The Changing Shape in Cars

A case in point: GM’s Design for a $1,000 car!

From Motor Life, August, 1960

There hasn’t been a car with a price tag like this from one of our major auto makers since the OPA went out of business. But the idea isn’t dead. Not very many months ago, within the sacred precincts of a Technical Center at Warren, Michigan, just such a radical machine was being born. This is a report of what happened. And why.

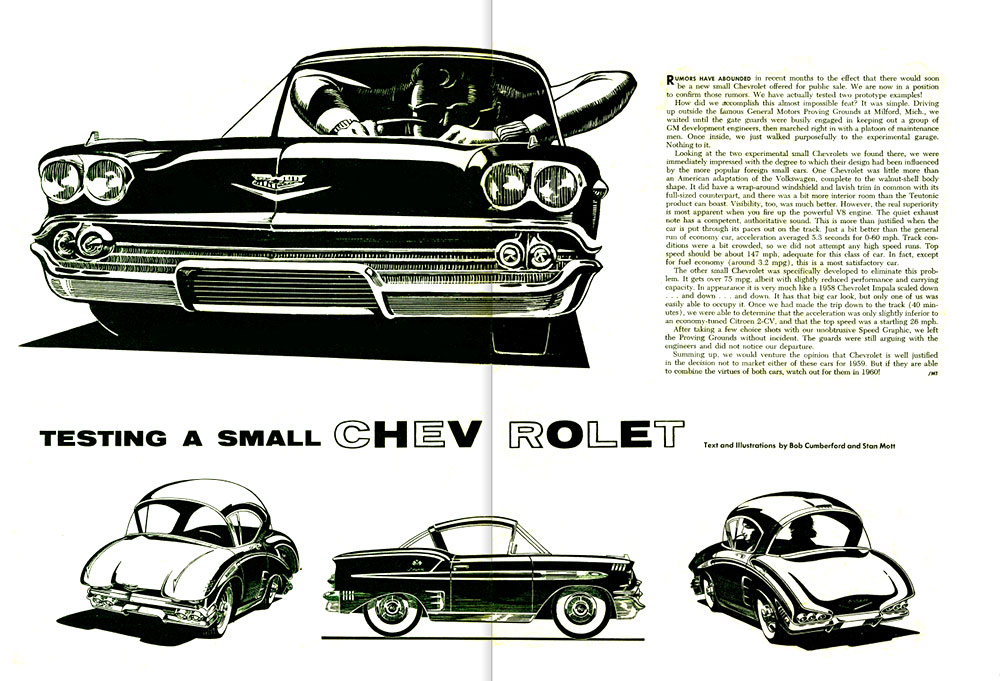

Will there ever be an American-made mass-produced super-small car—one that would deliver for, say, $1,000? If anyone does know the answer to this question, they have not been talking for the record. Yet it is encouraging to discover, amid all this speculation about the smaller cars to come from Detroit, that one auto maker at least has looked into the possibility of a truly small and economical vehicle. Shown here are sketches of the project at General Motors and on the following pages is ex-GM Stylist Pete Brock’s account of its short career. As far as is known, this protect was only a study. No steps, during the period covered by available information, were made toward production. Whether it still is on the shelf, or is again active, cannot even be guessed at this time. One point needs clarification here. The unofficial name for this project car was the “Cadet,” a name identical to another smaller-cat development undertaken, but never realized, by GM more than a decade age. The two Cadets, of course, were unrelated except in name.

How the Cadet was Created

By Peter Brock

Photos: General Motors

The XP-79. as the car was designated, began as my set of proposal sketches for possible new produce in the General Motor’s line. The occasion was an exhibit at a show for the board of directors. A short time earlier, the styling center management had announced that such proposals would be accepted and studied by a design committee.

The exhibit was held under the large stainless dome that houses the auditorium at GM’s multi-million-dollar Technical Center, in Warren, Michigan. Hundreds of ideas were on display, ranging from minor interior detail suggests to complete flying cars.

Several days after the show, the preliminary design committee chose the most promising for further consideration—and the car to be called the “Cadet” was among them. A few more days of sorting and evaluation in the chain of command and the sketches were returned to me for further detailing and polishing.

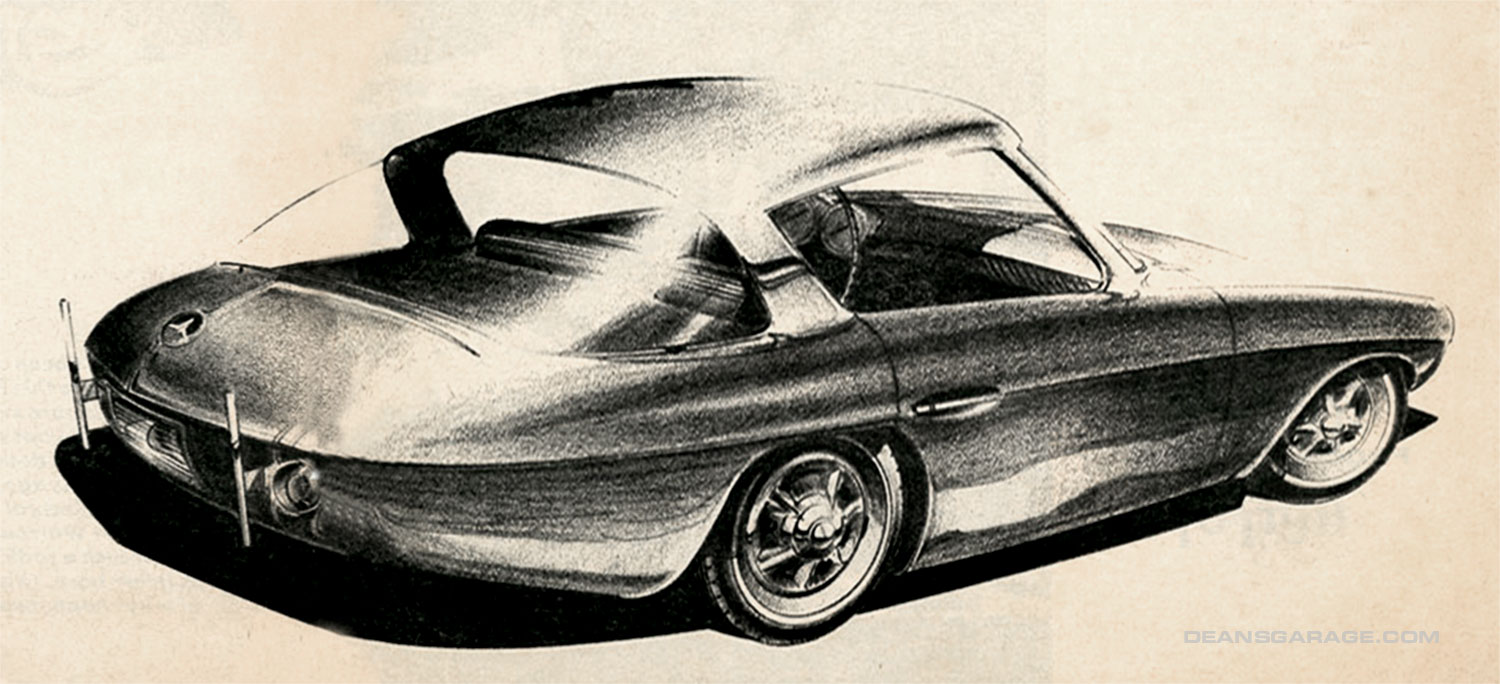

Very soon, after I had made a full-size drawing, Harley j. Earl, at that time the chief of styling for GM, appeared and made his analysis. He really took it to pieces. I had designed the car with a front entry and much glass area. The entry, Earle thought, was impractical, and the excessive glass area would be too costly. I probably was visibly shaken. Although Earle was often dictatorial, he did pride himself on encouraging new ideas, so after he left, I was advised by one of his assistants that the glass area should be modified and conventional doors incorporated. Then Earle would look at it again.

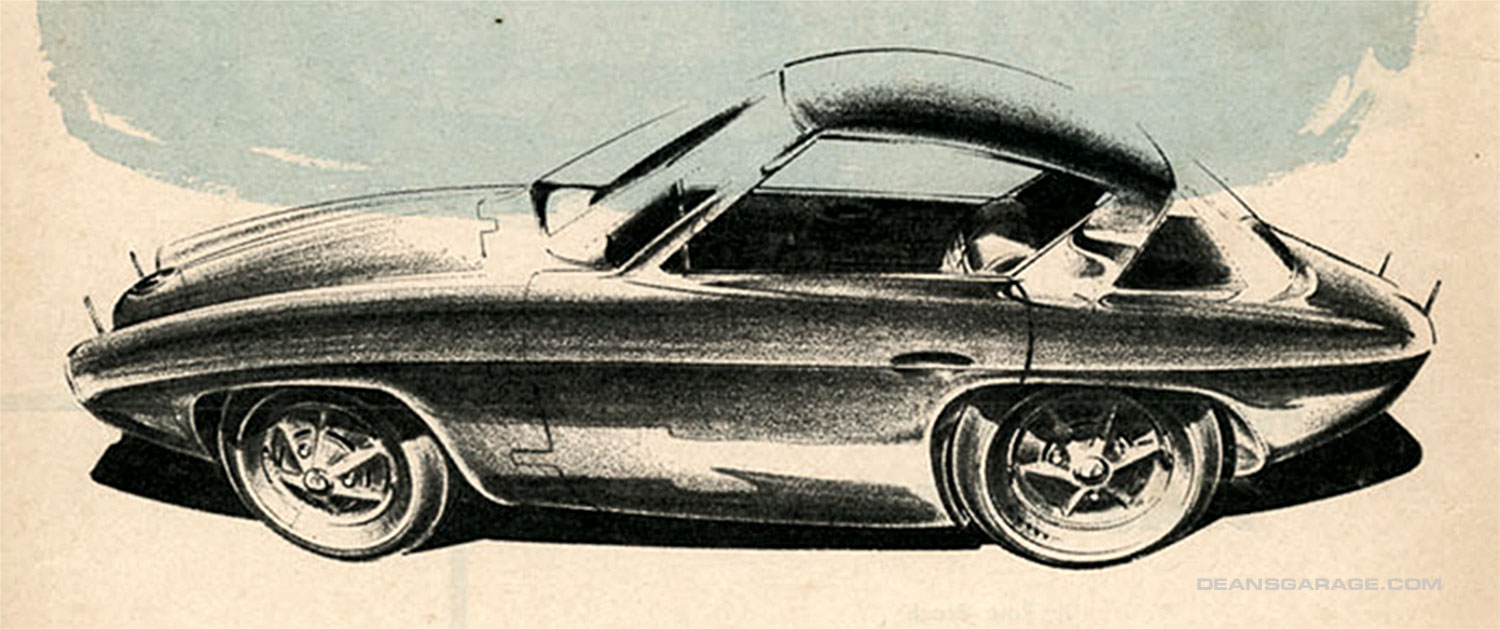

In the redesign, I stripped the car of all GM styling cliches, which I felt the design committee had added, and worked it into the type of vehicle that I’d like—one even suited to competition events. My enthusiasm paid off. Earle ordered more work on the car.

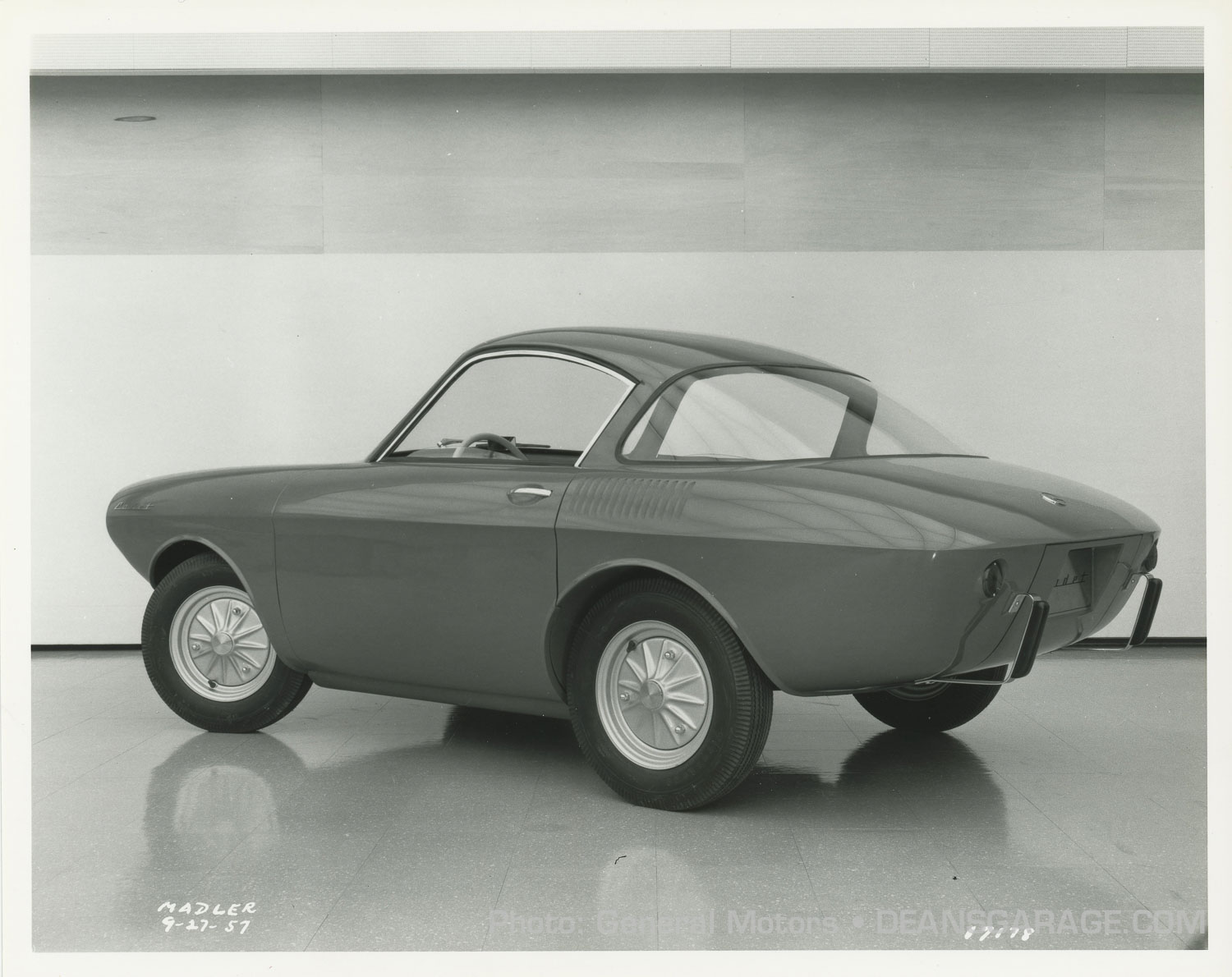

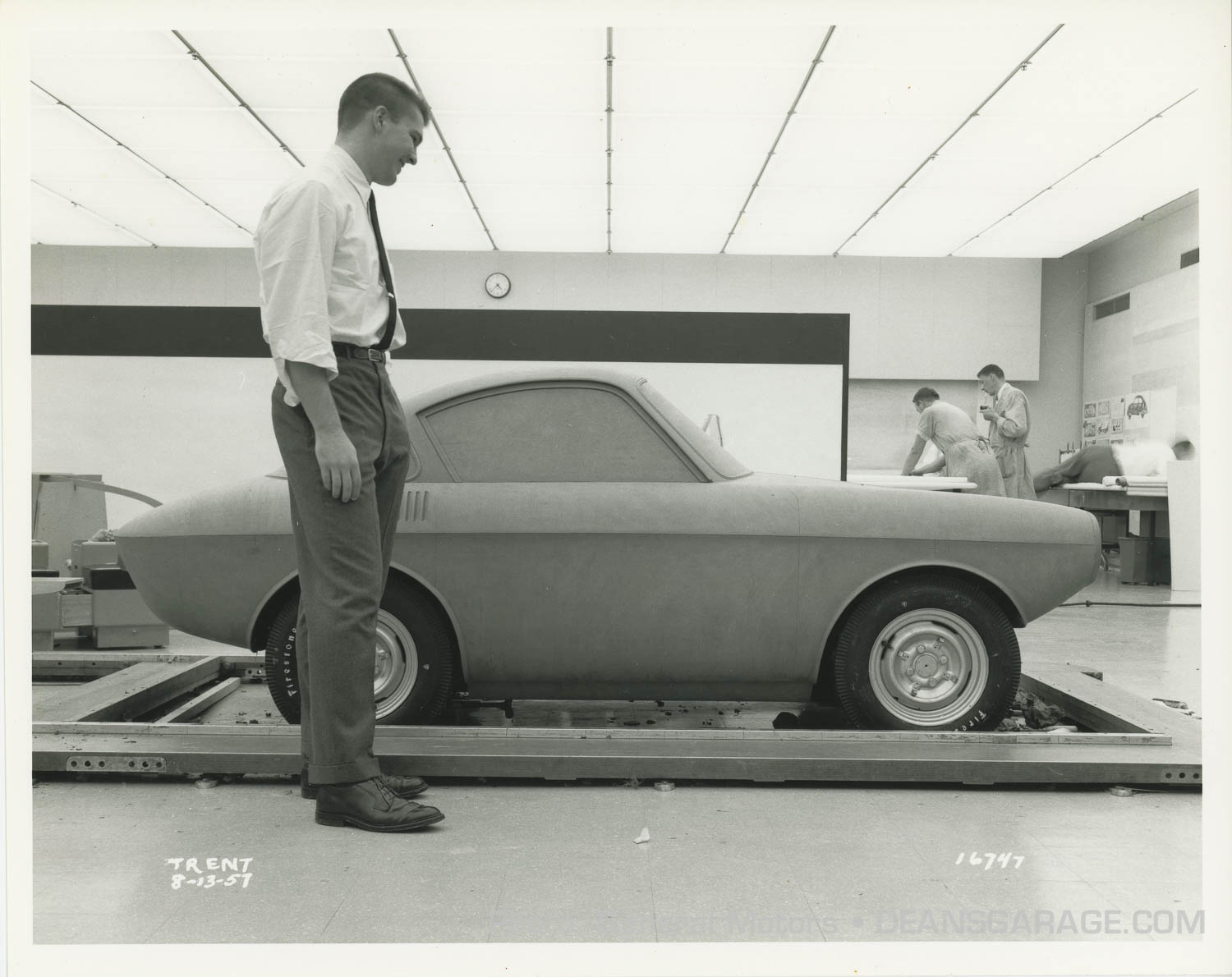

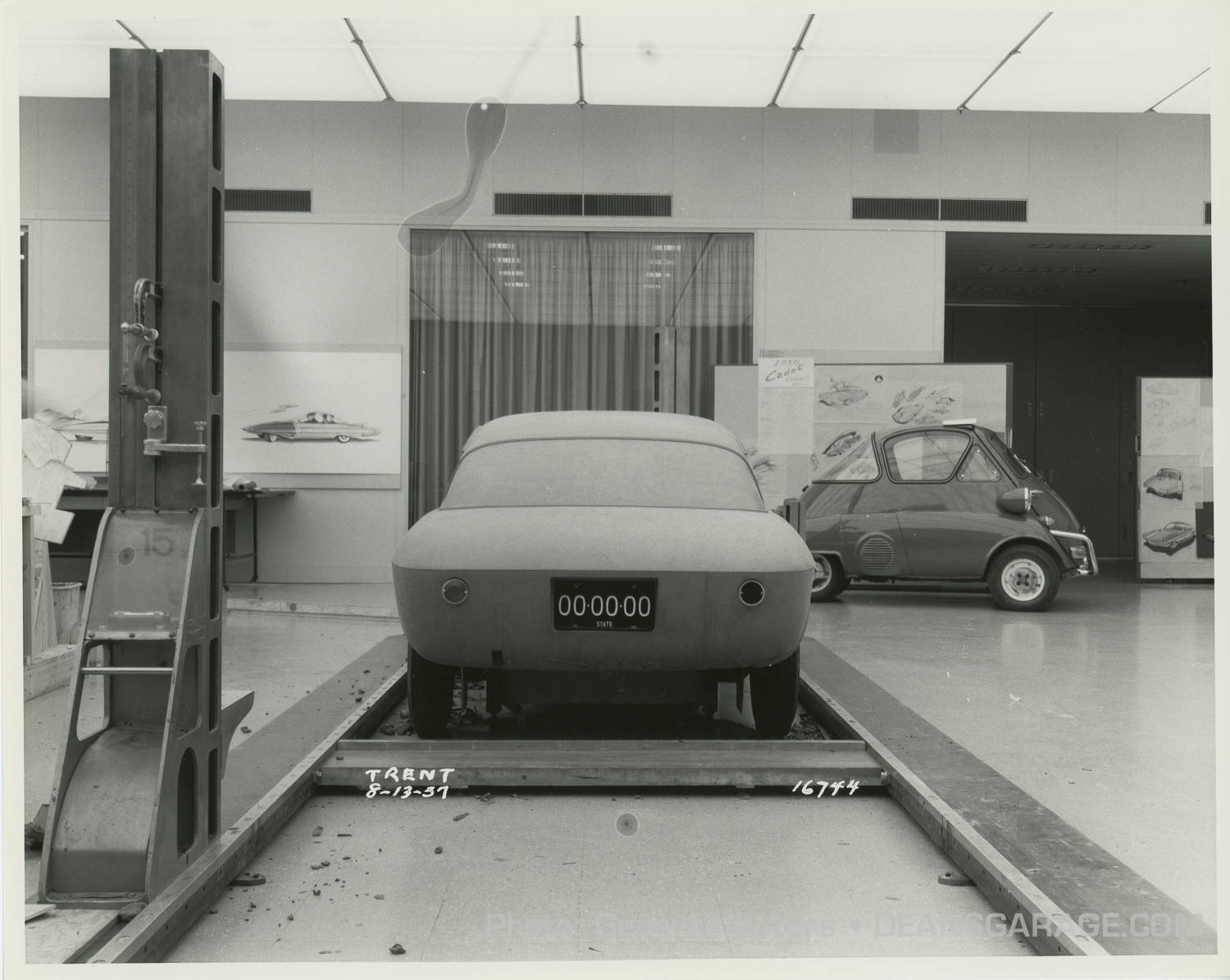

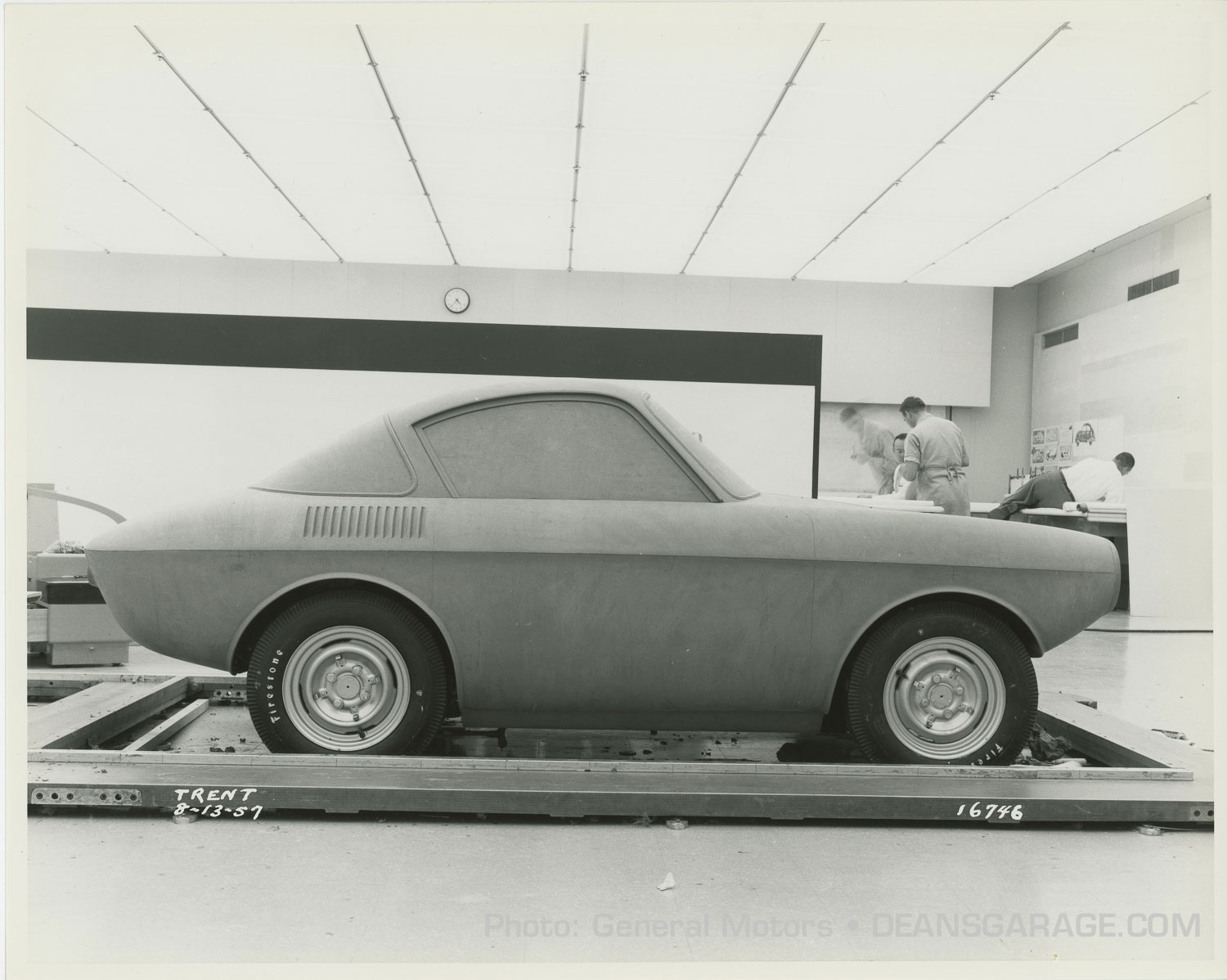

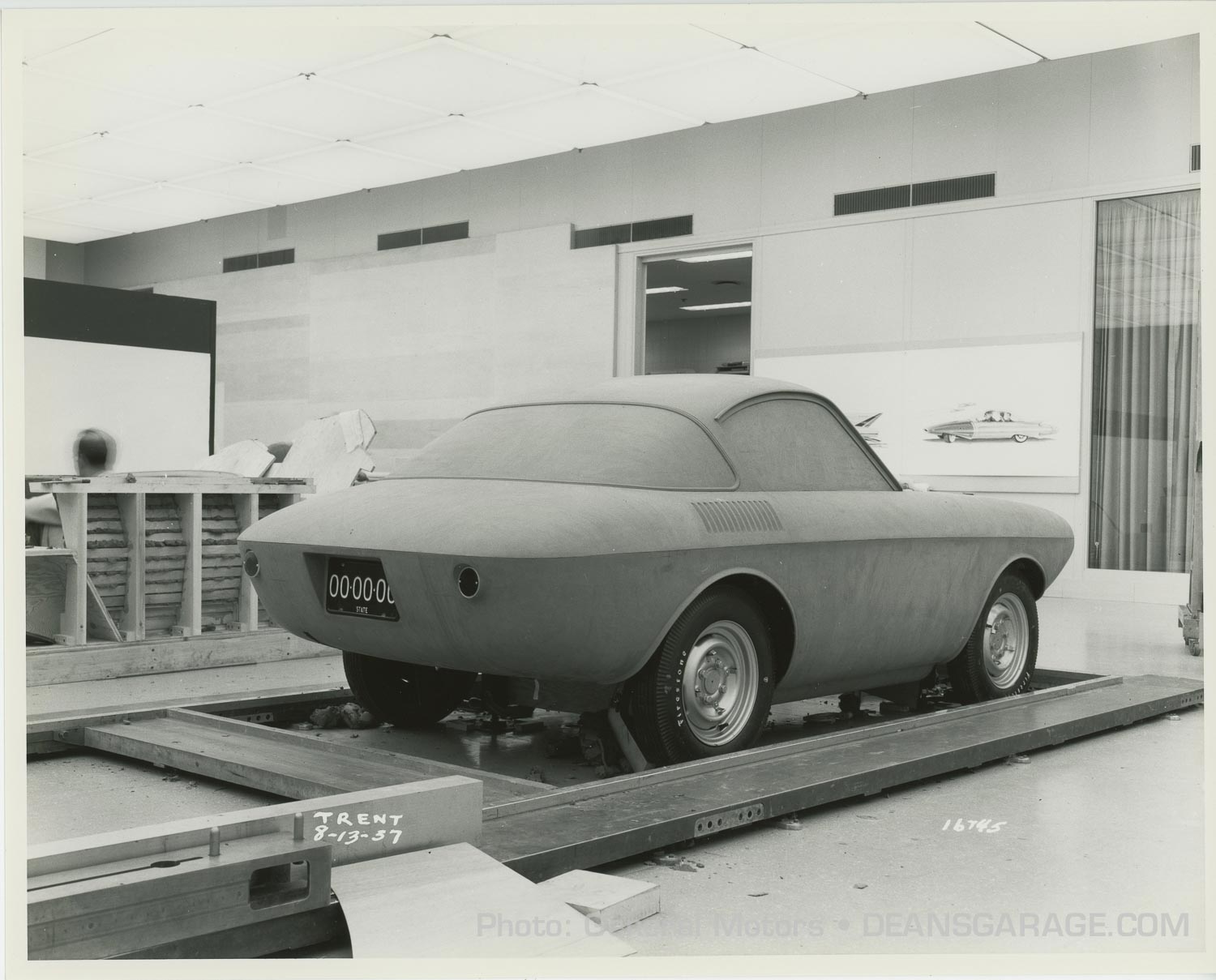

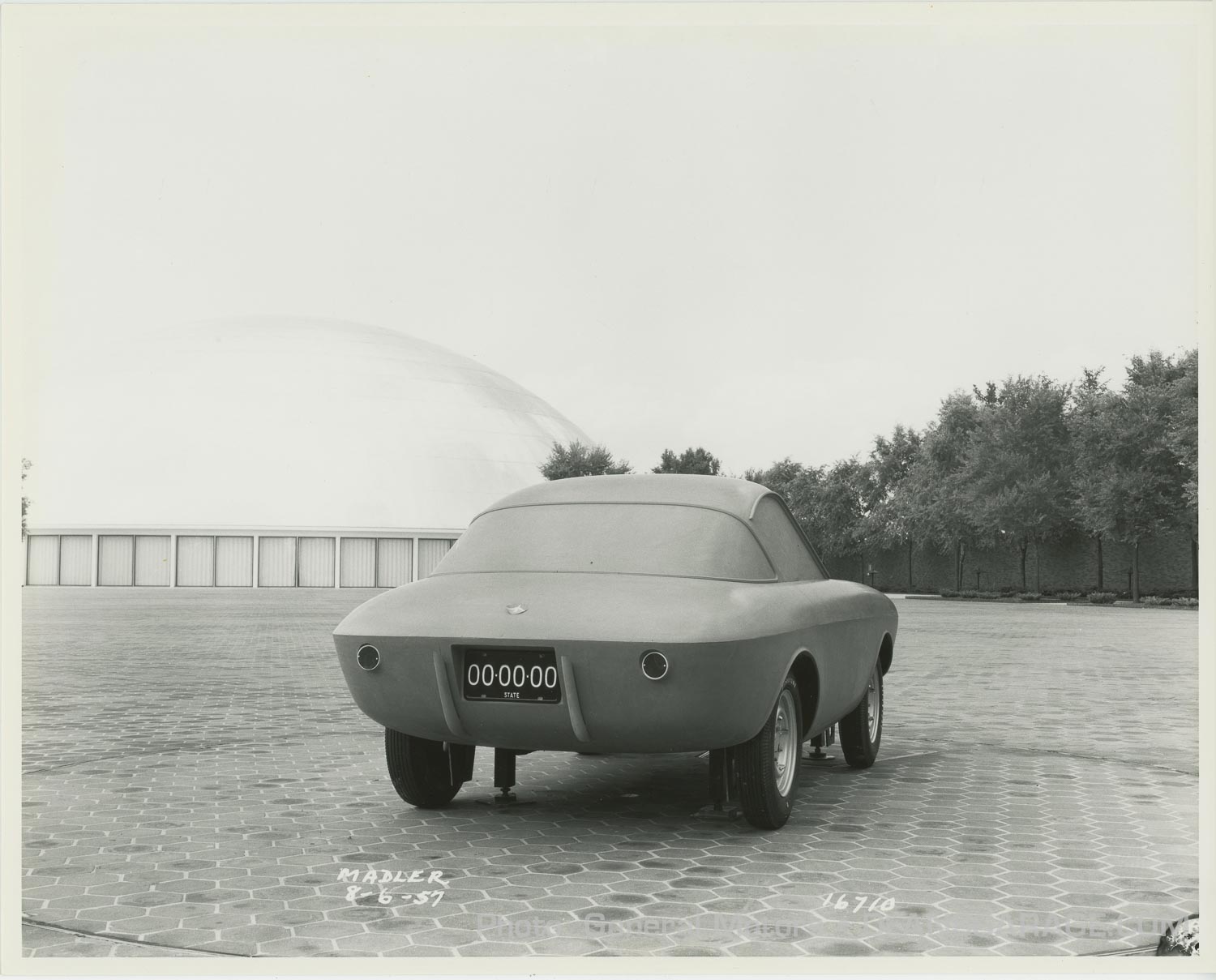

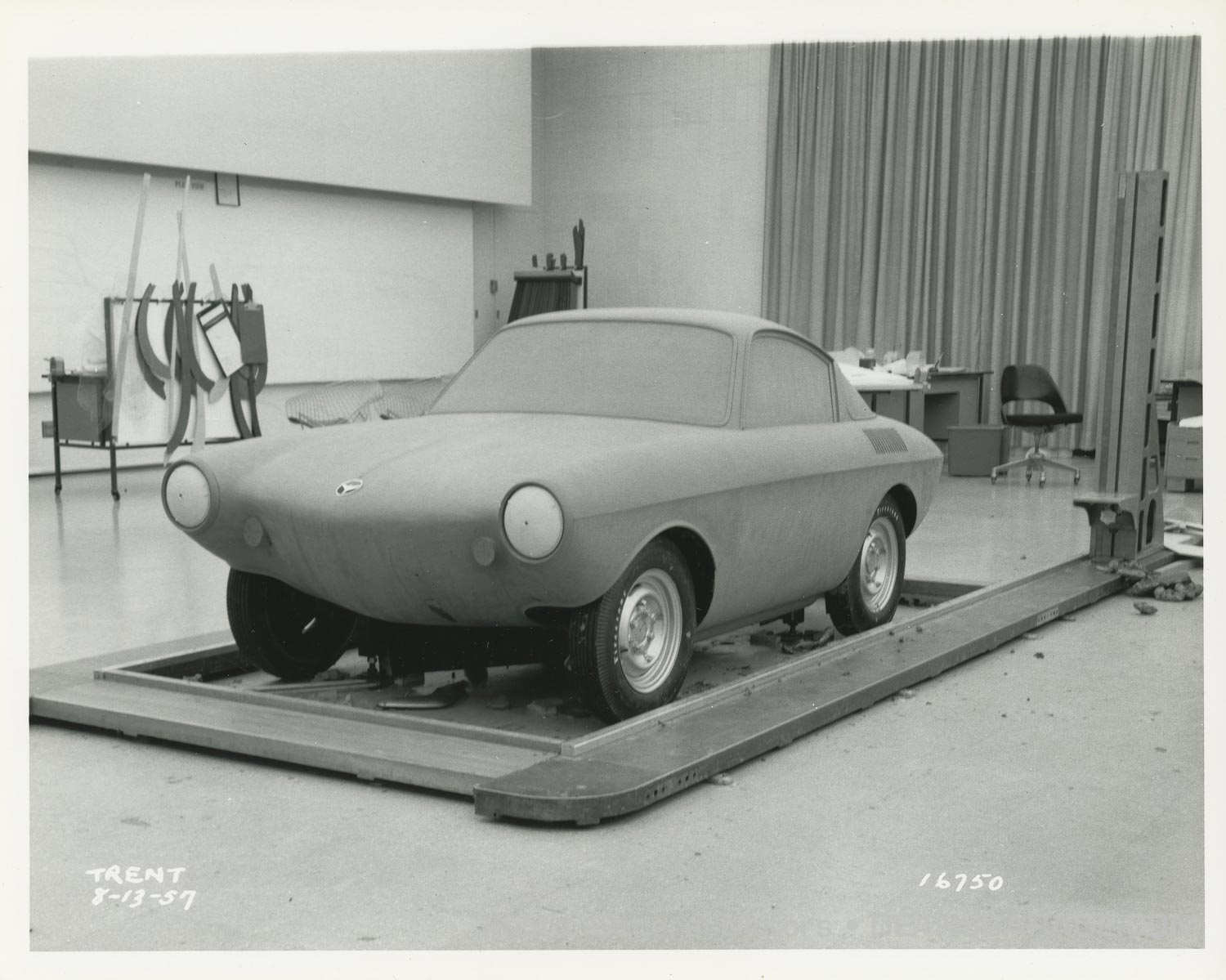

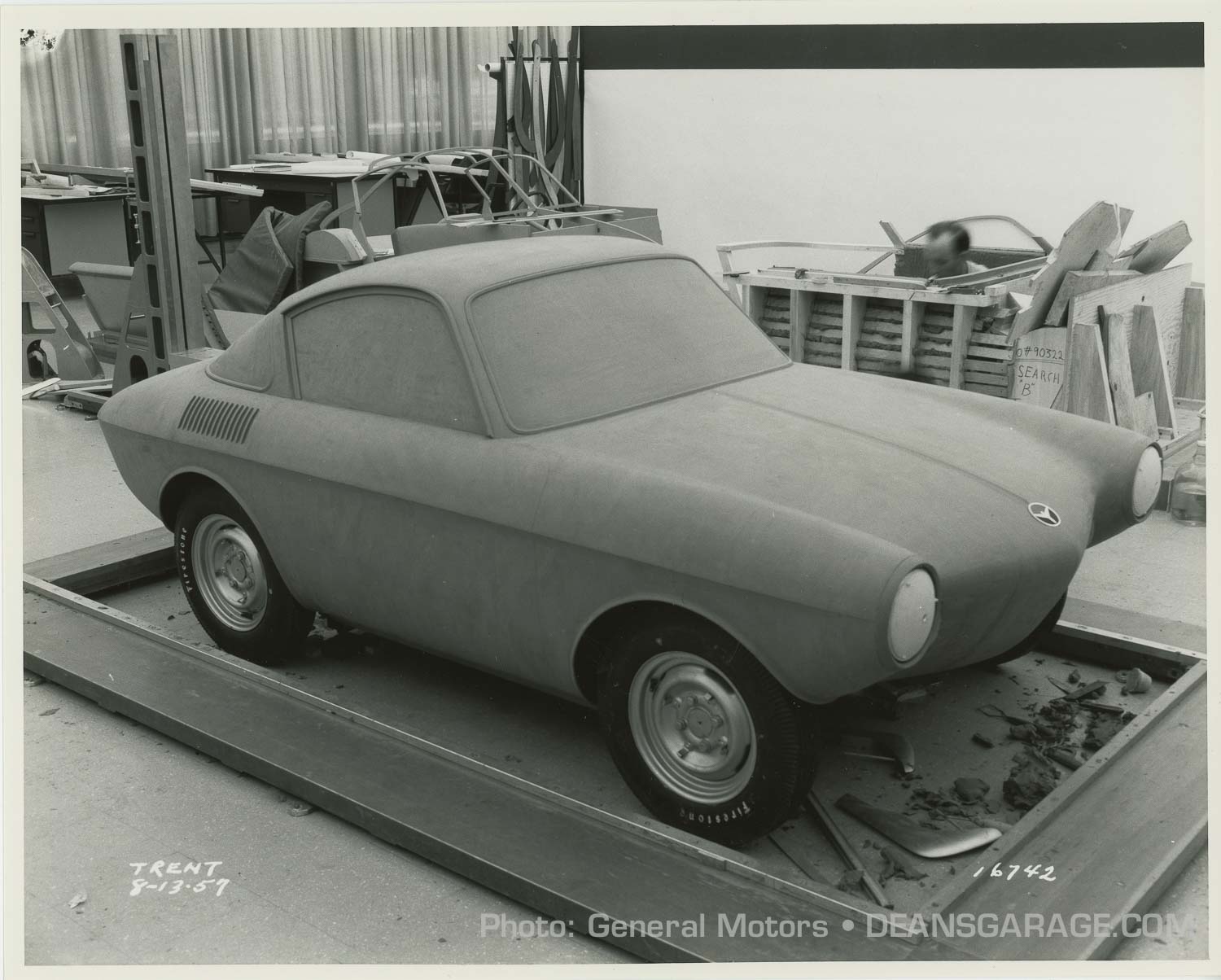

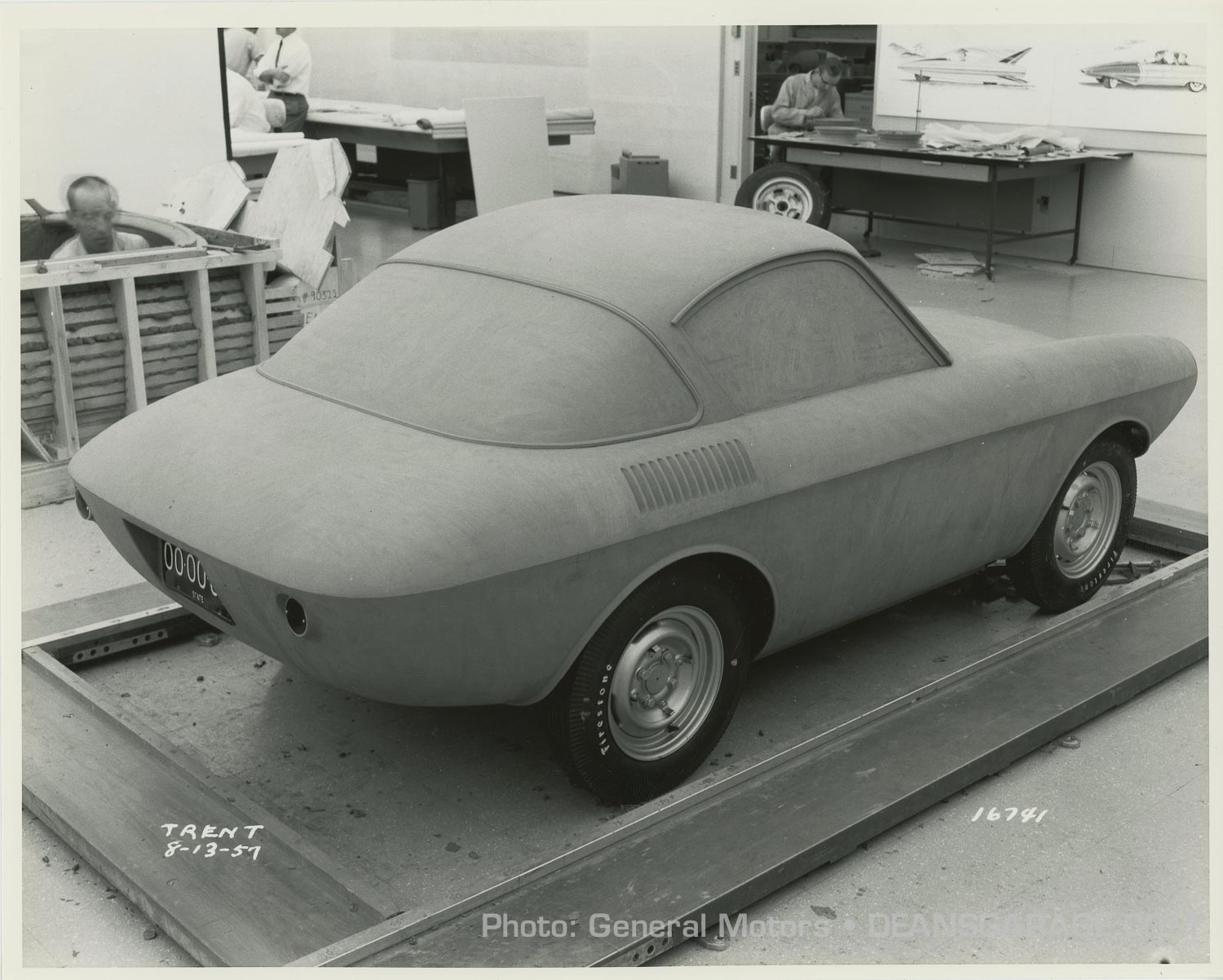

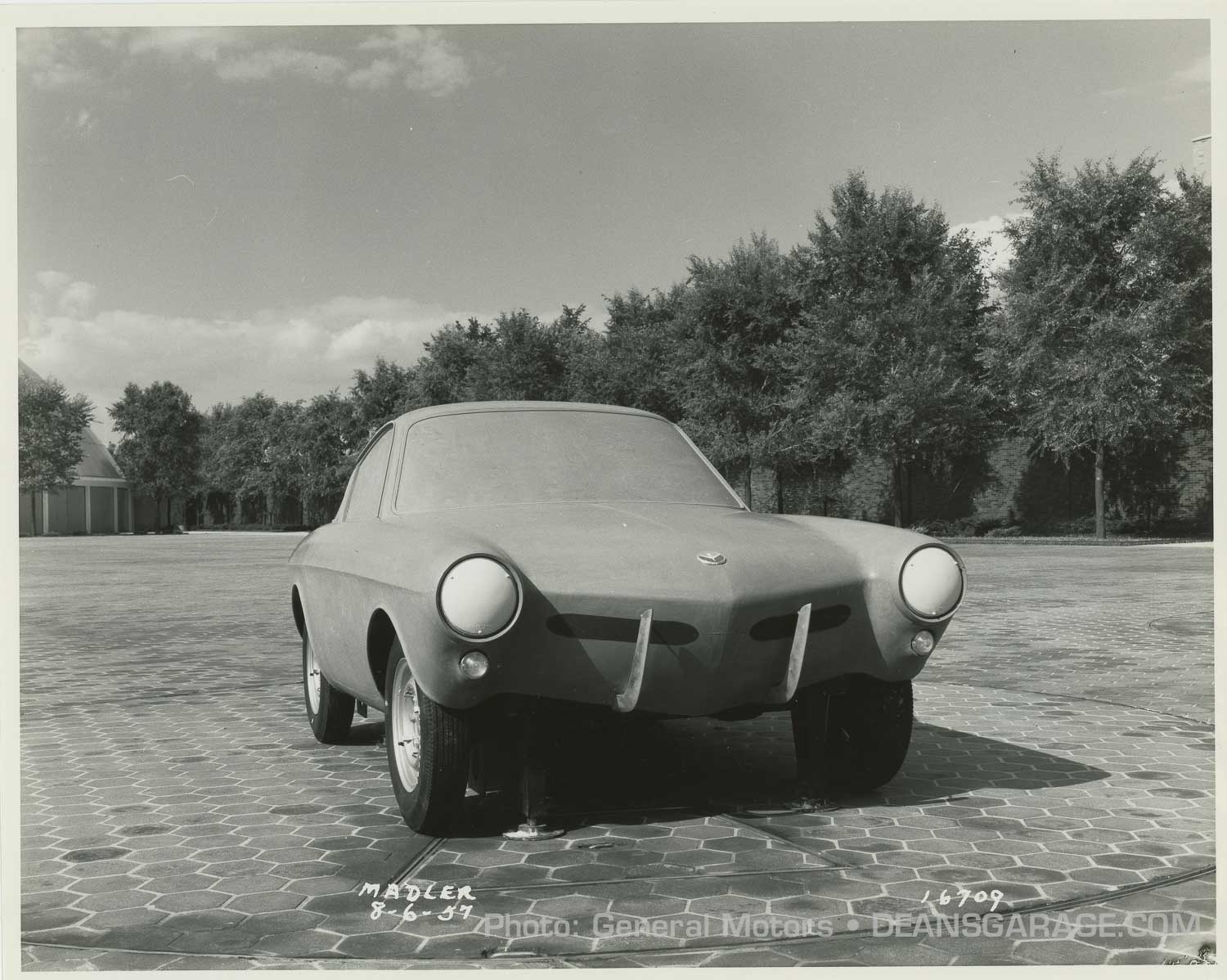

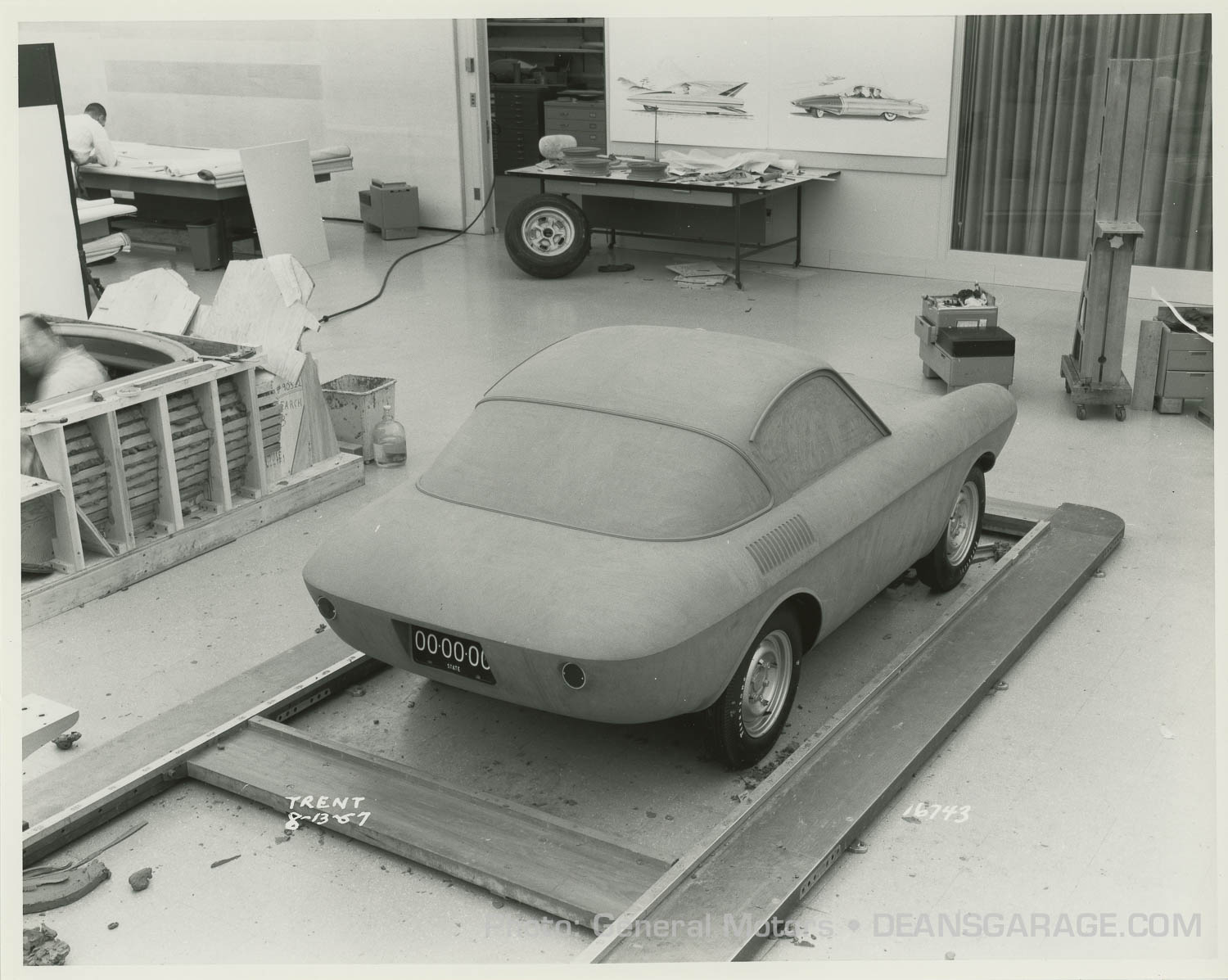

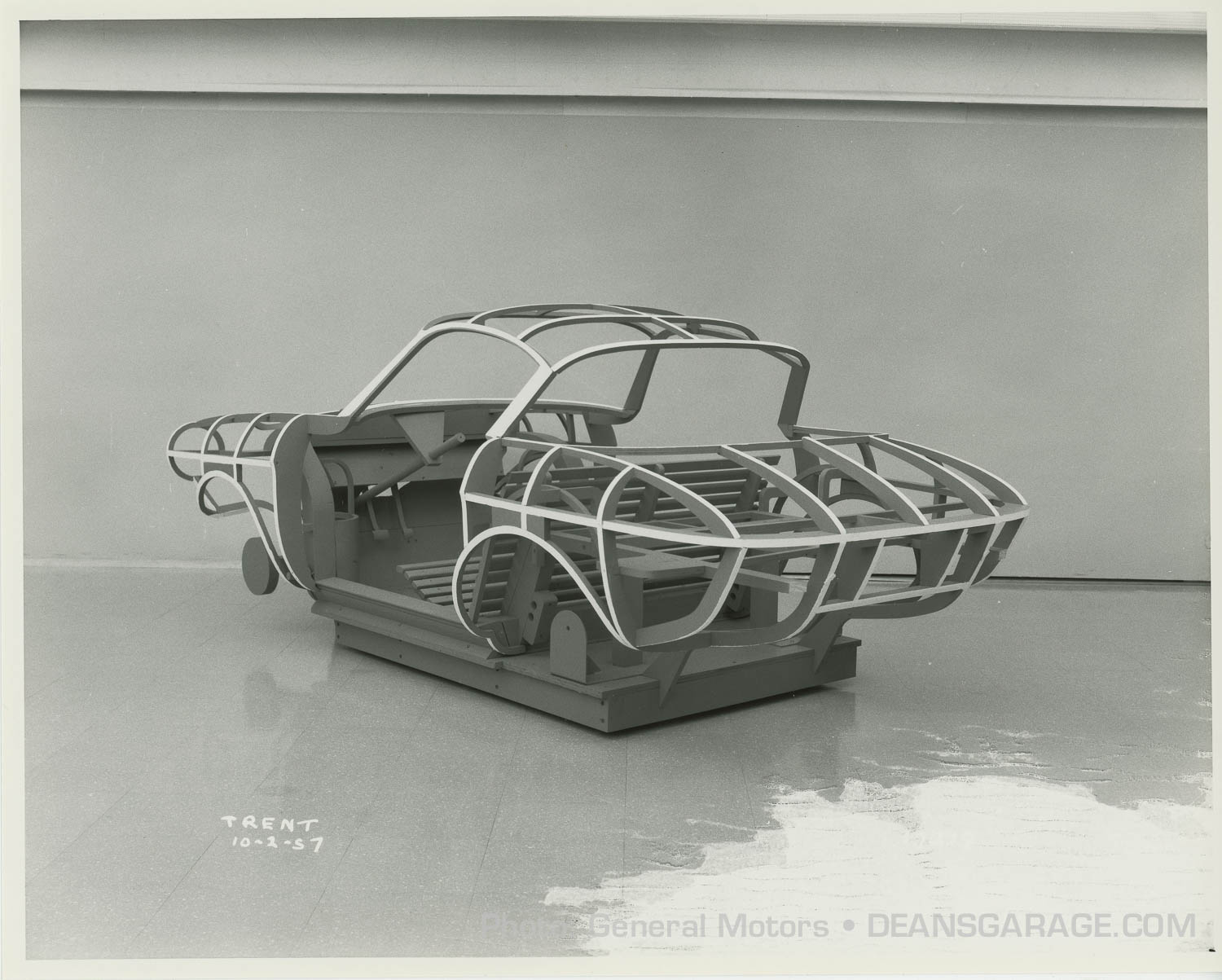

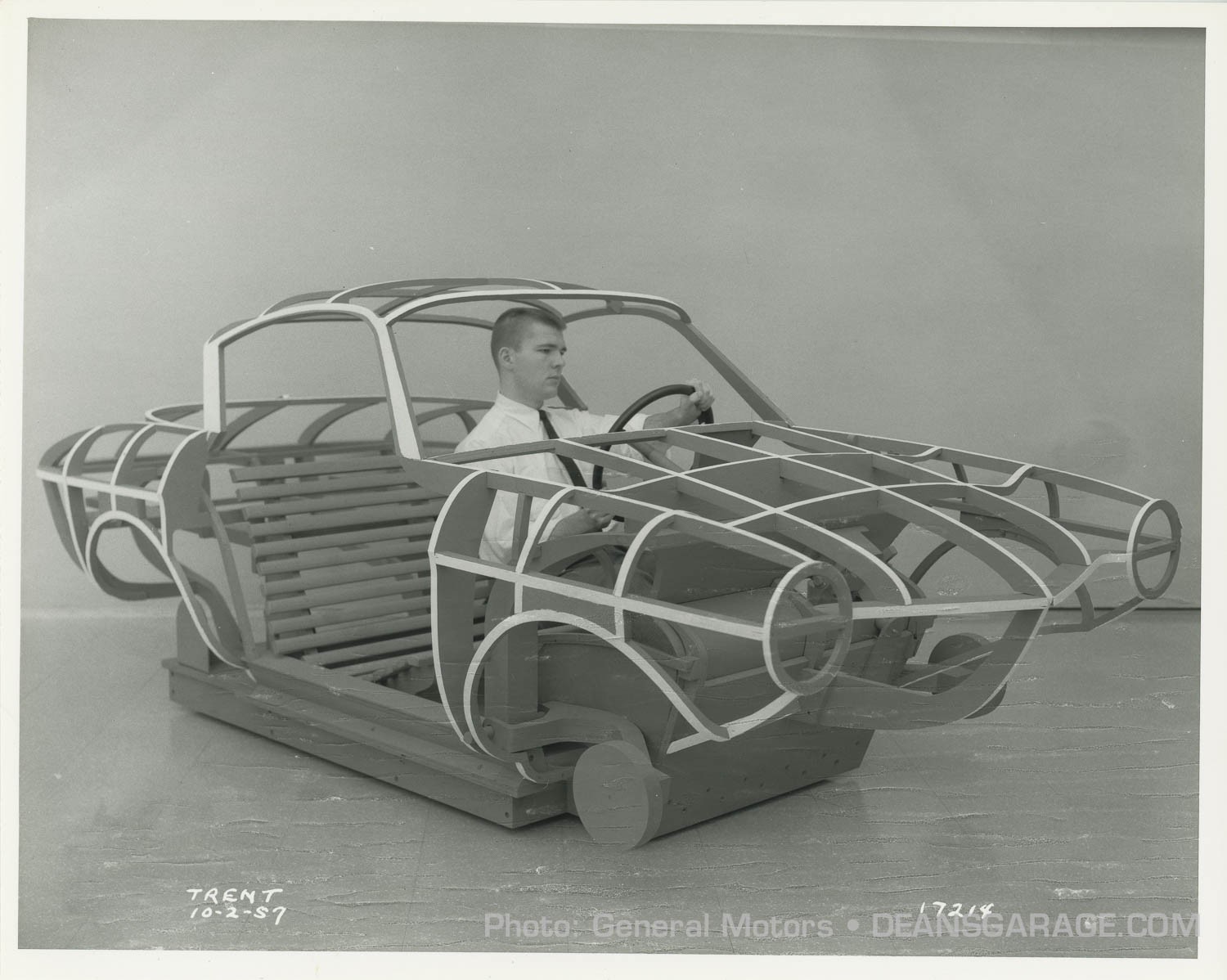

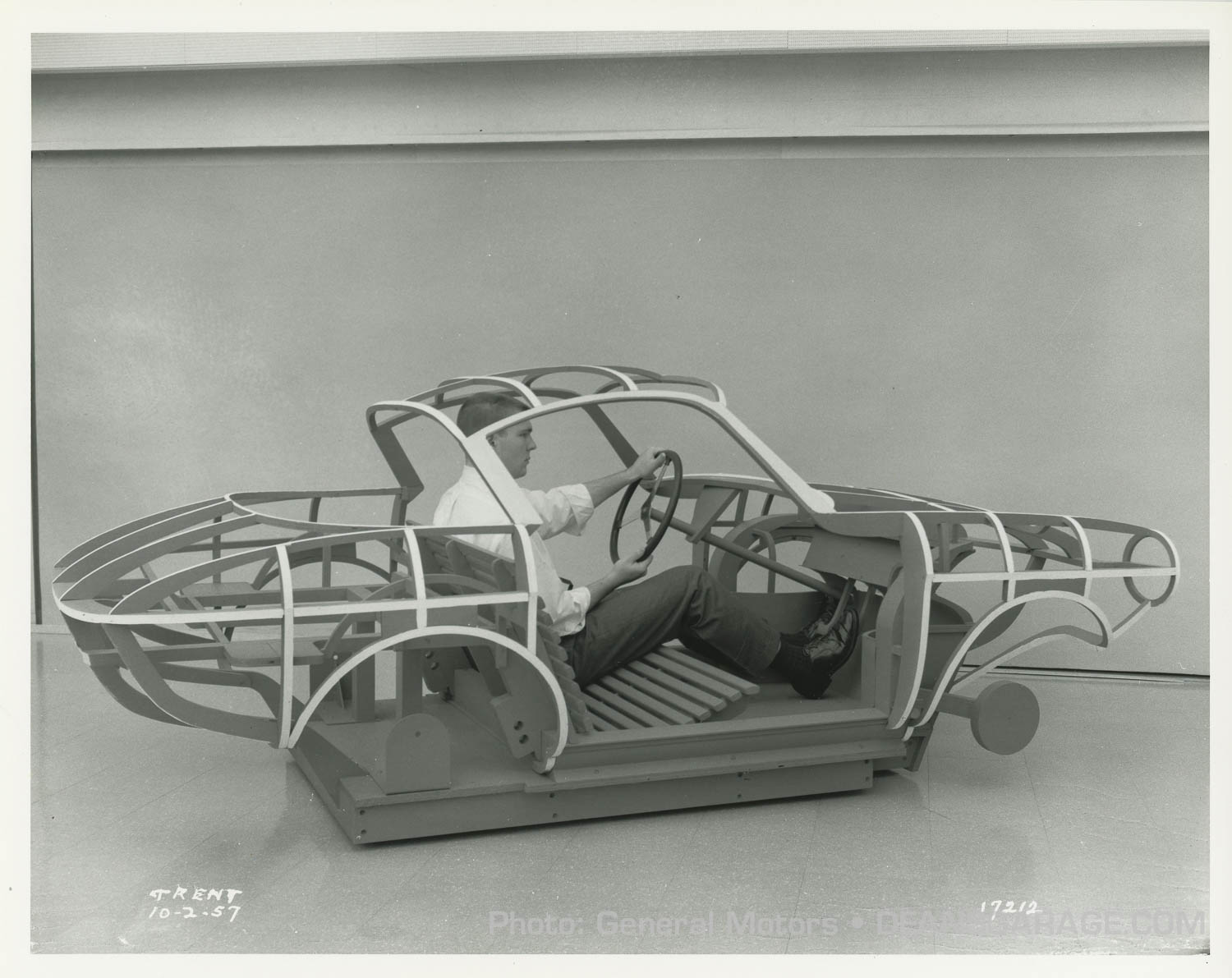

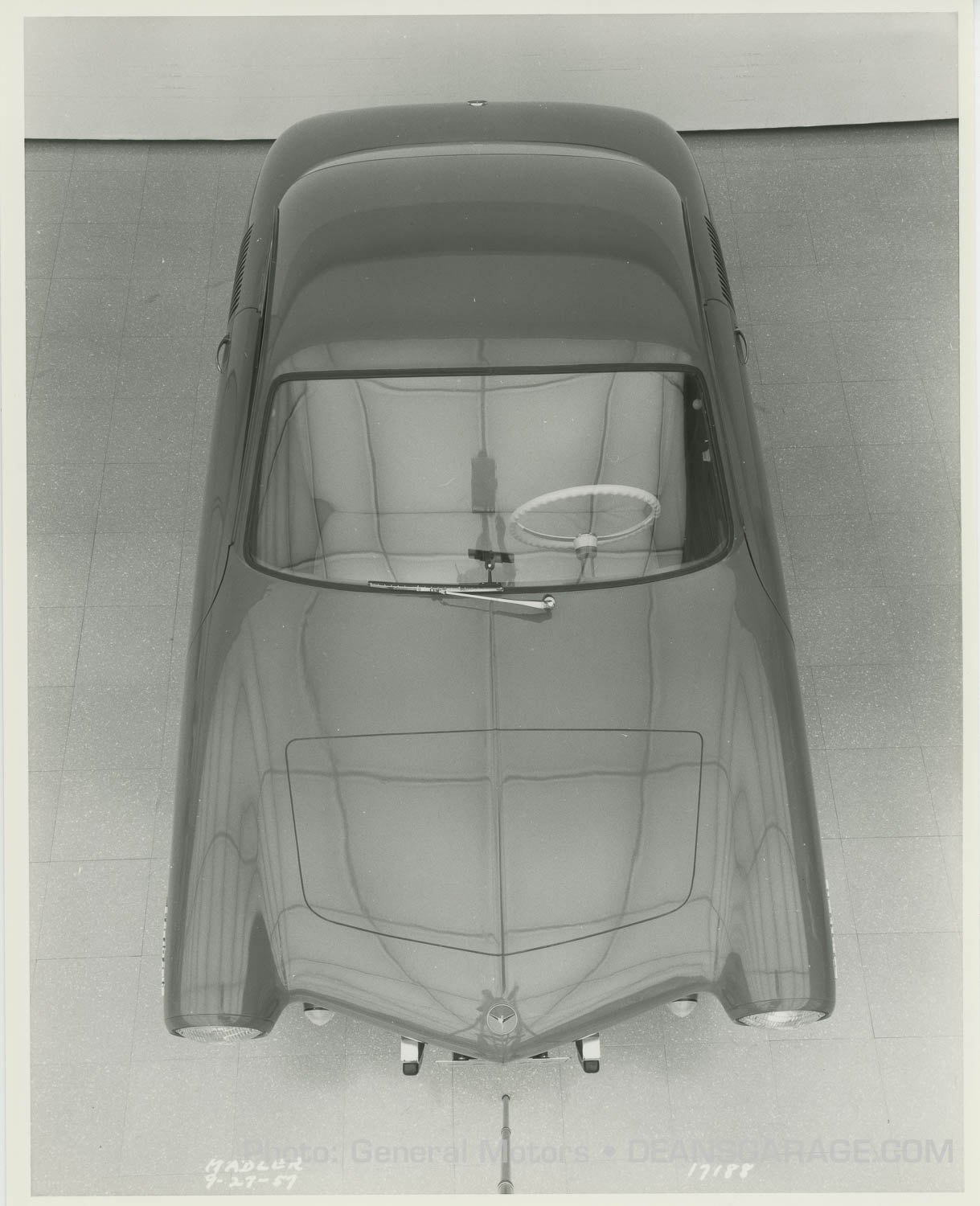

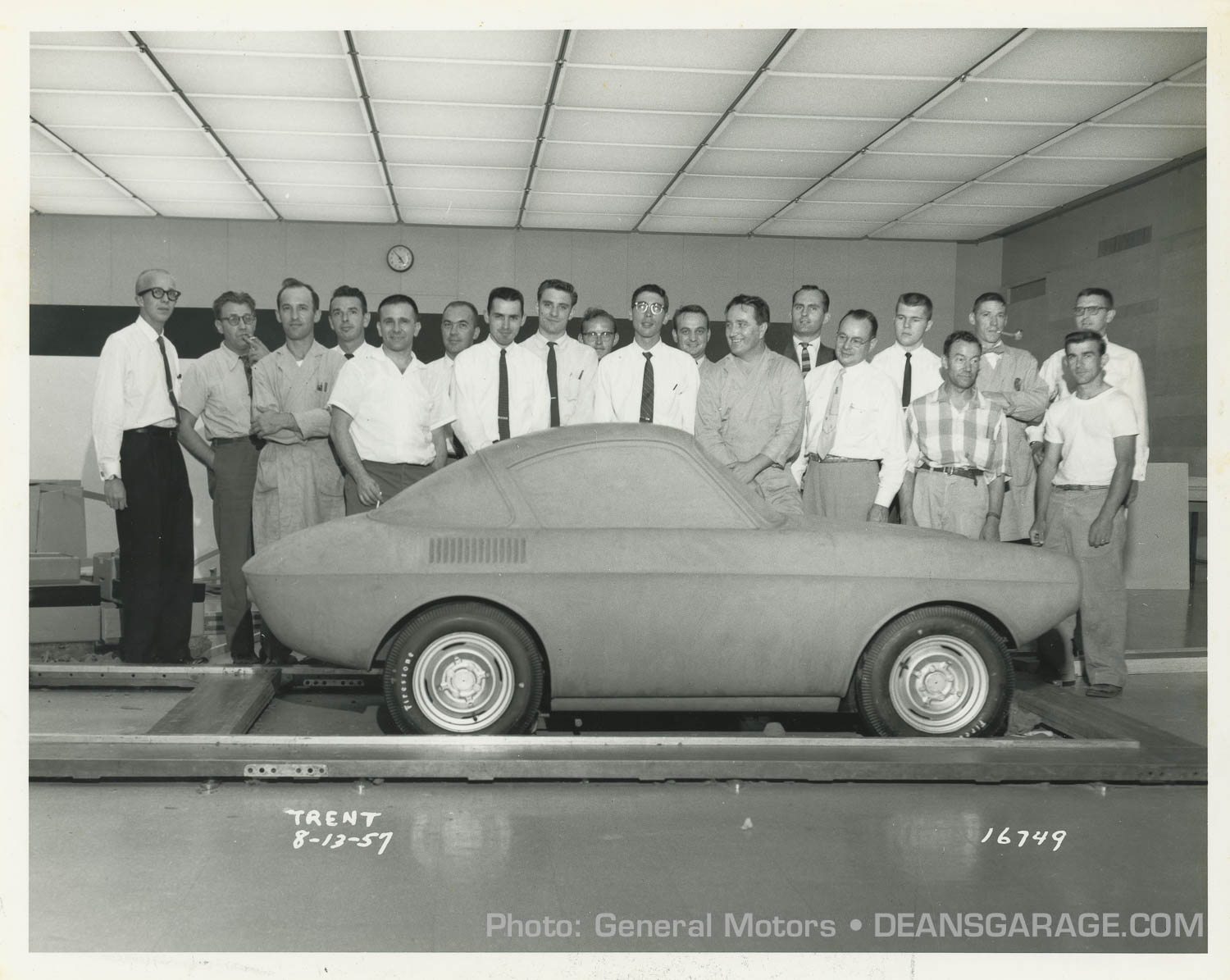

Caption: A full-size clay model was started in CADET combined sportscar lines with an extremely short wheelbase—63 inches! Born as a dream proposal, the car caused enthusiasm throughout GM. Its future: a mystery.

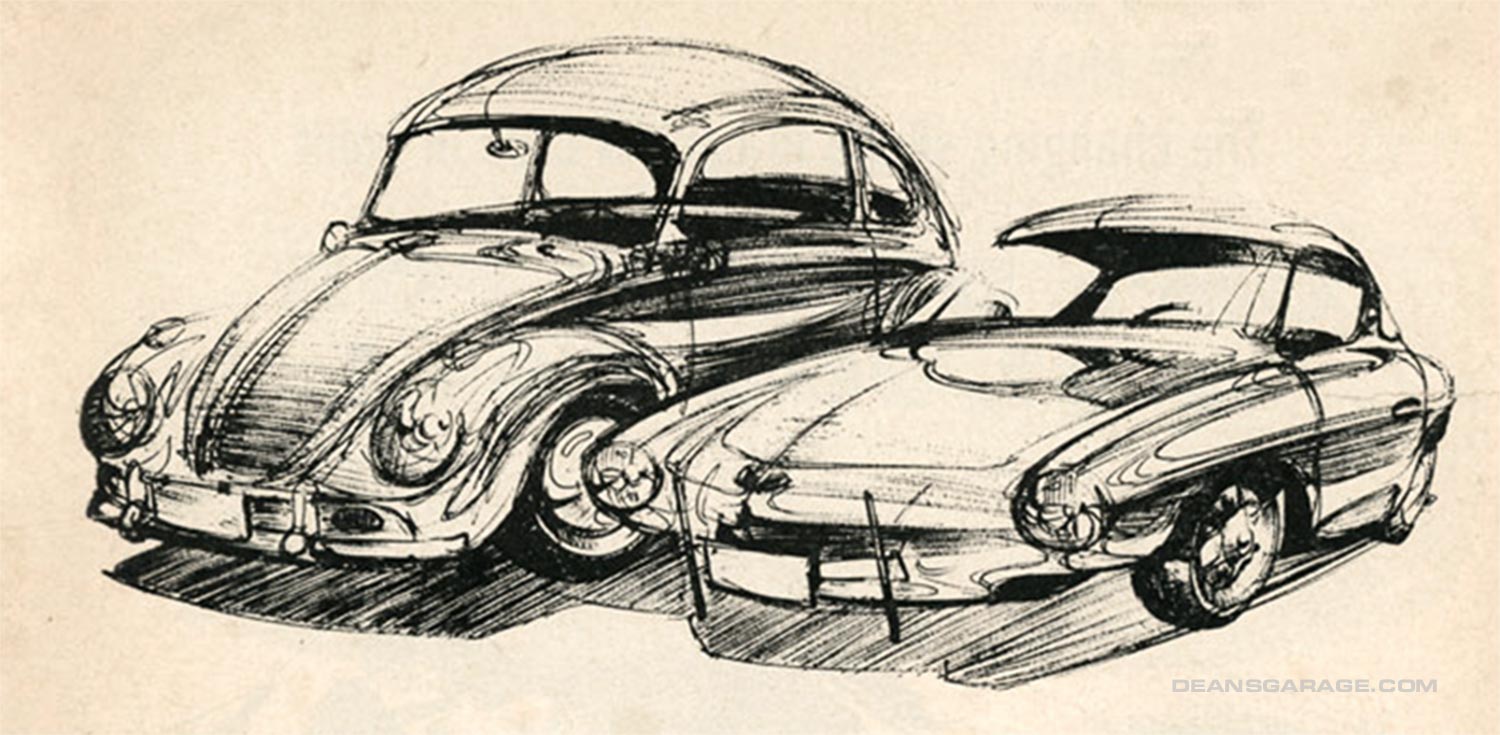

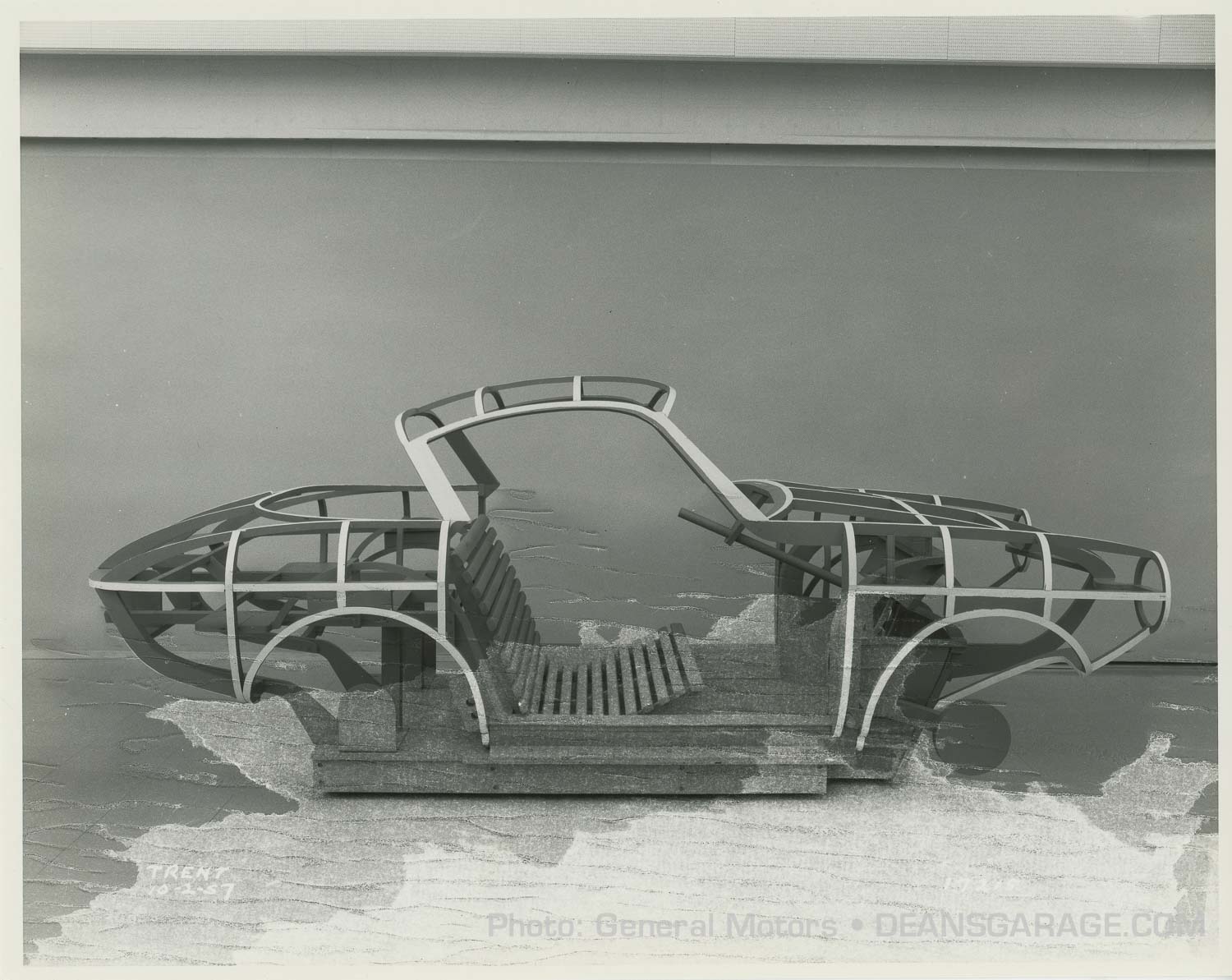

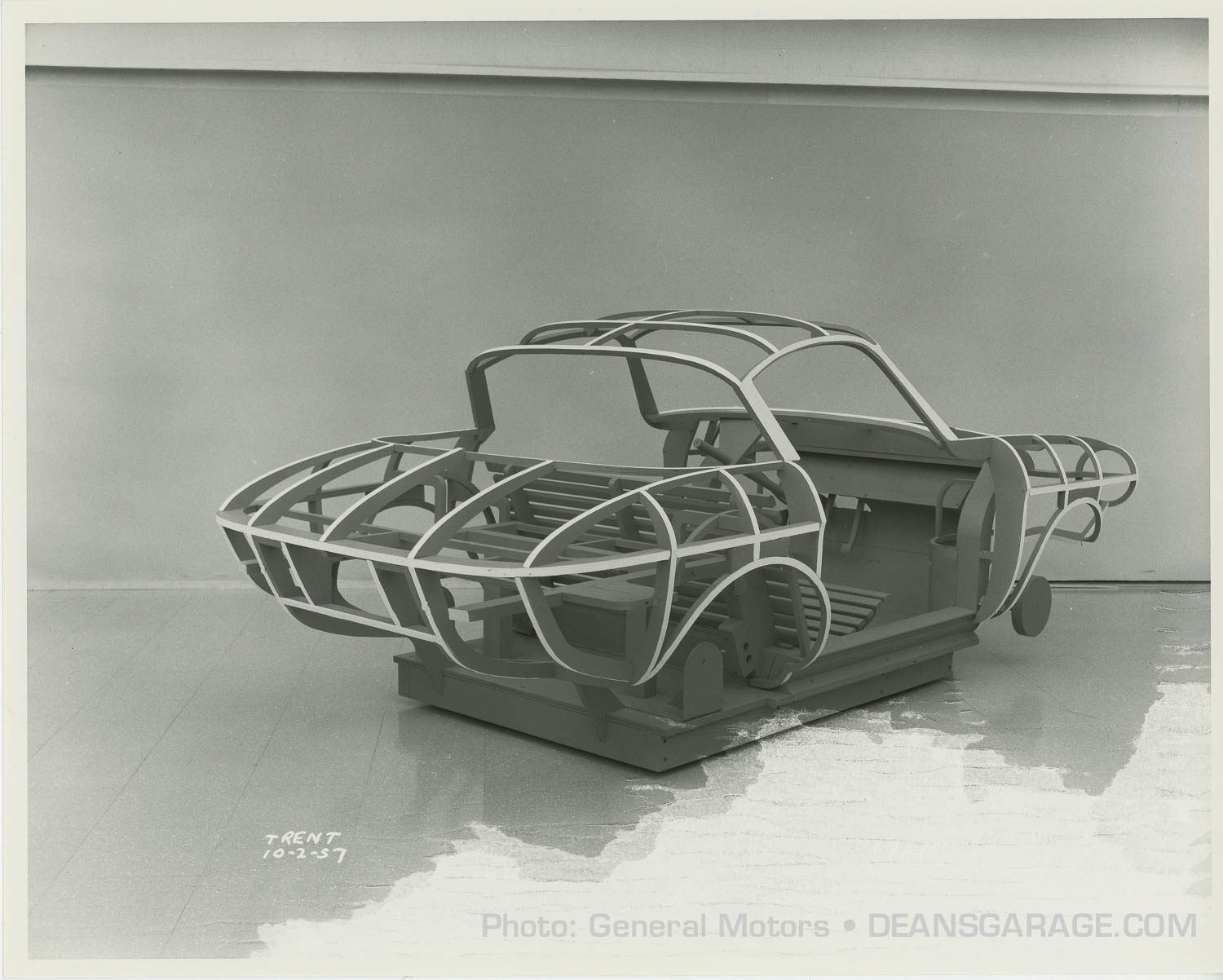

A full-size clay model was stated in conjunction with a full-size space buck so that entrance and seating ream could be evaluated. During this time, Earle also showed great interest in the lines of the beautiful little Karmann-Ghia. So it’s no wonder, then, that some of the roof line and front end of that car were reflected in the XP-79. The Ghia, incidentally, had a wheelbase of 94.5 inches; the Cadet was a mere 63 inches. It was small!

Another interesting point worth mentioning is that during the design stage of the Cadet, the car was engineered to be sufficiently intricate and complex so that if it ever were produced, GM could not he matched by any small company through imitation of a simple design. The quality and manufacturing cost were aimed at a level that could not be equaled, except perhaps by one of the other large auto makers.

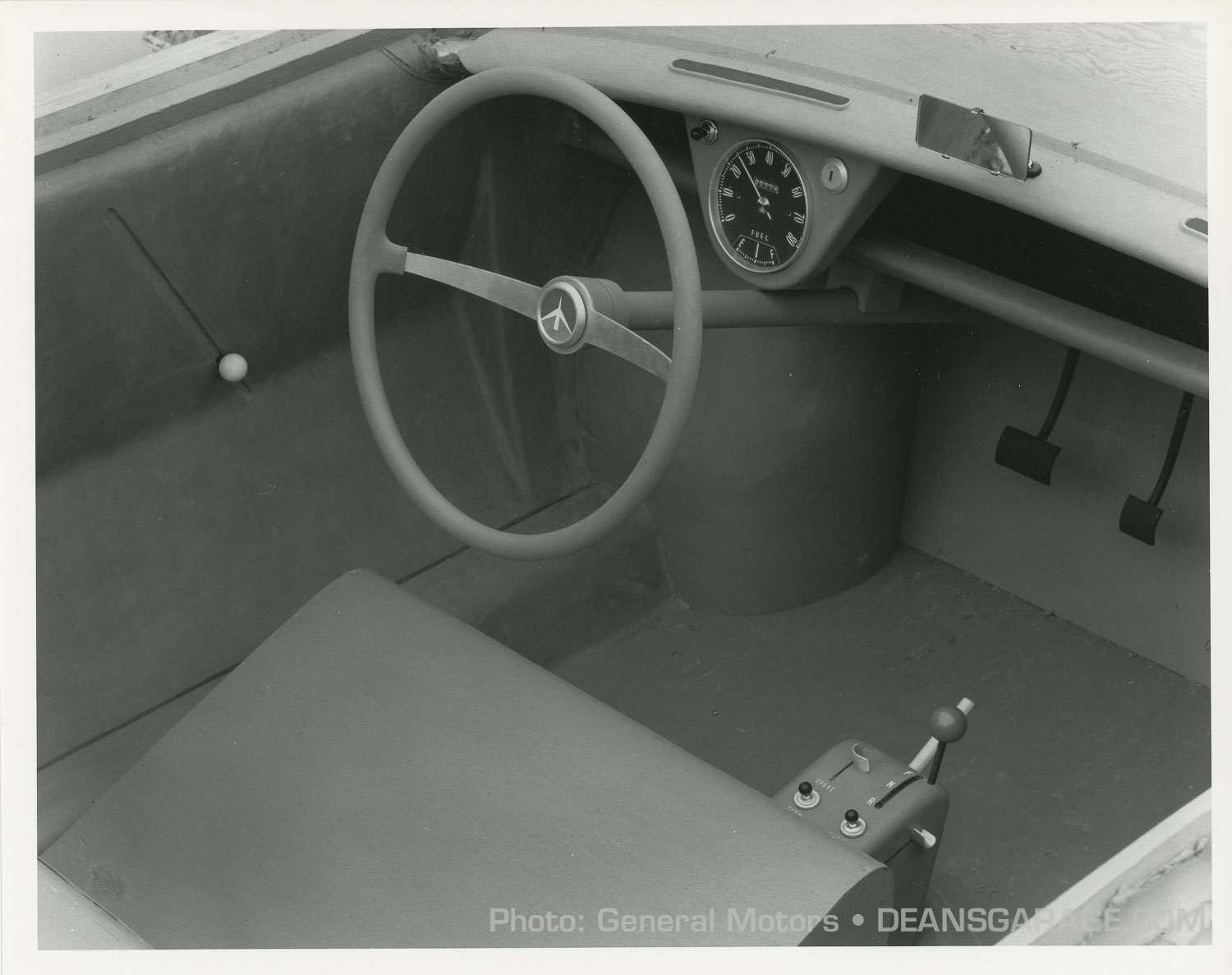

The full-size clay model and seating buck were coming on so easily and quickly that it was definitely decided to build up a complete full-scale mock-up of fiberglass for an executive showing. It went well. Nothing was “forced,” as is so often necessary in the give-and-take of design work where some features must be abandoned for economy. Wheels were stamped in a strong and pleasing six-point star pattern that eliminated the need for a wheel cover. The whole shape would have been marred by heavy conventional bumpers, so push-bars of dual tubing were used. The interior was neat. The inside width, an important item in a small car, was increased slightly by eliminating window cranks and substituting a simple slide device that lacked in position when twisted.

The target price of the Cadet was $1,000. Only that for a car that had more interior room than the Karmann-Ghia, would out-run the Volkswagen, park as easily as an Isetta, and operate cheaper than a Renault. Powerplant and running gear for the Cadet were envisioned as a unit similar to the German Lloyd—two cylinders, air-cooled, with overhead valves, hemispherical combustion chambers and an ignition driven directly off the cam. Transmission would be an infinitely variable hydraulic unit with a final lockup of 1-to-1, Rear axles, because of the rear engine transaxle unit, were of the swing type, suspended by laminated torsion bars as in the VW. Front suspension was of the “leading arm” type with coil springs.

Two weeks before the show, Earle decided on a companion vehicle, using the same front end as far back as the windshield posts. The wheelbase, however, was to be extended a few inches and a small van body for commercial applications was mounted. It was completed a few hours before the show, and both it and the Cadet coupe were then painted a beautiful metallic blue.

Top management turned thumbs down. One very high executive even refused to walk across the room to look at the cars. There was no place for them in the GM line. Curtains were quietly drawn, and the cars rolled away to what appeared to be obscurity.

Stan Mott’s take on a small Chevrolet from a previous post on Dean’s Garage: LINK.

If I recall correctly “Cadet” was the working name of the compact model that GM designed and texted just after WW2 but — again — didn’t pursue.

There was also an effulgence of smaller cars in a special show when Frank Winchell was running Chevrolet R&D. I have my photos somewhere.

It’s amazing how small it really is

America was not ready.

With that little two cylinder hemi engine, the Cadet would have blown the door off of an Isetta!

Nice!

I see the Corvette Stingray roofline in the coupe.

Anybody else see the Vega panel truck in the lines of the panel?

Bruce Brooks

In the group photo, second from the left in the back row is Joseph Henelt and in the back row forth from the right is Chuck Jordan. Does anyone from GM Design’s past recognize anyone else?

Some things are a given: GM should never have entered the small car/compact markets.

In the studio group photo also identified are Carl Renner first on the left in the back row and Joe Biondo second from the left in the front row, also Al Andreas second from the right and John Bird fifth from the right in the back row. Thanks to Frank Fischer for the info ID’s.

Re: John B: Yes, I immediately went to the comments to CTRL-F for “vega” and your comment popped up.

i also notice the strong vega side profile resemblance right away.

Does anyone know what happened to these cars? Do they still exist?