Part I: Predecessors to the Falcon

By Jim and Cheryl Farrell

Conventional wisdom has it that the 1960 Ford Falcon, a basic, no-nonsense compact car, was created by Ford vice president Robert McNamara who dictated its conservative, almost “granny-looking” design and mechanics. During its first year on sale, McNamara’s homely compact car outsold competitive compacts from GM and Chrysler. All that is true, but there’s much more to the story.

It’s not well known, but the Ford Falcon was preceded by 30-years of attempts to develop a car smaller than what Ford was already producing. Ford Motor Co’s attempts to develop a smaller Ford actually began in the mid-1930s, when Henry Ford himself encouraged development of a rear-engined small Ford. A few years later, Henry’s ideas resulted in the smaller but not very practical 1941 Plastic Ford. World War II stopped most car development, and by war’s end because of Henry’s advancing age, his involvement in any development disappeared as did his plastic car proposal.

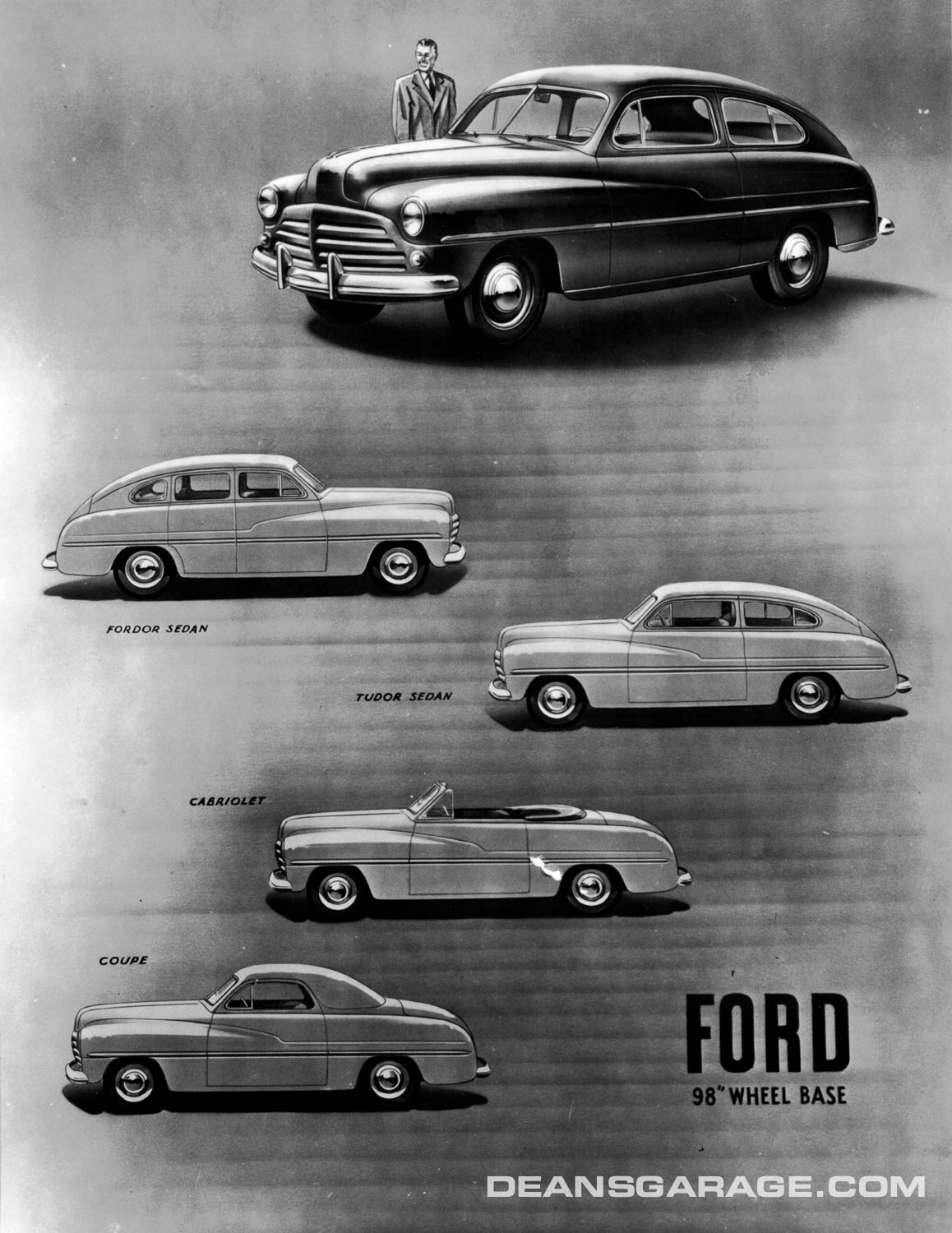

Just prior to the war, Edsel Ford and Bob Gregorie (Edsel’s design chief), recognizing that Ford products had been gradually getting bigger and more expensive, included a smaller Ford in their postwar plans. The idea was that the smaller Ford, which was eventually called the “Light Ford” should be designed to look as much as possible like the larger full-sized Ford.

Edsel died in April 1943, and Gregorie left three years later. Although Edsel’s death was unexpected, as was Gregorie’s departure, it accelerated open warfare among those executives who were not fired or did not leave under pressure. In those crazy times, long-time Ford metallurgical engineer Hudson McCarroll became Ford’s chief engineer. McCarroll made producing the Light Ford his signature project.

After Gregorie left, design work at Ford was largely managed by his successor Tom Hibbard, but most of the design work on the Light Ford was actually done by designer Bill Schmidt. Except for the grille, the design of the Light Ford looked similar to the larger Ford, which at that time was supposed to be what later became the Mercury. The Light Ford started with a 98-inch wheelbase, grew to 106-inches and was finally stretched to 108-inches. After design of the Light Ford was completed and its engineering was pretty well done, Light Ford test cars were on the roads in and around Dearborn. In April 1946, a new Light Ford Division was formed to produce the car. Tooling was almost complete when Ford executives began to have second thoughts about their plans to market a smaller Ford. Ford’s sales manager Jack Davis determined that because of the postwar sellers’ market, there was no need for a Light Ford then or at anytime in the immediate future. According to Davis, Ford could expect to sell every car it produced without the Light Ford. On top of that, Engineering determined the Light Ford would cost only 17% less to build than the “big” Ford.

In mid-1946 one of the executives hired by Ford’s new president, Henry Ford II, was Ernie Breech, a veteran of the automobile business. Breech became Ford’s executive vice president and Henry Ford II’s mentor. Because he didn’t think it would make money, Breech sold the Light Ford to Ford of France, where it was produced as the Vedette. Breech also proposed that the full-sized Ford become the new Mercury, and he and Ford’s new chief engineer, Harold Youngren, recommended a crash program to design a new Ford, but that’s a different story.

In 1947 Breech hired a former Fisher Body (GM) treasurer and controller named Lewis D. Crusoe to help reorganize Ford’s finances. Crusoe had retired from GM early, and was an expert in automobile production as well as automobile finance. Crusoe was so talented that by 1955 he had made himself the third most powerful man at Ford. Crusoe spent a lot of time at the Styling Center, and was well respected by designers.

In 1955, to take some of the burden off Breech who was approaching retirement age, he was promoted to chairman of Ford’s board of directors. At the same time, Crusoe was elevated from the head of Ford Division to a new position as vice president in charge of all vehicle production at Ford. Whiz kid Robert McNamara replaced Crusoe as head of Ford Division. Almost immediately after he was promoted, Crusoe and his then protege, another talented whiz kid named Jack Reith, recommended that Ford produce the Edsel, which turned out to be a disastrous overreach. One of the recommendations accompanying the Edsel proposal was that Reith become head of an expanded Mercury Division. McNamara was one of the few Ford executives who opposed the Edsel project and all of its sub-parts.

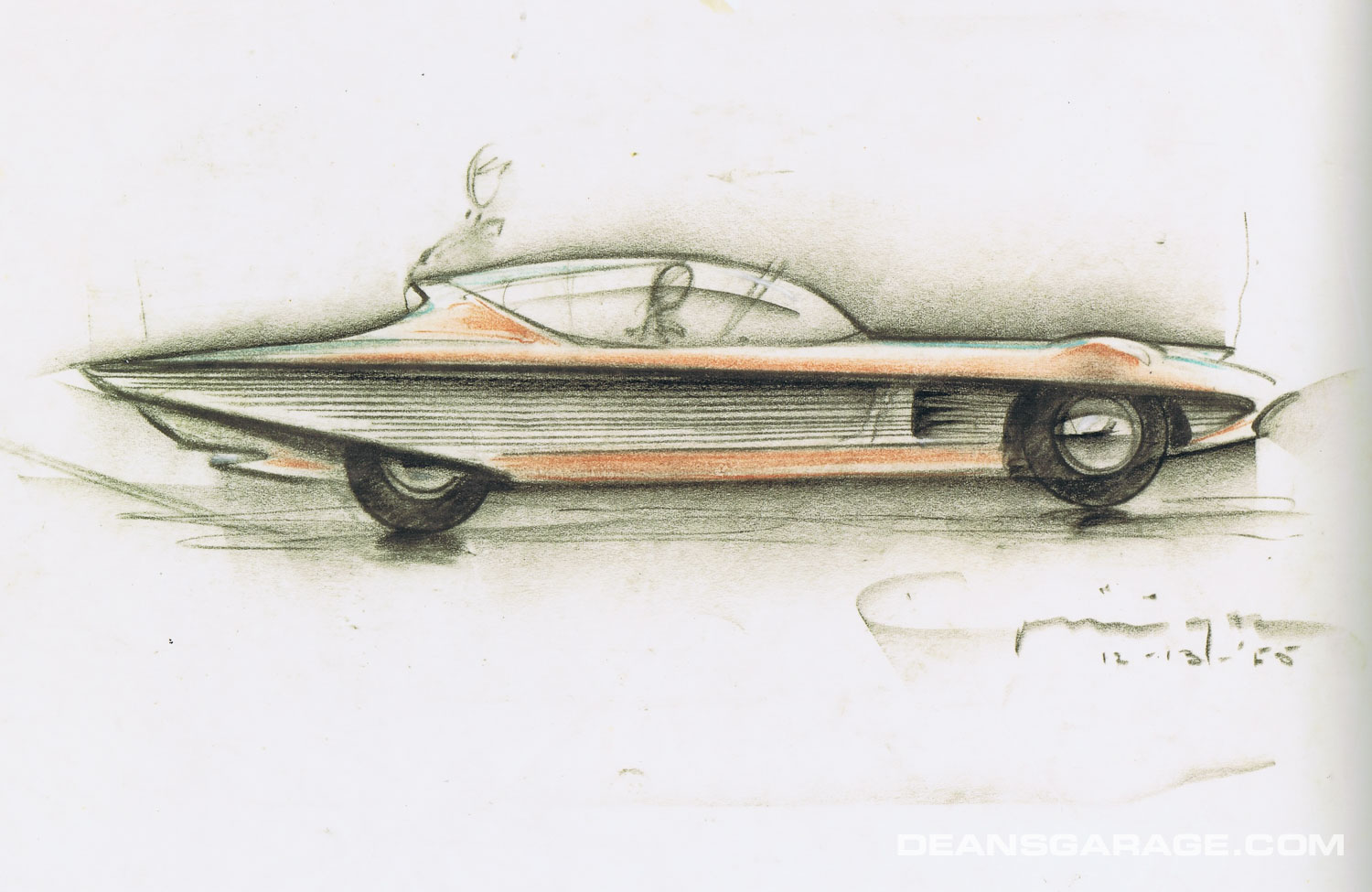

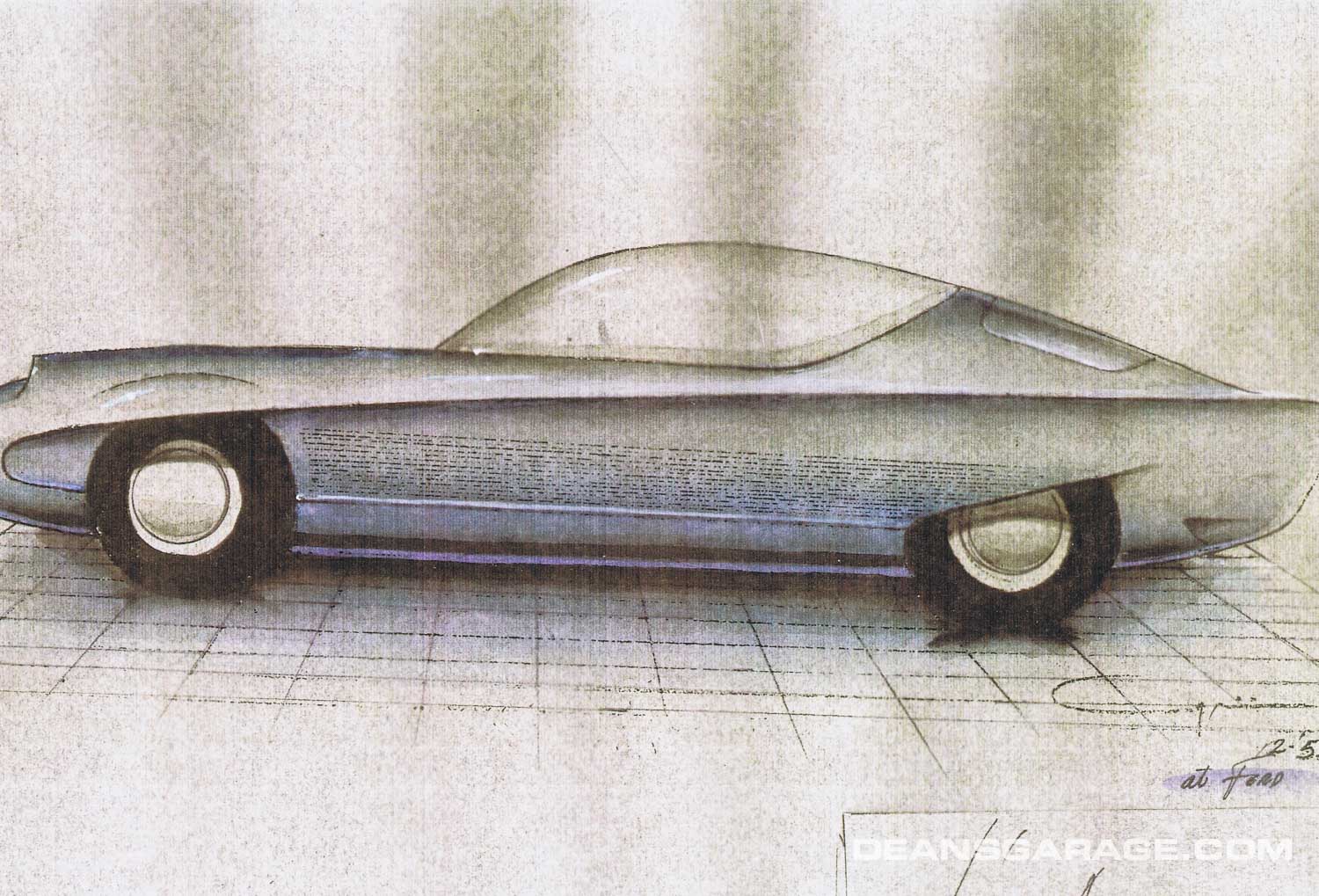

By the mid-1950s Fords (and Mercurys) were still growing in size just as smaller foreign cars were selling in greater numbers in the U.S. market. As a partial answer to the foreign car problem, Crusoe recommended that Reith’s Mercury Division (not McNamara’s Ford Division) produce Ford’s first compact car. Crusoe was impressed with the design work of recently hired designer Buzz Grisinger, who had just designed the continental kit for the ’56 Thunderbird. Crusoe recommended that Grisinger be assigned to Bob Maquire’s Advance studio, where the Stylerama cars were then being designed. Grisinger sole job was to design Crusoe and Reith’s Mercury compact. Although Grisinger micromanaged every aspect of the design, he was assisted at various times by designers Herb Tod, Bob Marcks, Bob Chieda and Ed Westcott. (At the same time, Mercury Division was also developing a “super” Mercury that was meant to share many of its mechanical parts with Lincoln.)

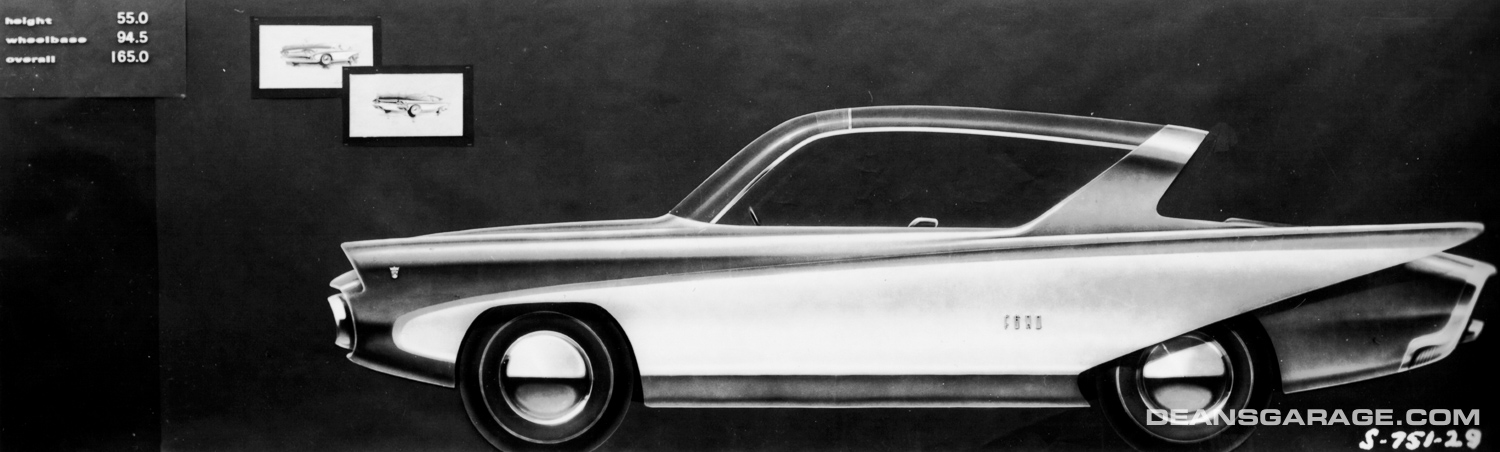

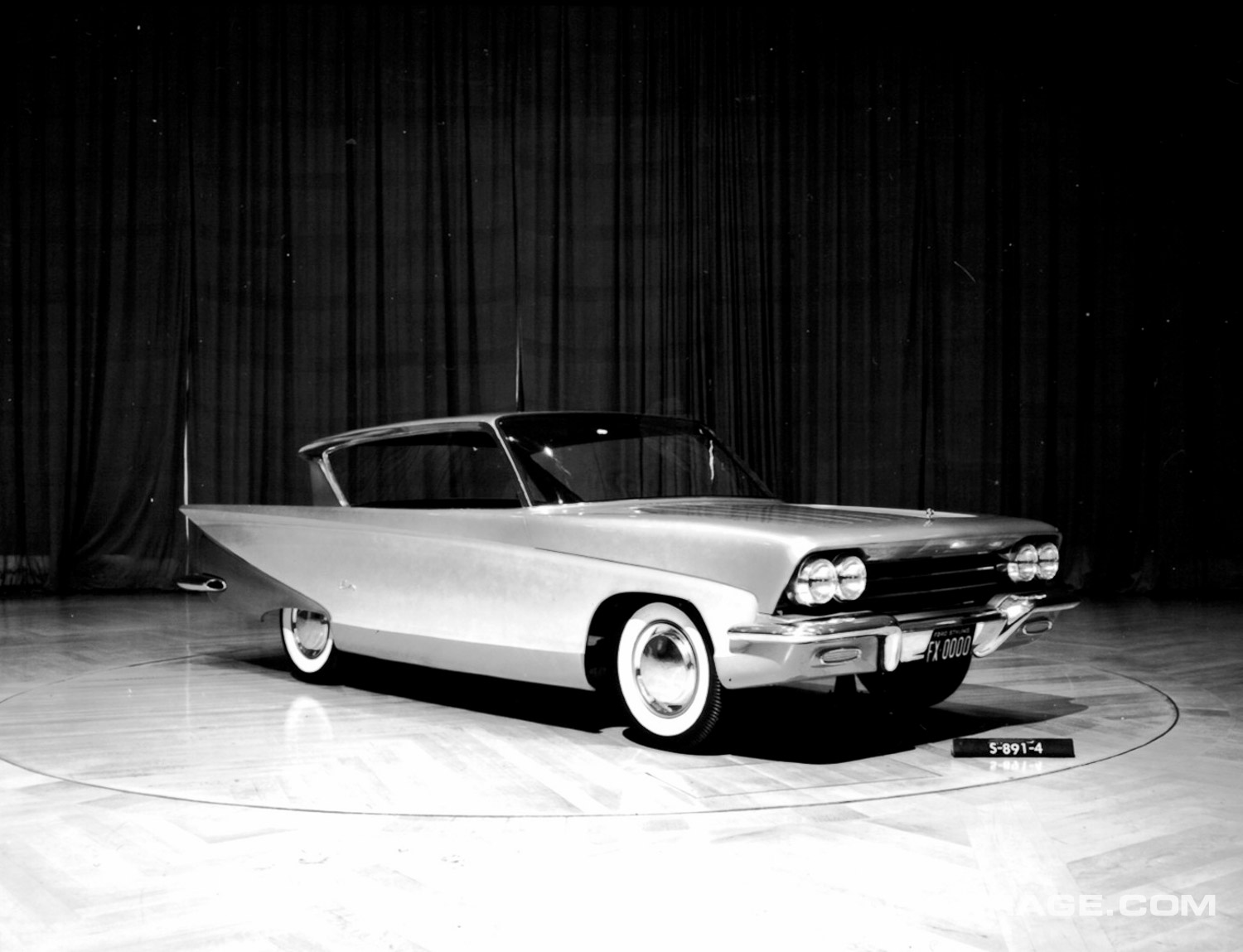

Grisinger started by presenting several proposals. George Walker had become head of the separate Ford Styling Center in May 1955, and he and Crusoe chose the final design. Walker wanted a modern space-age design for the smaller Mercury which was encouraged and approved by Crusoe. Grisnger got to work immediately, and six months later the smaller Mercury Grisinger named the L’Avion was finished as a full-sized fiberglass model with no interior.

No engineering accompanied the design work on the L’Avion even though Crusoe said he planned to produce the car for the U.S. market starting in 1958. Crusoe was usually ahead of the curve on automotive matters, and Grisinger strongly suspected or may have been told that Crusoe planned to mate the L’Avion’s American body to a European frame and running gear.

Nothing went as Crusoe and Reith planned. Even before the ‘58 Edsel was introduced, it, Mercury Division, Crusoe and Reith were in trouble. They were under attack from McNamara, Breech and others. Ford Motor Co. was and is a family controlled business, and Crusoe had overreached by engineering the replacement of Benson Ford by Reith as head of Mercury, followed by the termination of Bill Ford’s Continental Division. Everything caught up with Crusoe in October 1956, when he had a major heart attack. He was in the hospital or recuperating at home until May 1957, when he was retired, probably against his will. After Crusoe’s heart attack, McNamara assumed Crusoe’s duties until the following May when he got Crusoe’s job. In October 1957, because the ’57 Mercury was not selling as well as Reith had forecast, Reith was also forced out.

Photos: Ford Design

Books by Jim and Cheryl Farrell

Ford Design Department—

Concepts & Showcars

1999, 10×13, 400 pages, Fully indexed

900 photos. Includes 150+ designers and sculptors, and highlights 100 concept cars.

ISBN 0-9672428-0-0

Lincoln Design Heritage:

Zephyr to LS (1936-2000)

2021, 10×13, 480 Pages, Fully Indexed

1,600 photos and illustrations

ISBN 978-0-9672428-1-1

The Ford book is $50 plus $7 S&H (US). The Lincoln book is $85 plus $10 S&H (US). Both books bought together are $110 plus $17 S&H (US). To order, email: cfarrell57@gmail.com

This is a fascinating analysis of why, except for the Ford Division with its standard wheelbase Custom-300 series Ford and the longer wheelbase Fairlane-Fairlane 500 series, everything else fell apart for Ford in the fall of 1956. i once read that Reith had worked for Ford France and had influenced the production of the V-8 60-engined Simca Vedette.

The Ford machinations are similar to the arguments at Chevrolet over Earle S. MacPherson’s development of the small Chevrolet Cadet, which was nixed for production several times, most likely for the same reasons H.F.II, Ernie Breech and Lewis Crusoe nixed the small Ford idea due to the post-war market.

Why H.F. II allowed Breech and Crusoe to remove his younger brothers from corporate involvement beyond the family stock holdings is a mystery to me. For a company like Ford, ultimately it was and is career-ending for Breech and Crusoe. Just ask Lee Iacocca and Jac Nasser ! G.M. envy is what drove Ford to adopt the Reith five divisions proposal that seriously backfired. But even though the Edsel debacle cost Ford a reported $ 250-million, the unintended consequence was the Ford had the production capacity to produce over 410-thousand Falcons, in addition to the regular Fords, the long wheelbase Mercurys, the huge tunit-bodied Lincolns and Thunderbirds and all of the variations of Ford trucks for the 1960 model year.

I know styling is largely a matter of taste, but I found the Falcons from the no-frills 1960 to the evolved 1969 model to be one of the most enduring designs, while the Edsel/Mercury Comets from April, 1960 to be oddly styled, even though it sold well until it evolved and stretched into an intermediate after the demise of the Meteor.

The Comet became a step child even before it emerged from its basinet. A stand-alone make until it was adopted by Mercury in 1962, it was a foster child in the Falcon family. When the Comet name lost its appeal it was adopted by the mid-size Fairlane-Torino family and renamed Montego, then demoted back down to the Maverick stable, which had quietly replaced the Falcon. Just one more chapter in the dysfunctional Lincoln-Mercury Roller-Coaster Family of Fine Cars.

I hope Mr. and Mrs. Farrell write a book on Ford Design Heritage from 1949 through 2000. The Lincoln book was brilliant.

For as much as McNamara seemed to be disliked among those who worked below him, his 1960 Falcon, with its simple, cheap, and almost crude chassis design, was in production in variations of its basic form under vehicles such as the Maverick, Mustang, and Granada/Monarch through the 1980 model year. In those 20 years it made Ford billions in profits.