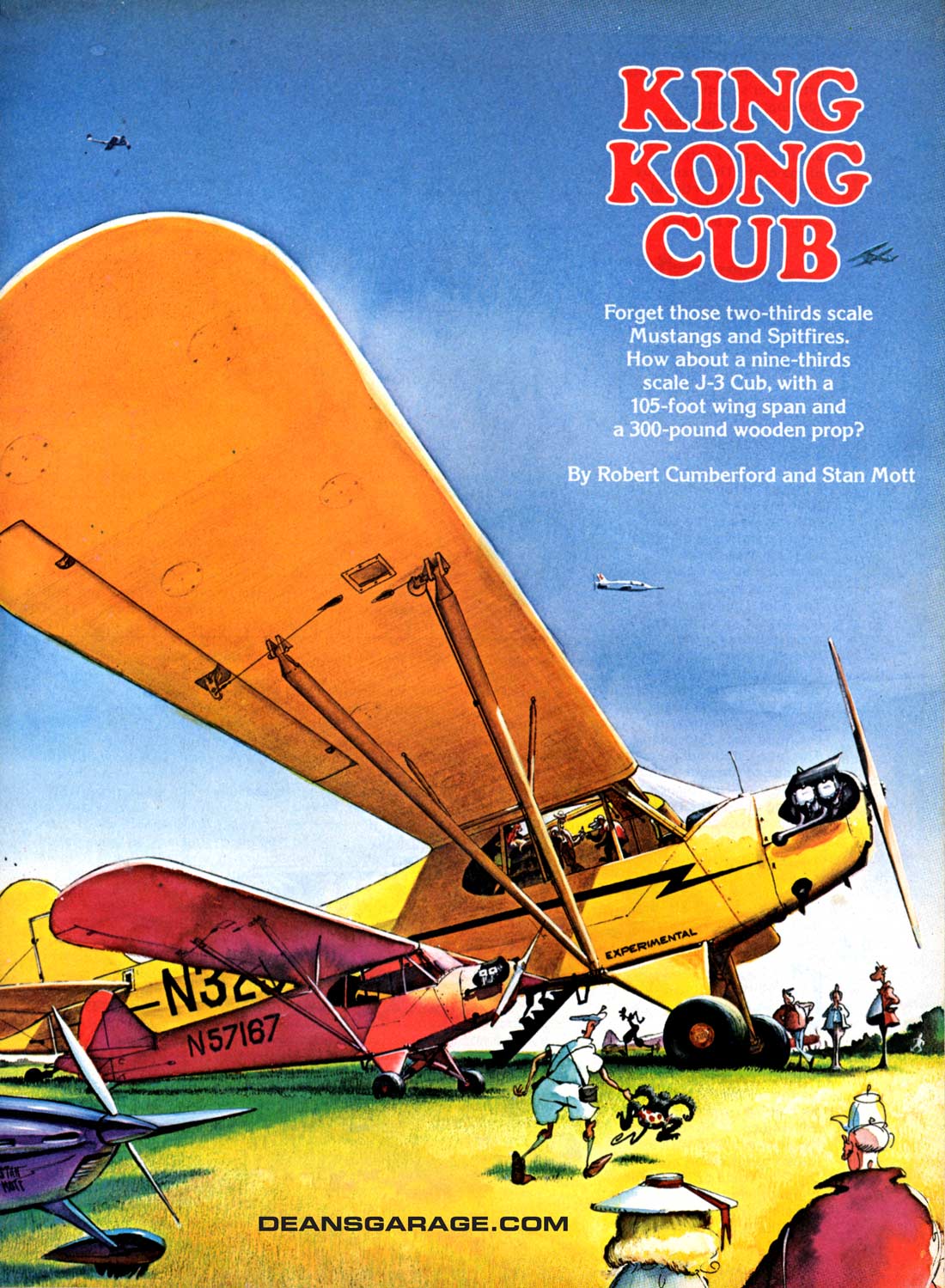

King Kong Cub

Exclusive, Mindboggling, Scaled-up Giant J-3

From Air Progress, August 1973

by Robert Cumberford and Stan Mott

Thanks to Steve Link for sending me the magazine to scan.

There has been a wonderful increase in the number of scaled-down military classics in the past few years: 3/4-size Fokkers, 2/3-size Mustangs, 5/8-size. Hawker Hurricanes. We even offered our own suggestion for a 4/10-size B-17E in the March 1972 issue of Air Progress (‘‘Hey, Buddy Wanna Build a B-172”).

But why must all aircraft always be scaled down? Aside from one or two World War-l fighter replicas that have been built to original plans, people rarely make an interesting airplane in its original size. Of course, there was the Convair janitor interviewed years ago by Bob and Ray who was building a B-36 in his basement, but he was taking home pieces of the real thing in his lunchpail, which is not at all in the spirit of homebuilding, and he never did get the FAA to let him fly it.

Why, too, must all the replica aircraft be military models? There are some exceptional civilian airplanes worthy of a homebuilder’s attention and efforts. For instance, what could be more worthy than the good old Taylor-cum-Piper Cub? Think of it! A scaled up J-3! What could be more fun to build and easier to fly?

How many times have you heard the J-3 held up as the standard to which all other aircraft should aspire with respect to handling? How many times have you heard its praises sung by the oldest, boldest aviators? Think of all the pilot reports that end by comparing the subject aircraft to a J-3. If a Howard, or a Stinson, handles “just like a big Cub,” doesn’t it stand to reason that a genuine big Cub would handle even more like a big Cub?

Of course it would! So, here are the schematic plans for the ultimate in a true family homebuilt, the J-3°—King Kong Cub.

The choice of size was easy. If you accept that a normal J-3 is not quite wide enough for one person, it follows that a twice-larger version is still only about one-and-a-half people wide—not a great improvement. But when you get to thrice-sizing, ah, there you’ve got something. There is plenty of room for two comfortable side-by-side seats, with a nice little aisle between them for the hostess to use when she’s serving coffee, and for the passengers to use on the way to the rest room. Triple-sized, the J-3 fuselage is amply high for strolling about, and yet the overall air frame is not unreasonably large—the span is only 10 feet more than a DC-3.

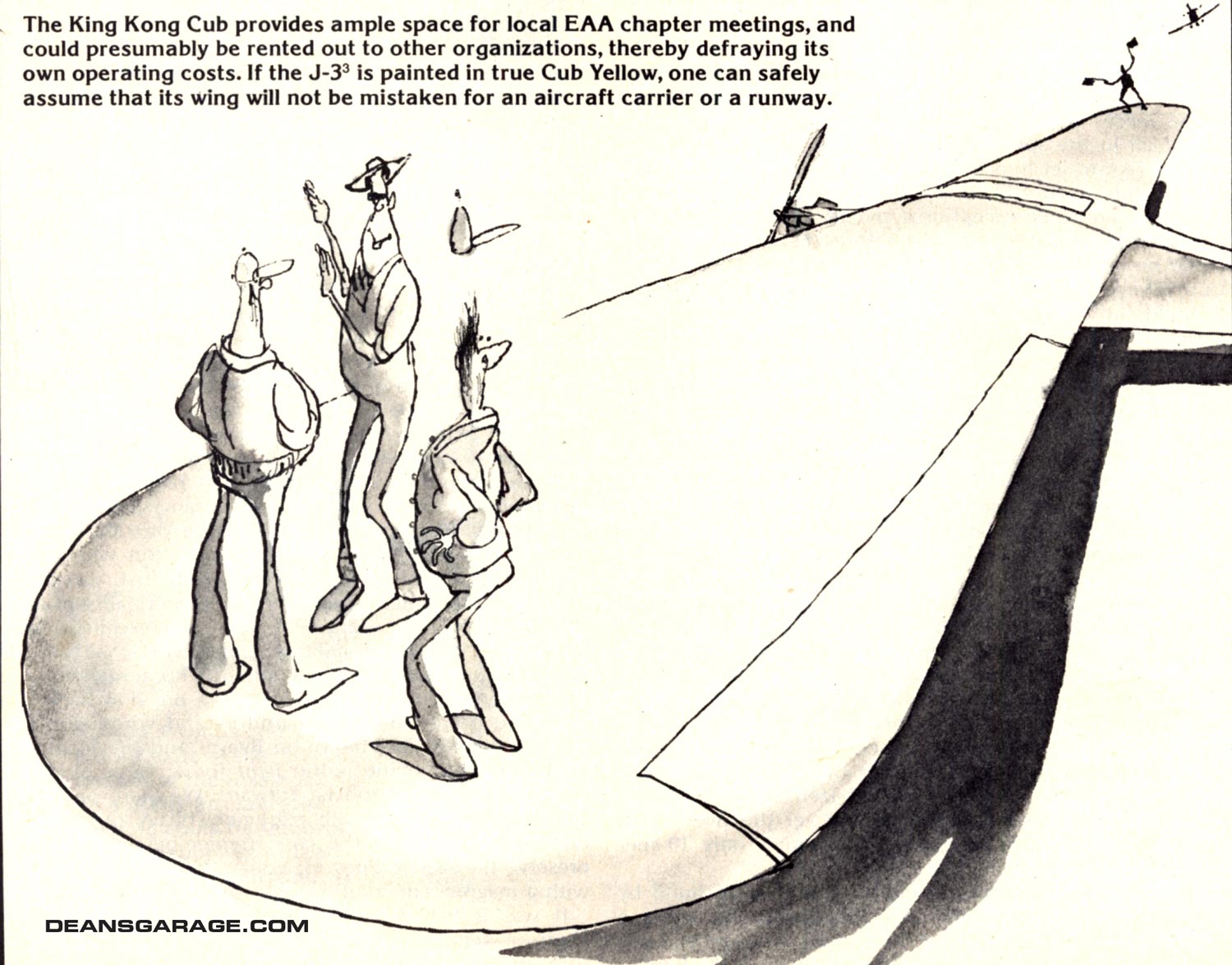

Sure, it’s big…maybe too big for one man to build by himself, but what a wonderful group project! An airplane that would occupy an entire EAA chapter for months, even years, and yet could be flown by anyone in that chapter.

Even better, it could be flown with every chapter member in the airplane. Try that with a Baby Ace!

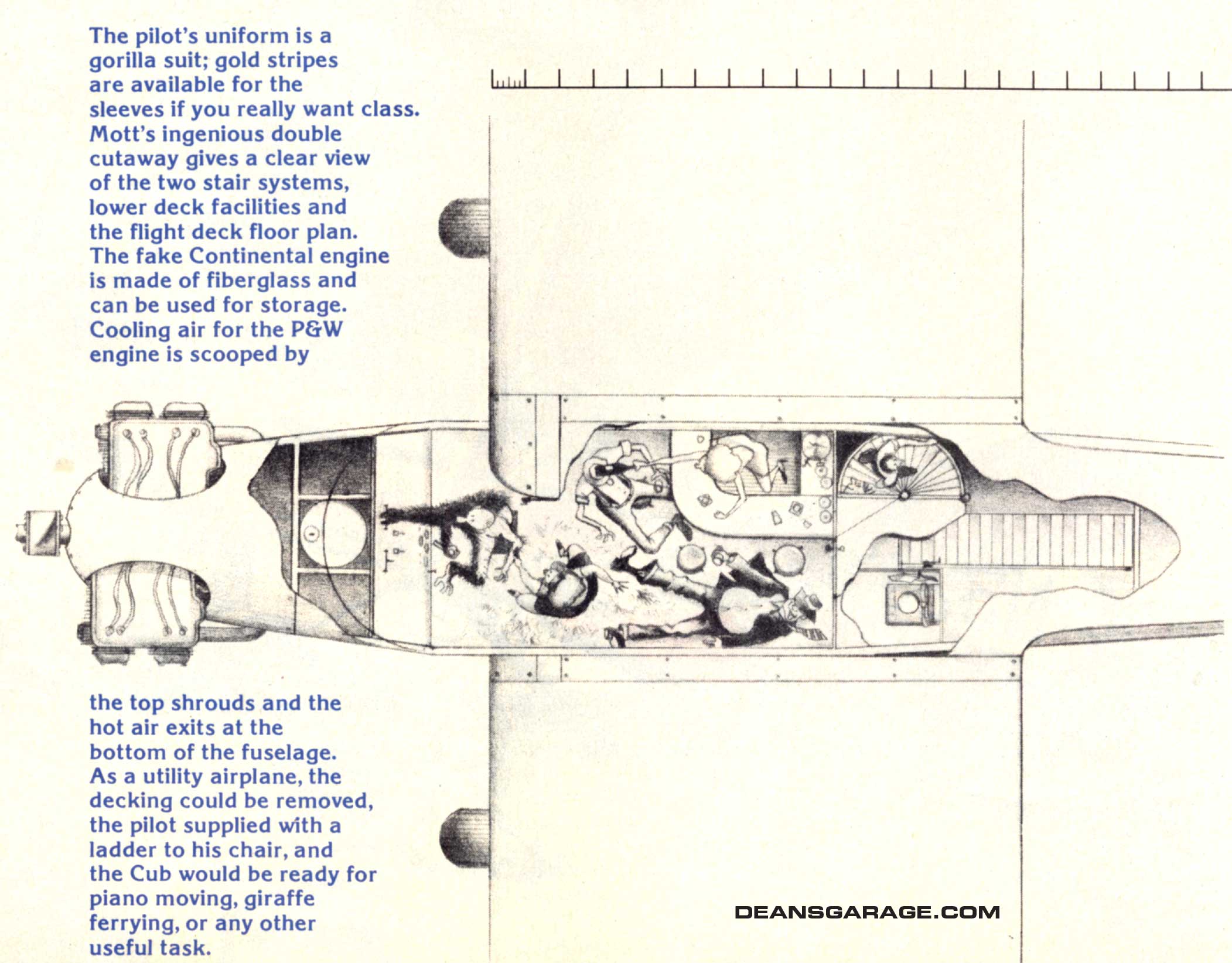

When you increase the linear dimensions, areas go up by the square, so that the wing area is nine times as great as the standard airplane’s. Sixteen-hundred-plus square feet of area is like a small house, so we’ve decided that the wing construction should be a little different from the normal J-3’s. By using plywood to cover the wing, you eliminate expensive (in this size, very expensive) drag-bracing wires and gain a splendid walkway, which is also a nice place to hold chapter meetings when the weather is good.

Since we don’t want to lose that good old Cub feel, the wing loading must remain just as it is on the normal airplane, around 6.8 pounds per square foot. This gives us a maximum permissible gross weight of 10,924.2 pounds. For simplicity, we can round it off to 10,900—just under ive tons, well within the FAA’s 12,500-pound limit for light planes. To put the wing performance into proportion, recall that the L-1049 H Lockheed Constellation, with a wing about the same size, carried 85 pounds per foot.

Of course, the Connie had Fowler flaps and other fancy devices that you do not need with a USA 35B airfoil, but its weight defeats it when real grassroots flying is to be done. Our J-3 will get off at full gross and charge over a 50-foot obstacle in only 375 feet.

Naturally, you’ve got to have quite a bit of power to handle an airplane nine times heavier than a J-3, even if all you want to do is maintain the standard power loading of 18.8 pounds per horsepower. And that presented us with a real problem. There just aren’t too many good engines in the 600-hp class (9 x 65hp = 585). Rare old Ranger V-12s would fit inside the cowling, of course. But where would you find one? The answer, it seemed at first, was to look to the most modern and efficient powerplants available, the miniature turboprops that give such excellent service in a wide variety of military and business aircraft. The Garrett/AiResearch TPE-331, with 610 hp for takeoff, recommended itself, but it did suffer a big drawback—aside from the price—that you’ll understand when you think about airplanes like the Turbo Beaver and the Pilatus Tur-bo Porter: the engine is too light for a classic airplane. It has to be mounted too far forward. We were planning to compensate for that with extremely heavy dummy cylinders on the sides of the cowl (remember, we wanted to preserve the classic lines for you), when the EAA came up with a magnificent solution, as it so often does.

It was a 1939 J-3 that appeared at the 1972 Oshkosh Fly-In, a genuine stock Piper with a radial engine! To be sure, the Lenape Papoose was only a three-cylinder radial, and it had only 50 bhp, but the principle was established: a chunkety radial engine sound is legitimate for a J-3.

You can take your choice of powerplants, but we chose the P&W R-1340 with a slight lowering of the thrust line to fit it all inside the cowling. There are literally hundreds of them around, they don’t cost too much, and you could make use of most of the power section of a T-6. Of course that skimpy little Hamilton Standard metal prop would have to go, to be replaced by a nice fixed-pitch wooden one, but that shouldn’t bother you. Props like that were good enough for the first Spitfires, after all. And wood is fatigue proof. NASA used to have some 35-foot, 5-inch metal props in their full-scale wind tunnel at Langley, but they changed to wood 30-odd years ago, and haven’t had a moment’s trouble since. Of course, you’d have to have another gear box to keep the prop under 1100 revs.

A stock 1946 J-3, brand-new, very clean, with a well- tuned Continental C-65 pushed to its limits could manage a maximum speed of 83 mph and a 73 mph cruise. Its rate of climb was 450 fpm, and it could go as far as 200 miles in no-wind, no-reserve-fuel conditions. Our airplane should be somewhat better. With a top speed of 105, we look for a cruise speed around 95 mph, with a slight edge on power, we’re looking for 750-fpm initial climb, and we think we’d hold on to that rate pretty well. But the big Cub won’t have much more ceiling than a little one. At around 12,000 feet, you may as well level off and enjoy the fresh air. One place we lose in performance is in stall speed. A stock J-3 lets go at 38 mph, the J-3* just under 45. That’s not bad, and if you had to hang on longer, you could open up the throttle a bit. We’ve cut down on fuel capacity, proportionately, in order to hold the range to not much more than 200 miles, just like a normal Cub.

Tires for an airplane like this could be a problem. Most big, big airplane tires are high-pressure, rather narrow jobs, not meant for the rigors of grass field work. There is an answer, though: Goodyear’s big baggy Terra tires, a group of low-ground pressure terrestrial vehicle wear (closely related to the original Airwheels). You might have some trouble getting the size you want without earthmover treads, but there is a Trail-Rib design that looks just right. And they weigh only about 170 pounds apiece.

Brakes, of course, have to be cranky mechanically, unsound types, operated by little buttons under your heels. Best bet here is to get some old Ford car brakes and convert them to hydraulic operation, using cylinders carefully chosen to reduce mechanical advantage and give you true J-3 stopping power—practically nil.

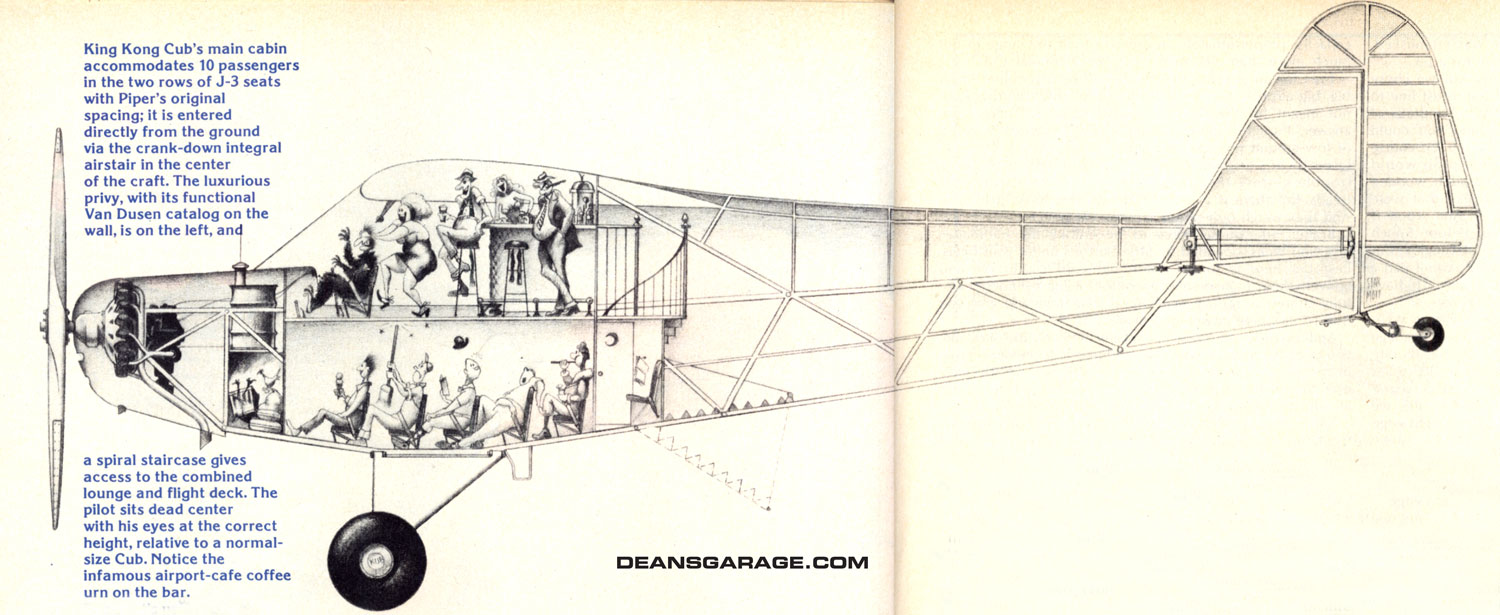

And in order to savor the classic feel of the airplane, you’re going to want to be as cramped and uncomfortable in the pilot’s seat of the big J-3 as you were in the little one. Mount the seat too close to the pedals and leave out all adjustment, so things will seem perfectly familiar.

Since you wouldn’t want to forego the pleasure of reaching up and behind you to crank trim, we’ve moved the pilot’s position up into the windshield area. True, you get a most un-Piper-like view, but you can still grapple backwards for trim, and that’s what counts.

In the main cabin, things will be at once perfectly familiar and very strange, because of scale effects. The 10 passenger seats will all be uncomfortable J-3 front semi-buckets, complete with that dark, dirty red upholstery we all know and love. The familiar oily plywood floor, scarred by a thousand muddy boots, will simply be larger and thicker. To obtain the proper effect, this floorboarding should be used in the shop during the entire construction program. Passengers on the right hand side, on nice days, can enjoy the pleasure of flight with the door hanging open and the window hung up under the wing. Greasy old cotton helmets should be stuffed in the seat-back pockets to be used at these times.

The visible structural tubing in the fuselage will be more than two inches in diameter, but otherwise the familiar sickly yellow-green zinc-chromate finish will set off the mottled inner surface of the fabric covering.

Oh, yes, the entire airplane will still be fabric-covered, even the plywood-paneled wing surfaces. Grade A cotton would be the most authentic, but in view of the incredible job covering this much surface is going to be, we recommend Ceconite covering. There is no need to discuss the color of the finish: Cub Yellow, with a black stripe.

Since this will be primarily a local-flying airplane, not much attention need be paid to baggage accommodation. There’s a fair amount of room under the gas tank. Suitcases can be put against the firewall for trips to Oshkosh or local fly-ins. A couple of light tents, a few ropes and other equipment could be stuffed into the wings from within the cabin. After all, the wings are more than two-feet thick.

Construction is fairly straightforward, with no surprises and no problems beyond those associated with handling very large, heavy chunks of material. The wing spar is not quite as big a problem as you might think. As a simple, strut-braced airplane, the Cub has no need of continuous Spars, tip to tip, and although a half-wing panel is about as big as the largest ordinary homebuilt’s entire wing, an enthusiastic and ingenious group can manage. Getting a piece of aircraft-grade Sitka spruce big enough for a solid spar might be a problem, but you could make a ply-web, four-flange spar with laminated flanges. That way, the pieces of wood are not so heavy.

And if the whole wing daunts you too much, there’s a practical solution. You can leave out the inner bay: 10 feet, 1 inches on each side of the wing, cutting the span down to a mere 85 feet 4 inches—a triple-size clipped-wing Cub. You’d have a fine “little” aerobatic machine.

The fuselage construction is probably simpler than a regular J-3’s. The tubes are bigger, the joints are easier to see, and the welding, if it takes longer, is still less difficult. The same is true of the welded-up tail feathers. Everything is easier to handle when it is big enough to see and get hold of. We’ve suggested putting a few more ribs in to keep fabric spans down, but you could do some ply covering here, too, in which case you’d stick to standard spacing.

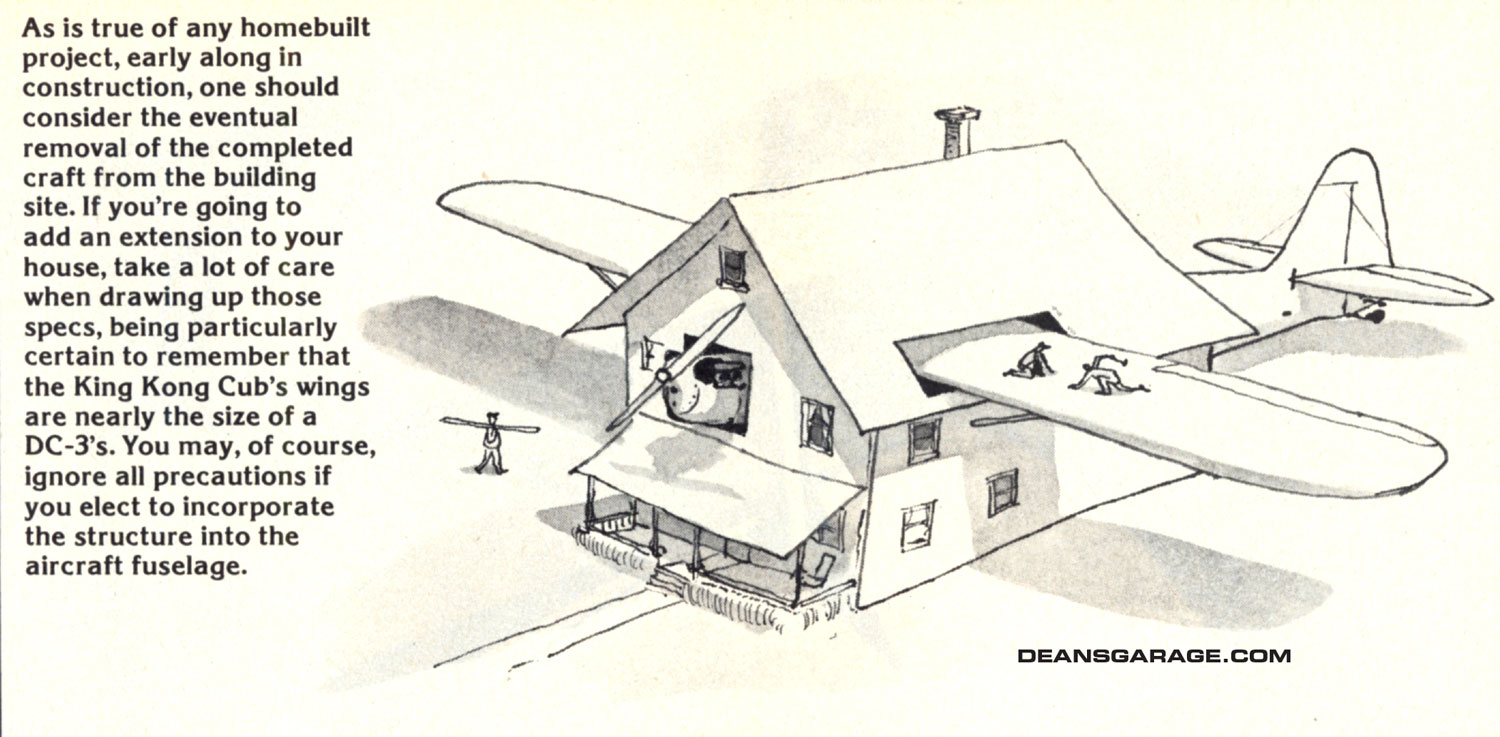

When you get to thinking about it, you can see how much easier it is to build a big airplane than a small one. You’re working with hefty chunks of stock, substantial pieces a man can really get a grasp on. You can use a whole range of tools you’ve already got around the house: pipe wrenches, big hammers, large screwdrivers—things you’ve never considered for aircraft work before. You may have to sell your station wagon and buy a moderate-size truck to carry parts in, but you’ll need the truck, anyway, to tow the rig out to the airport. And it’ll be handy for hauling in the lumber you’ll need for the extension to your house.

You’ll farm out some jobs. For instance, only a sail loft is likely to have the space and the proper sewing machines for running up a set of covering bags, and since they’ll be totally familiar with Dacron materials, they’re your best bet anyway. And they probably won’t charge much more than three times the cost of a 1946 Cub.

Ah, yes, costs. A 1946 J-3 could be had for $2,195. Today, a good one is likely to go for $3,000. So, if 12 members of your EAA chapter each invested in a Cub, there would be a total outlay of $36,000, you’d face a monthly tiedown cost of maybe $180 to $240, you’d use more than 50 gallons of fuel an hour if you all flew at once, and all you’d have would be a flock of commonplace airplanes.

That $36,000 should be far more than you’ll need to spend on a King Kong Cub, even if you buy a freshly-over-hauled P&W (and remember these engines go 2,000 hours between overhauls), and any airport operator will pay you to tie down at his field (provided your ropes are strong—can you imagine what this airplane would do if it got loose?), just for the attraction. At Oshkosh, you will ‘be able to sell rides all day long.

After all, it’s just about the perfect airplane. It combines classic light plane design with classic airline engine reliability, strength with simplicity. It’s an airplane that the whole gang can enjoy together. Best of all, it’ll fly just like a…

© DeansGarage.com, 2009–2022. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or the original copyright owner(s) is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to DeansGarage.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

LOL!!!! So good to see this posted on your site and being shared with all! This is a side of Stans art I have always loved. What a great Christmas present! The best of the season to you and all who frequent this site!!!!!

Tailwinds, Steve.

What a great story, Thanks for posting this.

Happy Holidays !

As a flight instructor, commercial pilot, and Emil Zowada’s #2 son; I wholeheartedly approve! I’ll start scrounging for oversize 4130 tubing.

Thank you for sharing this!

I knew about Stan’s crazy cars from Road & Track but not about this. What a pleasure to have a “fresh” MOtt product after all these years!

The Spruce Goose would have made more sense. LOL

What a great concept. One side effect of the relative scale of a project like this is that, in flight, its dimensions would not be apparent so that it would appear to be flying over at 2/3 LOWER altitude than it was ACTUALLY FLYING; low-altitude flyovers could have a potentially HILARIOUS effect as the plane approached the viewer.

Both Robert and Stan have (Robert) and had (the late Stan) a fabulous sense of humor to match their artistic talent. Creators of the iconic Cyclops, among many others.

A true Christmas treat blast from the past!! It is always great to see these two (some what warped) minds at work creating such fantastic concepts.

Here’s the same concept actually applied to a VW Beetle convertible. If it doesn’t link, just copy and paste in your search.

https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x8h32ho