Automotive Design Oral History Project

Interview and Reminiscences of George Krispinsky (GK) including a few samples of his studio artwork, and a short video (about the origins of Ford’s retractible hardtop) taken during the interview.

This interview is part of the documentary currently in production: “American Dreaming; Detroit Automotive Styling 1946-1973,” a film by Greg Salustro, Bill Porter, and Robert Edwards.

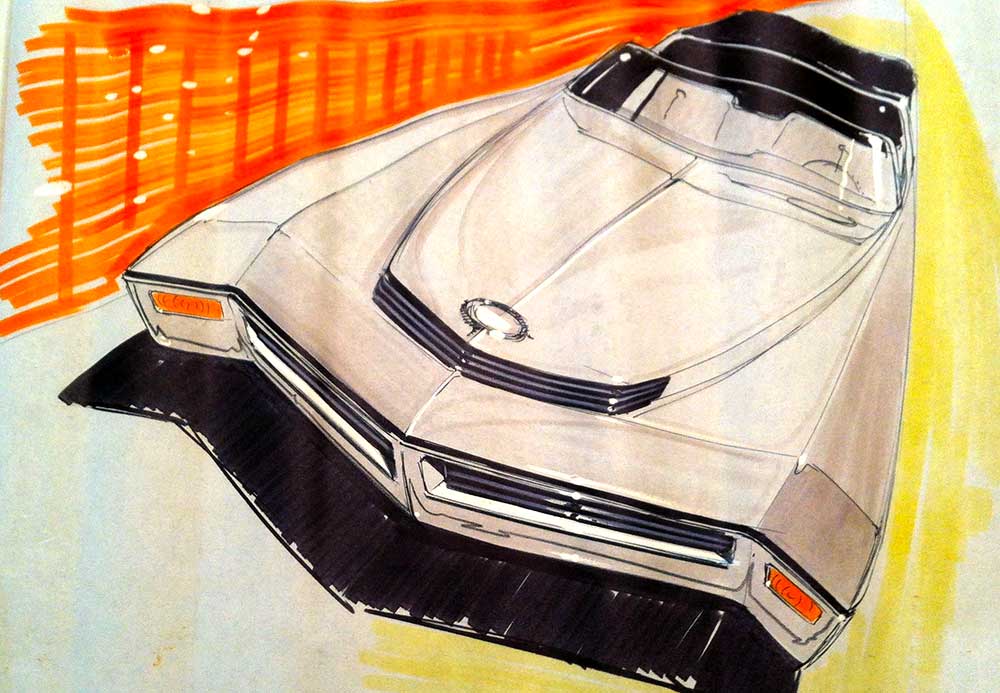

1966 Dodge Dart proposal by George Krispinsky

On June 19th, 2013, Bill Porter (BP), retired GM automotive designer and historian, and Robert Edwards (RE) of ModernMadeVintage.com, a Detroit-based dealer specializing in mid-century, industrial and automotive design, sat down with retired automotive designer, George Krispinsky.

Mr. Krispinsky began his career in 1950 at Ford Motor Company. In the mid 1950’s he was hired at Packard Motor Company and became it’s Manager of Exterior design. After the demise of Packard, he designed for the Plymouth division of Chrysler. By the middle 1960’s he was at AMC later becoming Exterior Design Manager there. Mr. Krispinsky was instrumental in ushering in the era of the SUV with the Jeep Cherokee. His accomplishments are many, and we are pleased to have him tell his story.

RE: Mr. Krispinsky, please tell us where and when you were born, about your youth and your years at Cleveland Art Institute?

GK: I was born in Youngstown, Ohio in 1923. I attended parochial and public high schools there, and after I graduated from high school I had a job for a short time as a beginner—an apprentice, actually, for Architectural Drafting at ten bucks a week. How do you like that? If I stayed there for a few months it would have been twenty-five. Anyway, I left there after a short time.

I worked in a department store where I sold wallpaper, and after that I worked for Trustgon Steel for a while. And then came the Army time. I went in the Army in 1943 and served three years in the service, two of which were overseas in Europe. And I was one of five brothers who served in World War II.

One was seriously wounded in Africa and the other was wounded in January of ‘45, later he was killed just before the war ended in the Pacific. So, anyway, when all that ended I get out of the Army, and I was available for the GI Bill of Rights, which paid tuition plus 75 bucks a month subsistence allowance.

So I applied at the Cleveland Institute of Art, and I was accepted there in 47, I believe. And I finished a four-year course in three years. I graduated in 1950. My instructor there was Viktor Schreckengost and he was the head of their industrial design department, which was very small.

RE: Did the Cleveland Art Institute have a strong design department? Viktor Schreckengost was a very famous ceramic artist as well, as a designer. Did you get a lot of inspiration from him?

GK: Oh, yeah. Yeah. He was instrumental in doing artwork, and—yeah, he was a good designer, well known.

RE: Did you think of yourself after college as first an artist and then an automotive designer, or how did you perceive your entire career in terms of that?

Studio Design Work by George Krispinsky

GK: I was interested in drawing and buildings model airplanes. Bill probably did, too.

BP: Yeah.

GK: And at first I thought I’d like to be an Aeronautical Engineer, but I was terrible at math.

BP: That’s exactly the same thing I had in mind. I saw the math and decided otherwise.

GK: Well, anyway, I decided to enter the art school and find out what that was all about. I always liked to do portraits, for one thing, and I was always drawing one thing or another. I never took art in high school because I didn’t think I’d get involved with it professionally.

So, anyway, I wound up going to the school of arts, Cleveland Institute of Arts majoring in Industrial design. At that time I didn’t even know what industrial design was. But I soon found out, and I figured that this is right down my alley and best suited for my talents and my interests.

So, when I graduated from the Art School I started working for Ford in 1950, and I worked for a guy named Gill Spear, who was a hell of a nice guy, and all the beginners started there. And I went to the Mercury exterior studio under Bob Wylan, both Gill and Bob were the nicest guys you ever wanted to meet. And I had a job offer to go—I forget where it was now, and they offered me a 15% raise, which was unheard of, you know. And I said, gees. So like a dummy I made a bad move. I had recently been married. And I went to Chrysler for couple hundred bucks more a month. Like I said, I sure—I always regretted that move.

RE: Was the atmosphere at Ford that much better or why did you regret the move?

GK: Well, I didn’t know what atmosphere existed at Chrysler, but I liked the old Ford. I don’t think it’s that way anymore. You know in the ’50s it was a lot looser and you get more directly involved. Now I guess there’s so much red tape you wouldn’t want to bother with it.

RE: So how long did you stay at Ford?

GK: I was at Ford for three years, went to Chrysler where I worked in Plymouth for a while and later Dodge Studio with Herb Wisinger. And Bill Schmidt at that time was starting a designing department at Packard. And so I thought what is the chance I couldn’t pass it up as manager of Packard exteriors. I’d only been in business for five years at that time, you know, but it was a big break, you know, to learn the wares and what forth for management. And let’s see, I guess that’s it.

RE: And how long were you at Packard as a design manager for the exterior department?

GK: Approximately, two years until they folded. And that was a sad time.

RE: Did you work at the Boulevard Building?

GK: Yes. Yeah. That’s still there somewhat.

RE: Now, one of the stories that’s been passed around was the destruction of all of the automotive design files at Packard when they were closing it up. Were you there? Did you witness that?

GK: That was after I left.

RE: You were gone.

GK: And I think (Dick) Teague managed to grab a few beautiful illustrations before everything collapsed. And I guess a guy named Churchill was involved with Studebaker at the time. He was President, I think. And he said, now this is hearsay, you know, that he wanted any record of Packard destroyed. You know, what a jerk. Anyway, it’s too bad just beautiful stuff destroyed by a real, I don’t even want to say the name.

BP: Yeah.

GK: But, anyway, that’s the story I heard. It’s probably true. From what I understand there were a few things taken to the Detroit Public Library and left there by, I think by Bill Brownlie.

RE: Have you heard that story, Bill?

BP: No, I haven’t. I don’t know anything about that—but Sparky did tell me that he worked at Packard before he came to GM, and I was aware of that. He never mentioned any artwork being destroyed. I don’t know. It just never came up in our conversations.

GK: I never heard of it either.

BP: It’s a horrible idea, of course. It’s a terrible idea.

GK: Of all the places.

RE: Now, after Packard you moved to over to Plymouth? Is that correct?

GK: No, I moved to Dodge Studio with Herb Wisinger, and later on I worked for John Schwarz. Those are some bad years for me my work was going down hill and my interest was being lost. And I didn’t like John Schwarz, and he didn’t like me. But that’s not too bad; nobody liked him.

BP: Now, he was a Chrysler guy, John Schwarz?

GK: Yeah.

RE: Now, when you were at Ford, did you ever meet George Walker?

GK: I did.

RE: And how was he to work with?

GK: I didn’t work with him directly. In fact he offered me a job and I didn’t want to work for a small outfit. And he had his Elwood Engel and Joe Oros they were Walker guys. And Walker evidently had some influence and he got them into Ford, Ford designing

RE: During your career you worked with people like George Walker, Virgil Exner, Bill Brownlie, Dick Teague, Elwood Engel and of course Bill Schmidt, who was a good friend of yours. You worked with him for a long time.

What are some of the other colleagues you had and what were some of your favorite relations with these designers? Did you have close relationships with anyone in particular?

GK: Not really. You know, a lot of long time friends, but we weren’t that close. When I was at Chrysler, I did a grill for I think it was a ’59 Plymouth which is kind of hokey. I did some designing rather that styling. But with this grill my intent was to stamp this and have it corrugated with slots and that to become the grill. And, you know, you draw anything and they die cast the darn thing with—as Bill knows, some of the GM stuff, you know, 50 million parts and pieces. Well, my idea was to eliminate a lot of that and do a relatively inexpensive stamped gold plated grill. Some of the designers kidded me about that. And called it cabbage grater, all kind of stuff. Anyway what I liked about it is I design it not just styled it, you know, it was my idea concept to finish. And it became a laughing stock to a lot of designers.

RE: But isn’t later on in the ’60’s grills like that started to became more common when they were sort of more sculptural and not just bands or rods, and then they were stamped in particular like in ’63, ‘64 some of that stuff started to come into play?

BP: For a while in the mid ’60s I was at the Tech Center Studio number 1, and we put a tremendous premium on that kind of thinking. You know you can do a stamping that is very handsome and attractive and catches the light in the right way and so on versus the casting then you’re a hero because you just saved lots of dollars and on a low-priced high-volume cars like Plymouth or, Chevrolet and that means the difference between profitability or lack of it. So, that is important. I know exactly what George means with that grill.

RE: Okay. Do you recall what late Chrysler that would have been on? I can’t seem to recall.

BP: On the ’59 Plymouth. And it would have probably—Chrysler was using die cast grills because they were more expensive and higher quality they looked better close up and detail was finer, finer detail.

RE: As I mentioned there were several drawings late 1950s era where you were working on the Plymouth Fury, in particular, and there were some rear end treatments without—and you were trying to move away from the fins and this would have been for the ’62 model year, but this wasn’t the downsized Plymouth that they ended up becoming.

BP: I did print out some of these. Here’s, now, there’s several here getting away from fins.

RE: Yeah. That was a big transition from Exner’s big fins and the gun site that he was trying to develop.

BP: I don’t remember the exact years. Here’s a car without fins for instance, another one.

GK: Yeah, yeah.

BP: Here’s a few drawings, I guess from the late ‘50s. Here are some with no fins but these raised tail lamps, independent tail lamps. Let’s see, I had another one in here, too, that I thought — yeah, this one here.

GK: What was that last drawing?

RE: That was the AMC (1967 AMC Armitron) concept.

GK: Yeah, yeah, I made that drawing.

RE: You made it?

GK: Yeah.

BP: Yes, I thought it was yours. I thought it had your touch. Here’s another Chrysler car. This one has sort of finished fins.

GK: Yeah.

BP: I wouldn’t call them exactly fins.

GK: All you’d have to do is squash the deck lid down where you lose so many cubic feet of storage space.

RE: There’s the one with the Exner tail lights with horizontal instead of vertical fins.

BP: Yeah, yeah. There’s another one here, I thought I had it, guess maybe I didn’t get. Here’s the one with those extra tail lamps up high, that’s sort of a horizontal fin instead of vertical.

RE: But it’s dated ’62 on the license plate there. The drawing was done in ’58.

BP: It was done a several years earlier.

GK: Yeah.

BP: And this one I thought, you know, obviously has fins that are rounded down and off.

The Origins of Ford’s Retractible Hardtop

RE: Can you tell us a little bit about your designing methods? I mean, how did you imagine these things? What were some of the inspirations you had, George, as you were looking to design cars?

GK: It’s hard to really put your finger on something like that. You see what’s going on and you decide to either not do it or try something better or whatever. You usually try to clean it up quite a bit. But, as Bill will tell you that some of the ‘50s and ‘60s Oldsmobiles and Pontiacs they had more chrome on their sides than they did on some entire cars. You remember the Oldsmobile with all the chrome all over. That was Harley Earl’s day. Right, Bill?

BP: Exactly. Especially toward the end of his career. He just fell in love with these elaborate chrome fins and so that’s what he demanded and he was the boss.

GK: Well, I guess he was quite a boss.

BP: He was indeed.

GK: I guess Bill Mitchell got rid of a lot of that.

BP: He cleaned things up the first few years of his career.

RE: George, during the transition period in the late ’50s to the early ’60s with Exner existing from Chrysler, and Bill Schmidt and Elwood Engle sort of jockeying for position there, did any of that personal animosity that’s been reported between them did that effect the designers at all or was that all close door?

GK: No, it didn’t. I remember Bill Schmidt wanted this is on a Plymouth, particularly one fin in the center of the deck. And that was terrible. Now, here they’re modeling this thing full size, and I made a cartoon of that thing where you lifted up the deck lid and there was a tail of an airplane in there with rudders sticking out. I don’t know if Bill ever saw that. If he did, anyway, you know, even guys like that screw up. You know, it was a terrible design. How he ever had the manpower to do that, I don’t know, but he was the boss at one time.

I don’t know if Bill left because he didn’t want to give up his industrial design firm or not, that maybe part of it, but I think that there wasn’t room for Bill when Exner came back and then eventually Engle, Elwood Engle.

RE: And during your career, what were your relationships with some of the modelers and engineers that you would also have to work with?

GK: Oh, I had a good relationship with the modelers and engineers especially at American Motors where things were small, not a lot of red tape. You were on your own. If you had a problem with engineering, in my case usually surface engineering, and I would just go up to see Wally. Can’t think of his last name now, and he was the manager of exterior surfaces. And I’d go up to him and we would resolve this problem right then and there and not get involved in the typical big three stuff. You know, where they have a meeting and meeting and your boss didn’t want to make a decision so he calls his boss, and on and on and on and you get this big red tape bullshit. Right?

BP: Yes, absolutely.

GK: So in that sense AMC decided to, you know, operate pretty much the same way that the big three did. Although like I said, it was compact and you could work directly with the engineering department or staffing people and resolve it right there. No, you know, boom that’s it. Let’s do it. And I liked that.

BP: Did Dick Teague encourage you to do that?

GK: We just did it. You know, it got done and he was happy. He didn’t want to interfere too much with that sort of thing. So I kind of really enjoyed that liaison between engineering and styling. Even at Packard I enjoyed working with engineering.

RE: Is there any modelers or engineers, offhand, anybody in those departments that you particularly thought was really good or you had a good relationship with like it terms of modeling were just like really true artists or were they all equally good?

GK: Yeah. Well, I think I mentioned in one of the Stew Bonds periodicals, it’s the business of sculpture, you got to think in three dimensions and the way to prove your sketch out in clay is to, you know, make it a piece of sculpture. And that’s essential the proof of the design you can sketch all sorts of things nice things, but how’s it going to work three dimensional, you know, so. Lot’s of time there’s a conflict and lots of time the basic idea maybe impossible or improbable to make because stamping problems and die cast problems, money, you know, that sort of thing. And so there are restrictions.

BP: Did you ever actually pick up a clay tool and get into the modeling yourself to kind of convey your ideas to the modelers? Did they let you do that?

GK: No, because American Motors modelers were union and at Chrysler the modelers were union.

BP: I knew they were at Chrysler.

GK: I remember once I forgot myself, but I just started doing front end work on a three-eighths scale model and this modeler didn’t say anything, and I caught hell for doing it. Anyway at American motors that was extremely difficult because the designers and the modelers were unionized. And that presented a difficult problem. It was bad enough dealing with the modelers who were unionized, but the designers were unionized. Anyway, it made it more difficult you know.

RE: I’m curious, you know, there was a short period of time when Chrysler’s Executive vice President, William C. Newberg, ordered two shifts for the designers because he overheard that General Motors was.

GK: I never saw that.

RE: You never?

GK: We just worked overtime.

RE: So that’s sort of a stretch of history there when that’s been recorded.

GK: I don’t remember anybody doing that. Not at Chrysler anyway.

RE: Okay. Well, that’s good to know. Because it is in a book and I forgot the name of the book. I should have brought my reference material. But it was an interesting story and it just seemed something that I wanted to learn more about, but I guess it’s been disproved.

In the early ’60s imported cars started to become more popular. What were your thoughts on the imports in the ’60s and in terms of design and engineering and how was that affecting American car company studios?

GK: Well, we obviously were aware of what was going on and we didn’t have any good spy system so we didn’t know what the competition was doing. But there were hints, I guess, guys talk. You had a pretty good idea of what was going on. Although, we weren’t likely to be followers of any design, philosophy or theme. So, we’re pros on our own.

BP: I have an ancillary question. Did you ever work with a guy named Art Kibiger at American Motors?

GK: Sure.

BP: What was your role relative to his, or what was his role in the company? I’ve heard of him, but I’ve always wondered what he did.

GK: I think Art was a tech man more than anything. I don’t remember him doing any design work.

BP: Was he like the studio engineer or kind of a concept thinker?

GK: Something like that. I don’t know his exact title.

RE: Now you mentioned a minute ago about the spying or snooping trying to figure out what the other designers were doing at the other firms. How prevalent was that in the 50s and 60s? Do you have any interesting stories to relate about catching wind of something?

GK: I remember seeing photographs of the exterior design studio taken through venetian blinds. Somebody must have been out there on a telephone pole or big tree. I couldn’t believe it. Somebody is out there with a telephoto lens, you know, taking pictures of what we were doing.

BP: Wow.

RE: In what year in the ’60s did you move over to American Motors?

GK: ’73.

RE: ’73 to AMC? There’s a drawing from your collection, there was an Ambassador from ’67 that was signed by you. Are you sure it wasn’t earlier?

GK: I didn’t work on the Ambassador at that time.

RE: That’s interesting.

GK: I think Romney was there at the time and that series of American Motors cars wasn’t exactly a fantastic styling success, but they sold the car. Romney was there. He pushed fuel economy and other items. In the end they were pretty good cars. They weren’t really styled that well, but they were good cars. Which means if they were selling it was a heck of a success.

BP: Sure. Kept them alive.

RE: Do you have any questions, Bill, to follow-up on that?

BP: Not really, but did you work on any of the compacts then or was that or were they done before you got there? Like the early Ramblers were all ready done before you got there, right?

GK: Yeah, that was already done before I got there. When I got there they were working on Renault, the French company.

BP: Sure.

GK: And I was working on the federalizing the components on the Renault products. In other words, making them legal by our standards. And that was, you know, interesting. Not a heck of a lot of work.

RE: Now, your design office was at the old Plymouth Road office complex. Is that correct? Was it always there? Did you move over to the new building in Southfield? Were you always at the Plymouth Road complex?

GK: Yes.

RE: Some of those designs from the late ’60s, particularly the Javelin, the AMX and the Gremlin, what do you think about how those designs held up? I personally think that they’ve held up really well, and I think they’re really nice.

BP: I think so to.

GK: Those designs the AMX and Javelin were built by one of the big three it would have been a howling success, and I think the quality would have been a lot better. So, American Motors products suffered from quality problems. I know I had a Javelin and it was rusting out quicker than you could imagine and that’s not good.

RE: Yeah. It was a pretty car. Bill, I’m going to ask you a question about that too since you were designing at GM at that time and I’m going to catch you little bit off guard. As you were looking at the AMC products at that time particularly, again, the Javelin and AMX, I thought they were really beautiful cars, what was your thoughts at that time and did people at GM take note of what was happening in those AMC years?

BP: Oh, I think that one of the situations at GM, which is true in that period, was that the internal competition at GM was so intense that they tended not to look outside their corporation a lot. Although, those of us who were designing new perfectly well that the Javelin and the AMX were good looking cars.

GK: Yeah.

BP: Nobody disputed that. They were very handsome cars. They look great on the road. They were fine, and they still look today. They’ve held up very well. But I was in Pontiac at that time, and I was worried about what was going on in Chevrolet down the hall. I wanted my Firebirds to beat their Camaros that I didn’t really look at AMX or anybody else that much. I didn’t even take a look at Ford, because, you know, Chevy was right in my face. And I had to beat them or wanted to beat them and that was just sort of the spirit of the place. It was a little different.

We had some security problems. But that was our situation. It wasn’t that we didn’t think they were good. We did. We thought they were great. But my problem was the Camaros were out selling Firebirds two-to-one and the Pontiac dealers were screaming and hollering, you know, so, yeah.

RE: Now what was your relationship with Dick Teague? I know that you work briefly together briefly at Packard as well.

GK: We worked together at Packard and again at AMC. At AMC he was VP in styling. At Packard he was director of design for Packard. Bill Schmidt at that time was the VP. I think the VP didn’t particularly like the idea of Bill coming over with his all the entourage and people from different places including me. And so the people at Packard at that time didn’t like the idea very much. You know, a whole knew crew coming in. But, I mean, they gave Bill Schmidt money to even the air condition the place. Guys in body engineering, it was so hot in there they were working stripped to the waist. And a lot of the managers would they’d come in to see me just for the hell of it. They wanted to get cool, you know, but that was some of the problems at Packard. Our facilities deciding some of these things spent a lot of money developing—we were relatively happy in that environment.

RE: What year did you become manager of exterior design at American Motors? Were you hired in as manager of exterior design?

GK: I forget what year it was. At that time I was hired to be supervisor for Bob Jones who was the manager of exterior design at the time. And Bob had terminal cancer at the time and passed away, and I think Dick (Teague) wanted somebody to replace him which I eventually did. And, again, these guys were too happy, you know, I was jumping into a proverbial fire.

BP: Yeah, I can understand that. You were kind of in a little bit of a difficult position. You were kind of between a rock and a hard place.

RE: Your business relationship with Bill Schmidt going back to the Packard/Studebaker years, as well, it’s been said that he refused to quit doing his independent work, as you mentioned earlier, that he was passed over after Exner and before Elwood Engel eventually took over Chrysler.

There are examples of work that you did for Schmidt’s firm in the ’60s and early ’70s at William Schmidt and Associates, how long did you do freelance for him during your career? Was it just periodic or sporadic?

GK: I was hired there. I was an employee. And I worked there, I think, 6 years I believe and the big project I had was major contribution to designing the taxi cab, futuristic taxi cab for US Steel. And US Steel during that era was spending a lot of money for this sort of thing. And that was fun from beginning to end to see it and eventually take a ride in it.

In fact, I had to follow the thing all over the place and get it painted and take it down to Cobo. There was a place on Woodard in Ferndale (probably Northwood Collision) these guys were pretty good painters. So I had the guy, with a truck, car transporter, drove the taxi up on the truck. And he pulled it up in front of this paint shop, half of the truck on the left side was on Woodward and the other half was on the sidewalk. And this guy backed that thing down there and it was going like this—(holds his hand up in a tilted manner).

BP: Oh, my Gosh. That must have been terrible.

GK: By God, if he had turned it over, it would have been awful.

RE: Wow.

GK: But, anyway, he got it down safely. It got painted. They did a good job.

BP: I have a question for you in connection with you as your involvement with Schmidt and US Steel. Did you have any dealing with Syd Mead who was doing some illustrations, a California guy, illustrators, their technically illustrators, did work for US Steel at that time?

GK: No, no. He worked directly for US Steel doing vehicles.

BP: A lot of futuristic stuff, yeah.

RE: What can you tell us about Schmidt’s design philosophy when he lead his independent work? And I also noticed that in yours drawings there was something that looked like the Stutz Bearcat, an early ’70s car, of course, that Exner originally designed, but it looked like an updated version of that. Do you recall seeing that, Bill, the front end looked like a Pontiac Grand Prix, but it turned into something more like a limousine? I don’t have a picture of that with me. But did you do that for Schimdt?

GK: No. I don’t really recall anything like that.

BP: Was that during the year of the Packard Predictor or am I in the wrong decade here?

GK: It must have been before because after the Predictor and the ’57 Packard that was the end.

BP: Did the Exner car that he might have done for the copper industries because he did sort of a neo-classic car after he left Chrysler for the copper industries, and it had copper cladding instead of Chrome.

RE: It was called a Stutz Bearcat. It was produced for about six years and a lot of entertainers liked that car in the early ’70s, and there’s a couple drawings that are in the sale that show those drawings. It was as if they’re working on a limousine version of that. I think they had a coupe, and they had a sedan, very few sedans, but this is more of a limousine version of that.

BP: I don’t remember that, but I do remember a later Duesenberg proposal that Exner did.

RE: Now, George, you were really important in the birth of the SUV era. Did you have any idea when AMC was down sizing the Grand Cherokee and make it more of a family oriented vehicle what big of an impact it would have? And it really was the savior of AMC Jeep for a while.

GK: When they decided to down size to get rid of the original big Cherokee and so forth, I was in on the beginning of the styling of it. I can’t think of the names of the engineers that were responsible for packaging this thing, but he wanted to employ a lot of aerodynamics on a big Jeep.

BP: Well, good luck.

GK: I remember I had the modelers do a part of a front end with sloping fenders, and that’s the sort of thing you just don’t do because it’s essentially an on-road/off-road vehicle. But it proved to him that it wouldn’t work.

Anyway, but you could just do so much for Aerodynamics. Although, we did take a model over to U of M—they had a test tunnel, a wind tunnel, and they’d put these little bits of yarn all over so you could see which way is flowing and where. And it’d give you a pretty good idea where we could tickle something here a little bit there, a little bit there. And it was easy to compromise some of those things to a degree where you couldn’t do anything very drastic to help it aerodynamically, and so you had to pick little bits and pieces all over the place which meant a very minimal change in the styling and things. So, that was kind of interesting.

RE: When AMC Jeep was purchased by Chrysler, did you know that it was in the works or did it catch you by surprise?

GK: No. We heard that it was coming. And of course they bought it strictly for Jeep. They didn’t care about anything else. By the way, nobody mentioned the Pacer.

RE: Oh, that was a great car. It was much maligned in my opinion. What do you think about that?

GK: Well, the concept was okay, but I think the fact that they wanted to make it a luxury small car was a big mistake.

RE: Was that Teague’s idea to make it a luxury car?

GK: I don’t know. He did the original design. Jerry Meyers, their President, who wasn’t a car guy, evidently, it took him quite a bit to do this, and they decided to make it a luxury car. I wasn’t there during that development. I was there after when they started doing a wagon version of the Pacer, and it was way too heavy. The passenger door was a lot bigger and heavier. I know when I drove one up our driveway, which was on a slight incline, my wife couldn’t open that door it was so heavy.

So at the Monday morning quarterbacking had they stuck with a philosophy more like the American version, a light small car, maybe, you know, sporty but aerodynamic, whatever, it would have been much more successful. It had way too much glass, way too much weight.

RE: The glass added to the weight, of course.

GK: Oh, yeah, that was the heaviest part as far as one service goes.

RE: And Teague liked glass. I mean, that’s the reason why there was so much glass.

GK: At that time it looked pretty good. I don’t think anybody cared about weight so much. Especially on a big car—the 4,000 pound behemoth that Chrysler and GM were doing.

RE: Looking over your career I think it’s very interesting that you began with Packard which folded, and then ended with AMC both having succumbed to financial difficulties and both, of course, were tremendous innovators in engineering and design and they still both have legions of fans and car enthusiasts. What are your thoughts on almost book ending your career as an automotive designer working at Packard early on and then working at AMC? Do you have any sort of nostalgic type thoughts of what could have happened or what could have saved those companies?

GK: No. Everybody does a little Monday morning quarterbacking on, you know, both those companies why the result of their demise of both of them. The story I got about Packard was that Jim Nance, who was President at that time of Studebaker, Packard—he was looking forwarded to get a government contract for Studebaker trucks. Well, during that—his efforts, Charlie Wilson, your GM guy was appointed, I forget what his appointment was in Washington, but he had a lot of clout. And that contract that Nance was hoping for went to GM. So, we were left without any collateral and money to build them. And that’s unfortunate, but that, you know, that’s too bad.

BP: Not really. I remember Wilson was famous for saying what’s good for General Motors is good for the country. And I know that alarmed a lot of people who weren’t necessarily in agreement with that at all. Studebaker, Packard, Chrysler—those guys must have thought, oh, wait a minute.

GK: Yeah. That thinking, you know, you’re thinking that way locally, but they forgot that there’s a big country out there listening to this.

BP: Exactly.

BP: I wonder—you know I’d like to go back and ask you if you could own any car in the whole world it doesn’t matter European, American.

GK: Mercedes 540K.

BP: Okay. A Mercedes 540K, favorite car.

RE: What was your favorite car you ever owned?

GK: I did succumb to the desire to have, you know, a V8 with a hell of a lot of power. Although, I did own a Javelin for a while, and I did have a Plymouth Fury. I forget what year it was, a convertible, and that was a nice car. I had nice profile. I liked it so much with the roof up I rarely put it down.

BP: Yeah. The late ’50s cars and products, in general, were dashing and, I mean, I though they definitely were the style in leaders during Exner’s hay day in the late ’50s, no question about it. It scared GM to death, of course, but you know as it turned out I think Chrysler’s problem was in those years was quality control.

GK: True, true.

BP: And GM at that time at any rate had pretty good quality. So that people who bought a Chrysler car and had problems with it would often turn away from those kinds of problems and look for a car that was more reliable and so on.

GK: One of them was that torsion bar. After so many miles it didn’t know where—you could have a car parked in from of your house and—BOOM, they would give out.

BP: Yeah. That was a pretty nasty thing to happen.

GK: And everybody heard about that and conclude that I’m not going to buy that car.

BP: We heard stories about guys opening the door and the handle came off in their hand. I don’t know if that really happened but it may have just been a story.

GK: I wouldn’t be surprised if that happened.

BP: But, yeah, we heard that about Studebakers, too.

GK: That was on Newberg’s day. He and his wife owned a company, and Newberg was steering work to that company. So that was the end of Newberg when they finally decided, hey, what’s going on here? You know, this wasn’t fair to the company to have him do that.

BP: Yeah. Were there any particular foreign cars or foreign designers, well, you mention Mercedes 540K which of course would be a great classic, one of the great European classics, were there any other contemporary European cars or car designers that you particularly admired German, English, Italian, whatever? I’m just curious. Where were was your sort of design soul at the time? Who were your sort of design ideas at that time. I’m just kind of curious. Can you pull that out?

GK: Well, the Mercedes was very popular, and once you get that logo the Mercedes emblem on a car, right away you think quality. You know, if you took that emblem off and get that body and paint it in clay color, you would think it’s just a ho-hum car, you know. But that emblem sold a lot of cars. Of course, the engineering was actually superior to most cars at that time. In fact, at Studebaker they did a wheel cover with a three-prong star and they had to quit making it.

BP: They had to take it off, too. They got after them.

GK: Yeah. Did you hear about that, too?

BP: Oh, I sure did. Loewy, Raymond Loewy was their guy at that time, and I guess some of the guys who worked for him were for it.

GK: Yeah, Exner was a designer and Loewy was a promoter. He’d come in and shake hands with everybody and whatever and put a porthole in one vehicle and that was it. He didn’t do anything else. So the story goes.

BP: There’s probably a lot of truth in that.

GK: Yeah. Duncan McRae was the head of Studebaker at the time. Did you ever hear of Duncan McRae?

BP: I’ve heard his name, but I never met him.

GK: Oh, yeah. Very dashing figure, tall handsome guy.

RE: Where did he go after Packard finally closed up? Because he designed that Packard where he took the golden Hawk and made that really long sloping nose on it. I think that was a ’59 Packard Hawk. Really is sort of an unfortunate design.

GK: That is a horrible mistake trying to make a Packard out of a Studebaker, gees. It’s a shame almost sacrilegious to use the name Packard and put it on a Studebaker. You might as well put it on a kiddy car. I had been to South Bend on some occasions to see the progress, and I just hated it at that time. I didn’t care what they think. It was ridiculous and I didn’t want any part of it.

RE: Now, George, pick your favorite car that you actually had a significant design influence on and which you think you’re still very proud of?

GK: I had a Javelin for a while and that styling-wise that had to be my favorite design. I liked that.

RE: Yeah. It’s a beautiful car. Bill, do you have any other follow-up questions that you would like to ask?

BP: I wonder if you knew Tom Hale, as a young designer?

GK: He worked at American Motors for a while.

BP: Yeah, he did. He worked with me in the studio at GM.

GK: Oh, really.

BP Then went over to American Motors. I guess he just couldn’t stand me. I’m just kidding. He had his reasons for leaving, but he left.

GK: Oh, he was hard to get a long with.

BP: He was a bit of a temperamental guy. Later he became an illustrator and has been quite successful.

GK: There was one time at lunch hour he was doing barn paintings. Everybody’s painting barns. and of course he developed into doing these beautiful paintings. Of course, he developed in doing these fantastic car pictures or whatever, and he was asking for like 18 to 20 thousand dollars for each painting, but it would take him months to do it. If you’re familiar with his work, you would see how much work there was in it. Where you get a chrome headlamp from an old car Then you get the sky in there and the trees the green of the trees, whatever, all the reflections in there. Just amazing work.

BP: Did you work with any of the guys who worked at Studebaker or work for Loewy in Studebaker?

GK: Like Bill Bonner was there.

BP: Bill Bonner. Okay.

GK: Yeah. And there’s Duncan McRae was the Director of Design at Studebaker/Packard.

BP: I want to make note of that. I want to know more about Duncan McRae. I don’t know much about him.

RE: Did Duncan McRae go on after Packard? Did he retire at the end of Packard’s days?

GK: I don’t know how long he stayed there. I really don’t know. I don’t know when he retired or whether they just gave up, whatever, but quite a character?

BP: When did you actually retire from AMC?

GK: 87. I was 62, and Francois Castaing was the Renault hot shot at that time. Evidently, word got down probably through Chrysler that they were trying to terminate anyone that was and older. And I had been getting good appraisals. Finally, I get one that’s, you know, mediocre. And if I don’t improve, they’re going to fire me. What the hell.

BP: You know, they staged some of those appraisals. That happened at GM, too. Yeah. And in one case at least GM got a lawsuit slapped on them that cost a couple of million dollars.

GK: Well, he didn’t want to fire me. They just wanted to make me so miserable they took the Jeep studio away from me and gave it to an interior guy. And they said, “Here you can have a little studio.” It was two guys who were rejects from other studios. In other words, they weren’t that well know and their talents weren’t that great. And we putzed around with various little things, insignificant stuff.

So, finally, I think after a few months, they changed my appraisals to something passing, and I used to get good appraisals up until that time. Anyway, I guess I was ready to have a nervous breakdown everything was so screwed up. After they took the Jeep studio away from me, they were calling me all the time from different departments wondering what’s going on, what do we do? Do you approve this and that? And I said, “Go ask Francois Castaing he’s a jerk.” But I couldn’t do that very often, you know, I still had to answer to him.

BP: I understand the strategies Yeah, yeah. I retired from GM in 1996. And by that time they were pulling all of those kinds of routines. Had it not been true, you know, GM stayed a viable place to work for a long time when there were other problems in other companies were very evident, but eventually it caught up with GM, eventually.

GK: Yeah. I almost took a job there.

RE: What year would that have been?

GK: It was after Packard folded, and I’m trying to think of one of the personnel names, they invited me over and we and I remember we had lunch. It was beautiful.

BP: Was that when GM had the tech center done. That was around ’55, ’56, right in there. So, it was probably in the late ’50s about when the time that you went to Chrysler.

GK: Could be. But it was a nice building. They wanted me to start in the beginner’s studio in advance there. I don’t know what they called it.

BP: Design development.

GK Oh, okay. And I thought, you know, I was just a manager of a studio. Do I want to start this way? And like a dummy, I should have taken the job. But, anyway, I made a lot of mistakes during my career and that was another one.

BP: Didn’t we all.

RE: Well, you’ve done a lot of beautiful work as evidenced by the drawings during the sale.

GK: Good.

Re: Well, I thank you very much, George, I appreciate your time and your contribution towards the archives.

GK: You’re welcome. Glad to talk to you both.

Very interesting, enjoyed reading and listing to him. Interesting piece of history,

I worked at AMC from 1977 to 1985. I worked on the SJ, a replacement for the Grand Cherokee. Roy Lunn, VP of Engineering made the decision in early 1978, that AMC would not be the first company to do an all plastic exterior surface car, and the vehicle was not the right size. Del DeRees had a great deal to do with the packaging of the new Cherokee, which grew longer & shorter wheelbase several times, until Dale Dawkins, Director of Sales & Marketing(?) picked the short version. This resulted in the shortest rear door entry ever done on a 4 door.

AMC baked the design of the Cherokee, then went on 2 trips to the Wind tunnel at the U of Maryland, where things were massaged. A later trip to U of M, confirmed the final design Cd numbers.

We all worked together pretty well, union and not, because there wasn’t the time or energy to waste playing games. The best part of working at AMC was the freedom to do your job without the micro-managing typical at the Big 3. You know your job, so do it. Screw up, and you were in big trouble. This was why AMC could design and build cars with less than 1500 people on Plymouth road, just a few more than GM had in styling! Personal responsibility was rule, so everyone kicked butt to get things done.

The platform teams were introduced by Gastaing, resulting in the same number of people now working 20 hours more a week, to get the same amount of work done. It was not a plus at AMC, like it became at Chrysler in 1988, after Gastaing took over there.

Great interview! I’m late to find this, but was wondering if Mr. Kripinsky recalls working on the Marbon Chemical CRV project when he was at William M. Schmidt Associates? It was a Cycolac-bodied sports car with a two-piece thermoformed body. It should have been there in the mid-1960s. If not, any idea who was behind the design? I have seen the design credited to both Schmidt and the team at Centaur Engineering, who built the chassis.

Thanks,

Harold Pace

My career didn’t cross paths with George until arriving at AMC. We were the same level, there, and it was a delight to learn he was a fellow alum from the Cleveland Institute of Art. We were the only two at AMC from that school.

George, I quickly learned, was highly talented and doggone smart. He was also borderline crazy which meant he fit in well with the rest of the design staff. We got along great and I valued his friendship. He could be one of the most hilarious designers anyone would want to know.

At the time of the Chrysler takeover they treated George just as he states and there was nothing the rest of us could do about it.

My luck with Castaing was different, perhaps because of a modest ability with the French language. When he’d come into my studios we would discuss business in his native language.

Sad to read in today’s paper that George Krispinsky died on April 16, 2020 – he was 96. https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/freep/obituary.aspx?n=george-krispinsky&pid=195997753