Snyder’s 1949 Continental

By Jim and Cheryl Farrell

George Barbaz enlisted in the U.S. Army during his senior year in high school. After a short boot camp he was designated an infantryman and sent to Italy. By 1946, the war over, Barbaz who had recovered after being twice wounded, received an honorable discharge, and returned to his home town of Dearborn, Michigan. Barbaz wanted to be a car designer, so he enrolled at Meinzinger’s Art Academy. Like many other veterans attending school on the G.I. bill, he got a part-time job at a local gas station. One of his regular customers was Jake Aldrich, a Ford designer. Aldrich also drove exotic European cars and that impressed Barbaz. When Aldrich found out Barbaz was an art student, and wanted to be a car designer, Aldrich suggested he apply at Ford when he finished schooling. In January 1948, a week before he finished school, Barbaz got an appointment with George Snyder, the new head of the Ford Design Department. Snyder took one look at Barbaz’ portfolio, showed it to a few others, and hired him on the spot.

Snyder had previously worked in GM’s Oldsmobile design studio. Before that, he had worked on Harley Earl’s Buick Y-job, and had risen to become the Oldsmobile’s studio head, but quit in early 1947 because he felt Earl had unfairly passed him over for promotion. Snyder was hired by Ford in August 1947, with a promise he would soon become head of Ford’s Design Department. One of Snyder’s first projects, when he got to Ford, was to ask for a separate advanced studio staffed with hand-picked designers to design his idea for the ’49 Continental. Although he didn’t explicitly say so, Barbaz suspected he was hired by Snyder to work on his new Continental proposal.

After the war almost every designer at Ford was trying to design the new Continental. Snyder and every other Ford designer assumed there would be a new Continental in 1949, but when Snyder was hired an acceptable design had not materialized. All Ford designers, including Snyder, wanted to be known as the designer of the new Continental. Barbaz’s first assignment was in Gil Spear’s Advanced studio, but after only a few weeks there, Snyder reassigned him to the new advanced studio he had just set up to design and clay model his idea for the 1949 Continental.

In addition to Barbaz, designers assigned to Snyder’s special studio included Bob Thomas, Gene Bordinat, Bob Maguire and Don Beyreis, all young designers who had also jumped ship at GM to take jobs at Ford Design. Another transplant from GM, Charlie Stobar, became the lead clay modeler on Snyder’s proposed ’49 Continental.

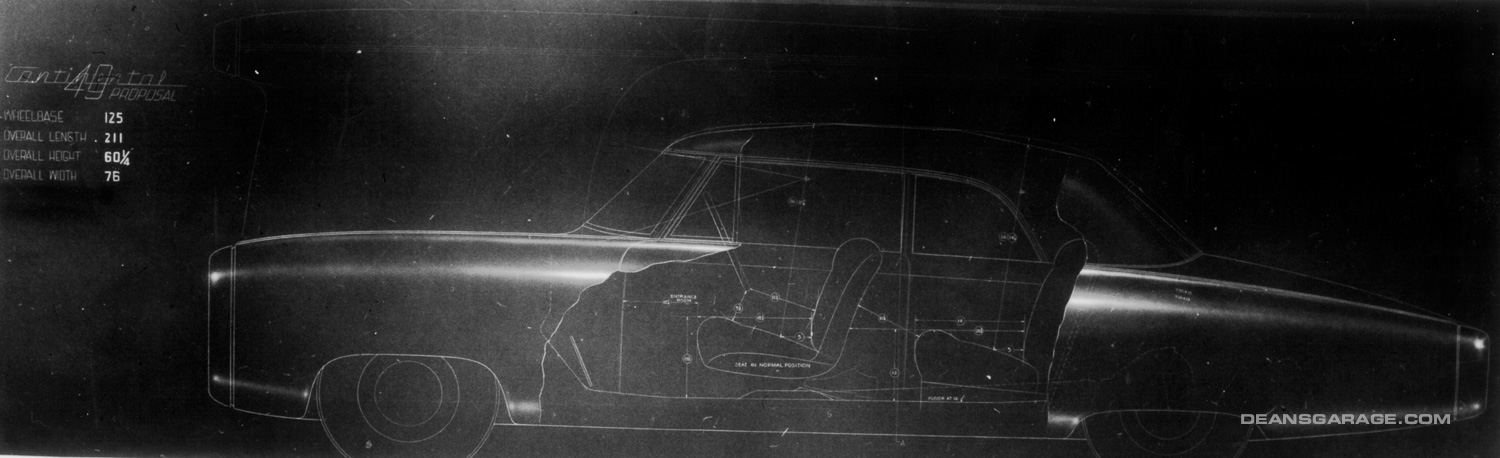

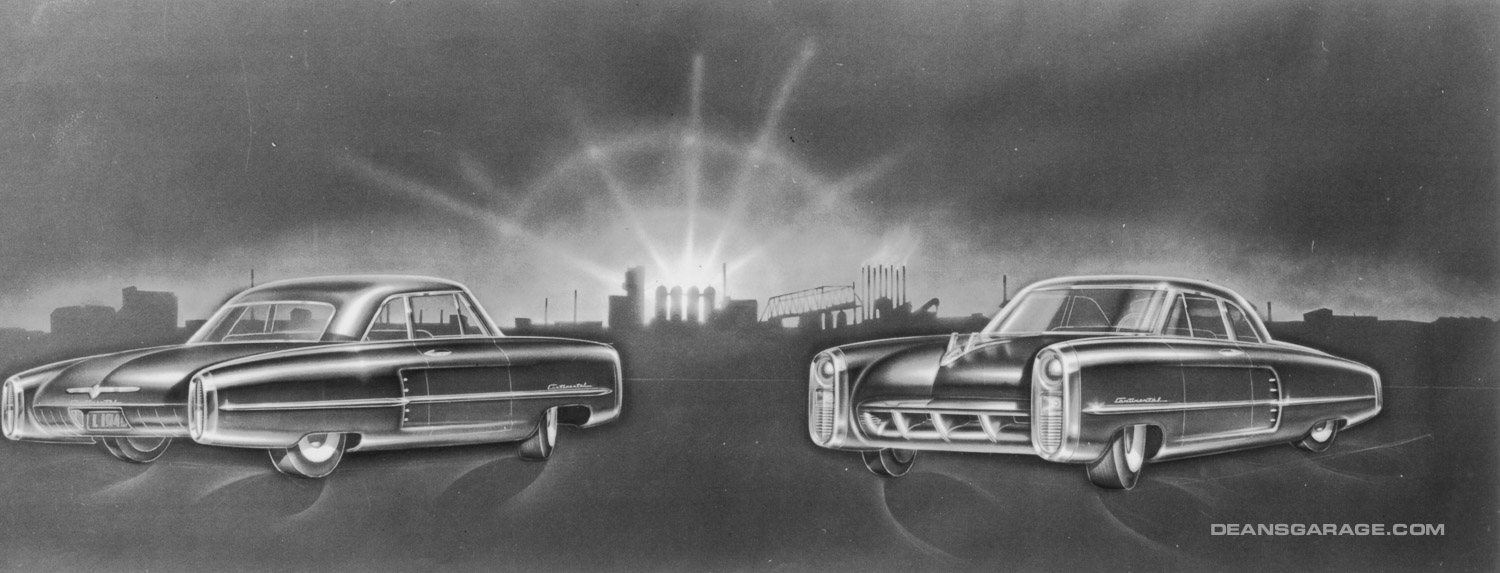

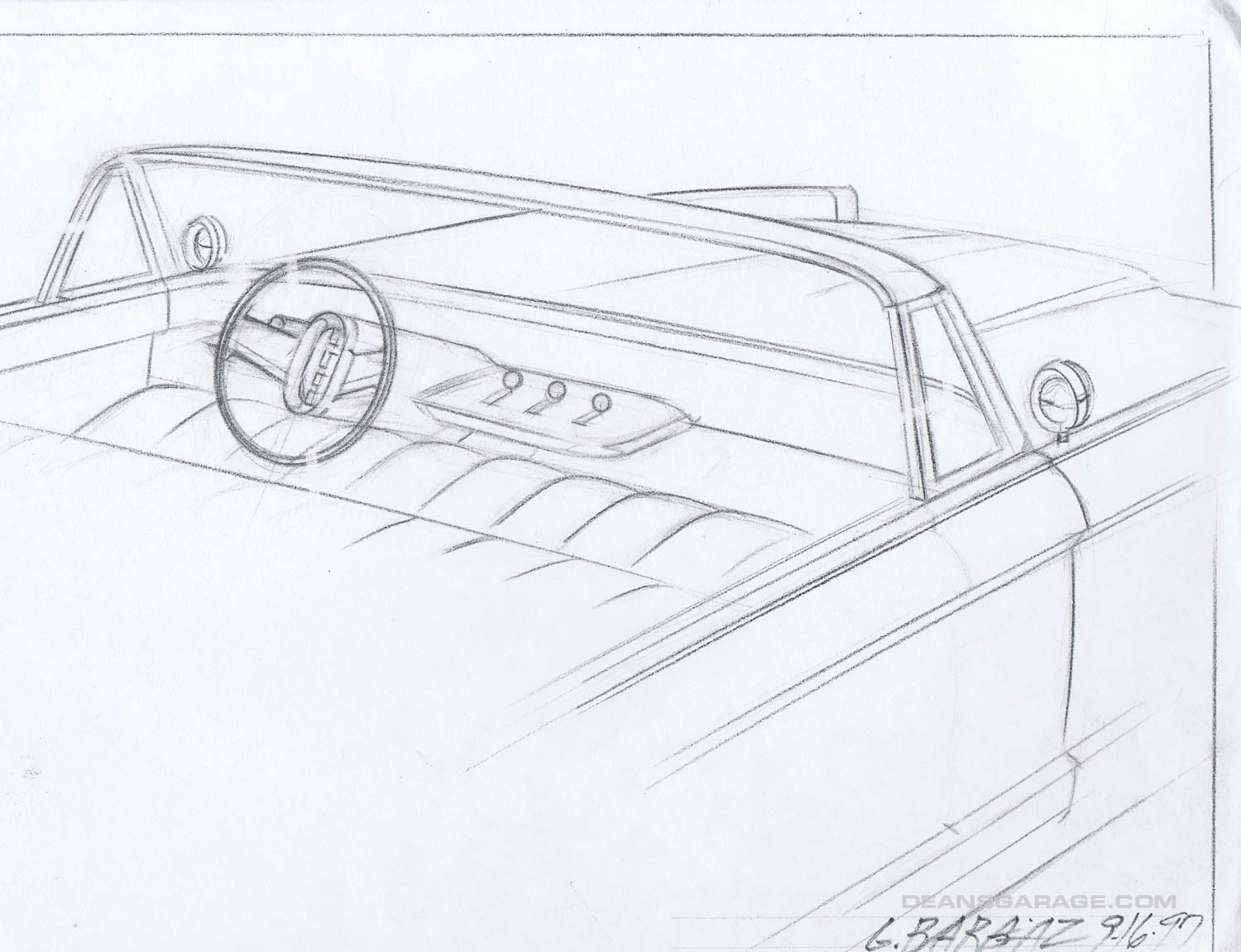

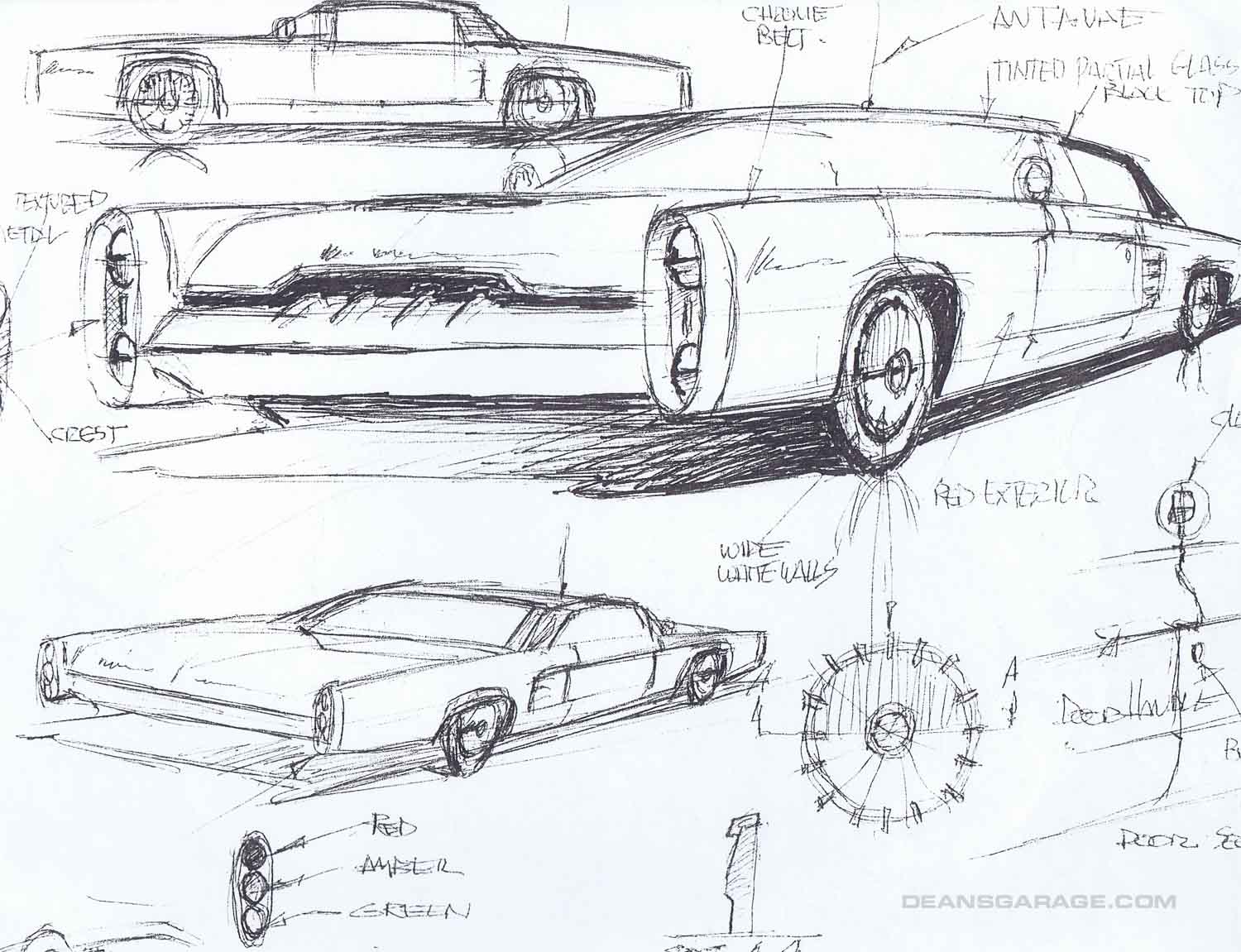

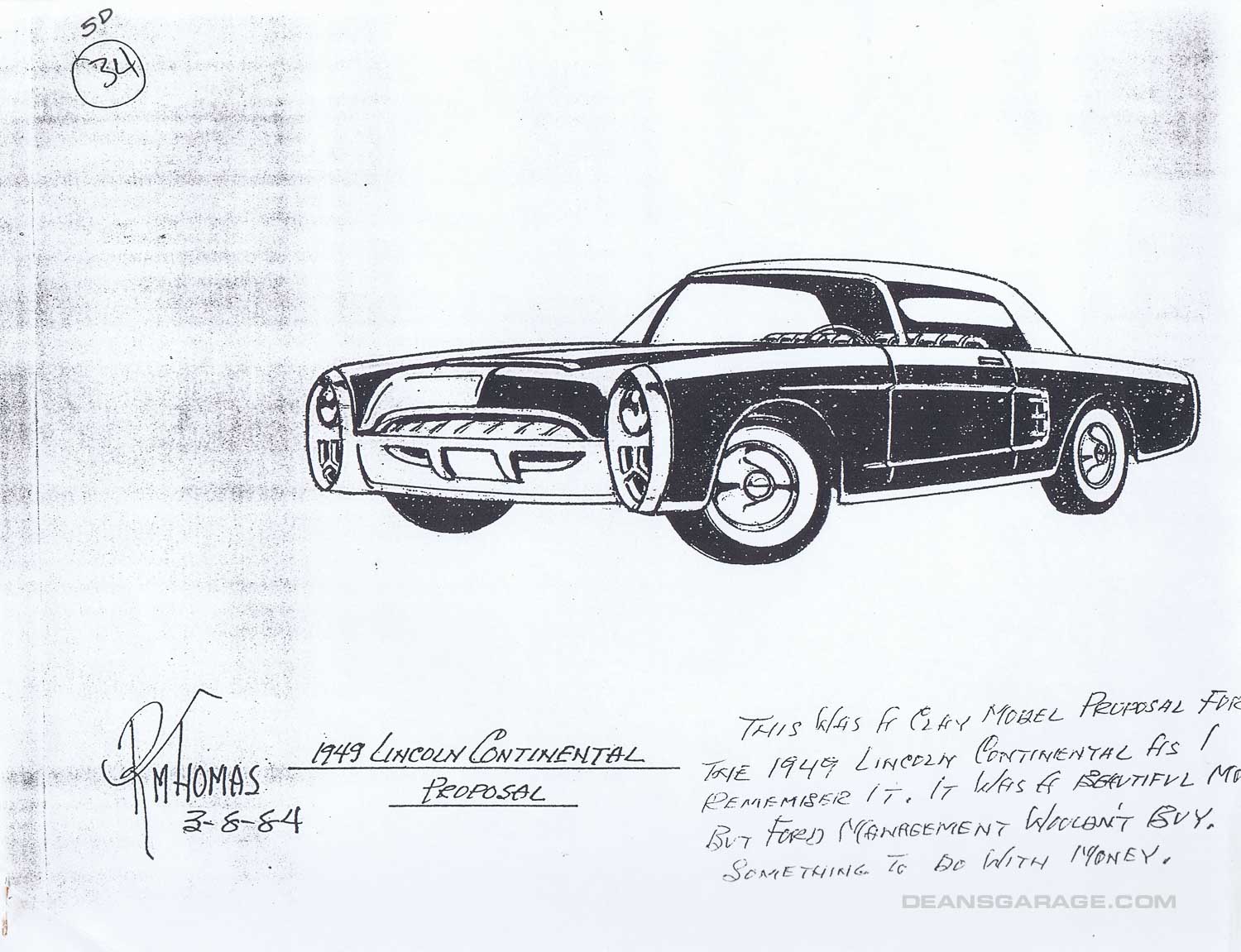

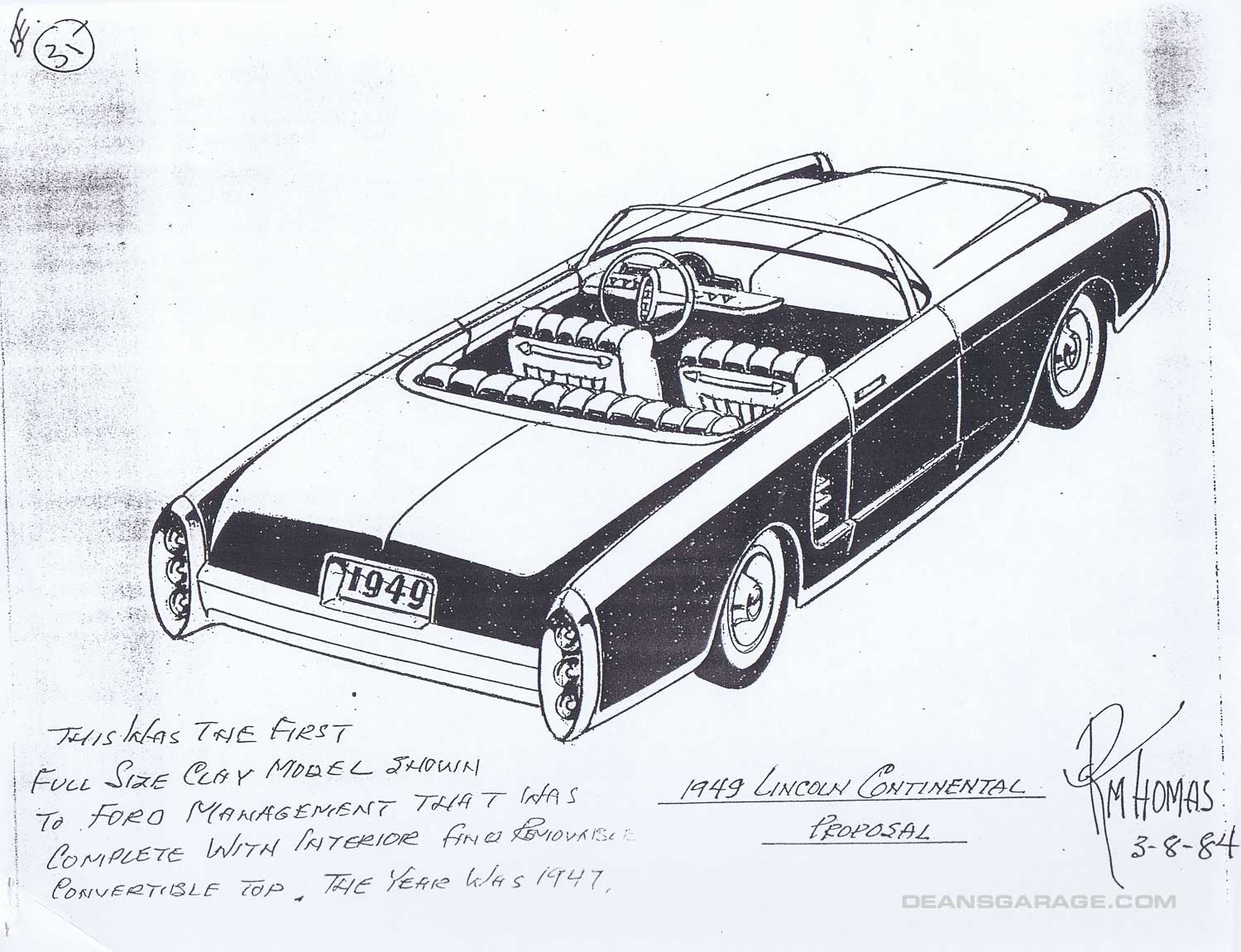

Snyder’s ’49 Continental proposal started out with Thomas making full-sized side-view drawings of the car on large blackboards. The plans Thomas followed were given him by Snyder, and the only change Thomas made from Snyder’s plans was to adjust the dimensions of the car to those of the Continental. While that was underway, a special armature was made in the Ford shops so Snyder’s ’49 Continental could be clay modeled with a full interior. With directions from Snyder, Bordinat and Barbaz completed the exterior design, while Maguire designed the interior, except for the instrument panel which was designed by Beyreis. When the car was finished, Snyder’s ’49 Continental was painted bright red, and the dash knobs and exterior bright metal pieces (door handles, mirrors, wheel covers, etc.) were all cast in metal and plated. The interior of the car was fully upholstered, and a separate removable hardtop was made for it.

Snyder’s 49 Continental was so advanced looking, Ford management didn’t think the public was ready for it, but everyone who saw it agreed it was beautiful. In fact, Snyder’s proposed ’49 Continental looked so real, during a review by upper management, executive vice president Ernie Breech tried to open the door by pulling on the door handle. Snyder’s ’49 Continental proposal cemented his appointment as head of the Ford Design Department, which came in August 1948.

Then something happened no one expected. Harley Earl, director of GM’s Art and Colour Section, called an executive at Ford. Earl gave the Ford person he talked to a detailed description of Snyder’s ’49 Continental proposal, and said that Snyder had designed the exact same car at GM—and had taken the plans from GM when he left. Earl also told the person on the Ford end of the conversation that he had the original plans and photographs of the car at GM to back up what he said. Earl finished the one-sided conversation by saying that if Ford built that car, GM would sue! Soon after the conversation ended, Snyder’s proposed ’49 Continental disappeared together with—so everyone thought —all photographs and sketches of the car. Snyder was soon terminated from his job at the Ford Design Department, supposedly for an unrelated reason.

According to long-time Ford designers, even without photos of the clay model, Snyder’s proposed ’49 Continental had a profound influence on the future Fords, Lincolns, and Mercurys they designed, including the side scoops and vents on the sides of the ’65 Mustang, the windshield shape used on the X-100 and 1955–57 Thunderbirds, the tail light housing, rear bumpers and instrument panel of 1952–54 Mercurys, the pushbutton-shift quadrant in the XL-500 and ’58 Edsel steering wheels, the ’61 Thunderbird’s “hidden” door handles, and the high stainless beltline of the Quicksilver, 1960 Ford, ’61 Thunderbird and the ’61 Continental.

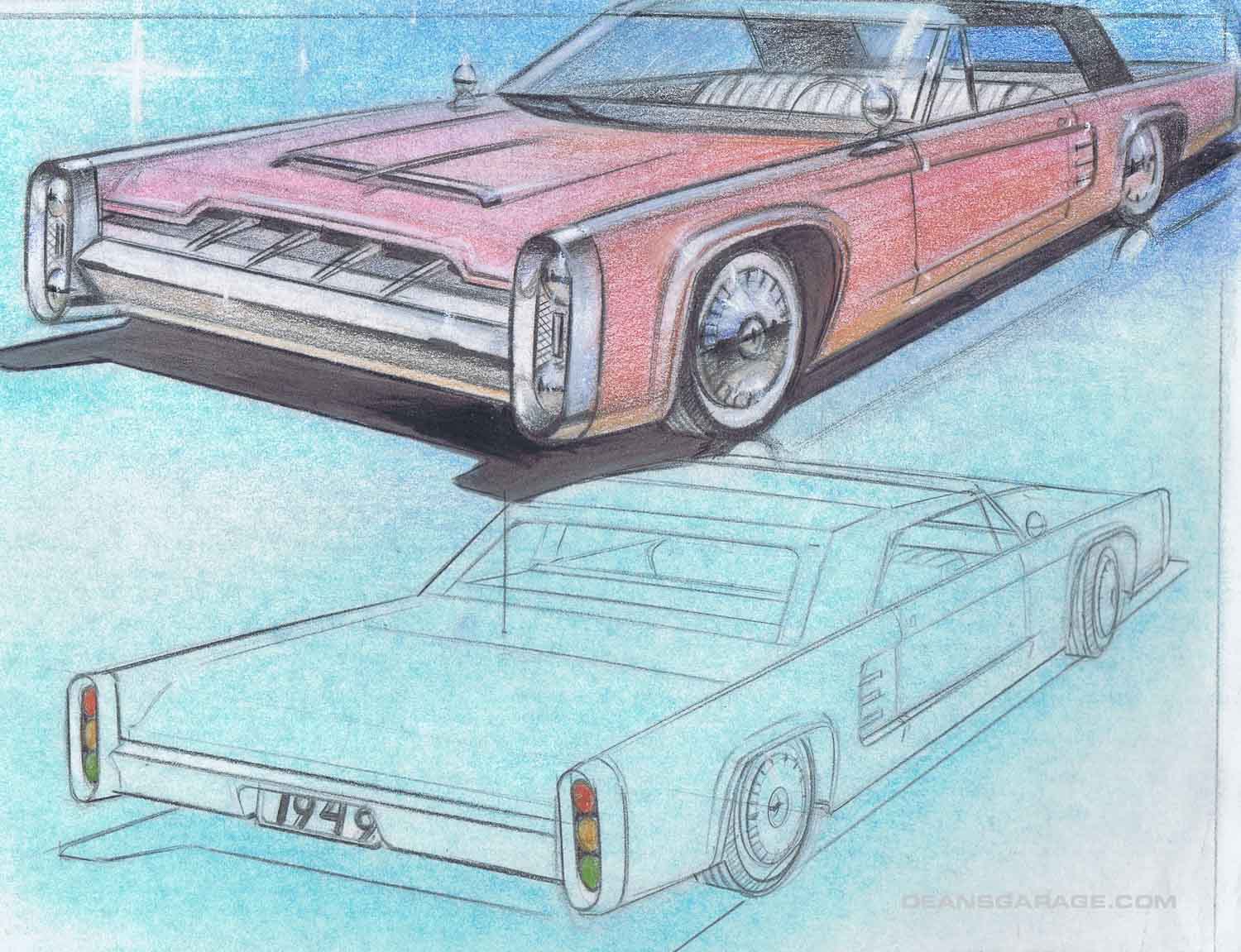

Years later, in 1961, when Bordinat became head of the Ford Design Center, Barbaz drew a sketch of Snyder’s proposed ’49 Continental from memory and presented it to Bordinat. The sketch was very detailed, and Barbaz was proud of it and had it framed. Barbaz expected that Bordinat would fondly remember the car and hang the sketch on the wall in his office. Barbaz was shocked and saddened when Bordinat nervously said he didn’t remember the car and didn’t want the sketch.

In the 1980s and 1990s, after they had retired, Thomas and Barbaz separately prepared sketches from memory of Snyder’s ’49 Continental. And sometime in the early 2000s, Ford designer Howard Payne unexpectedly found four photos of Snyder’s Continental while cleaning out a junk drawer at the Design Department. The photos were of the full-sized side-view drawing made by Thomas in 1947 before the full-sized clay model had been made. Even though more than 50 years had passed, Thomas identified the photos Payne found as being of his drawings, but he couldn’t remember what changes, if any, were made when the car was clay modeled.

After so may years, it’s not surprising that the sketches of Snyder’s ’49 Continental made from memory by Thomas and Barbaz show differences from each other and from the photos, later found of Thomas’ side-view drawing.

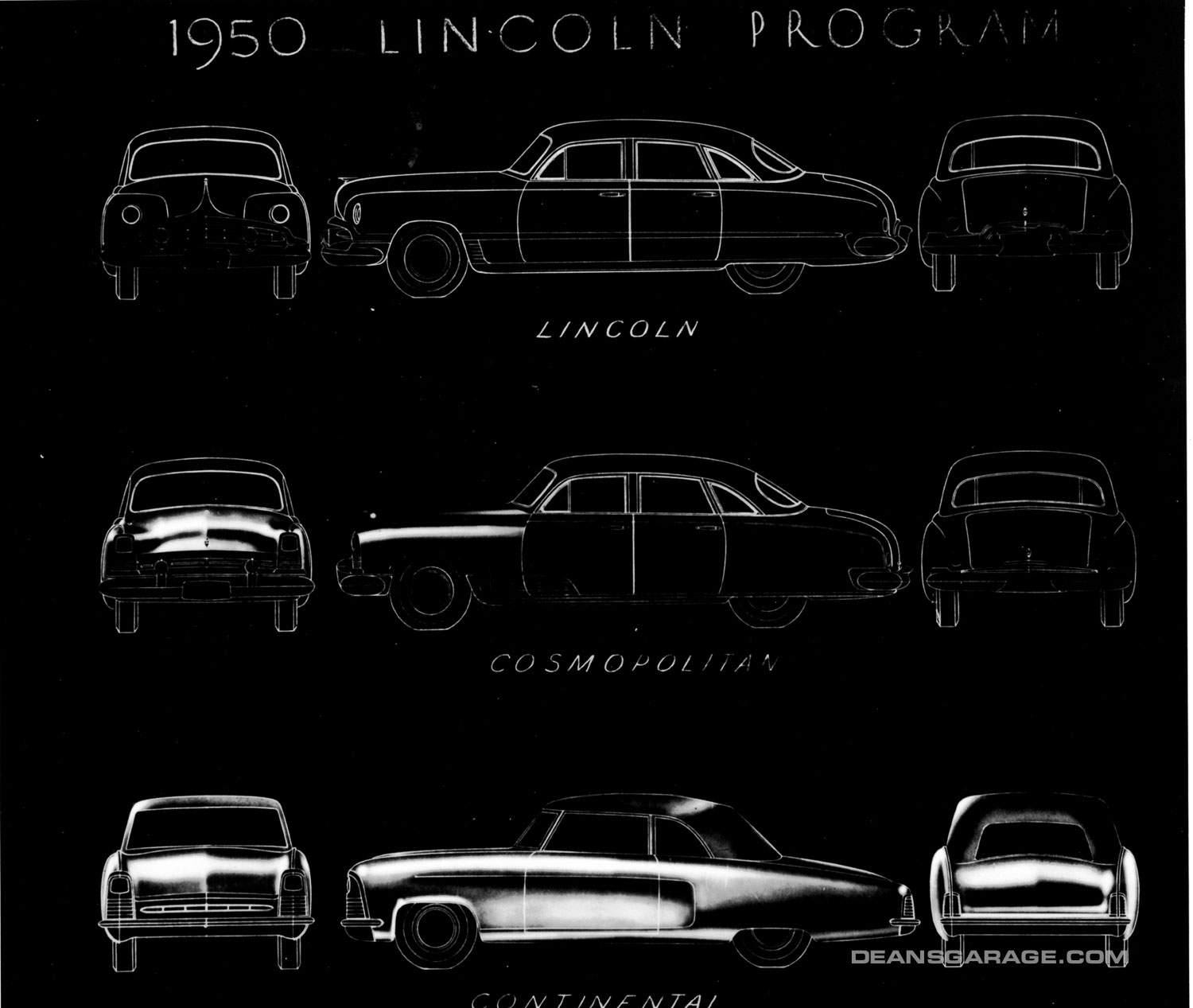

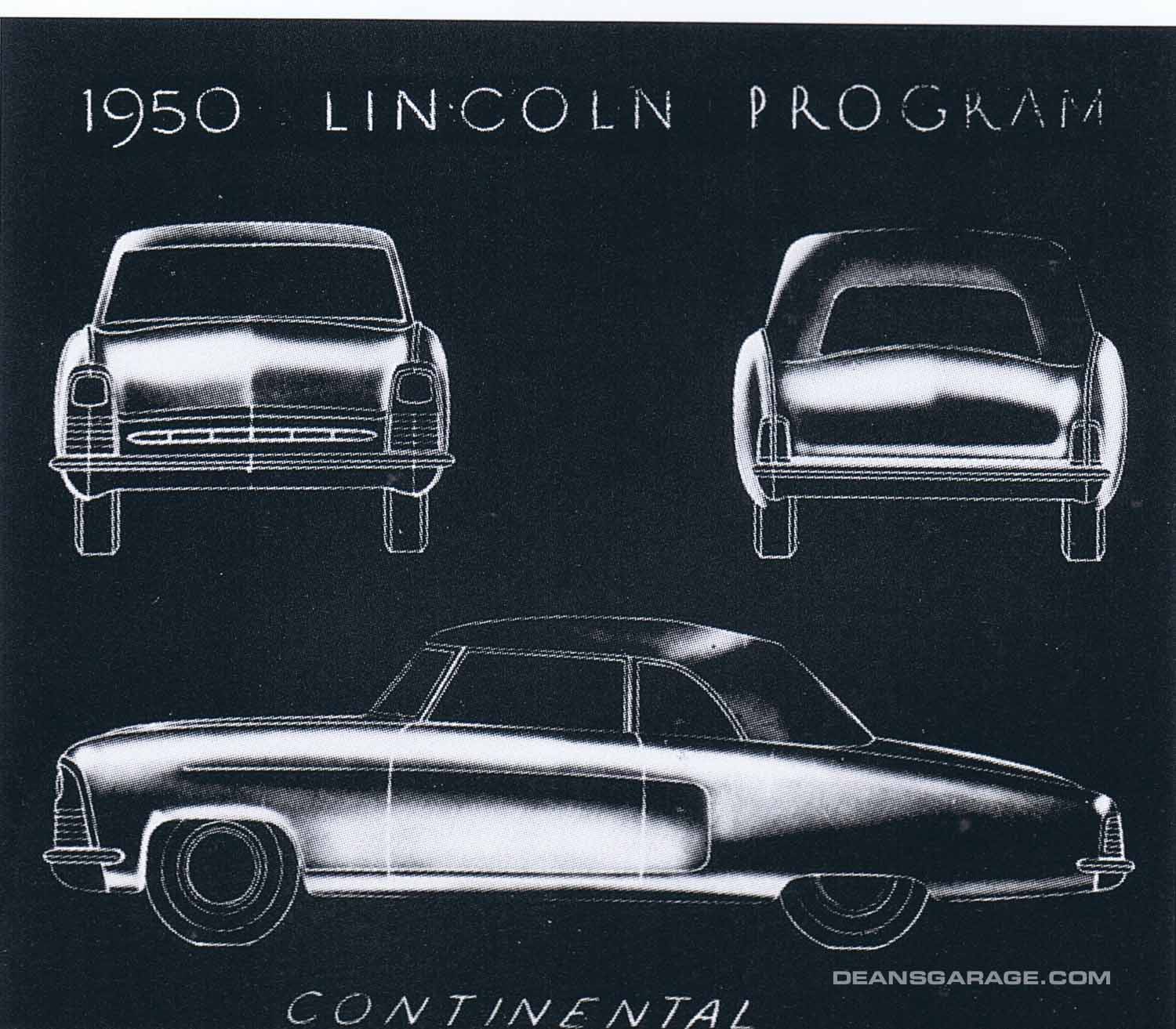

Shortly after his departure, Snyder’s ’49 Continental proposal also became the basis for a proposed ’50 Continental, although it never got beyond the full-sized clay model stage. The ’50 Continental clay model was modified sufficiently so it would not be the basis for any lawsuit by GM. It was also reported by Ford designers that the 1949 and 1950 Continental proposals strongly influenced the design of the 1952–55 production Lincolns, but no new Continental was produced at Ford until 1956—and it didn’t look anything like Snyder’s earlier proposal.

So, thank you George Barbaz, Bob Thomas, (both now deceased) and the other Ford designers who kept the unbelievable story of Snyder’s ’49 Continental alive all these years, even though Ford Motor Co. tried hard to erase it.

Photos: Ford Design

Books by Jim and Cheryl Farrell

Ford Design Department—

Concepts & Showcars

1999, 10×13, 400 pages, Fully indexed

900 photos. Includes 150+ designers and sculptors, and highlights 100 concept cars.

ISBN 0-9672428-0-0

Lincoln Design Heritage:

Zephyr to LS (1936-2000)

2021, 10×13, 480 Pages, Fully Indexed

1,600 photos and illustrations

ISBN 978-0-9672428-1-1

The Ford book is $50 plus $7 S&H (US). The Lincoln book is $85 plus $10 S&H (US). Both books bought together are $110 plus $17 S&H (US). To order, email: cfarrell57@gmail.com

Great recovery, good story and a not-quite-great-enough Continental.

KARL is right. After working in car design studios at GM for many years with many different kinds of people, we were blessed with a consistent management philosophy and it appears to me that the Ford family and the constant turnover of studio management had a strong negative influence on the final design solutions.

Lincoln, with the exception of a few design highlights that were stunners, has really not met the expectations created by Edsel Ford and the first Continental. The first and big mistake that they made was putting that front end on the Continental that looked like a Cadillac after Edsel died. That’s where they had a fantastic opportunity to stay the course and continue to create their own image against Cadillac that would be just as good or better.

If they could do it and I think they could have. It’s possible that Ford Marketing dictated that, I have no idea. That was a change of direction that may have crippled Lincoln forever because it set them on a course of following rather than leading in their own interests.

Above all, Harley Earl was a strategist with a long range plan and he had the designers to back him up. It is unfortunate as America could have easily accomodated two great luxury cars. The fight between the two would have certainly resulted in a higher level of product for both parties and the customers would have received the benefit.

I love reading origin stories. I saw a full page ad in the Sunday newspaper for the all-new ’52 Mercury, and I knew right then, at age 11, I was going to be a car designer! The 52-54 Ford line looked very advanced at the time, especially compared to my mom’s ’49 Mercury. So seeing the influence of this design is amazing, including the aircraft levers on the instrument panel. Thanks

My dad bought a baby blue 1953 Ford sedan with a dark blue interior. I remember two things about it. The tail lights were around and they had a silver bullet in the middle, and maybe a reflector in the middle of that. On the interior it had a hooded speedometer that had a crystal Tinted hood over the speedometer and the needle had a circular opening in it. That would move over the numbers. It was quite spectacular.

I am having difficulty squaring the text with the images. Some of those look indeed like what I would expect a late-1940s design to look like, but there are 2 that look much more angular and very much early ’60s even though they show “1949” on the mocked-up license plate. It would be useful to identify the 4 pictures Howard Payne found as well. I’m confused.

The intrigue regarding Snyder is interesting. I believe I had read somewhere the story of Harley Earl calling someone at Ford (ex-GM exec Ernie Breech perhaps? Or another ex-GM exec at Ford, Harold Youngren? Ford was full of them at the time) to claim Snyder took design documents with him. Who can say if they had grounds to sue, but it was interesting to read that future Ford design head Gene Bordinat credited Snyder for recruiting him over to Ford. Maybe Harley was tired of losing designers to the competition. I read in another piece some years back that Snyder had a bit of a drinking problem, but who knows if that was actually the case.