Mitchell’s A-Body Boattail Riviera

By David Burrell (automotive writer and founder of Retroautos®)

Republished by Permission from Shannon’s Club

Photos copyright: General Motors.

There is no mistaking a 1971 Buick Riviera. It is big and emphatic. Parked or rolling, it is a flamboyant fashion statement. It was and remains one of General Motors’ design boss Bill Mitchell’s most controversial designs.

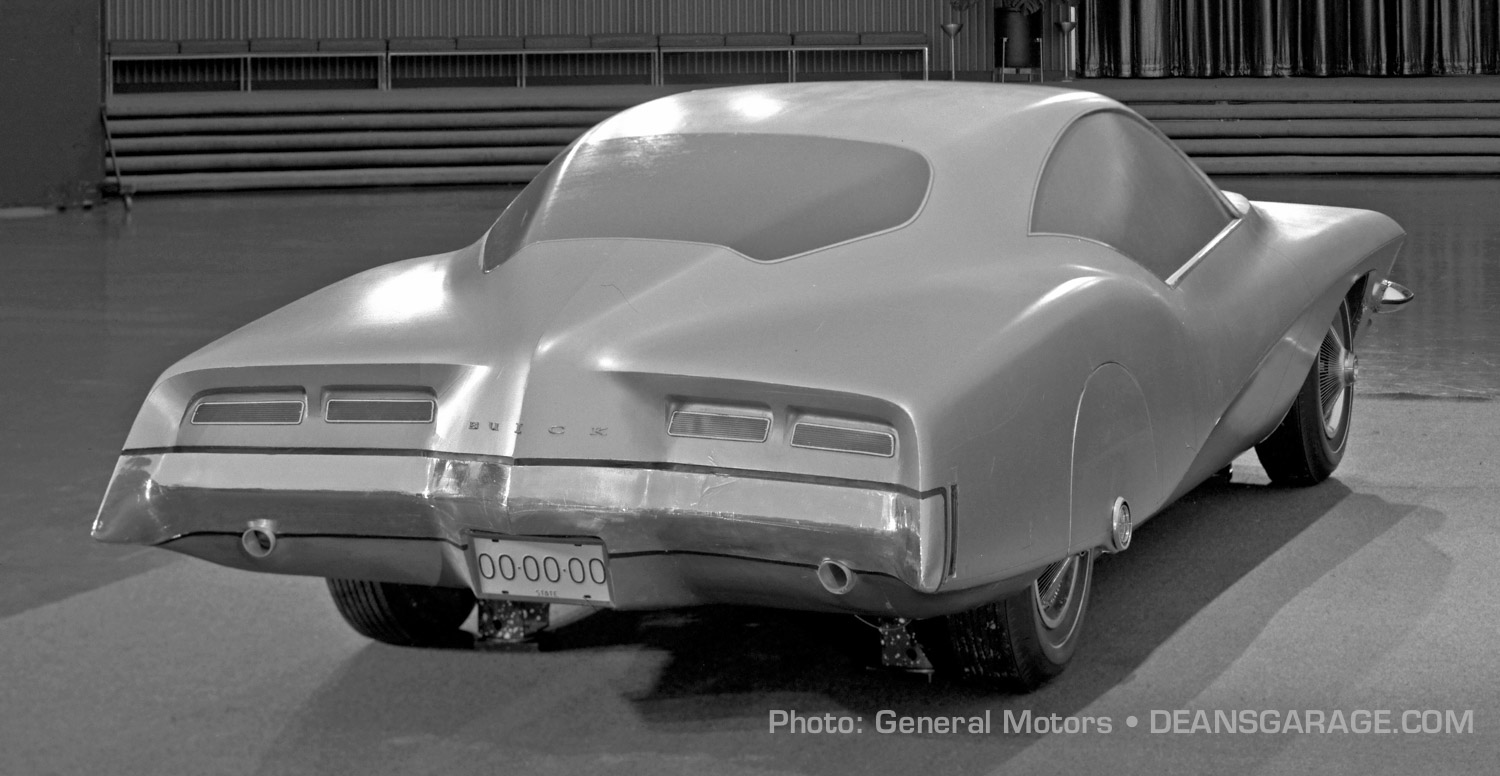

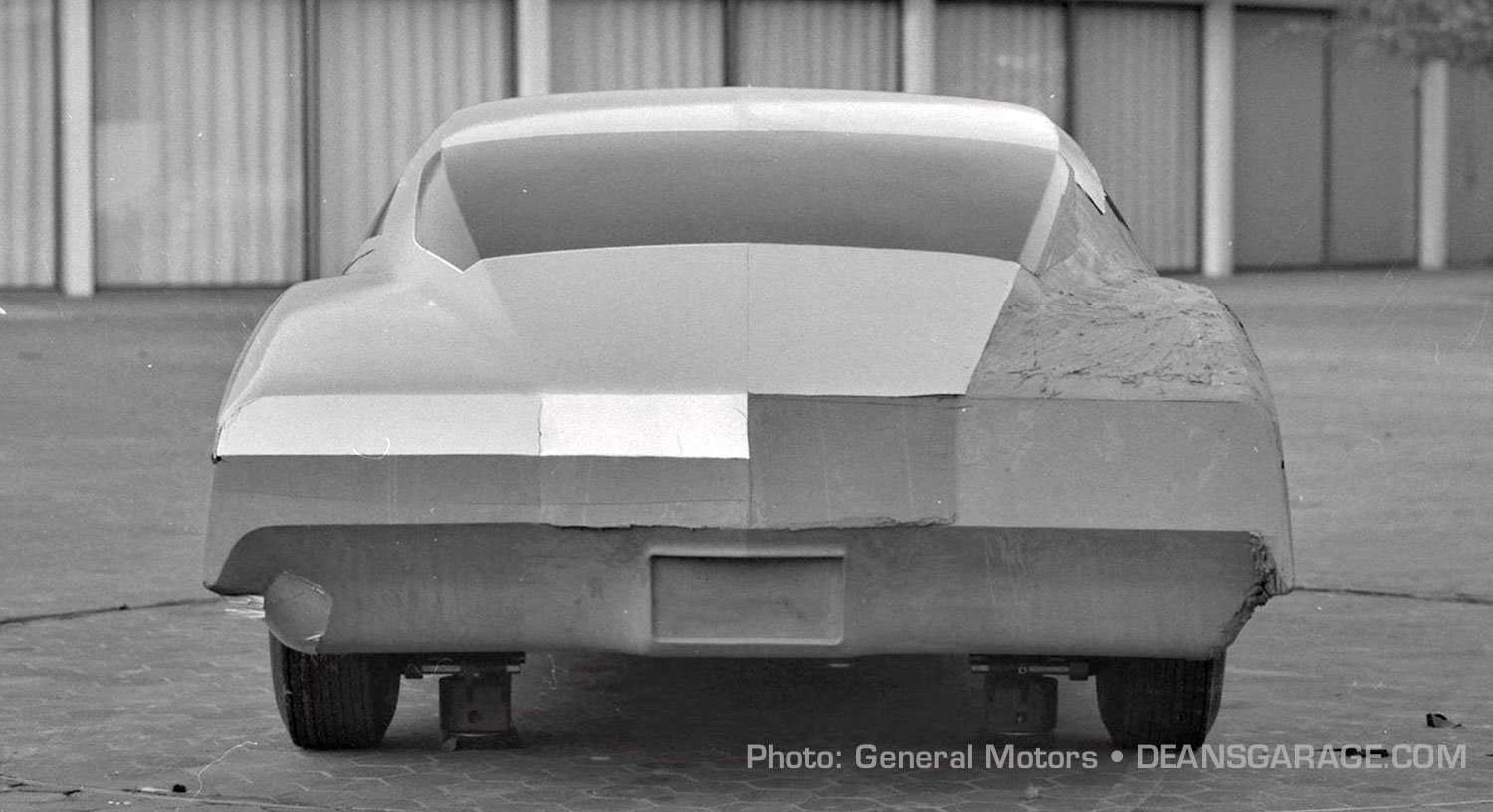

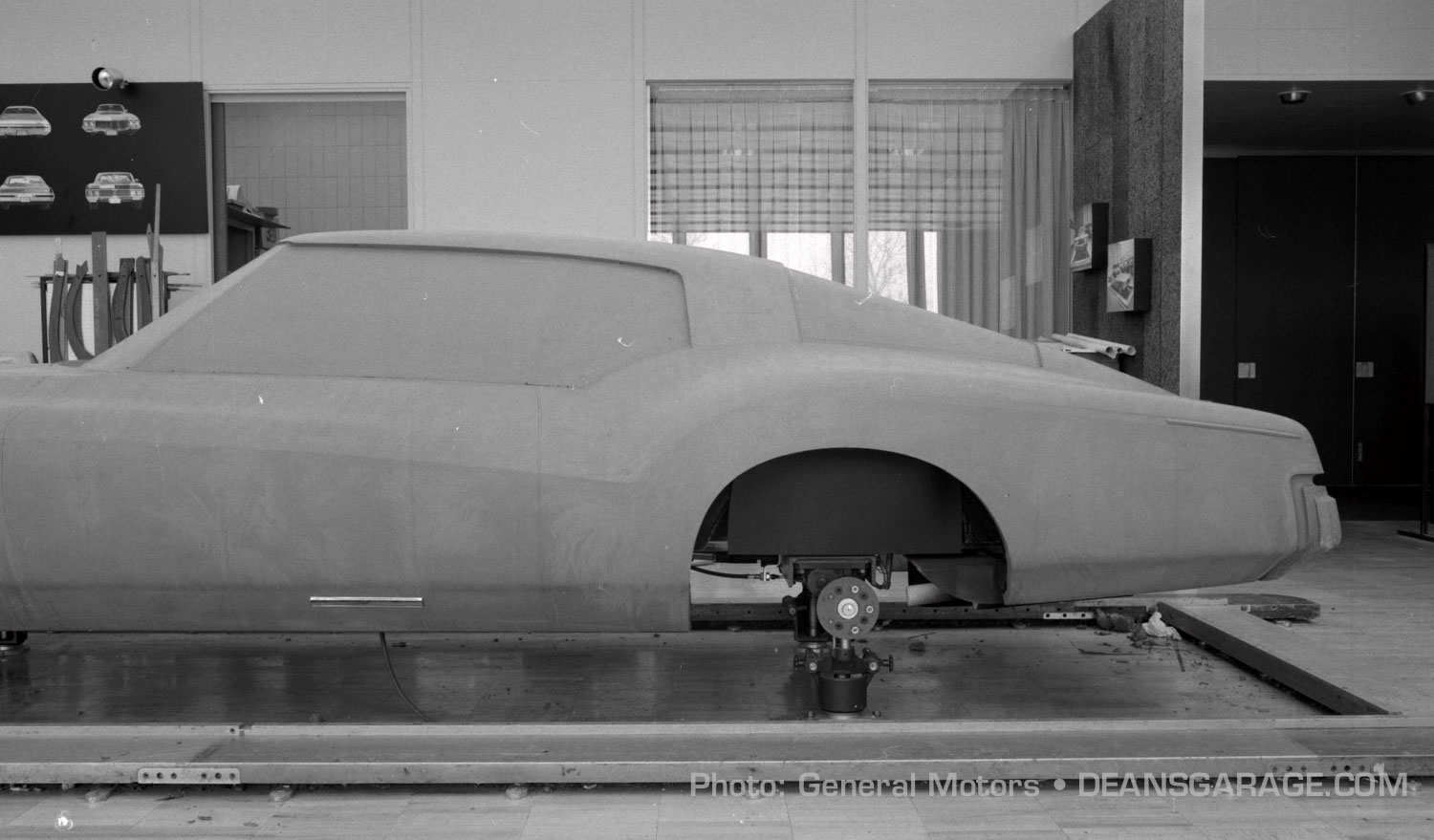

B-Body Riviera clay model—Design Staff patio.

When interviewed by Collectible Automobile in August 1990 about the Riviera, David Holls, who had styled the 1966 Riviera, said that Mitchell “felt that cars were getting kind of bland and he wanted a kind of drama in a larger car.” And Mitchell certainly delivered drama. Bland was banished from the ’71 Riviera.

Said Buick general manager Lee N. Mays in the media release at the car’s launch, “this classic new design is a triumph of automotive styling.” Privately he is reputed to have disliked the car which had been approved by his predecessor Robert Kessler. In some ways, Mays was right to be dissatisfied, because the ’71 Riviera could have been such a different car had the bean counters not demanded significant cost cuts that, paradoxically, increased the car’s dimensions and changed its shape.

Mitchell and the car’s chief designer, Jerry Hirshberg, who would go on to be the head of design for Nissan, originally intended that the Riviera be a standalone model about the same dimensions as GM’s A-body personal cars, the 1970 Chevrolet Monte Carlo, and 1969 Pontiac Grand Prix. That meant it would ride on a wheel base of around 115 inches/2921mm, similar to the Ford Thunderbird.

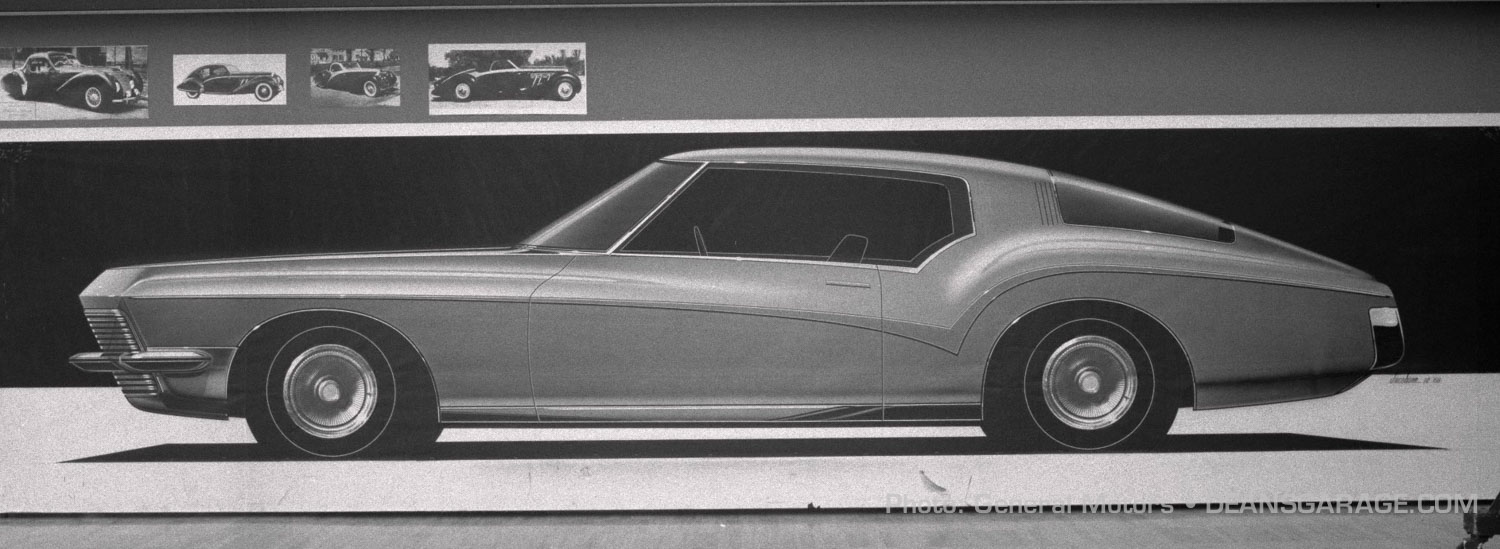

In setting the design theme Mitchell harked back to the sensuous custom cars and boat-tail speedsters of the 1920s and 1930s: cars like the 1933 Delage Aerosport coupe and Auburn Speedster. The boat-tail idea had been reprised on the 1951 La Sabre and 1956 Buick Centurion concept cars, and the 1963-67 Stingray, so Mitchell was not creating a design theme which was new. Rather, he championed a re-interpretation for the 1970s.

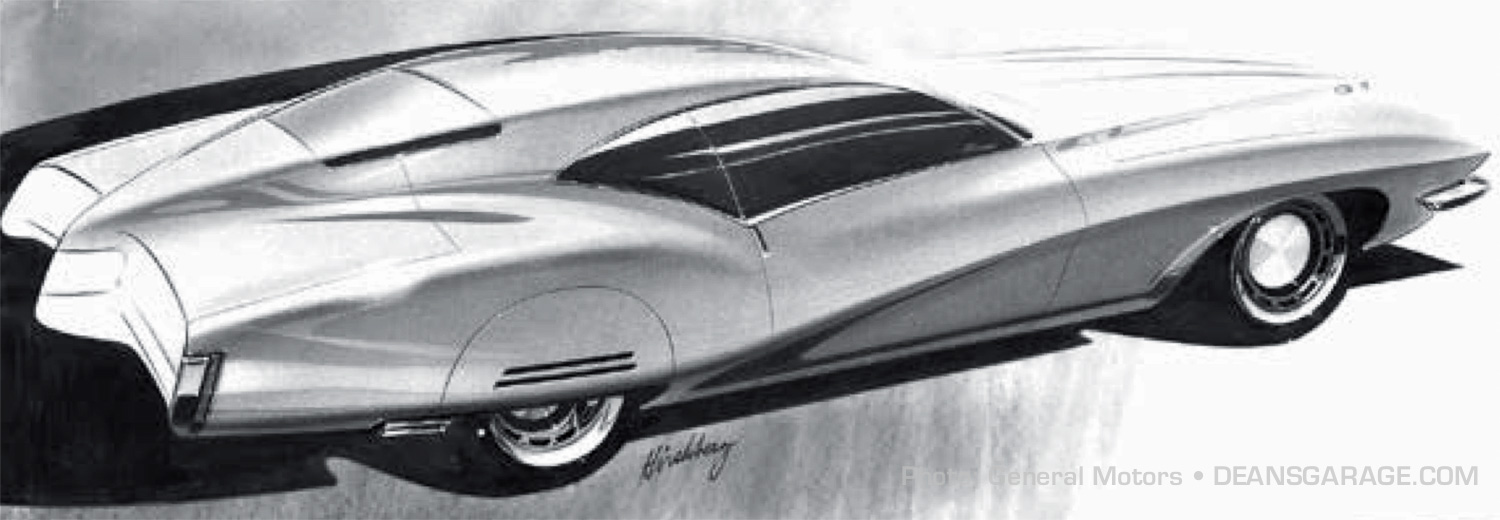

Don Deharsh was tasked with developing a 3/8-scale model of Mitchell’s vision. By March 1968 it had been developed into a full-sized clay. To say this was a striking proposal is to engage in understatement. All of the design motifs which would end up on the production car were evident in this model.

Writing in Collectible Automobile in December 1990, John Houlihan, who was one of Hirshberg’s design team, said that “our first effort under Hirshberg was a superb interpretation of Mitchell’s swashbuckling excess and the design team’s fine sense of line, form, proportion and detailing.”

Then it all got complicated.

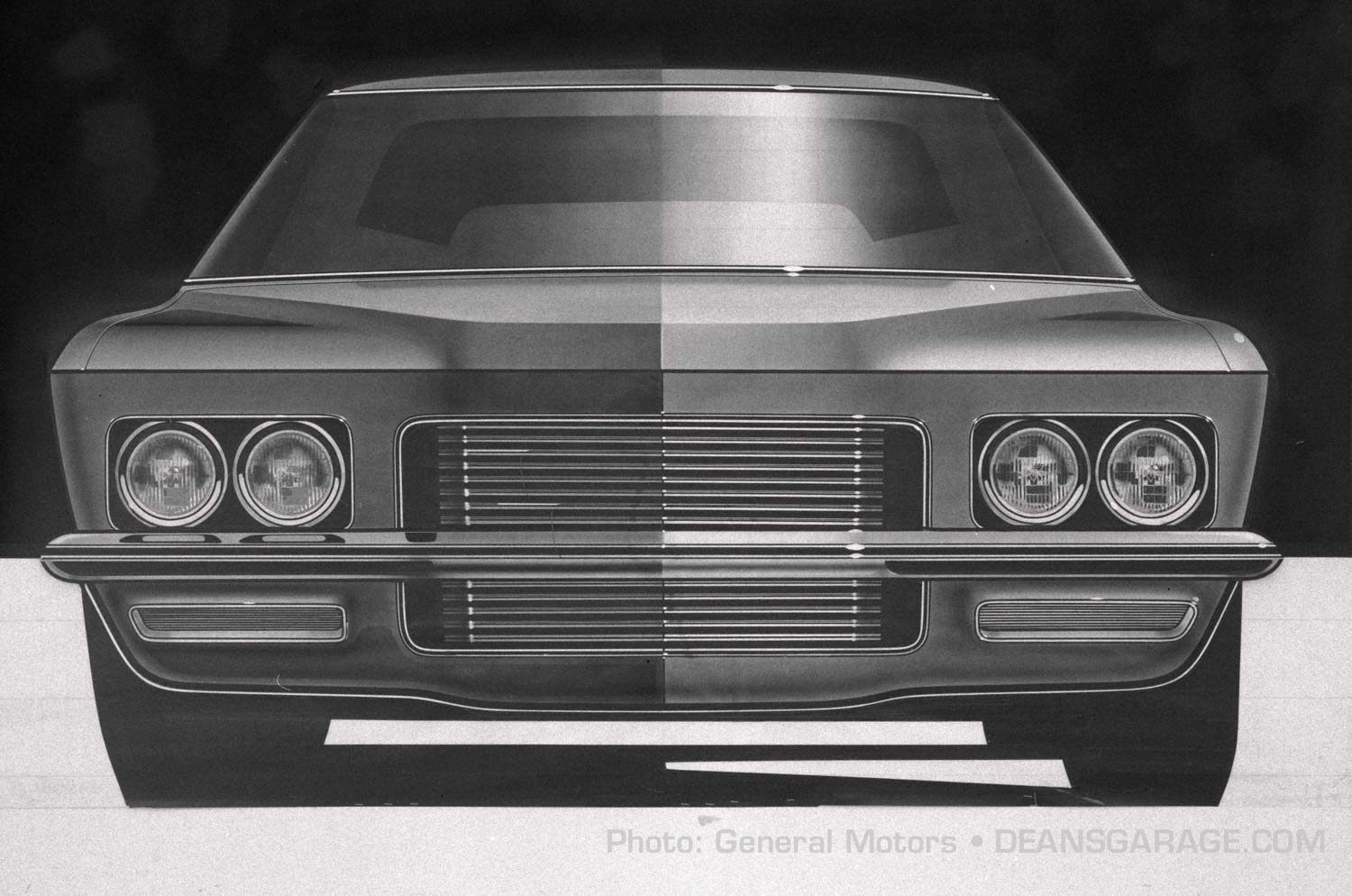

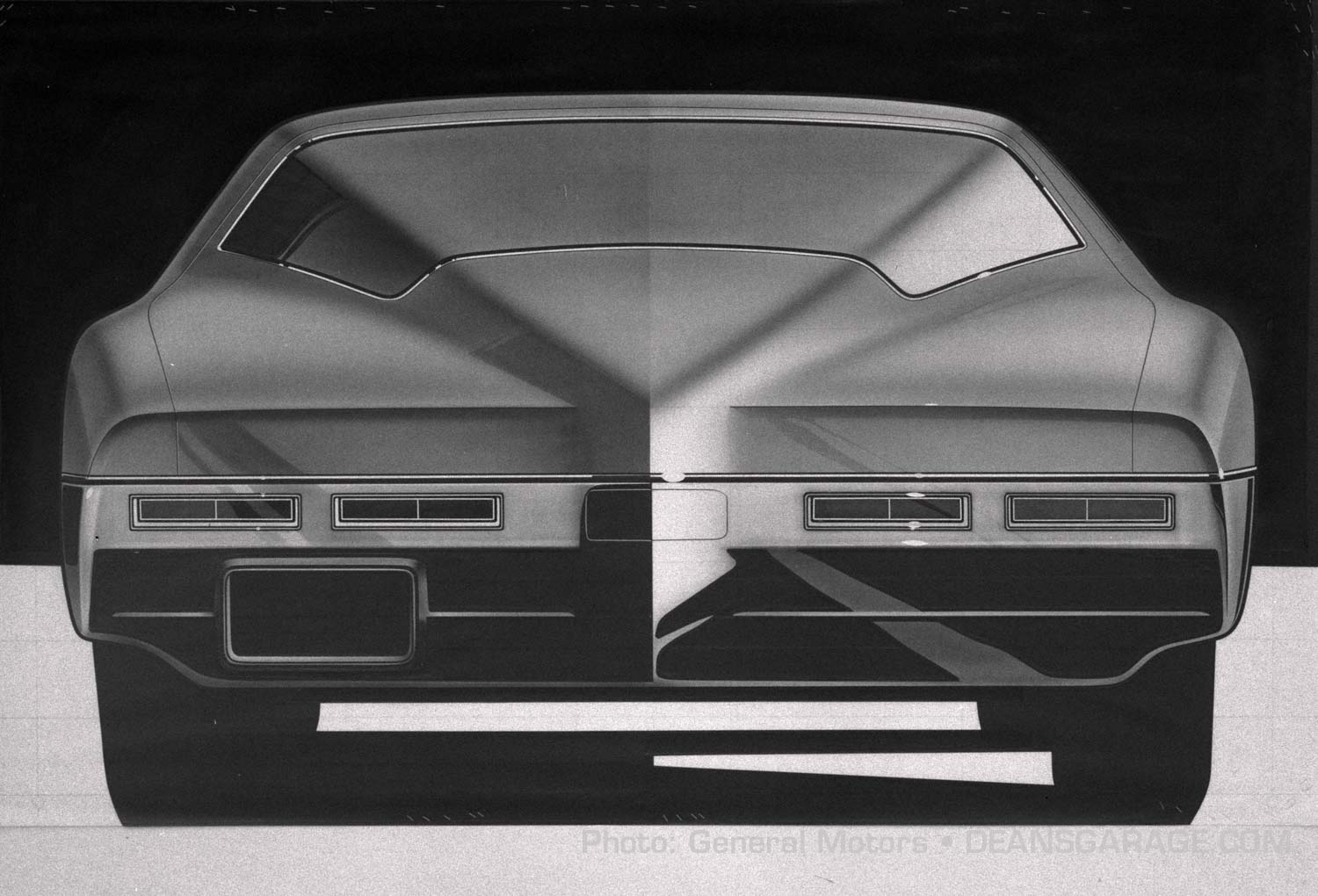

Taken in March 1968, these images capture the size and shape of what Bill Mitchell and Jerry Hirshberg had in mind for the 1971 Riviera. This is a two-sided model. The right side has wheel opening covers and a definitive sweep spear embedded in the side styling. The left side is closer to the final production car.

An alternate full-sized clay proposal was also developed which was more conservative. No boat-tail rear end.

The bean counters would not agree with the proposal for a standalone car. It was pointed out that despite the Monte Carlo and Grand Prix being prestige personal cars, GM made substantial profits because these cars shared many components with the cheaper models on which they were based. The Monte Carlo was really the Chevelle with different body panels.

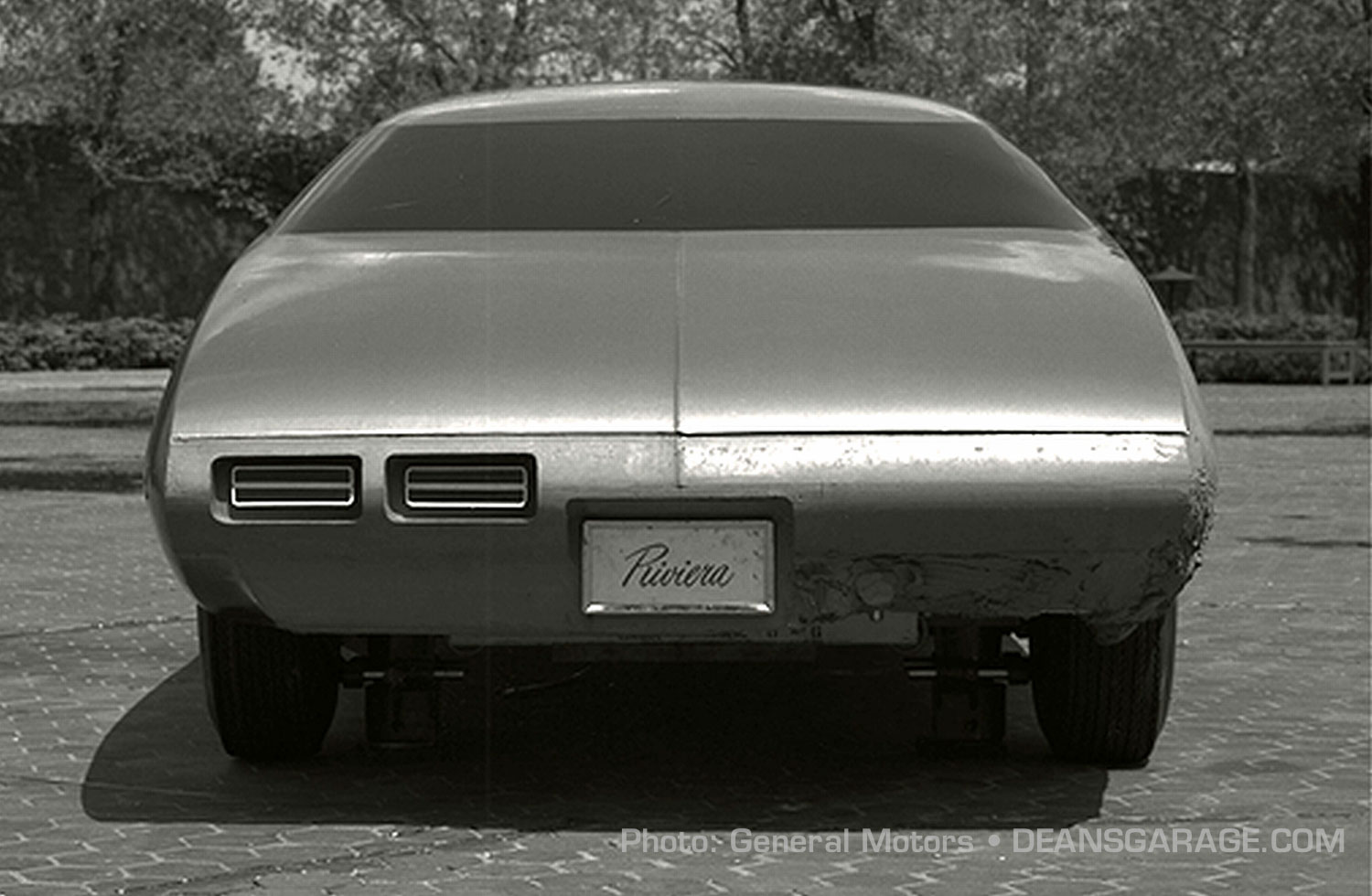

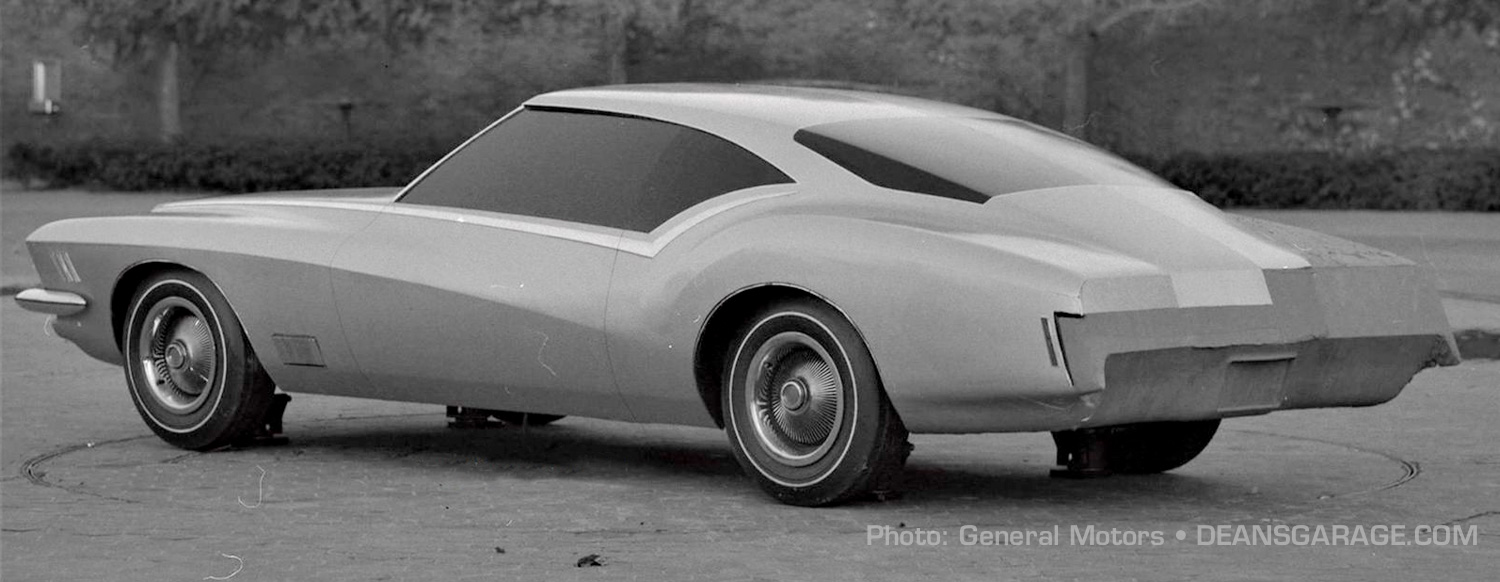

Essentially, Mitchell was told to make the Riviera styling fit around the much larger full-sized Buick chassis in order to minimize costs. That meant it had to share the chassis, cowl, front pillars, windscreen, some panels and side glass with regular Buick hardtop coupes, such as the La Sabre. Mitchell, very reluctantly, agreed. A revised theme was proposed. It did not yet feature the large wrapped rear window. The wheelbase jumped to 122 inches/3099mm. In comparison, the T-Bird was stretched across a 115-inch/2921-mm wheelbase.

At the insistence of the accountants and GM President Ed Cole, Jerry Hirshberg and his design team enlarged the Riviera onto the full-sized Buick platform. Note the small semi-wrapped back window and modest boat-tail. Clearly the transition to a larger size did not help with the proportions of the car. The transition to the exaggerated boat-tail and large rear window certainly increased the visual drama that Mitchell sought.

The cost cutting requirements meant that only the roof, rear window and boat-tail were exclusive to the Riviera. Wrote Houlihan, “this directive was a disaster—totally destroying the original concept.”

On the other hand, he added that “our design team worked tirelessly for months to convert what was once a shark into a whale, albeit a superbly detailed and proportioned one. The beautiful car you see today is a tribute to this effort and to the skill of Hirshberg and his team. I’m proud to have been a part of this slice of automotive history.” When he wrote this tribute, Houlihan was the boss of industrial design at the watch maker Timex.

Note the photos of 1930s luxury sports cars pinned to the top of this tape drawing of what became the final shape. The shape of the Riviera was controversial even among GM design staff.

Modeler Doug Cross is in the second photo.

While the final shape of the car was developing, Buick engineers were working with their glass suppliers about the manufacture of the big rear window. It required a stress line down the middle to add strength and minimise the possibility of breakage when being installed. The black car is a fully detailed fiberglass model on display on the ride road, inside of GM’s Technical Center campus, for GM Directors to evaluate immediately prior to final approval.

Mitchell is known to have spent considerable time managing the Riviera’s shape before and during the up-sizing. And he did not give up on the idea of a smaller Riviera. To make his point he staged a comparison between the upsized car and a version of the car he originally wanted. Mitchell was determined to prove his point about the Riviera needing to be smaller. He arranged this comparison of the production shape and the size he had advocated. The differences are clear.

The Riviera’s styling has overshadowed the fact that it was quite technically advanced for the era. It boasted full flow ventilation and a computerized traction control system. But the technology was not enough to convince buyers.

The styling was blamed when sales of the ‘71 Riviera did not match those of previous years, dropping nearly 10% to 33,800 and doing similar numbers in 1972 and 1973.

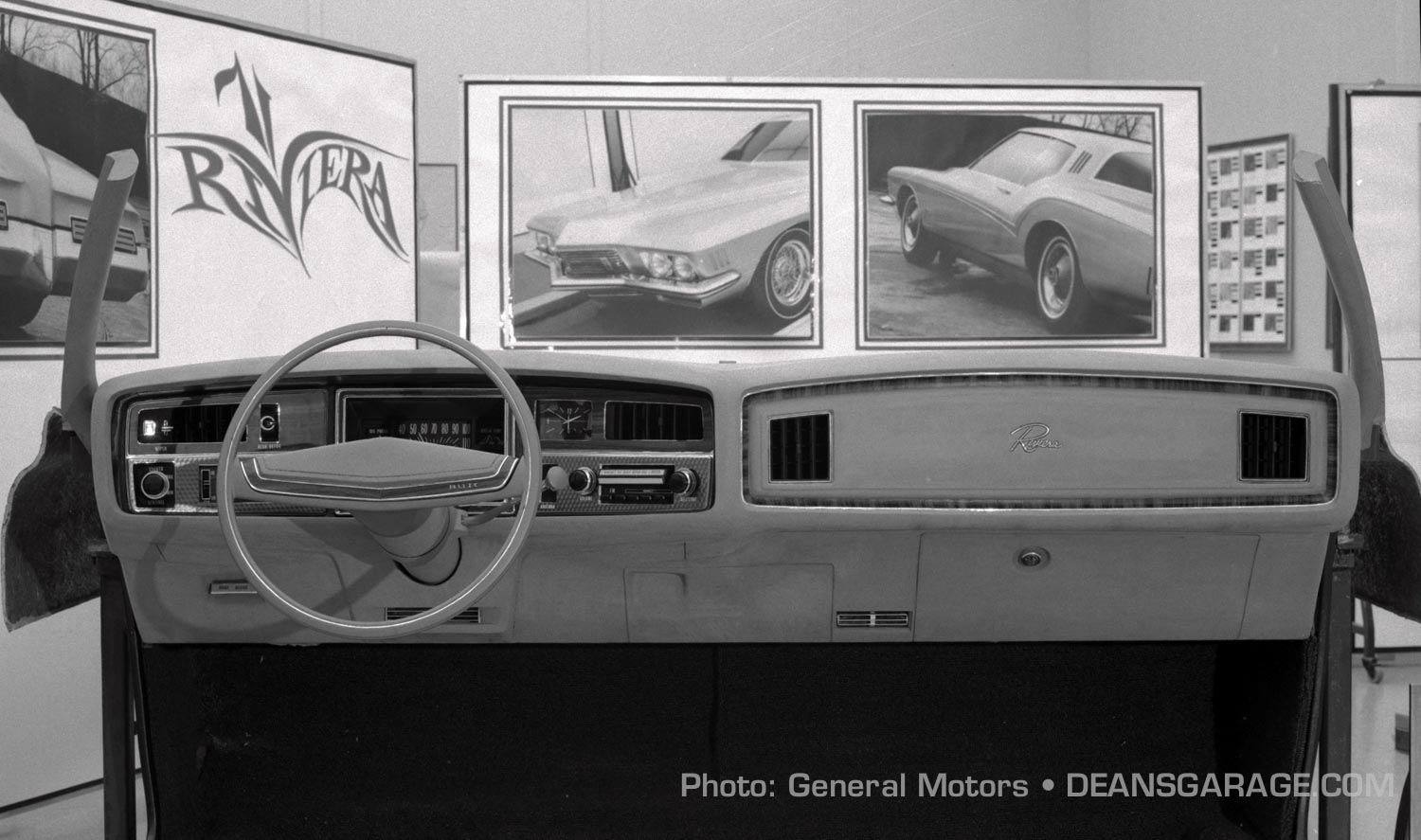

For 1971 and 1972 the Riviera boasted a unique instrument panel. Cost cutting dictated a switch to the standard Buick dashboard for 1973. The “71 Riviera” logo on the back wall incorporates the boat-tail theme.

For 1974 a completely squared-off rear end was developed eliminating all traces of the boat-tail and its glassware. Sales plummeted even more to a mere 20,000 and stayed there through 1978. So, perhaps it was the size of the car which dampened sales, not the styling. In 1979 a new, front drive, smaller Riviera was released. It sat on a 114 inch/mm wheelbase and was about the same size as Mitchell had originally envisioned for the ’71 car. Sales skyrocketed to 52,000. But by then Mitchell had retired.

So, what to make of the 1971 Riviera?

Ray Knott, founder and director of the Riviera Owners Association, says that “love it or hate it, the 1971 was a major step for Buick to design such an unusual body style. For years, the boat-tail design did not get the recognition it deserved. Now the 1971–73 Rivieras are one of the most popular Rivieras ever made. And well deserved.”

I like the ’71 model. Always have. It pushes the boundaries. If you sought anonymity in 1971 the Riviera was not the car for you. Fifty years later it still stands out.

To see the Silver Arrow III is to understand what Mitchell was seeking to achieve. That the cost cutters thwarted his dream was to the detriment of GM, not Bill Mitchell.

And what did Bill Mitchell think of the criticism? David Holls has an interesting perspective. “It wasn’t really the world coming to an end. Mitchell would have just preferred it to be slightly smaller,” he said. Holls did admit that “deep down…I’m sure it hurt him a little that it didn’t go over better than it did. But he never let me know that or anybody else…He was too proud for that.” That said, Holls added that “Bill Mitchell didn’t care what anybody said.”

A special thanks to John Kyros at GM Heritage and Ray Knott (https://www.rivowners.org/) for their advice and researching of images for this story.

David Burrell

Creation of the Boattail Riviera

by Bruce Brooks

In early 1968 I transferred from Dick Ruzzin’s Adv. Oldsmobile Studio to Jerry Hirshberg’s Adv. Buick Studio which was on the north east end of the second floor of the Design Staff Building. At that same time Doug Cross also transferred there from Chevrolet 2 Studio.

We were transferred to add to the clay modeling team that consisted of Frank Hughes, Frank Funk, Ben Vitale and Joe Henelt. Joe only worked on the 3/8-scale models. We were tasked with the sculpting of Bill Mitchell’s first design of the 1971 Boat-Tail Riviera. The clay armature was built to what were A-Body dimensions and configuration.

At that time Hirshberg’s design team consisted of Len Casillo, Jerry Palmer, Tom Hale and Joan Klatil. They all did a great job of executing special details in design direction. The engineering team consisted of Tom Krauzowicz and Mike Fylan.

Mitchell’s “Sweep Spear” design theme came the full length of the hood past the A-pillar without a break, across the door belt line to a graceful arc ending under the rear quarter window. The whole design impact of the models lines, shapes, and surfaces gave a feeling that the proportions were just right. We photographed the finished clay model in the studio with silver and black Di-Noc and foil trim late in April of 1968 for a Buick Division management concept review.

Unfortunately GM Corporate management put a change of direction in front of Mitchell to have the car done to a B-Body dimension. With great regret Bill knew that change would compromise the beauty of the car’s “Sweep Spear” design theme. That decision was a huge mistake by upper GM management and I feel that led to the cars’ short life and ultimate demise. From sleek to lead-sled—nice move.

With that new direction Casillo and Palmer transferred to other studios and Tom Hale departed GM Design. We did add John Houlihan’s design talent from Preliminary Design Studio. Our studio had to immediately start a new direction with the build of a B-Body clay armature placed in a rail located across the hall in a temporary studio next to Adv. Oldsmobile Studio. We just knew that the “Sweep Spear” theme would not be able to make it past those wide A-pillars of the B-Body armature and not have a considerable break in plan view. That theme idea ended there. We continued work on the new direction and in 1969 the armature was transferred with the remainder of our studio personnel down to our new Advanced Two Design Studio on the first floor where the old shops once were. After a short time there the 1971 B-Body Boat-Tail Riviera was sent to Buick Exterior Design Studio for a final production release.

History of the Boattail Riviera from Buick-Riveria.com

Permission to re-post requested.

The design was selected while Kessler was general manager, but Lee Mays was in charge when it was introduced. Mays publicly called it “a classic new design that is a triumph of automotive styling.” Privately, however, he hated the boattail Riviera and spent much of the rest of his Buick career trying to get rid of it. “Sure, people liked it, some people like anything,” Mays: “I could never find anyone who admitted they designed it.”

Jerry Hirshberg did. Hirshberg, later chief designer of Buick Studio 1, where the larger and intermediate Buick were designed, acknowledges that he was responsible for the Boattail Riviera, trying to interpret a concept of GM styling chief Bill Mitchell’s.

“It is a peculiar car to look back on,” says Hirshberg. “Bill Mitchell was the prime mover of the car; he wanted a classic. The boattail was my first big assignment as chief designer of advanced Buick, and I threw myself into the work.”

“At first it was supposed to be on a smaller body, the A-body. But then it was built on the B-body, and that didn’t help. On a smaller car it could have been kind of interesting. It was one of the more painful exercises I’ve ever been through. The car looked slightly eccentric. But so would a Corvette if it were the size of a Cadillac. I will say I have taken a gentle ribbing around the office about it, but the car did have aspects I like myself. Mitchell wanted a classic. And to Bill’s credit, he liked a little controversy. Too often, we are intimidated by all the regulations. But I think the boattail was a mistake.”

Ned Nickles agrees. From a styling viewpoint, the boattail Riviera, he said “was a disaster and the ones the next few years after were no good.” But there are people so fond of the cars that they carefully restore them. Kessler today says he thinks the boattail was a “nice, distinctive car” but that Buick didn’t do a good job of marketing it.

The last word goes to Mitchell, who comments: “What hurt the boattail was to widen it. It got so wide, a speedboat became a tugboat.”

I didn’t really care for the last car, the one I sawin Jerry’s studio was sensational. You just couldn’t get the shape into the big car. Everything looked long and dragged, not at all sculptural. It looked like it had been designed by carpenter.

However, about five years ago, I went to a local car show and someone had one there, it was black, and they had painted all the chrome bumpers body color. The backend of that car looks sensational. I’m not a boattail fan unless it’s a Bugatti or an Auburn Speedster. But that day on a bright sunny evening, that black car with black rear bumper was spectacular.

Great history of the development of a modern classic.

Great article. Congrats. What amazing talents both in design modeling and engineering.

Ironically as a young Designer at Ford….we had heard rumblings and back channel conversations about this so called….unheard of radical boat tail exterior design .

Bill Mitchell of course was a force and….well all of a sudden there were quite a few exterior Ford design sketches promoting a boat tail theme hah hah. Of course nothing came of these attempts but it was such a fun era in the industry at that time.

The buick boat tail is still kind of cool effort by a really talented group of automotive enthusiasts

Of course my all time favorite was Kady’s 67 eldorado and Dick Ruzzin’s Tornado.

When I first saw the ’71 my instant reaction was, ‘Oh no, a ’63 Corvette the size of a Cadillac? Ugh…’

The designers were so preoccupied with making a dramatic car, they overlooked past examples for direction. Pontiac learned the ugly dewlap rear didn’t sell when stapled onto the Grand Prix. Ford, AMC and Dodge learned quickly large fastback cars don’t sell (Rambler Marlin, 1968 Galaxie, first-generation Charger.) The writing was on the wall but no one saw it.

When the Edsel was in the design stages they envisioned it to be something so space-age and phenomenally new, they became consumed by the dream. Dave Jenkins, head of Edsel marketing, wanted the front to be – as with the Riviera – reminiscent of 1930s luxury cars, with their vertical grills. Aimed at the young executive on his way up the corporate ladder, its buyers instead were the “some people like anything” crowd Lee Mays describes above.

In the ’60s while Detroit was obsessed with annual changes, Volkswagen was busy running ads claiming their cars were so reliable, they never need changing. By Mustang’s third sales year, I was persuaded Ford had come up with a car so timeless and practical, it would never need changing. But sure enough, as Michael Lamb wrote, the first Mustang restyling became “an irrigation tube”.

The 1960’s introduction of novel cars like Riviera, Cougar, Mustang, Thunderbird and Mark III were huge hits with the public, but eventually committed to slow, torturous deaths by the 1970s due to needless styling changes.

Remember, “If it ain’t broke don’t fix it”?

Low production numbers in 1971 was also due to the 67 day UAW strike in September of 1970 which affected all of GM production.

I bought a solid black one with console two years ago. Stops traffic everyday I drive it. 300HP, no emissions control, no 5MPH bumpers. I love it.