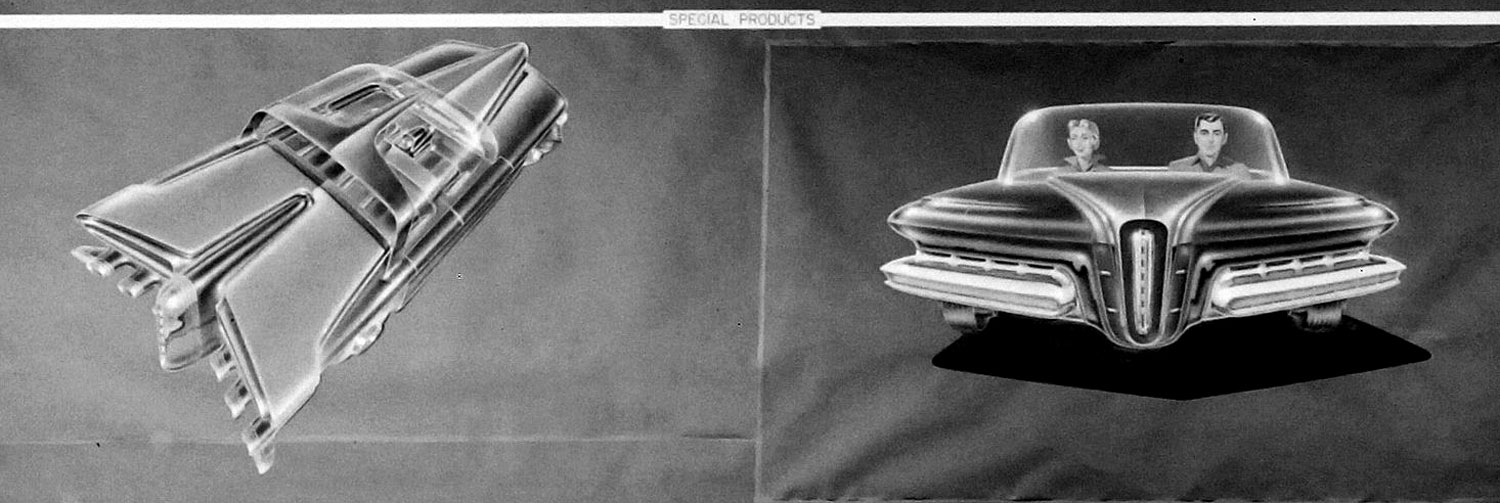

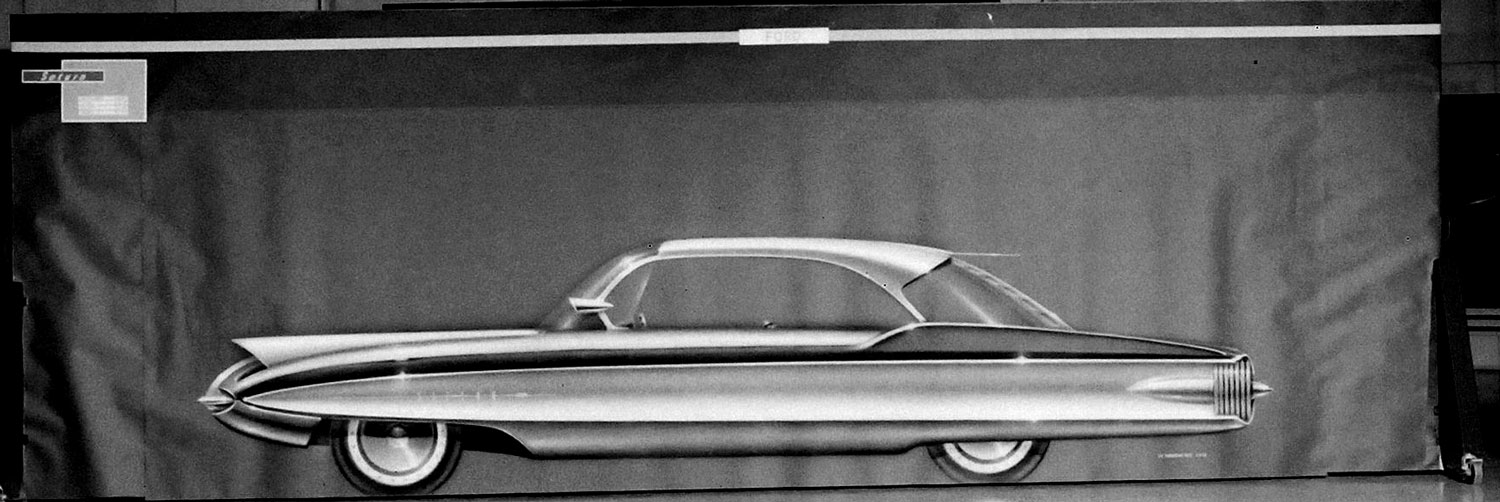

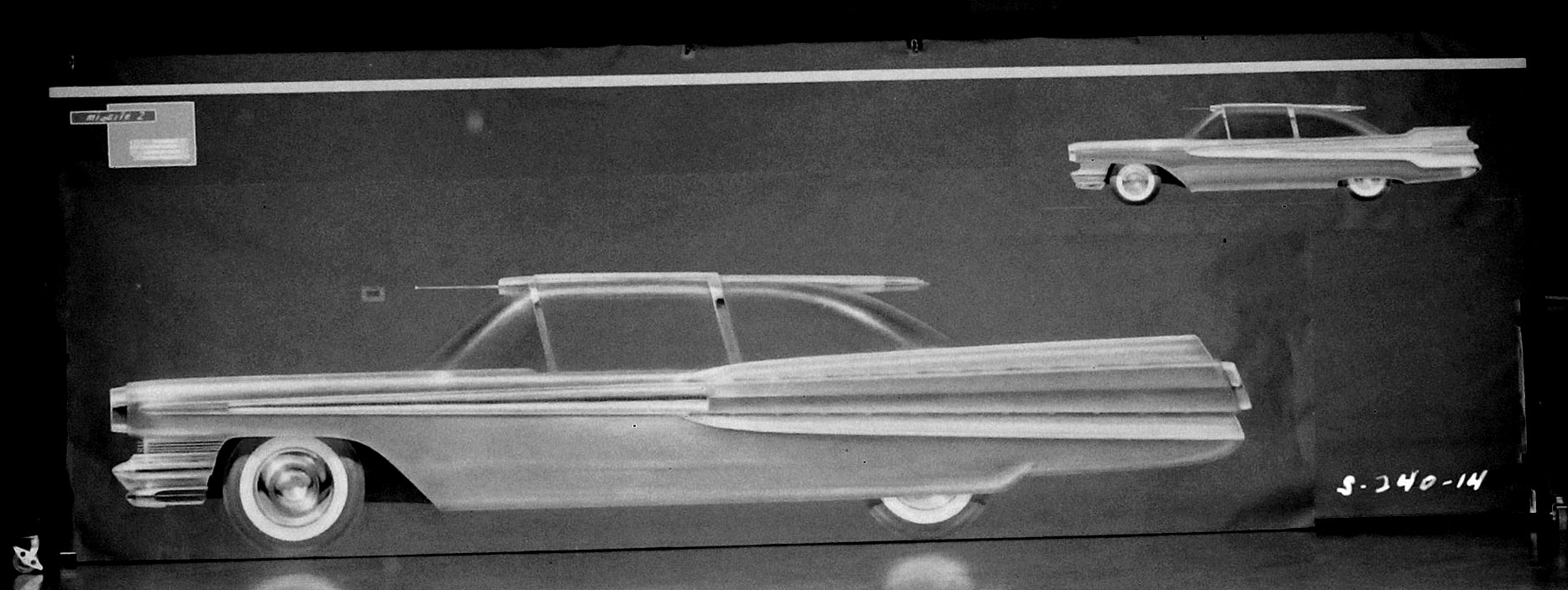

Ford Motor Co. decided to ask each Italian coach builder to build two or three inoperable cars—all they had to do was look real. The next step was to negotiate a fixed price, sign contracts, and then send the 3/8-sized models, full sized side-view renderings, and the needed hardware to Italy. Mario Boano was negotiating with Fiat to become head of their Advanced Studio, but he told Ford he would maintain his separate coach-building business if his firm was awarded a contract to build the show cars. The accompanying photographs are of the fourteen 3/8-sized models selected and the full-sized side-view renderings it was planned to send to the Italian coach builders selected to build the full-sized cars.

Instead of shuttling someone between Dearborn to Italy to supervise construction, it was proposed that Cuccio, who had grown up in Sicily and spoke fluent Italian, move to Turin, where he would personally supervise the construction of the Stylerama cars. Cuccio found an apartment in Turin, and he and his family arranged to relocate there. Ford agreed to furnish Cuccio with a new Thunderbird and a new Ranch Wagon each year he was in Italy, and he had already ordered cars for his first year.

After the full-sized Stylerama cars were finished and delivered to Dearborn, plans were to put two in each trailer, and send five of the trailers across the United States, while two cars and one trailer were to tour Canada. The Stylerama displays were to be set up on vacant lots, in stadiums, or any other places where the public could see the cars and the accompanying entertainment Ford planned to accompany the cars.

Starting with the XM-Turnpike Cruiser, Ford concept cars generally bypassed dealers, who had come to feel that concept cars displayed at their dealerships tended to discourage rather than encourage prospective buyers. Dealers apparently felt that the features on Ford’s concept cars only encouraged the buying public to wait until those features were available on the cars they were selling.

The departure date for the first Stylerama caravan was planned for early 1957, but it never happened. Although the program was an open secret at the Styling Center, no public announcement was ever made.

Many assume the Stylerama program was canceled because of the Edsel disaster, but the answer is much more complicated than that. Although some executives at Ford had premonitions of the financial disaster that was about to befall the Edsel with losses exceeding $250 million, the Stylerama program was canceled because cost estimates for everything but the cars were too high. Some of the cars were also judged as a little too far out to be shown in middle America. As Joe Oros recalled, the program collapsed of its own weight and, by the time the Edsel was introduced, it was too late. Cancellation of the Stylerama program was a great disappointment to John Cuccio, who soon left Ford to open his own industrial design firm.

Although some of the 3/8-sized models from the aborted Stylerama program were designed and made before the program started, and some were later shown as Ford show cars. Today, no one remembers Ford’s planned answer to GM’s Motorama. We can only imagine what the public’s reaction to Ford’s Stylerama would have been.

Perhaps it was a good thing that the Stylerama was cancelled. It might have proven to be an embarrassment for Ford.—Gary

Photos: Ford Design

Books by Jim and Cheryl Farrell

Ford Design Department—

Concepts & Showcars

1999, 10×13, 400 pages, Fully indexed

900 photos. Includes 150+ designers and sculptors, and highlights 100 concept cars.

ISBN 0-9672428-0-0

Lincoln Design Heritage:

Zephyr to LS (1936-2000)

2021, 10×13, 480 Pages, Fully Indexed

1,600 photos and illustrations

ISBN 978-0-9672428-1-1

The Ford book is $50 plus $7 S&H (US). The Lincoln book is $85 plus $10 S&H (US). Both books bought together are $110 plus $17 S&H (US). To order, email: cfarrell57@gmail.com

With the exception of Firebirds I and III, GM Motorama cars looked buildable Not so most of these proposals. In view of the excellence of several production Ford cars, perhaps it’s better these remained in the studio drawer.

A great article about a time the likes of which will never be seen again. Using the draftsman’s desk lamp as a “refueling” arm for the Nucleon (3rd pic from the bottom) is an inspired piece of whimsy.

The problem I have with all this wonderful information is that I had never heard of it. As someone from a four-generation car guy family that just goes to illuminate another Ford failure in that era….and even now it persists. What’s the Ford equivalent to “put an LS into it!”? There isn’t one. Where’s Ford’s equivalent to the Chevrolet 265 ci V8? There isn’t one. So it doesn’t really shock me that I never saw any of this before. I’d still love to see a set of articles on Ford’s turbine power experiments – you know, the ones they didn’t publicize nearly as well as Chrysler?

…sorry, this got cut…as for some of the vehicles being too “far out”, jeepers guys, GM was showcasing the Firebirds! You know, the ones that look like (1) a rocket ship on wheels (2) a bubble-top sedan from a science fiction movie and my favorite (3) a cross between a spaceship and a coelacanth. Too far out? Wow.

The difference was that the GM Motorama cars for the most part looked great! They could because, as was pointed out, they weren’t being shown in dealerships, where they would indeed have encouraged buyers to wait.

These are largely embarrassing except for 028, which had the makings of a classy sporting car.

Another great story!

Agree about 028, but 029 might be a forecast of some ‘things’ we see today. A few had GM-ish features and one wonders if the designers went to GM after the plan was scrapped.

Amazing.

It appears that there was a lot more thought behind the GM Motorama cars.

The designs were within reach and offered a lot of design fuel for the future. A lot of the design content inspired solutions for the near future that set each divisioin on a clear and non-conflicting image track.

This was very hard to do compared to just doing wild cars. The Firebirds were clearly dreams and the Motorama cars were the future.

Ford in many ways was inspired by GM yet their understanding of what they were doing was very two dimensional. Amazing that it took almost six years to respond to the Motorama effort. GM benefitted greatly as the task of quickly designing the Motorama cars evolved their design processes and also developed their design skills. It would take years for Ford and the rest of the world to catch up. They also had a steady and skillful manager in Harley Earl who had a good vision of the future.

By giving each division their own design identity Earl would ultimately show the corporation how he could create common bodies with unique fronts and rears. That is how he was able to capture design control for all five divisions.

Earl was also able to refine his own design skills and improve his staff. It appears that he was a very clever guy.