Rocky Rotella’s books, The Definitive Firebird & Trans Am Guide 1967–1969, and The Definitive Firebird & Trans Am Guide 1970–1981 reveal that he is a true enthusiast. These were not written to end up on the bargain table at Barnes & Noble. They’re packed with history that tell the story of the styling and engineering of the cars, the star players, and power train details that get into the nuts and bolts of why and how Pontiac engines developed power, and how the chassis development set them far apart from their Chevrolet counterpart.

Did you know that DeLorean cooked the books getting the Endura front that Porter wanted? He reported that the Endura front would only be slightly more than a metal part, when in fact it was $30 more. A $30 cost delta would have been a big deal in 1970. As a matter of fact, it’s still a big deal, so that would have been a huge deal in 1970. Plus, this explains why the 70-1/2 Firebird didn’t get a matching Endura rear bumper.

Also, he couldn’t get the Formula wheel made within GM, so he outsourced the wheel against company policy.

Anyway, if you want more of the above, get Rocky’s books. They are exhaustively well-researched and make for very interesting reading.

In this post is a reprinted article written by Rocky that offers some of the flavor of his books. Following that is a gallery of several photos in the two books.

Both books are available through CarTechBooks.

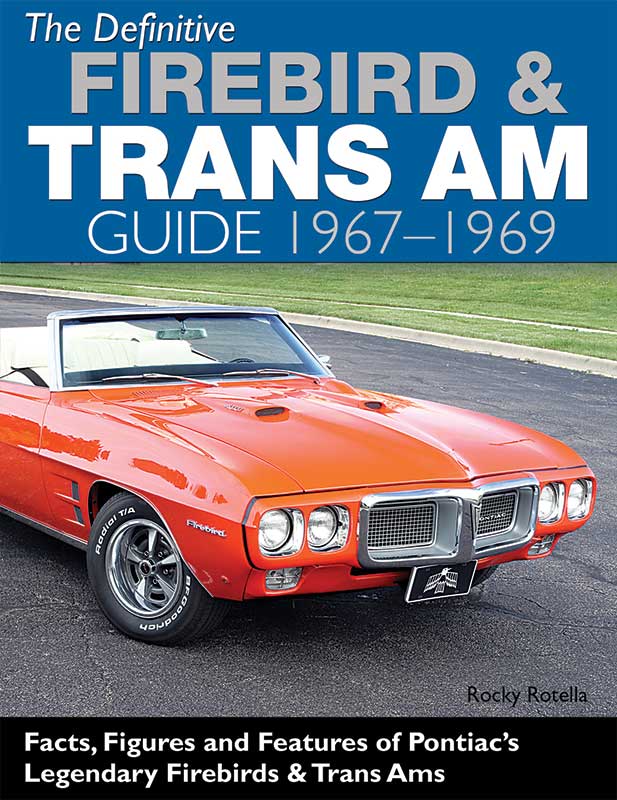

The Definitive Firebird & Trans Am Guide 1967–1969

Pages: 192

Size: 8.5 X 11 (inches)

Format: Hardback

Illustrations: 273 color, 49 b/w

Publisher: CarTech

ISBN: 9781613251492

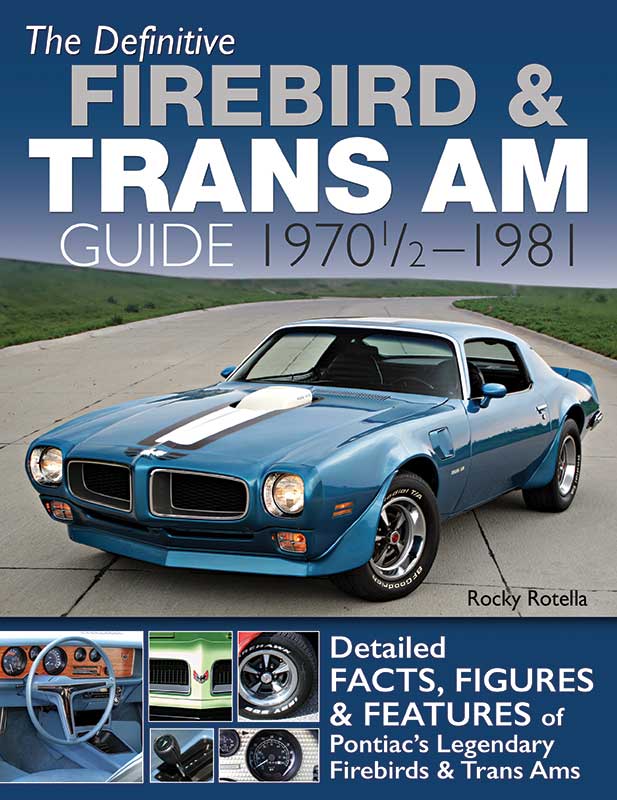

The Definitive Firebird & Trans Am Guide 1970–1981

Pages: 224

Size: 8.5 X 11 (inches)

Format: Paperback

Illustrations: 338 color, 103 b/w photos

Publisher: CarTech

ISBN: 9781613253212

![]()

Well researched, very Interesting and well-written content that includes all aspects of the subject: Styling, engineering, and powertrains. Political intrigue and insights.

Running chapter heads. Legible typeface. Indexed.

Pontiac Firebird History—Designing A Legend

Written by Rocky Rotella on July 1, 2007

Contributors: Factory Photos Copyright 2007 GM Corp., GM Media Archive, GM Design Pontiac Designer Bill Porter’s Influence On The Development Of The Second-Gen Firebird

Published here with permission of the author

Rarely does an automobile gain legendary status, but Pontiac’s Second-Gen Firebird has aptly earned that title. The body style ran for 12 consecutive years-a monumental feat for any vehicle, considering the direction of the mid-’70s performance car market and that the popularity of the performance-flagship Trans Am is as high today as it has ever been. While powerful engines and superb suspension packages have without doubt contributed to the vaunted status, arguably the most critical element to its success is the timeless body styling.

Though any number of Pontiac Studio designers and division engineers in some way contributed to its development, Pontiac Studio Design Chief William L. Porter is often credited with the visionary leadership that generated the graceful body shape. As we celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Firebird’s introduction, we asked Porter if he might share his views on the developmental history of the Second-Gen models, and his thoughts on its strong following today. Join us as we explore the details of the conception of America’s ’70s super car.

The Early Days

Bill Porter entered General Motors’ design staff in 1957 as a summer student before moving into a full-time position the following year. His first foray with Pontiac Studio came in 1960 as a junior designer, and he contributed to the design of a number of models over the following couple of years. As the decade progressed, Porter received promotions that took him away from Pontiac. He would return, however, in 1968 as that studio’s design chief, and his contributions to the division would become legendary.

“Jack Humbert was chief designer of Pontiac Studio throughout most of the ’60s, and he was responsible for the First-Gen Firebird,” recalls Porter. “He was later promoted to an executive position and oversaw the Pontiac and Chevrolet Studios. That’s when I was made chief designer, and he became my immediate boss. Though Jack had already started the second-generation car, the ’69 Trans Am was just nearing production, and I helped finalize some of its fine details like the stripes and fender scoops.”

Humbert and modeler Jerry Snyder had only begun sculpting the basic shape of the all-new car when Porter arrived. Of it, he says, “They started the ‘clay buck’-a fullsize model constructed of clay and foam based roughly on the shape of the preliminary drawings. The body was very round, and I could see that it had the potential to be shaped like the Italian sports cars on the leading edge of modern design at that time. The basic proportions of the package were excellent to begin with, so the car had a lot going for it right away.

“Pontiac and Chevrolet had to share an upper design, which was basically the beltline upward. Henry ‘Hank’ Haga, Chevy’s Design Chief of Studio 2, and I each had our own ideas for the final body shape. Hank favored the angular designs of renowned Italian designer Giorgetto Giugiaro. I was taken with a plainer, curvaceous look featuring long, muscular shapes based on elliptical vocabulary like that of the E-type Jaguars, Lotus 11 and 16, and the designs of Italian coach-building company Pinin Farina.”

Porter and Haga had created two distinctly different concepts from the same basic design, and GM Design management had to choose one common upper to be shared by both the Firebird and Camaro. “My lower body design had a softened crease, or ‘bone’ as we called it, that ran the length of the car, horizontally through the middle of the door. Hank’s crease was sharper in character and located higher on the door than mine, and a similar crease appeared in his roof, just above the side windows,” says Porter.

“Chevrolet Studio had been working on the package longer than we had, and though it was a joint project, they always had more influence because they sold more cars,” he adds. “I was surprised when Humbert told me that GM Design Staff Vice President Bill Mitchell had chosen my upper over Hank’s [yet the Camaro retained its sharper and higher crease down the body side]. He could have as easily chosen Hank’s, and if he had, the Firebird and Camaro would have been quite a bit edgier in character-nothing like we know them today.”

With the direction of the vehicle defined, final body shaping and production preparation became a joint project of Pontiac’s Studio and Engineering staffs. “I had some really talented designers in my team,” says Porter. “You’ve heard the term ‘labor of love’? Well that describes the attitude of the designers as well as the development engineers. The Pontiac engineering team, led by Bill Collins, was equally enthusiastic. We all knew it was going to be something special and were excited to work on such a project.”

Porter assigned his most talented designers, Bud Chandler and Vincent DiSessa, to render the front and rear ends, respectively. “The nose went through many changes,” he recalls. “I even tried a large, central oval opening that resembled the Italian Osca for a short time. Mitchell actually liked it, but we ultimately decided the car needed to retain Pontiac’s split grille identity. That shape would have been tough to replicate in the interior too.”

A few body features that the early models contained were eliminated as the Firebird neared production. “We had rounded corners on all the glass,” adds Porter. “But Engineering found that a square joint where the corners of the side and backlight glass meets was easier to weld. We also planned for a faster windshield angle, but glass technology at the time forced us to pull the base windshield back a bit. The original had too much curvature and distorted the view.”

As the body got closer to what became the production model, Porter teamed with John Shettler, who had recently taken over for Fedele Bianco as design chief at Pontiac Interior Studio. “John and I strongly believed in continuity, and used the exterior theme in the interior as well,” he says. “The shape of the grille could be seen in areas like the dash, seatbacks, door panels, and even the rearview mirror. Though it wasn’t something everyone would immediately notice, we wanted the integration to be more of a subliminal feel.

Nearing Production Until the Trans Am’s debut in 1969, Pontiac had just one basic First-Gen Firebird available in both coupe and convertible styling. The Second-Gen family did not include a convertible, but it did contain four distinct model variations. “Bill Collins and I decided that we needed to market four different Firebirds,” says Porter. “The base model would satisfy the sales department’s low-buck needs, while the Esprit would be the plush boulevard cruiser. The Formula was planned as the low-buck performance model, while the Trans Am would be the top performer and a serious aerodynamic statement.

“Chevrolet had done some wind-tunnel testing on the body, and I received a copy of the aerodynamic report from our aero engineer, Doug Patterson. I used it to improve the T/A’s profile,” he says. “The front spoiler is the most functional, but the rear spoiler, wheel flares, and front-fender air extractors are functional too. We learned that the car does need a slight rake, however, to get the greatest benefit in reduction of both lift and drag from the spoilers. I also designed a pair of highly effective Ram Air scoops that were placed in the high-pressure area on the leading edge of the hood.”

Competitive performance models such as Dodge’s Challenger, Plymouth’s ‘Cuda, and Ford’s Mustang contained a functional Shaker scoop. According to Porter, Bill Collins and Herb Adams wanted that feature for the Trans Am too. “I was very against it since it cut into the hood’s slender spine, and to make ours unique they faced the opening rearward. I argued that the scoop was too far forward of the high-pressure area at the base of the windshield to be effective, but I eventually saw the logic. It was entertaining to watch it shake and to control it with the throttle. The air valve opened under heavy acceleration too.”

Upon accepting the fact that the Shaker was a Trans Am mainstay, Porter shaped it to follow the overall theme, and began searching for ways to integrate it into the rest of the car. “The bird that had appeared on first-generation cars had downward-facing wings, and it just looked dead. I felt we needed one that looked alive with upward-facing wings giving the appearance that it’s flying, and I began working on it,” Porter says.

“I thought a large version of this bird on the hood with its wings wrapped around the scoop would make it become a more integral part of the car. Ted Schroeder drew a sketch we hung up in the studio that everyone seemed to really like, but apparently Bill Mitchell never saw it,” he recalls. “Herb Kadau, Pontiac’s liaison to the studio, sent us a show car and I sent it down to the paint shop and started laying the bird out onto the hood. Apparently Mitchell walked through while I was at lunch that day and flipped out when he saw it. When I got back to my office he was on the phone telling me how much he really disliked the idea. I had to hold the phone away from my ear, but I heard every word! Needless to say, the hood bird went no further.”

Still considering ways to better incorporate the scoop, Collins and Adams proposed the idea of a single racing stripe to Porter. “They brought a car to the studio with the skunk stripe taped on, and it really helped visually integrate the scoop,” he says. “I refined their design a little, and we planned on using 3M’s new dot-pattern process to give the decals’ black border an airbrushed appearance into the color, but it became a problem as the dots tried to make the transition around the rounded corners. The pattern went haywire and just didn’t look right, especially on the white stripe where the dots showed up so vividly, so we went with a solid black border. We kept it on the blue stripe because the problem was less noticeable, but there was a delay getting them into production.”

Porter admits to having reservations about white as an exterior color on the Firebird since it can hide a vehicle’s body shape. “There aren’t any shadows and there’s nothing to reflect the curves; it works better with sharper body angles. In spite of my doubts, however, it worked well with the Trans Am because of all its angular spoilers, but a white base-model Firebird looked too plain in my opinion. Metallic colors or medium and dark solids like British Racing Green or Ferrari Red can really accentuate the curvaceous body. Those are the colors I wanted to see the Trans Am in.”

Production Begins Though the production Trans Am was limited to Polar or Cameo White, and Lucerne Blue through 1972, Porter says he was pleased to see Brewster Green and Buccaneer Red offered in 1973. “I don’t think the green was overly popular, and the red was more tomato-colored than I liked. Red pigments are not only very expensive, but I was told that a rich red wouldn’t flow well in the reflow oven. They said it needed a substantial amount of white or black pigment to get red to flow properly when heated.”

As we learned in Don Keefe’s article “A Honey of a Design” in the Mar. ’02 issue of High Performance Pontiac, Porter developed a high-strength Honeycomb wheel to complement the Trans Am’s total functionality. Although he intended for it to be constructed of cast aluminum, cost concerns forced Pontiac to find an alternative method of production by the time it was released in 1971. The cast aluminum gave way to a steel wheel with a molded urethane fascia using a process known as polycast. “I wasn’t happy with the decision to go that route,” Porter says of the choice, “but at least the design made it into production.”

Like the Honeycomb, Porter had to accept a few compromises once the Firebird was in production, too. “I have always been against anything on a vehicle that isn’t totally functional, and all ’71 Firebirds besides the Trans Am received ornamental fender vents. This was actually a request from the sales department so buyers could easier identify new models from used on the dealer lots. I didn’t like the look and it lasted one year. To separate ’72 models from others, we changed the grille pattern to the elongated honeycomb design to better match the Honeycomb wheels. It was also a good excuse to remove the fender vents since the grille now provided model-year identity.”

Ever increasing federal bumper regulations began taking their toll on the front and rear treatments. The nose’s internal structure changed for 1973. Porter received the requirements for the ’74 model year and knew that major changes were inevitable. “I cringed when I saw them. It required an entirely new nose,” he recalls. “We got the news in 1971 and just as I started working on it, the Studio was split into two separate but smaller studios, just like Chevy had been for a couple of years. I was assigned to Pontiac 1, and the Trans Am went to Pontiac 2. Ron Hill lead Pontiac 2 for a short time and continued work on the ’74 model.”

Porter’s Comments

John Schinella soon replaced Ron Hill as design chief at Pontiac 2, and Porter was transferred from Pontiac 1 into an Advanced studio. “I didn’t really follow the car that closely in later years, but Schinella really kept it alive,” says Porter. “He did an incredible job during a disastrous performance-car market and deserves all the credit he can get. The deck couldn’t have been stacked any worse against the Firebird, and he kept the looks fresh and injected it with new ideas.”

He continues, “It certainly changed a lot over the years. Mitchell always wanted the wrap-around backlight, and Schinella got it into production. But I was really surprised when I saw the hood bird appear on the production Trans Am in 1973. Schinella was a better salesman than me because he sold Mitchell on the idea! Looking back, I can say although I was initially against the hoodscoop, I now know that without it there would be no hood bird, and together those two really identify the Trans Am.”

When asked what model year Firebird he likes best, Porter answered like most true enthusiasts, “I like some years better than others, but if I could have any, it would be a Lucerne Blue ’72. It has the elongated-honeycomb grille that matches the Honeycomb wheels.” As a parting question we asked Porter how it makes him feel, as a designer, knowing that a vehicle he designed has such a loyal following nearly four decades later, and if he ever envisioned it to be so widely popular among old and young hobbyists today.

He humbly replied, “Somehow, and this is a theory of mine, a car design, like any work of art, embodies the feelings and emotions of the designers who create it. When the chemistry of talent, experience, intelligence, and enthusiasm all come together at the right time, the car begins to take on a life of its own and emits certain vibes. Some designs are like fads-their vibes are transient, but others continue to have appeal over a long period of time and become classics. Needless to say, I am very grateful that I was at the right place at the right time to contribute to a car that still gives enjoyment to people many years after it was created.”

Conclusion

In an age where some consider late-model auto styling rather mundane, only now are we gaining an even greater appreciation for the efforts of Porter and his entire design team. Nothing today bears even the remotest resemblance to the Second-Gen Firebird or its timeless styling and, when on the road, its flowing body lines still command the attention of enthusiasts and the general public alike-a true testament to its beauty and classic looks. So the next time you have an opportunity to view a Second-Gen Firebird model up close, step back and take in its entire shape. You, too, might realize how lucky we are to have had Bill Porter and his design team on our side!

Special Thanks To Jeff Denison, Robert Tate and Brian Baker of GM Design for going above and beyond the call of duty to provide most of the design photos shown in this story.

Cover of The Definitive Firebird & Trans Am Guide 1967–1969.

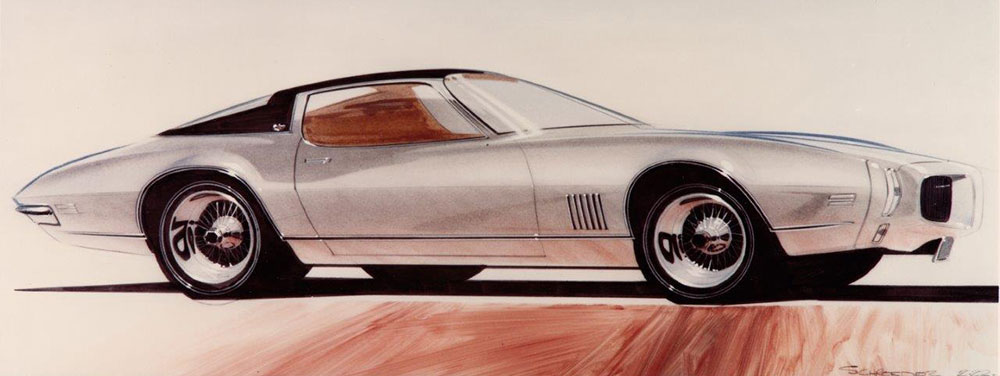

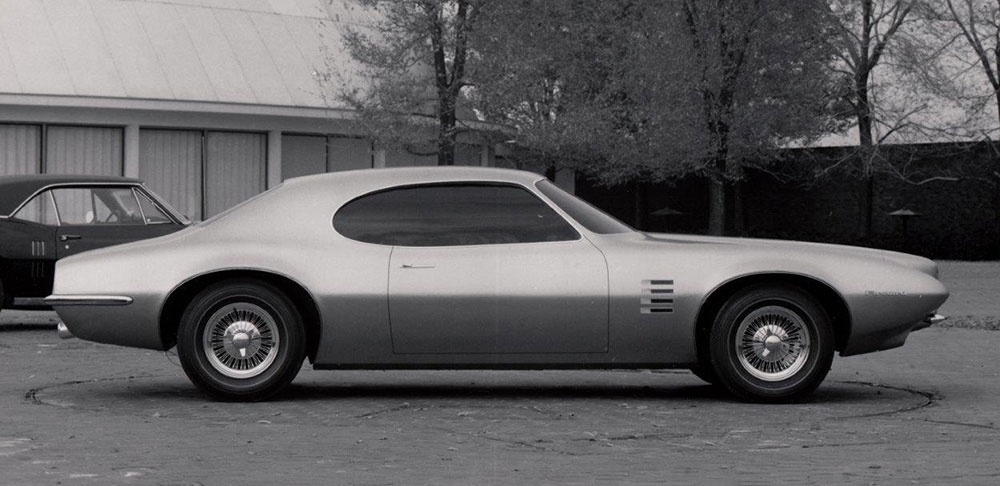

A short-lived, two-seat F-car variant with a shortened wheelbase of 8-inches.

John DeLorean approved a special model Firebird for 1969 and contracted Gene Winfield to create an appearance package. Harry Bradley’s proposals were presented to Pontiac, and they became the basis for the first Trans Am.

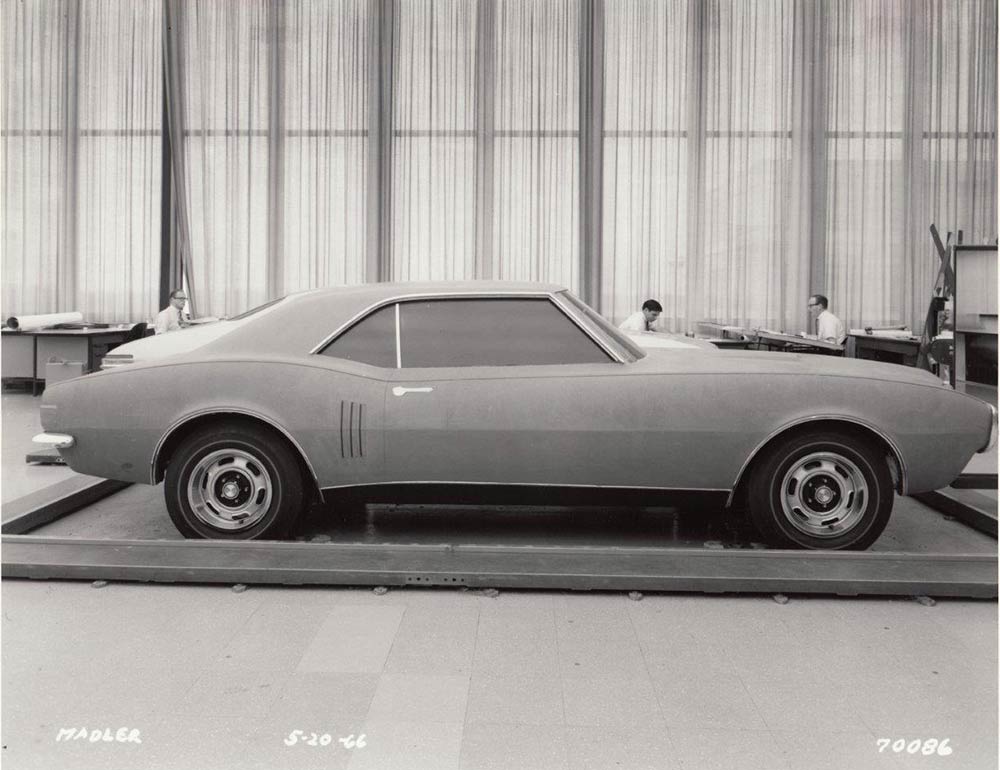

Pontiac was handed the nearly completed Camaro and assigned the task of creating a distinctive model. The changes allowed were minimal because timing was tight.

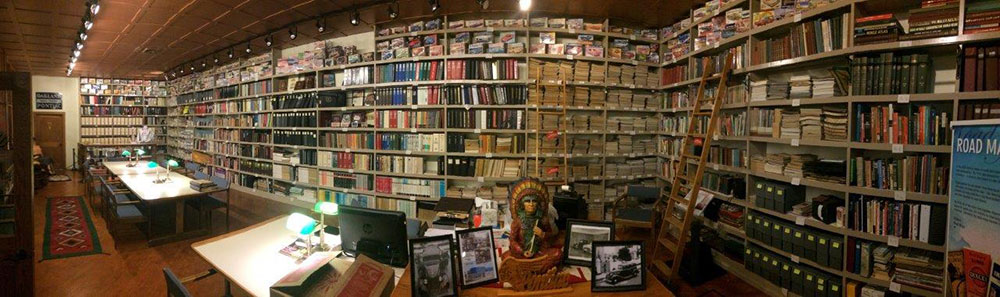

The expansive library in the Pontiac-Oakland Museum and Resource Center (POMARC) located in Pontiac, Illinois.

A ’69 Trans Am on the drag strip at Riverside International Raceway.

Pontiac did a good job separating the appearance of the Firebird from the Camaro in spite of the limitations.

The story behind the creation of the ’69 Trans Am is quite interesting, and reveals the innovative thinking of John DeLorean.

A re-created scene mimicking the briefly lived John Wangers’ GTO ad of a GTO on the prowl posed on a Woodard Avenue turnabout.

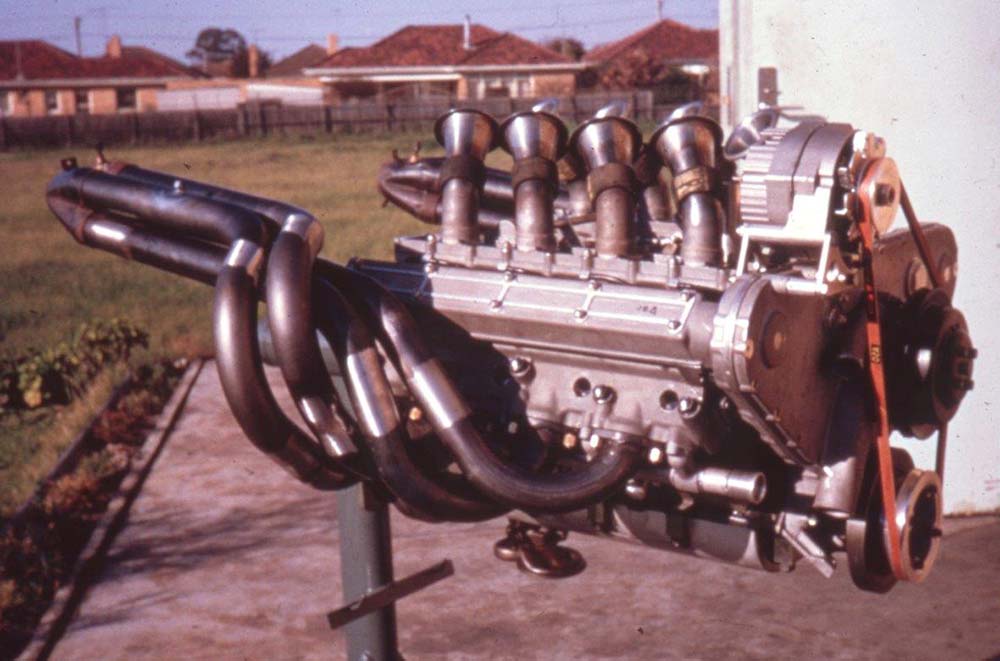

In 1968 John DeLorean commissioned Brabham (Repco of Australia) to build an experimental 303-ci Pontiac V-8 using overhead cam technology of his Formula One engines.

Cover of The Definitive Firebird & Trans Am Guide 1970-1/2–1981.

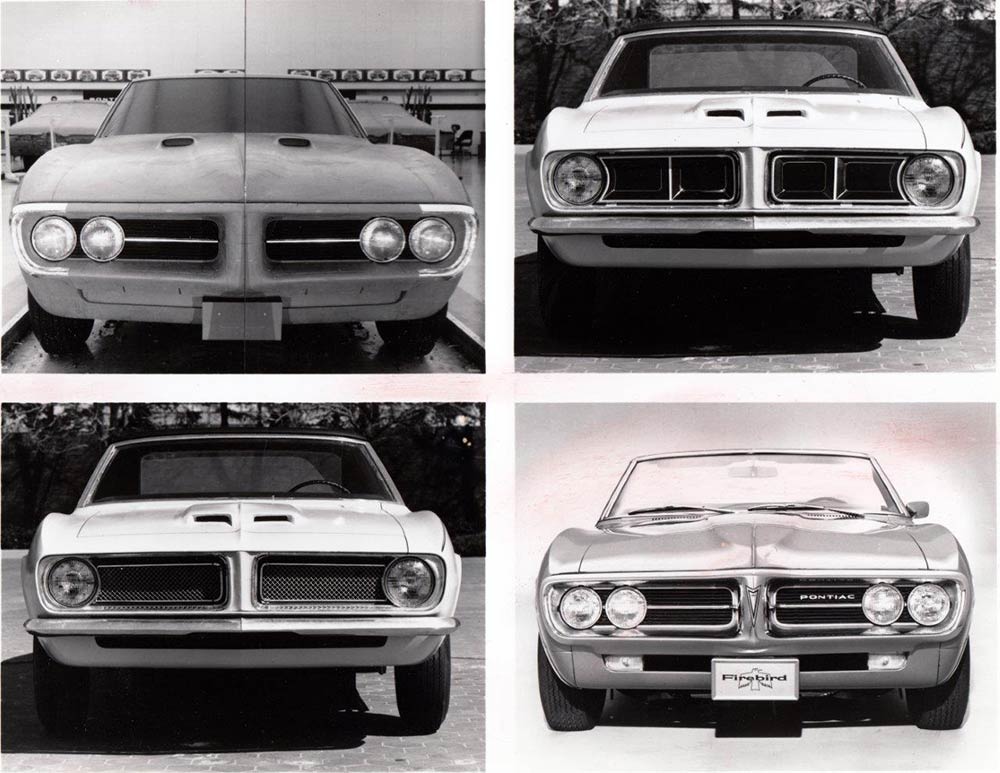

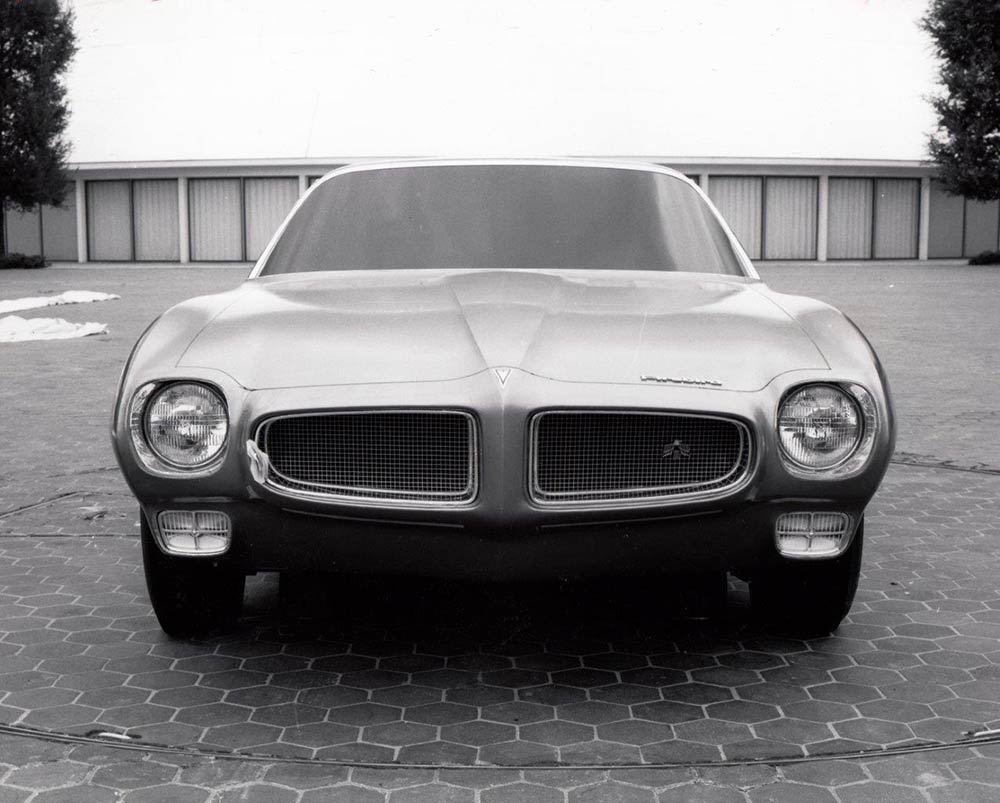

In the spring of 1968 the front has lost the chrome bumperettes that Mitchell wanted and now has the character of the front that made production. Bill Porter’s last battle was to get rid of the sharp plateau on the hood which was out of character with the European form vocabulary of the rest of the design.

When Bill Porter inherited the Firebird project, he liked the soft bone through the bodyside, but felt that the overall forms lacked tension.

The forms of the Jaguar C-type influenced Bill Porter’s form vocabulary the design of the Firebird.

A 174 day UAW strike seriously limited 1972 F-car production.

Jerry Titus raced a Firebird for TG Racing during the 1970 season and was quietly backed by Pontiac Engineering.

A young Herb Adams in Pontiac’s dyno lab with a SD-455.

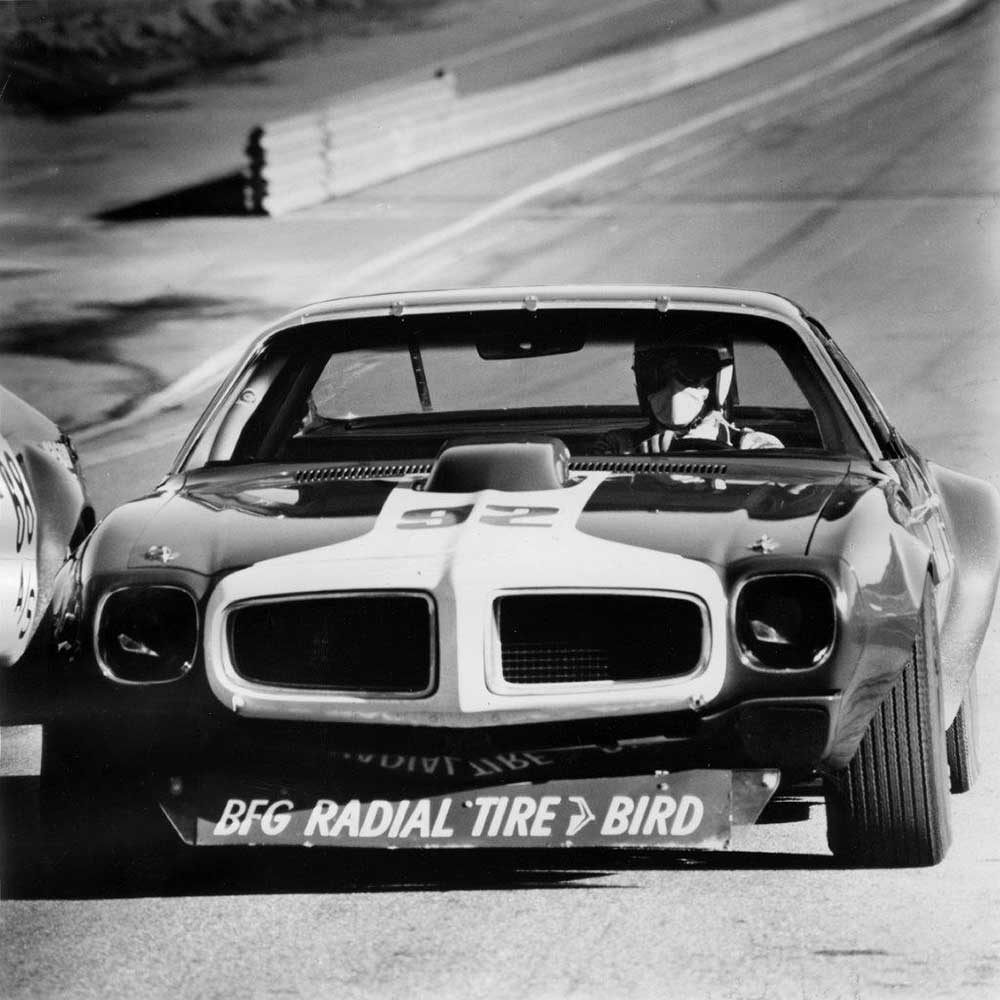

BFGoodrich acquired one of the SCCA prepared Trans-Am Firebirds and competed successfully in SCCA’s street car class to prove the merit of their Radial T/A tires.

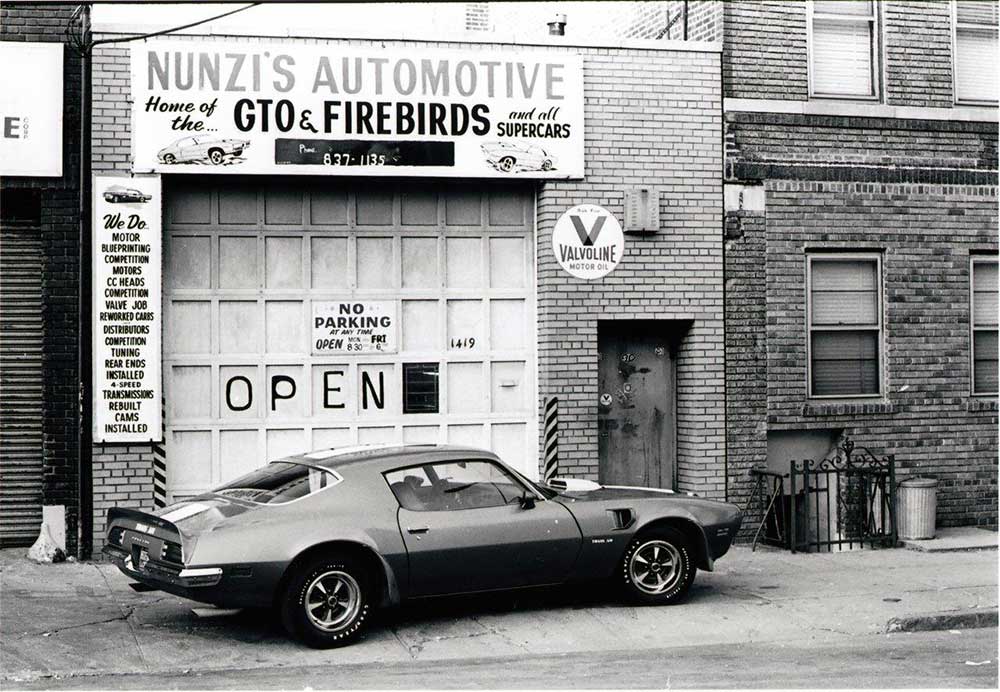

The simple magic preformed by Nunzi’s Automotive of Brooklyn, New York, consisted of carburetor and distributor tuning that reduced quarter mile times from 14.58 to 14.04 at 103.2 mph and revealed the H.O.’s true potential.

The special-order Cardinal Red TA produced for Berdie Martin, Chief Steward of SCCA’s Trans Am.

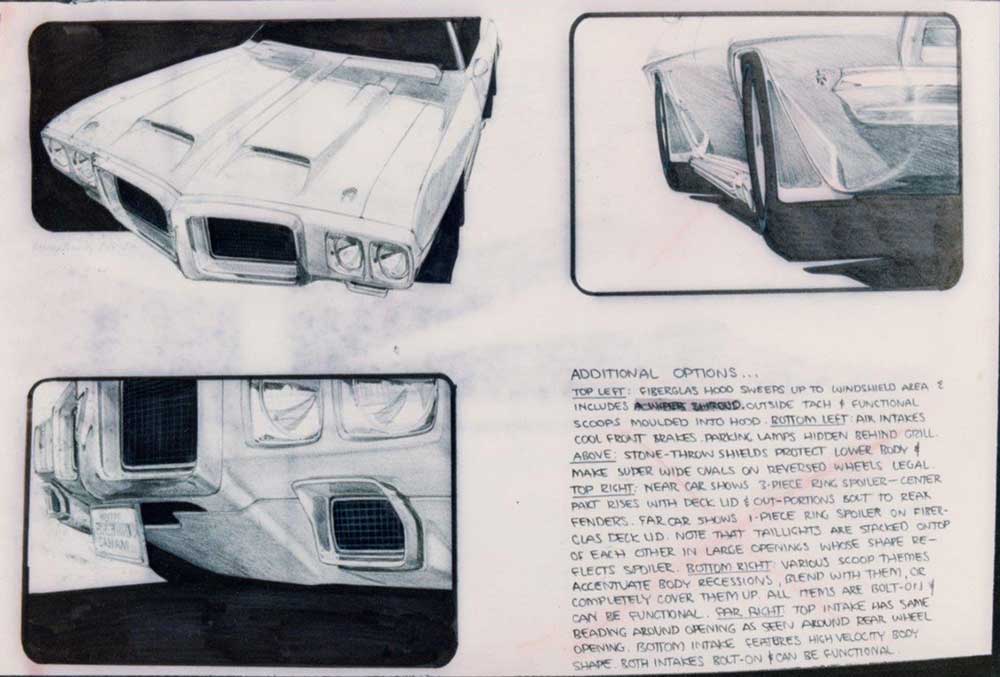

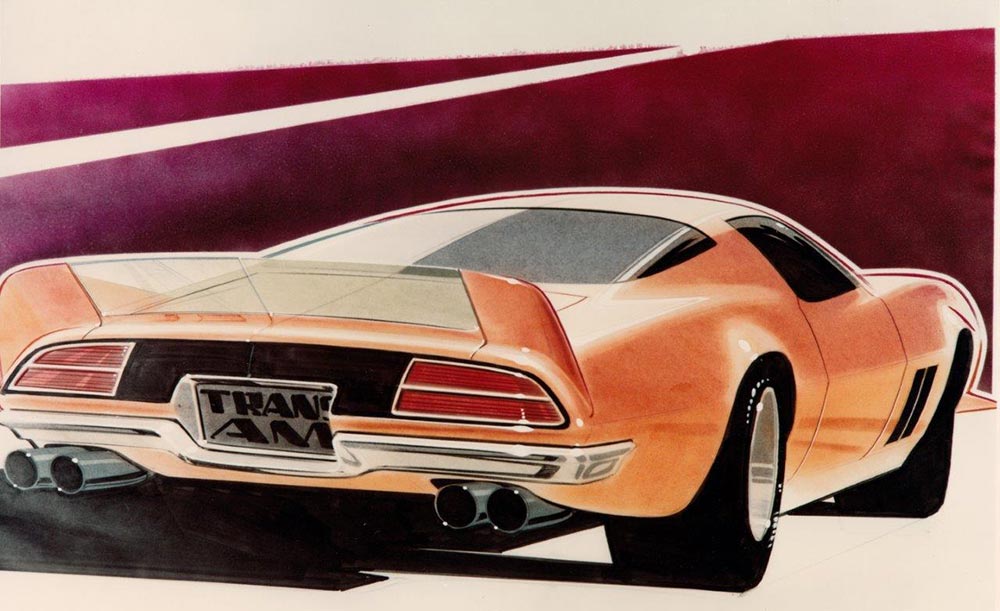

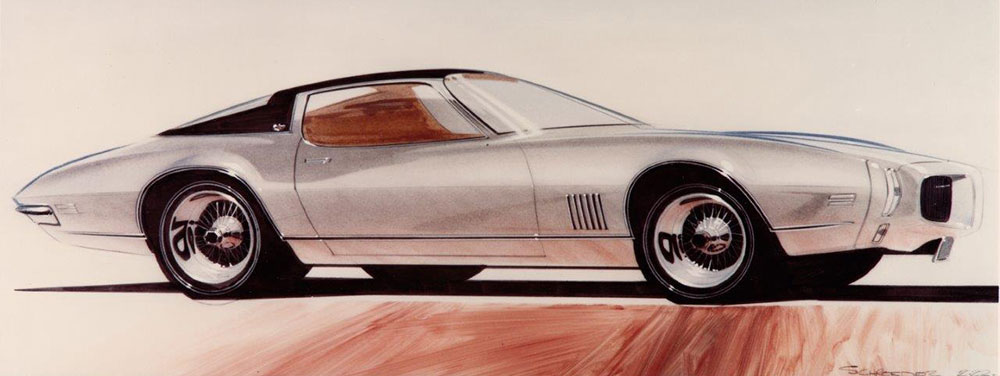

Ted Schroeder explores styling possibles interpreting the aerodynamic data intended for the Camaro.

Firebird Esprit proposal by Ted Schroeder.

Trans Am ideation by Ted Schroeder.

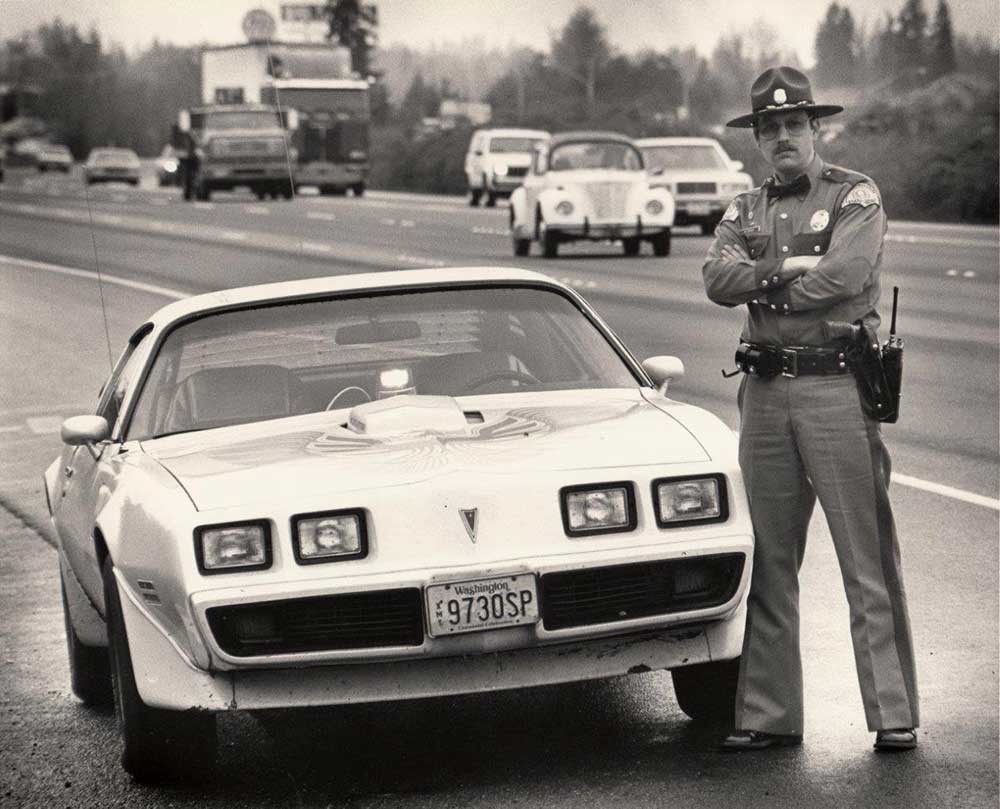

An unmarked pursuit 1981 Trans AM used by the Washington State Police.

The Iconic Second Generation Firebird front.

Great to see this iconic era covered in detail with commentary by those who made it happen….one of the great forms of the Mitchell era! A must for my library!

I believe Bill Porter set the standard at GM for the idea of creating a design with forms that are defined by “reflections,” not “edges.” Also, the forms themselves were incredibly beautiful and sensitively worked out.

He is right that his team was great. He had a hand in the development of some of the best designers to ever work in the car industry. I also believe that his grasp of form also influenced some of the better modelers. Good modelers are rare, smart; most manage to get up from their immediate job to look at the whole car more than occasionally. If they didn’t, they never couldn’t have coordinated a Porter inspired design. The designs were “of a whole.”

He came to Art Center when I was a student in seventh semester. As a direct result of his visit, (and tutelage) I spent the next two semesters redoing my entire portfolio.

Thank you for the article, really enjoyed it

The time was 1969 and I was about to decide on a (boring) new 1970 GM four door sedan. My wife then said to me, “What car do you REALLY want?” to which I replied, “I really want one of those new Firebirds!”. So, with her encouragement, I purchased a new 1970 Firebird. Then for Christmas, my wife surprised me with a set of four Kidney Halliburton Aluminum Wheels which I immediately installed, with new tires, on my Firebird.

The interior was a masterpiece – John Shettler had captured the shape of the front end and designed the instrument panel accordingly. We drove that car a lot, on long trips to Florida, usually with our bicycles on the back. In fact, I drove it with bicycles on the back once to New York City where I had an appointment with GM Overseas. It was a beautiful car, but I sold it a few years later to a friend of a neighbor. Fond memories, the 1970 Firebird is still one of my favorite automobiles. Thanks Bill Porter and John Shettler!

Ken Pickering

@Tom Semple,

“He came to Art Center when I was a student in seventh semester. As a direct result of his visit, (and tutelage) I spent the next two semesters redoing my entire portfolio.”

Tom, I can truthfully say the same thing about you:

Tom came to Art Center when I was a student in seventh semester (early 1977). As a direct result of his visit and rendering of the Aerovette over two afternoons, I spent the next year redoing my entire portfolio. I left ACCD after the 7th semester without a degree, and as mentioned above, went home and redid my entire portfolio. I then applied and got a design position with a museum design/build company in 1979. With that same portfolio that secured my first design position, I applied for a design position with Pininfarina in the fall of 1979, and in May of 1980 I started designing there. Tom, you really changed the direction of my life and set me up with the skills needed in my industrial design career ahead. Thank you.

Walter T. Gomez