One In The Eye

Published in Top Gear Magazine (Probably in 2002)

Written by Richard Fleury

Photos by Giles Park

Also posted on Undiscovered Classics, April 4, 2010

BACK IN THE MID-’50s, the Golden Age of American motoring, a schism developed among drivers. Battle lines were drawn between the Bigger Is Better school of automotive design and the European invasion of small, lightweight, individualistic and, above all, cheap cars. It was Ford Thunderbirds versus Fiat 500s. Buicks versus Beetles, Plymouths versus Porsches. To say opinions were divided would be a grave understatement. It was daggers at the drive-in.

Out of this cultural maelstrom emerged a legend. The fashion for quirky European imports spawned a car the like of which has never been seen since: the Cyclops.

The term ‘minimalist masterpiece’ is overused nowadays, but the Cyclops (The Mk-I prototype remains shrouded in mystery to this day) was the real deal. This diminutive design classic was manufactured in Modena, Italy, by the shadowy firm by the name of Automobili Cyclops SpA.

The Cyclops was compact to the point of abject torture. It made the Mini seem bloated by comparison. The flat-sided body shell fabricated from recycled Cinzano signs (allegedly stolen from the roadside by Cyclops employees in the dead of night to keep costs down), was ingeniously designed to accommodate two average-sized adults in profound discomfort. The driving position was fetal and the Cyclops boasted all the modern creature comforts of an empty bucket. Specs were spartan, a fact reflected in the exceptionally affordable price tag of $14.32.

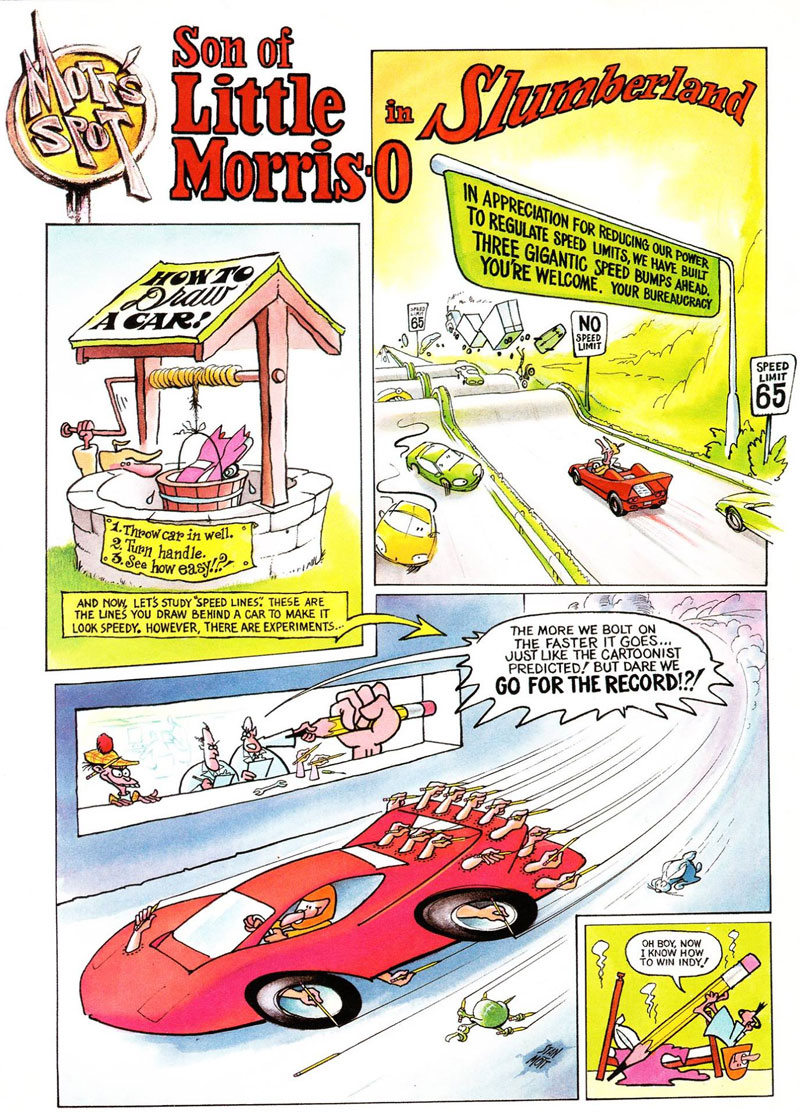

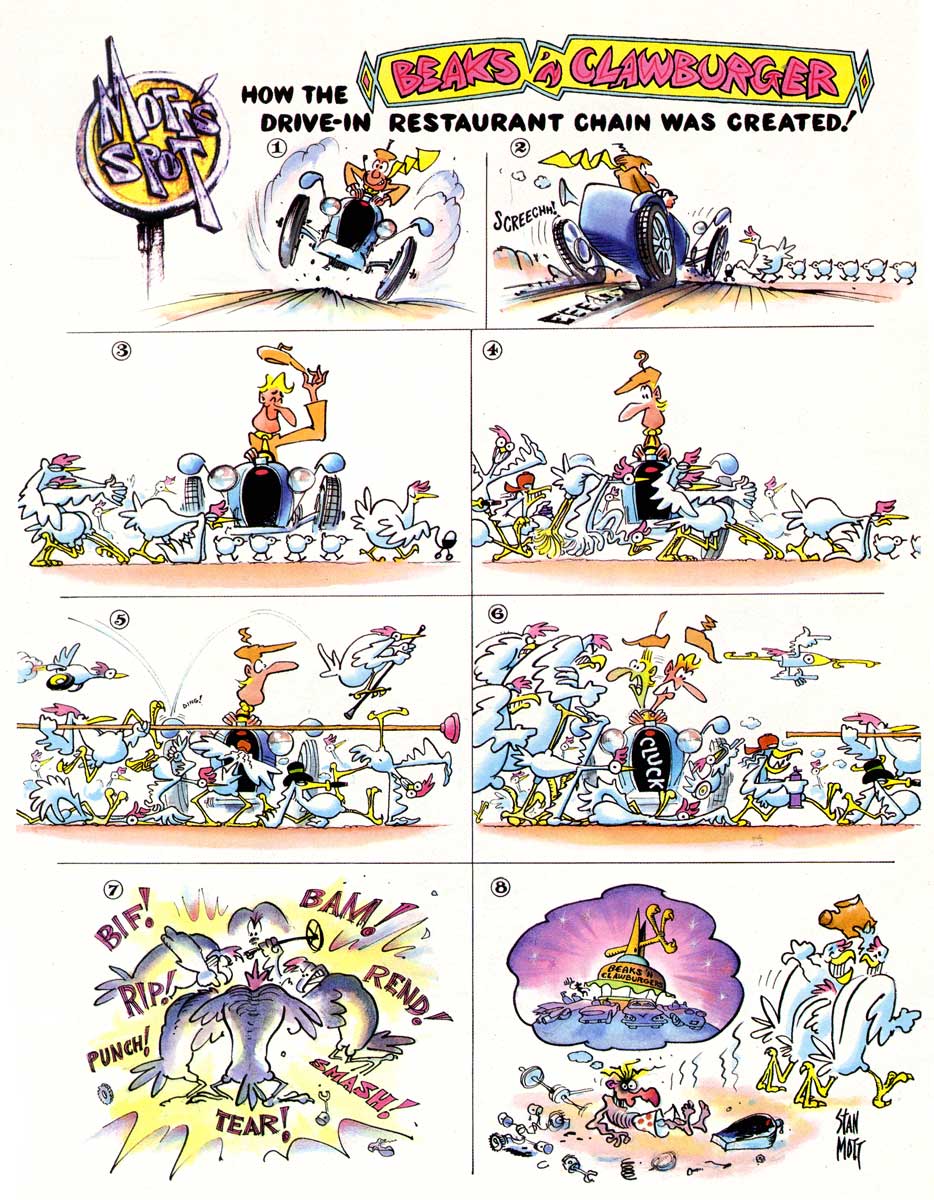

Precise details of the car were scarce. But America’s august motoring publication Road & Track ran regular stories and cartoons submitted by Cyclops’ official U.S. importers, two distinguished gentlemen named Trebor Crunchcog and T. Tom Meshingear. The readers of Road & Track took it to their hearts and were soon clamoring for information.

The magazine printed an increasingly unlikely succession of David and Goliath yarns in which the magical microcar beat all comers to win the world’s most prestigious motor races, including the East Africa Rally, Le Mans, and the Indy 500. Stoked by this track pedigree, demand went through the roof.

Bur there was a snag. Anyone who wanted to buy a Cyclops soon encountered problems at the supply end. One vital consideration was overlooked—it didn’t exist. Nevertheless, Cyclops became an icon and an institution. It was, and remains, the most popular non-existent automotive marque in America.

As with all the best satire, behind the wild flights of imagination lurked a remarkable attention to detail. And the fertile mind behind the Cyclops belonged to a maverick young car designer called Stan Mott.

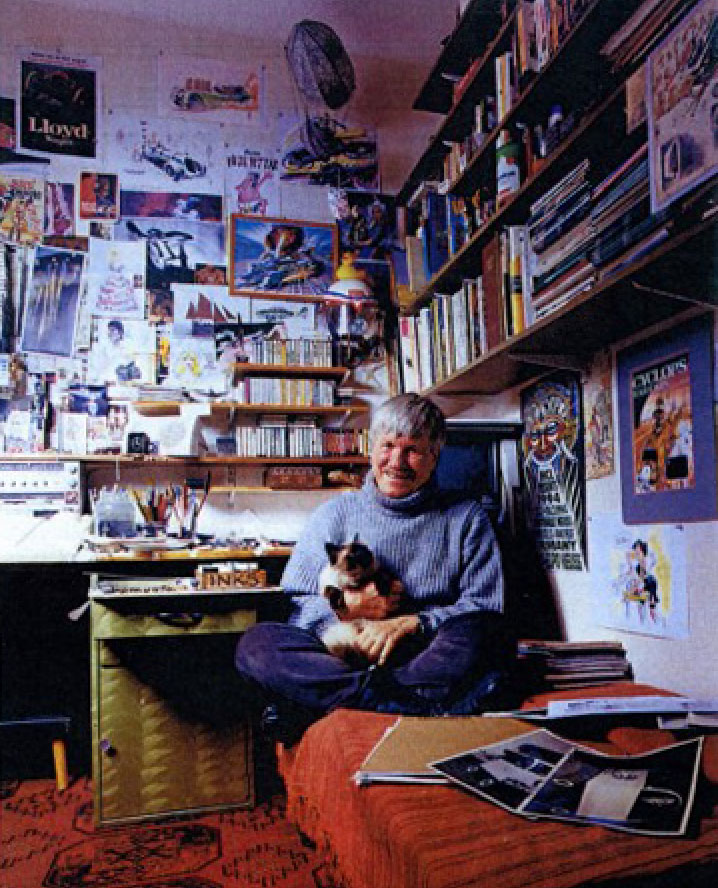

Now 68, Stan’s sifting opposite me in a hotel bar in his adopted home town of Neuss, just outside Dusseldorf. In the middle of a vivid anecdote about a near-death experience at sea, he suddenly pauses, fixes me with a piercing eye and asks, “Have you ever taken acid?” The question is, | think, a bit forward. We only met ten minutes ago and besides, I’m sill only on my first beer.

If ever there was a person who didn’t require hallucinogens, that person is Stan Mott. In fact, his life has been one big trip. Cartoonist, writer, hot-rodder, car designer, inventor, round-the-world yachtsman, some time radio DJ, and global go-kart adventurer, his CV reads like…well, like a long list of outlandish and incongruous jobs. But more about that later.

A forerunner of underground comic book arrises like Gilbert Shelton (The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers) and Robert Crumb (Fritz The Cat), Mort’s cartoons share similar demented imagery and subversive humor.

His first Cyclops story, “Beyond Belief” appeared in the March ’57 issue of Road & Track. It was, he explains, part reaction against the excesses of the U.S. auto industry and part elaborate spoof of the European sports car fad of the time. Its popularity was helped by the fact that Mott was what our colonial cousins cali a “gearhead.” He not only understood the nuts and bolts, but as a stylist working for General Motors was ideally placed to snipe at the foibles of the auto industry.

Working with him in the belly of the beast was Robert Cumberford, another young designer. The pair, who’d met at high school in L.A., began freelancing for car magazines and soon realized that poking fun at their employer was much more enjoyable than designing the rump of next year’s Chevy.

“We took all the standard myths. Everything was an in-joke. And GM was not alone. We took on the whole industry,” he says. “I just did it because it was fun and I was angry and it took off.”

Inevitably, GM took exception to the pair’s extra-curricular activities, anti-establishment tendencies and pretty soon Stan was a rebel without a job. So the pair became full-time contributors. Stan drew the cartoons, Robert wrote the stories and with the collusion of legendary Editor John Bond, the Cyclops myth grew. They even built a Cyclops II and the eagerly anticipated road test appeared in the September ’59 issue. Mott was fortunate enough to secure a ride. It was, he says, “Absolutely the most ghastly, unsafe, terrible experience. So it was perfect.”

Ergonomically excruciating it may have been, but the car’s longevity as an automotive in-joke remains unrivaled. Over 33 years, Road & Track ran 22 Cyclops articles before Mott moved to rival Automobile magazine which published the last Cyclops cartoon in 1994.

“People really liked to get in on it,” says Stan. “That was the fun part.” Cyclops specs were listed in po-faced motor industry journals. Elaborate scale models were featured in Model Car Journal. An American racing team, Jert Racing, built a track version, the Cyclops GT “Fantastico.” Meanwhile people wrote applying, quite sincerely, for jobs at the factory. “I wrote back celling them we didn’t take just anyone at Cyclops. We’re extremely particular,” grins Stan. And, in an exquisitely ironic twist, GM’s styling department even wrote asking for Cyclops sales brochures. “That was our most treasured fan letter,” he chuckles. “From the tame corporation that bounced me 12 years earlier, requesting information on my line of automobiles! I doubt if they ever caught on.”

Sadly, a planned Cyclops book never came to fruition. The ultimate accolade came last year, however, when the Cyclops came 51st—ahead of both the Ferrari 250 GTO and the E-Type Jaguar—in Road & Track’s 100 favorite cars of the twentieth century.

The son of a Californian policeman, Stan bought his first car, a 1930 Ford Roadster, at the age of 15. “I got into cars by accident,” he explains. “It was what was going on when | was a kid in L.A. My father and older brother were into cars, so it’s probably genetic.”

At 17, he joined SoCal’s Road Hogs car club. “A bunch of like-minded bums from which I learned a lot about building engines,” recalls Stan fondly. They would borrow go-faster bits from each other to squeeze another few mph out of the top end. “These were young guys whose prime purpose was to look scroungy and punkish and wear beat-up leather jackers and look as obnoxious as we possibly could to adults. I look at these kids with baggy pants now and I realize that they’re doing the same thing. I hope they’re having fun. I had my fun, so why shouldn’t they have theirs?”

For a brief period, Stan even rode around on a Harley-Davidson chopper and “ran with the Galloping Gooses” (a Hell’s Angels-style Californian motorcycle club).

Any other talented young designer shown the door by GM might have looked for a new job with a more progressive car company. Not Stan. While drawing cartoons for an ad agency in New York, he met a beatnik go kart racer named Bill Davis and hatched a characteristically outlandish plan.

He decided to circumnavigate the world on a go kart—a 175cc Lambrera-engined Italkart with a top speed of 60 mph. Why? For a bet, apparently. The prize? A cup of coffee. “With sugar and cream,” Stan’s quick to point out.

Stan set out from New York on February 15, 1961 with $125 in his pocket. He arrived back in the city in June 1964, having driven 38,000 mites through 29 countries including Japan, India, Kuwait, Greece, Italy, Spain, Hungary, Poland, Switzerland, and north Africa. Quite an achievement considering its highly dodgy number plate that was a gift from “a sailor in Napoli.” In recognition of his achievement Guinness awarded him the record for go kart circumnavigation of the world and Stan got his cup of coffee.

“The go kart was a university.” says Stan. “This was seeing the world literally from the ground up. It was a wonderful, funny adventure.” The gimmick allowed Stan to hobnob with rich and poor. On one occasion he was invited to race his kart agains King Hussein of Jordan (a fellow karting enthusiast) and his wealthy sheik friends. He lost.

Fun it may have been but the trip was filled with risk and physical hardship. Stan crashed a dozen times, got thrown in jail, rode through the Sahara, ventured across the Iron Curtain, mixed with the Parisian criminal underworld, and resorted to any number of scams and hustles to keep some money coming in (“It was really educational.”).

Driving from Marseille to Geneva, he ran between the rear wheels of a truck to shelter from the icy wind. “It was freezing cold and I could stay warm and comfy if | stuck to the truck like a remora on a shark,” he explains. Did he actually attach the kart to the truck, | ask? “No! That would be ridiculous!” he resorts, “Safety first!”

“Where’s the kart now,” I ask? “Last I heard it was hanging up in a restaurant in Switzerland. I don’t get a kick out of tangible objects.”

Stan returned to Switzerland after his trip, got married to his German fashion designer wife Ise, and has lived in Lausanne for seven years. But the wanderlust returned, so the couple bought a 57-foot Turkish Gaff Ketch called the Deniz Agaci and sailed around the world for the next 17 years. By now Stan’s cartoons were appearing in some of America’s top magazines including National Lampoon under the editorship of one P.J. O’Rourke. (“Blessed be his name. He was a great Editor…he bought everything I sent in.”)

In the early ’80s Stan took a job as a DJ on a radio station in Majorca. The “Captain Stan Show” was a stream of Pythonesque consciousness weird-out which must have left baffled tourists wondering if their Watney’s Red Barrel hand been spiked. It didn’t last long,

Eventually they sold the boat and settled in Ise’s home town of Neuss, where they have lived in relative normality since ’93. “She’s another iconoclast, happily, so we two iconoclasts can keep each other company.”

He cheerfully describes himself as an “old geezer” but Stan doesn’t appear co be slowing down. He shows me sketches for a 2004 model car he’s helping to style and then begins enthusing about his biggest project to date: “a monument to the automotive age.”

“We live in an automotive age.” he says, “yet no-one has actually built anything to celebrate the thing. I find that curious.”

In a grandiose bid to address this oversight, Stan is currently trying to persuade a U.S. car manufacturer or a hotel builder to construct a giant American car, so vast you could drive a double-decker bus under it, with a restaurant and dancehall in the passenger compartment.

And Stan has another unfulfilled ambition. He wants to go into space. “The earth’s all well and good. But space is where it’s at,” he explains before launching off on another tangent encompassing space tourism, The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy and the possibility of extraterrestrial life.

Good luck to him. Captain Stan: Space Cadet. Why not? Just think of the drawings he’d bring back with him.

Visit Stan Mott’s Autobiography on Dean’s Garage. Stan wrote this exclusively for the Dean’s Garage book. The post includes a list of Dean’s Garage posts featuring Stan Mott’s work.

Also, visit Stan Mott And His “Cover Story” For The LaDawri Conquest: Road & Track, July 1957 on Undiscovered Classics.

And, for the record, we published Robert J. Lurie’s stories of the famed and infamous Pignatelli in Car and Driver with illustrations by Stan Mott.

Still looking for OEM stitching to restore a Pignatelli barn find. Apparently it ran well when parked, but some of the gears seem jammed now and the winding key is missing.

Since the availability of back issues of Road & Track and Automobile are spotty, do you think that a complete publication of Stan Mott’s work in book form could be assembled and sold to the public ?

We celebrated the 100th Anniversary of the Pignatelli with Stan 10 or so years ago. If Pebble Beach could celebrate the “birth of the Ferrari GTO” to beat us to the gate, then we could celebrate the “Pig” 48 years early.