George Walker and the 1964 Lincoln Continental Mark IX

By Jim and Cheryl Farrell

When George Walker became a consultant to Ford in late 1940s he extracted conditions from Henry Ford II which included Walker’s control of all publicity about Ford design. Walker was also able to keep his lucrative private design business and his interest in another business (Trim Trends) that sold automotive trim parts to multiple manufacturers.

The last condition given Walker was the right to insert two of his employees, Elwood Engel and Joe Oros, into the Ford Design Department. Oros and Engel, although not employees of Ford, were there full-time, and had the right to design and create clay models of their own Ford, Lincoln or Mercury proposals if they didn’t like the designs proposed by Ford designers. That arrangement didn’t work very well and caused even more dissension among Ford designers.

On May 22, 1955, HFII’s solution was to make Walker a Ford vice president and general manager of the Design Department, which Walker promptly renamed the Ford Styling Center. Engel then became Walker’s assistant manager, and in 1956, he named Oros as head of the Ford design studio.

Ford policy mandated that all executives retire at age 65. As Walker approached his 65th birthday in 1961, he was obsessed that Oros or Engel (preferably Engel) succeed him. Gene Bordinat, as head of the Lincoln-Mercury design studio, was Engel’s primary competition to succeed Walker. That meant that Walker was actively trying to undermine Bordinat and build up Engel.

Ben Mills, then head of Lincoln-Mercury Division, didn’t trust Walker. He felt Walker and Engel had pushed through the design of the disastrous 1958 Lincoln without much consideration of its salability. Mills also wanted a smaller Lincoln that displayed obvious continuity with past Lincolns. That directive was made clear to Bordinat who was supposed to be designing the ’61 Lincoln in his studio. Mills also wanted a longer nine-year design cycle for Lincoln.

Walker and Engel both were aware of Mill’s displeasure. Although Engel’s design for the ’61 Lincoln started out as a Thunderbird proposal, it later became a Lincoln proposal. Walker saw it as a feather in Engel’s cap even though his ’61 Lincoln design had no continuity with past Lincolns. Engel’s ’61 Lincoln proposal beat out the one from Bordinat’s studio that had an unfortunate similarity to the 1958-60 Lincoln—which by that time, nearly everyone at Ford disliked. Bordinat followed the rules; Engel didn’t—and Engel’s car won.

All of the above is prologue to what happened after Engel’s winning ’61 Lincoln proposal was moved upstairs into Bordinat’s Lincoln-Mercury studio to be productionized. Although Walker and Engel had lucked out with the winning ’61 Lincoln design, Walker quickly figured out that if Engel was also able to design the next Lincoln Continental, which under the old rules was due for change in 1964, it would go a long way towards Engel‘s appointment as his successor. Walker encouraged Engel to hand pick the best designers available, and to quickly began work on a car they called the 1964 Lincoln Continental Mark IX.

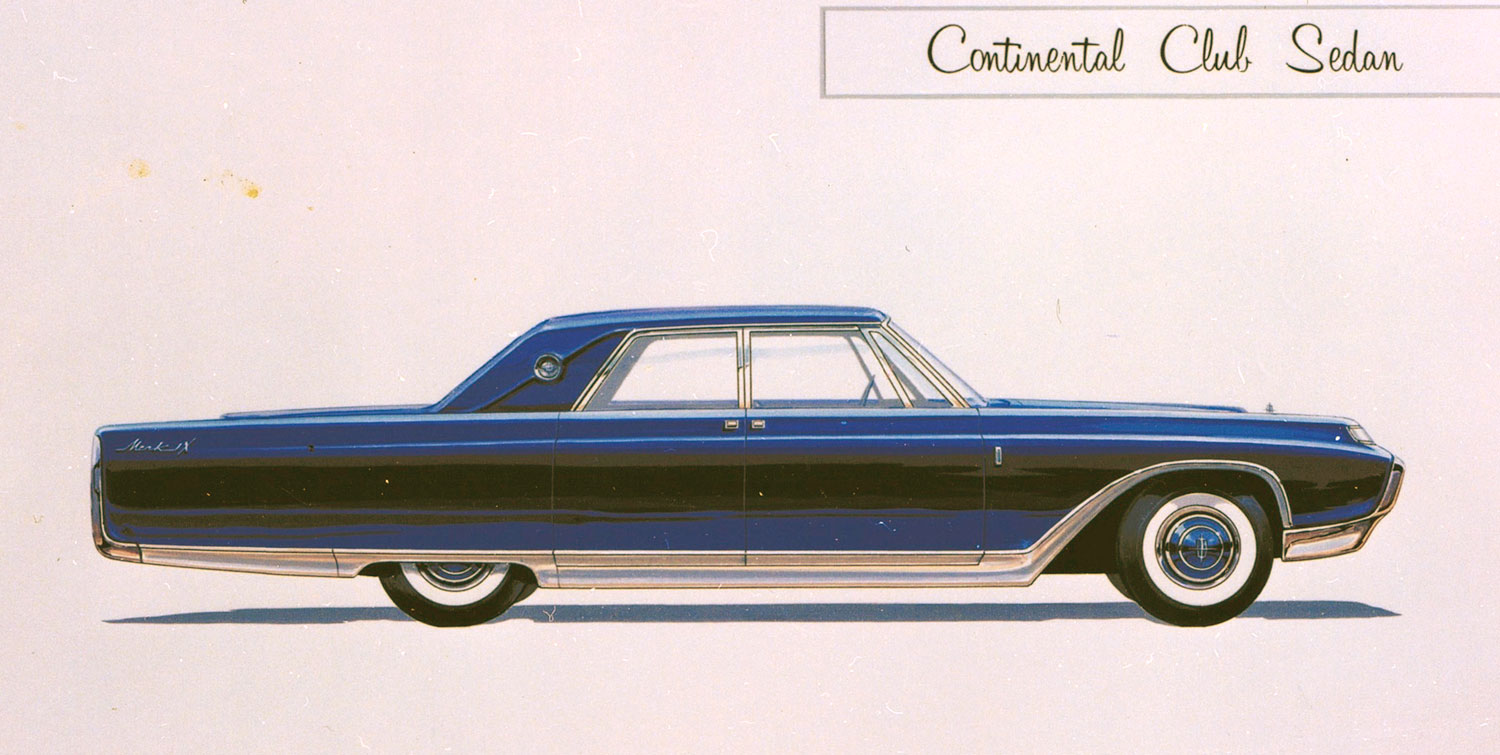

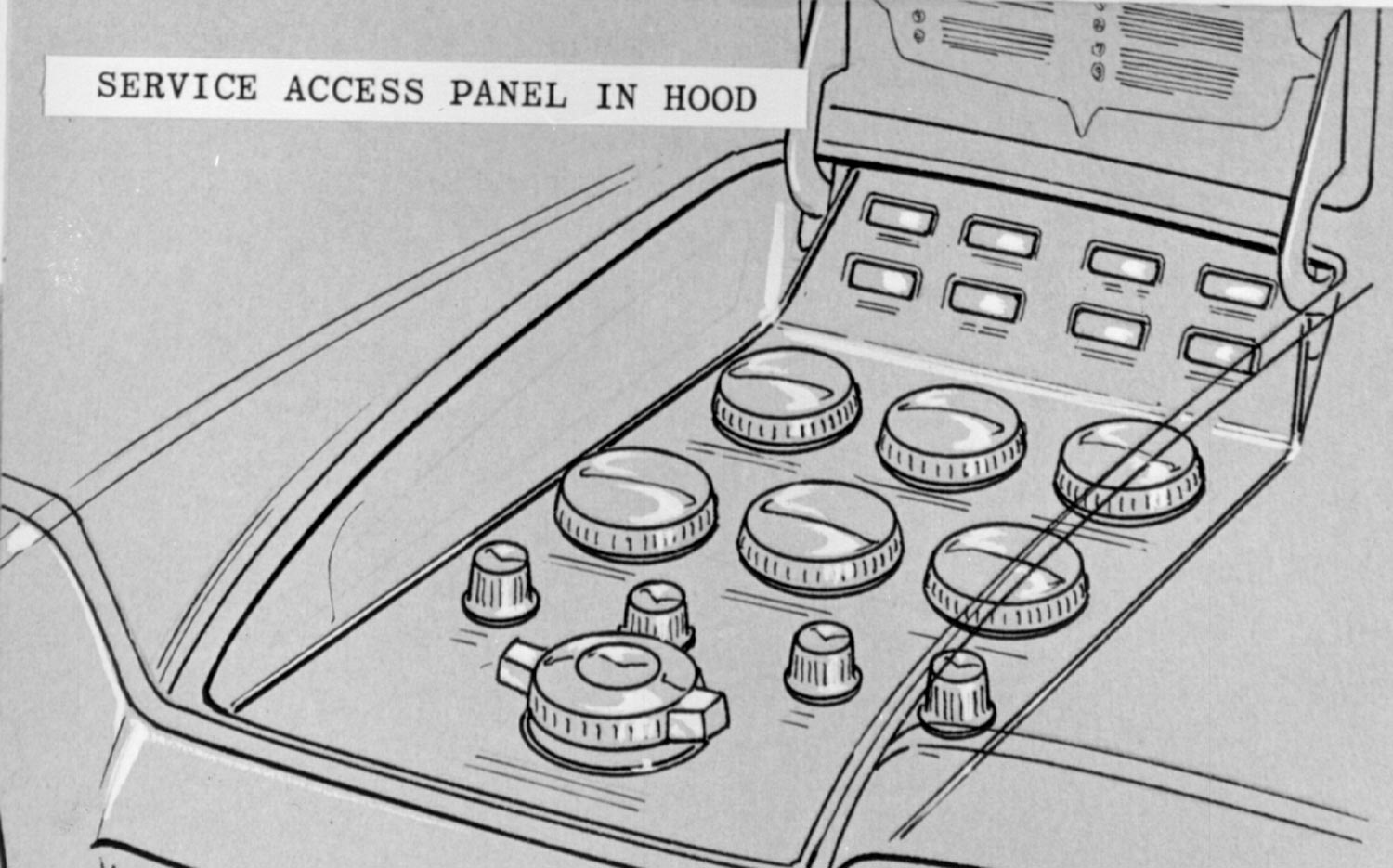

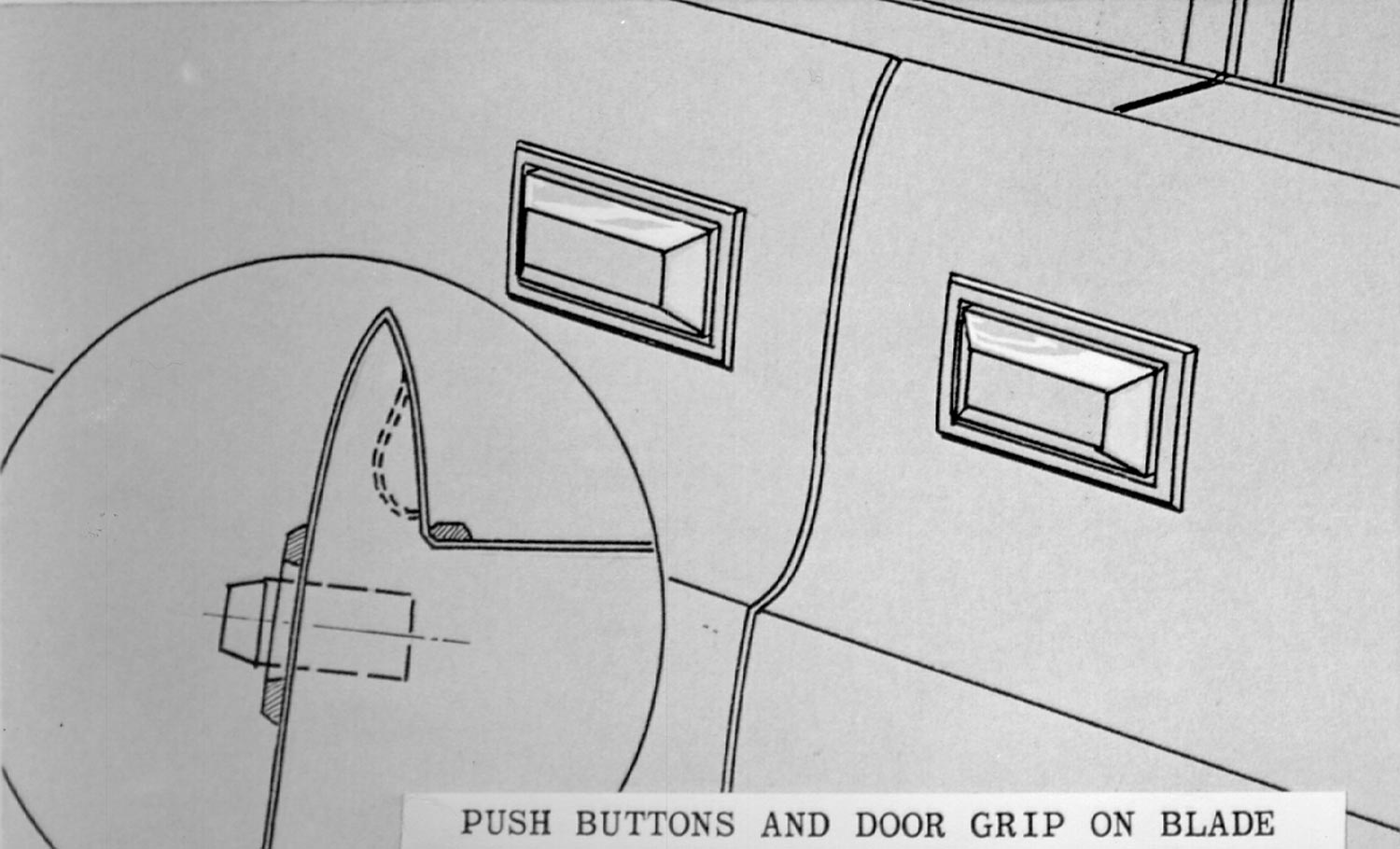

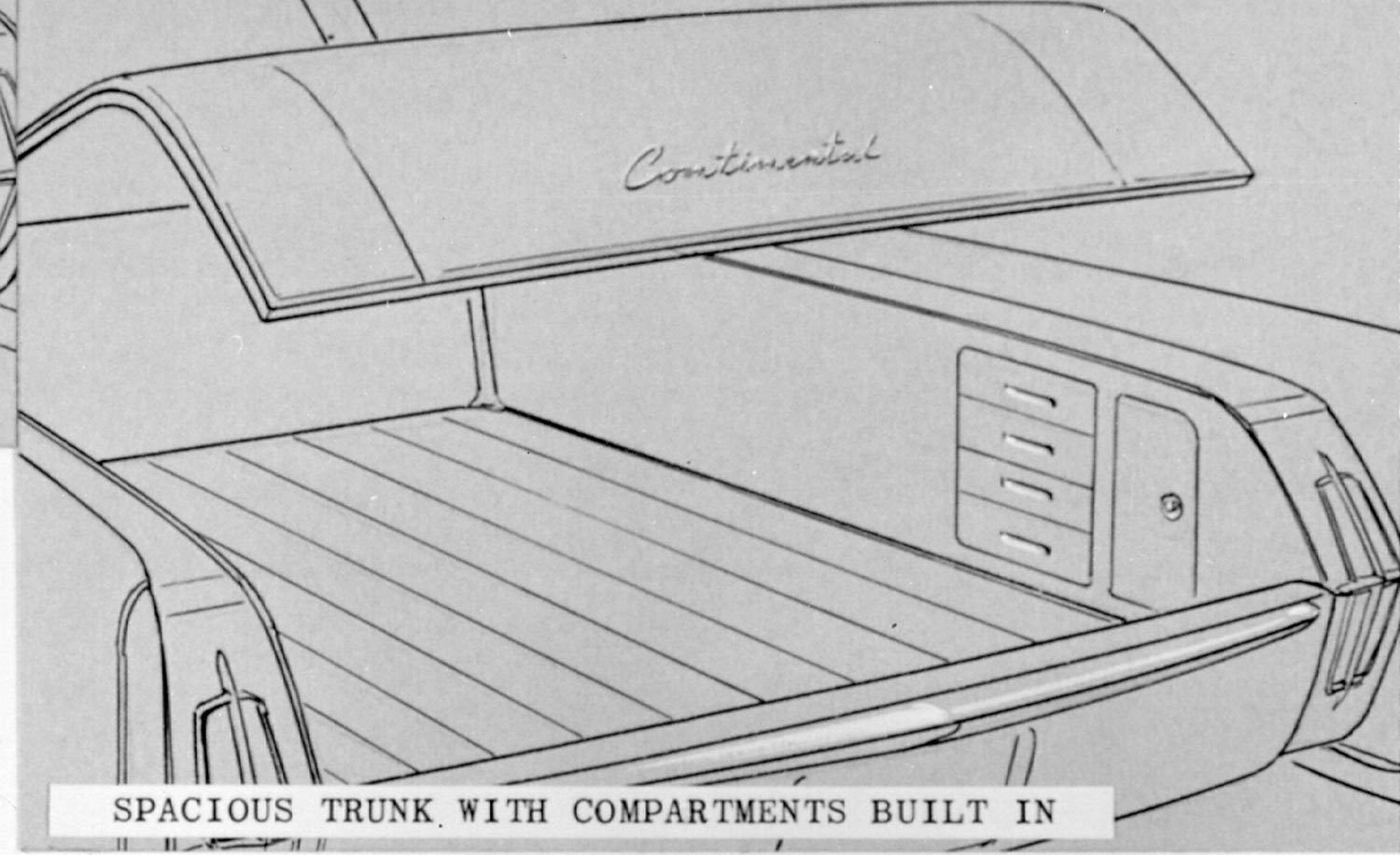

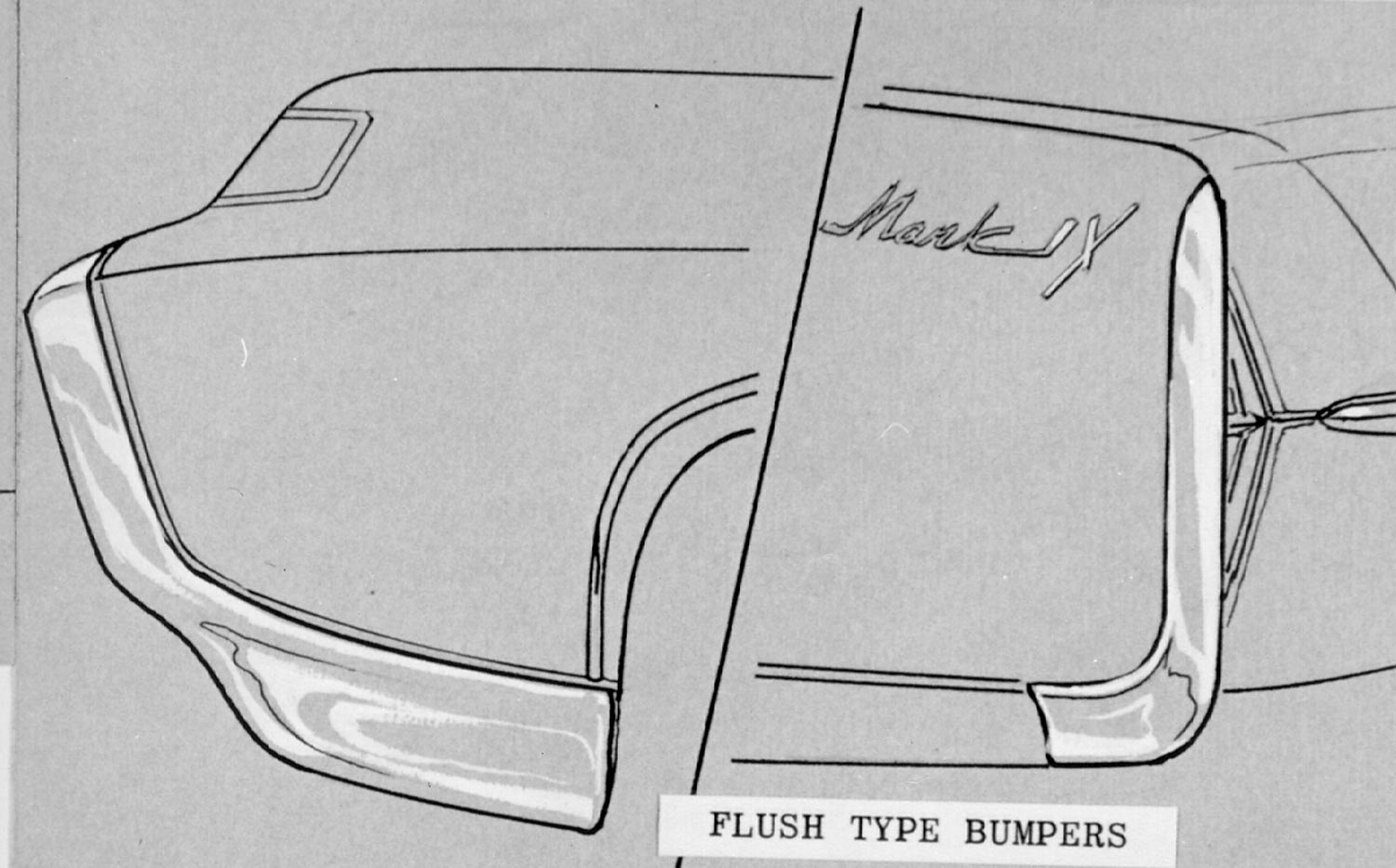

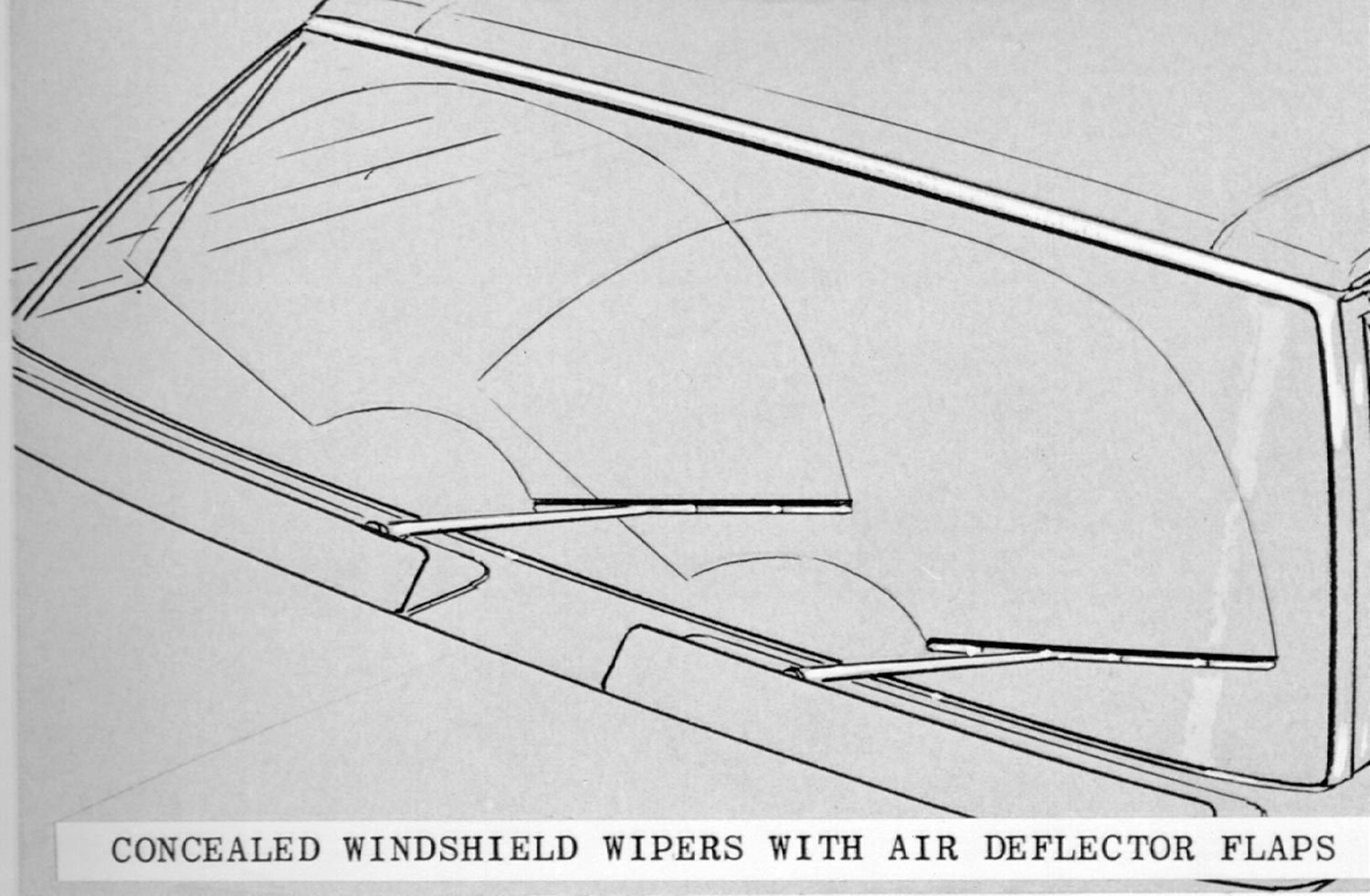

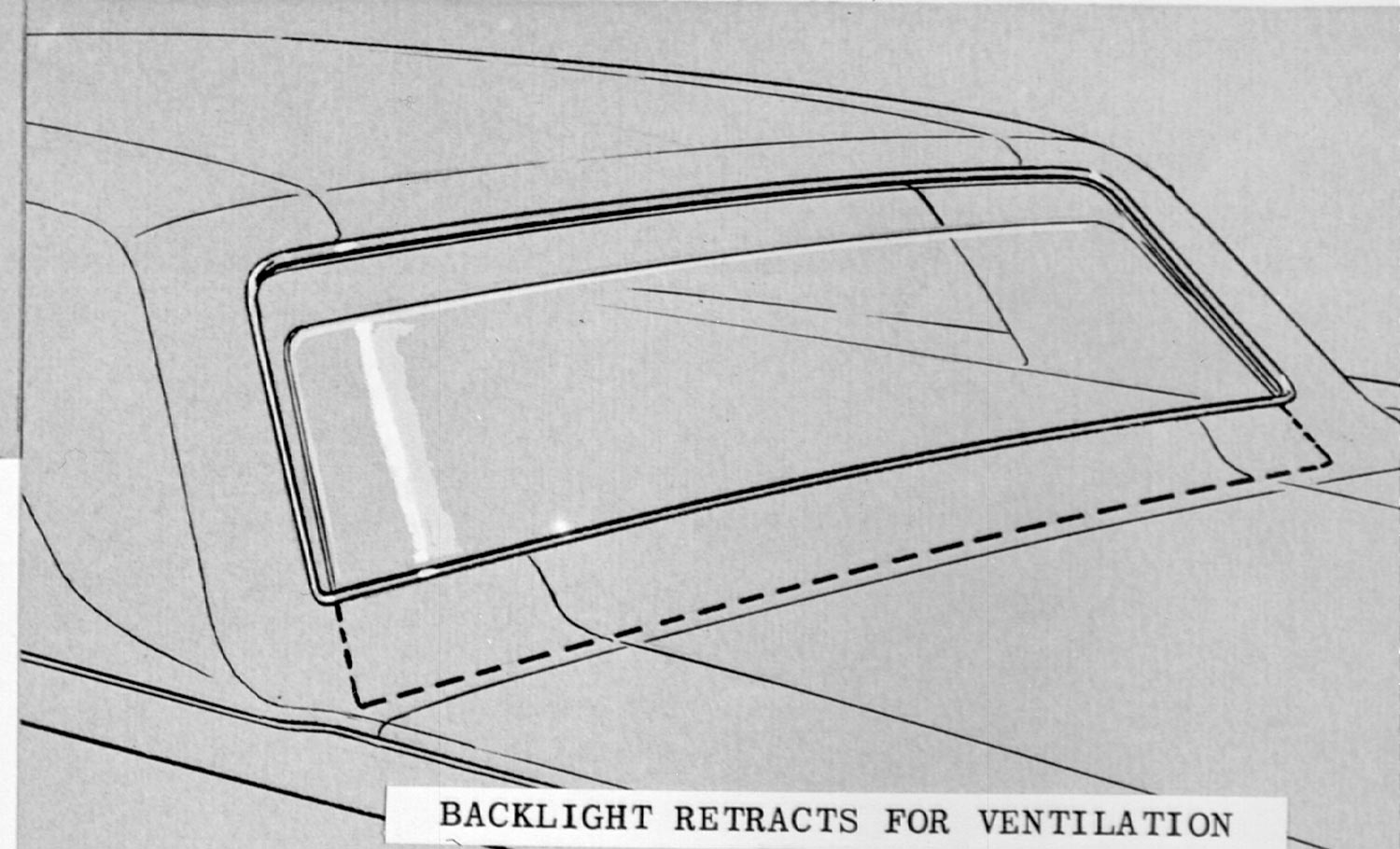

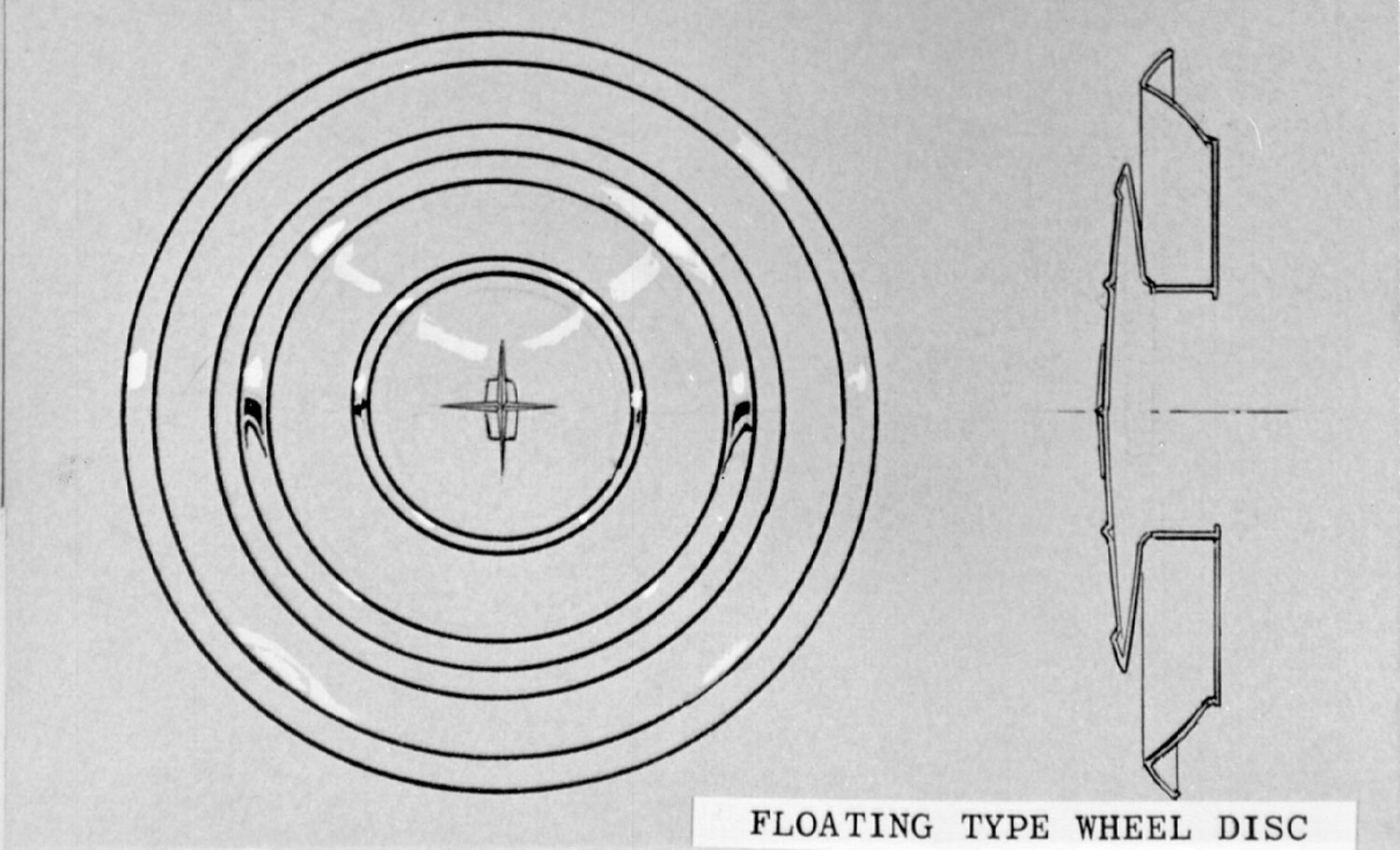

Designers of the Mark IX were Engel, Gale Halderman (manager), Colin Neale, John Orfe, Bill Dayton, and Phil Payne. Although the finished Mark IX looks longer, it is actually shorter than the ’61 Lincoln. When finished, the Mark IX was so well liked by all who saw it that Walker had designer Ray Smith install a small electric motor and steering so it could be actually driven at about 5-mph. The Mark IX was eventually built in fiberglass with four opening doors and a full interior. The special features of the Mark IX were all picked by Engel, including a small opening compartment on the hood to check fluids, a full vinyl roof that extended onto the truck, and a partially-retracting backlight. Everyone at Ford including management thought the Mark IX was a great-looking Lincoln.

Bill Ford was not a fan of George Walker. After the Mark II had been discontinued, Bill Ford became a Ford VP and titular head of Ford design. Walker, who was also a VP and head of the Styling Center, disliked Bill Ford and openly referred to him as “that f—king kid.”

When it came time to choose Walker’s replacement, Engel got caught in a scandal. He double billed for expenses he incurred during an oversight trip to Europe, which disqualified him. Walker then began supporting Oros as his replacement. Walker even told Oros he was a shoe-in, and photos were taken of Walker introducing Oros as his replacement. Meanwhile, Henry Ford II was hospitalized with mononucleosis, and Bordinat took this opportunity to present a slick-looking booklet to Bill Ford explaining why he and not Oros should become head of the Ford Styling Center, and why Bill Ford should control the selection. Bordinat also arranged to meet with Eleanor Ford, the matriarch of the Ford family, who gave her blessing to Bordinat. Bill Ford and Mills then recruited other members of Ford’s board of directors. Bill Ford even gave a fantastic speech to the board supporting Bordinat. After the board selected Bordinat as Walker’s replacement, Bill Ford must have enjoyed coming back to the Styling Center to tell Walker his candidate had lost, and his successor was Bordinat.

When Henry Ford II got out of the hospital, he agreed to keep Walker on the payroll so Walker could exercise Ford stock options that matured only after he turned 65. He also sent Walker and his wife on an all-expense paid trip to say goodbye at Ford plants worldwide. Walker was still bitter, and everywhere he went he badmouthed Bordinat and members of the Ford family, including Bill and Henry Ford II. When word of his badmouthing got back to Dearborn, Henry Ford II recalled Walker and immediately retired him. Designers report that Walker never again set foot in Ford’s renamed Design Center.

In November 1961, Walker was able to engineer Engel’s appointment as the head of Chrysler’s design department. Walker also tried to talk Oros into going to AMC as head of their design department. Bordinat had a talk with Oros. The end result was that he and Oros enjoyed a good working relationship for the rest of their long careers at Ford. After Engel got to Chrysler, he offered Neale, Orfe and Dayton jobs on such advantageous terms they couldn’t say no.

What happened to the Mark IX? Bordinat was obviously NOT fond of the car. Mills was successful in extending Lincoln’s design cycle to nine years, and the Mark IX just faded away. Besides, after Engel went to Chrysler, there was little chance Ford would produce a car Engel designed.

The next Lincoln was the 1966 Continental, which was a well-executed refresh of the ’61 Continental.

If Engel had replaced Walker as head of the Ford Styling Center, would the Mark IX have become the 1964 Lincoln Continental? Who knows. But even a retired George Walker could be very persuasive.

Photos: Ford Design

Books by Jim and Cheryl Farrell

Ford Design Department—

Concepts & Showcars

1999, 10×13, 400 pages, Fully indexed

900 photos. Includes 150+ designers and sculptors, and highlights 100 concept cars.

ISBN 0-9672428-0-0

Lincoln Design Heritage:

Zephyr to LS (1936-2000)

2021, 10×13, 480 Pages, Fully Indexed

1,600 photos and illustrations

ISBN 978-0-9672428-1-1

The Ford book is $50 plus $7 S&H (US). The Lincoln book is $85 plus $10 S&H (US). Both books bought together are $110 plus $17 S&H (US). To order, email: cfarrell57@gmail.com

How was Bordinat pronounced?

This is one of a number of corporate-involved design studio idiocies that Dean’s Garage has thankfully printed. It makes me wonder at the minimal level of adult behavior exhibited while I search for a way that any of the involved individuals ever got any work done as they seem to have endless time for personal vendettas, gripes, bad-mouthing, internecine plots and a hundred other non-work wastes of time. How these men justified their paychecks while line workers – like me – worked 8 to ten hour shifts in lousy conditions for $3 an hour or less disgusts me. That said, the actual car was quite attractive and would have been an interesting path possibly away from the lard-filled Lincolns that infested the 70s-80s to no positive good. Were there full-scale mockups of the complete interior or just renderings? And that trunk lid design is brilliant, as was the opening backlight. Was this the forebear of the Thunderbird below-backlight ventilator?

Gene Bordinat’s last name, being French, followed French grammatical rules. It is pronounced: Bor-dih-nay. When the last letter of a French word, including nouns, is a consonant and not followed by a noun is it silent – hence “‘Blr-dih-nay”

Hope this answers Tony Miller’s query.

That was a fun project and I was fortunate to have played a very minor, repeat minor, part in it. Elwood did make it fun to work on that design, but I like Bordinat’s solution better. Lucky me, I got to do a lot of work on the ’66, ’67, & ’68 Lincolns.

BOR-DIH-NAY Sorry, I typed (noun) in the effect of a noun followed by a vowel. Thereby, the letter T in Gene Bordinat’s last name is silent.

The design is long, lithe and elegant, and the rear view innovative, but that grille! Looks more like it belongs on a Dodge Coronet. And in 1970, wasn’t it used on one?

@Jay S: 1971 Plymouth Fury. From some angles, it looks a bit like a 1964 Buick Electra.

The retracting backlight found its way onto 1967-68 Mercury 4-door sedans as “Breezway Ventilation,” It was standard on Park Lane’s and optional on Montclair and Monterey. The roof overhang prevented water entry while driving. This replaced the reverse-slant retracting window used by Mercury on, 63-66 model years. (Not to be confused with the four-door hardtops which had the “Flow-Thru” ventilation first introduced on the 64 T-Birds and in 65 on full-size Fords & Mercs all with the interior/exterior vent grills.)

I think Oldsmobile got their hands on that design somehow

Well Engel moving to Chrysler explains how all those styling ques aft of the grill appear in the’65 Chrysler all new full size designs across all 3 divisions.

As much as I love the 1961 Lincoln Continental, Walker’s 1964 IX in my opinion was a big step backwards and its styling details look like predictors of many styling details that showed up on Engel’s Chryslers, Dodge and Plymouths in later years into the 1970s.

Ben Mills, one of “The Whiz Kids” of W.W.2, was one of HFII’s real heros, fixing Lincoln-Mercury from the “Big M” disasters and the Edsel, and making the difficult, yet division saving decisions after Jim Nance departed.

The tail lights, rear bumper, and trunk lid are remarkably like the 1969 Olds 98

Did this vehicle influence the 1967 Tbird four door and why is the styling story of the 67 Tbird

Not documented?

Great Article

Thank You

Well, Mr. Payne, having studied French, I beg to differ. While I agree with you about the silent last letter “t”, I disagree about the pronunciation of the “a”. In French, that is pronounced “ah” as “ay” is the letter “e” with an accent “ague” on top of it.

My father also was a French student and an economist. He admired Frederic Bastiat, the famous French economist who wrote “The Law” around 1848.

Mr. Bastiat is famous for saying “The state is that great fiction by which everyone tries to live at the expense of everyone else.” His name ends in “at”, just like Gene Bordinat’s.

I worked at Ford, in the Design Center, from 1976-1979, when Gene was VP of Styling and clearly remember how Mr. Bordinat’s last name was pronounced, as you say “Bord-in-ay”. But Bastiat’s name is pronounced “Bast-i-ah”. I even remember his special Continental Mark V with only the front seat.

I think that the pronunciation of Gene’s last name was Americanized. It was not the French pronunciation.

Did GM steal this design for Buick’s Electra?

There was undoubtably cross-pollination of design themes as a few designers would leave one company for another. But GM had the high ground in regards to styling, or thought they did. The “Not Invented Here” mindset at GM dismissed styling themes “borrowed” from one studio to another, let alone from Ford or Chrysler. The idea was that if GM didn’t create it, then it wasn’t any good. In fact, if a designer had worked for Ford or Chrysler, he was disqualified from working at GM Design.—Gary

I concur with Mr. Duvall’s observation regarding the Mark IX; in the comparison photo of the model parked next to a production 1961 Lincoln convertible, the design was neither as clean nor as distinctive as the previous car was and appeared to borrow from other brands in production at the time. The article mentions a lack of visual heritage from Lincoln (and assumed Continental) models, but there are references to the Continental Mark II visible in the treatment of the taillights, the roof sail panel and the proportional offset of the roof to lower body, as well as the textures chosen for the grille and ‘faux’ grille in the decklid. Mr. Engle’s Ford experience would be visible in one of his first “marque” projects at Chrysler: compare exterior views of the Ghia turbine car to the Thunderbirds done under his leadership. As one of my closest friends used to say, “everybody’s got one design”.

When I saw the lead in photo of the Lincoln I thought wait that’s not a Lincoln, that’s an Imperial. That is where I believe the story goes…

Yes, there actually is a lot of Mark II in the 1961 Lincoln. The ’61 roof was intentionally recalling the two door hard top Mark II. The suicide rear doors weren’t just cool but necessary given the short rear side window and wide C pillar more appropriate to a two door car.

I think the idea that the Lincoln was originally a Thunderbird proposal is always overplayed. Both follow style elements of their predecessors in all kinds of ways. I’ve seen claims that the windshields are the same but actually the windshields and entire cowl (the Tbird is lower, narrower and has non-parallel wipers) and HVAC are different. They did both end up with unit bodies with a lot of engineering in common (like the original 1958 unit bodies) but actually were pretty much completely different despite claims to the contrary.

There’s a little of what ended up in later Marks and Thunderbirds (mainly the retro references) in the 1964 proposal and a whole lot of what showed up in later Chrysler products (and a little in Oldsmobiles and Buicks). It’s the 1970 Coronet that wears that front end, and the side shape and rear end is in the big 1965-on Mopar products particularly Chryslers and the unit body Imperial. And compare the rear of the 1961 Thunderbird to the front of the Turbine Car.

And I thought Chrysler, Plymouth, and Dodge were ugly!