Design of the 1963 “Full-Sized” Ford

By Jim and Cheryl Farrell

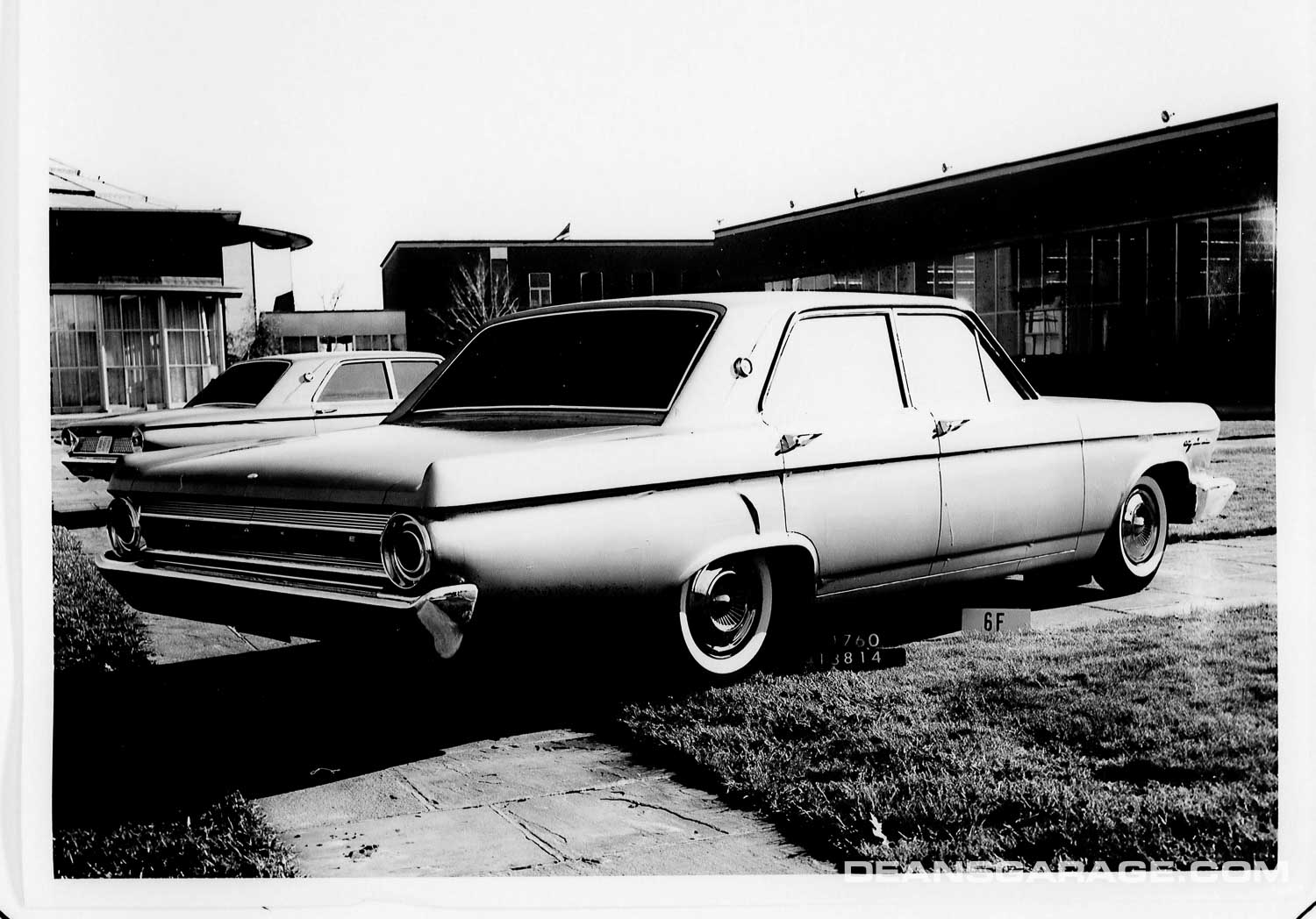

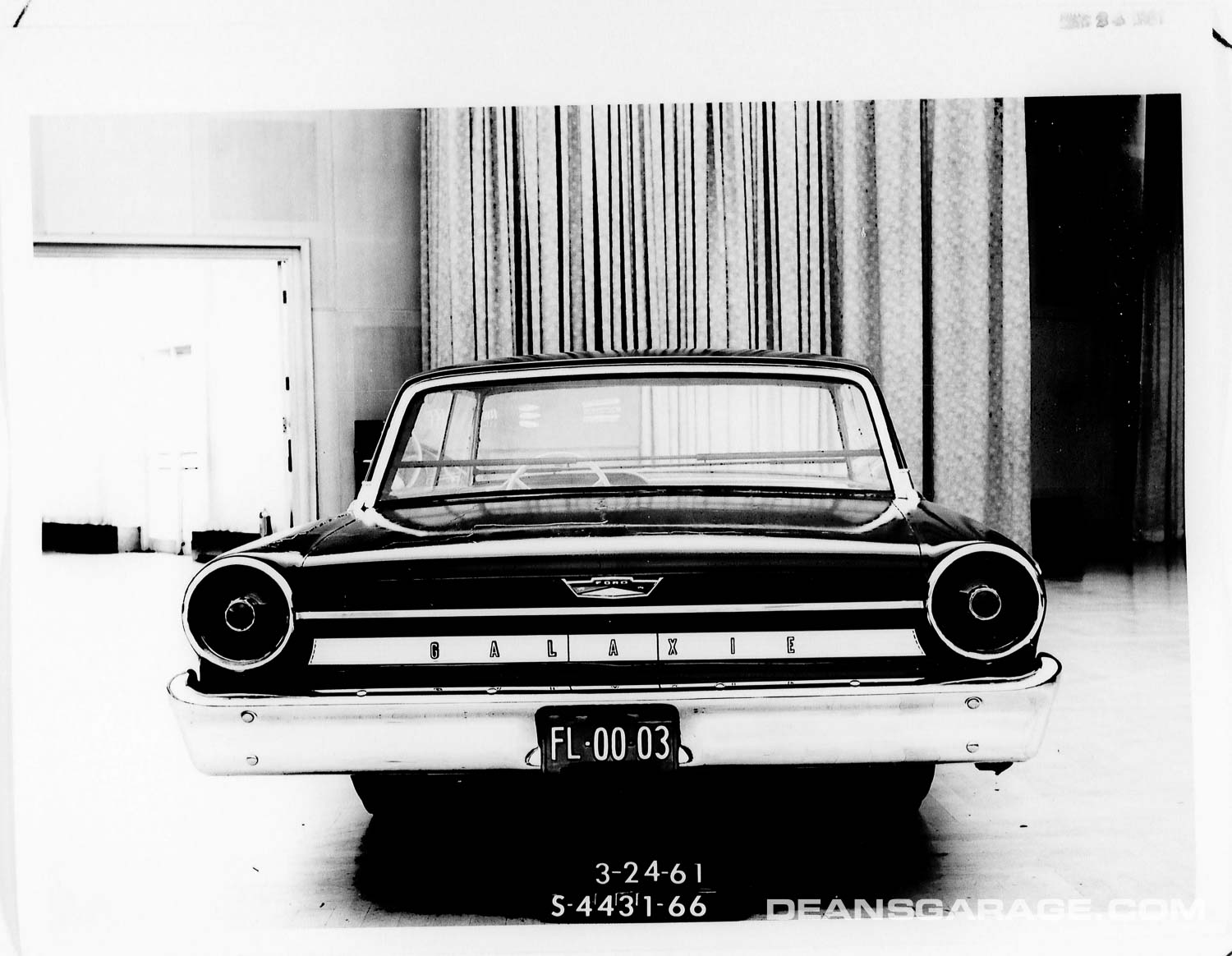

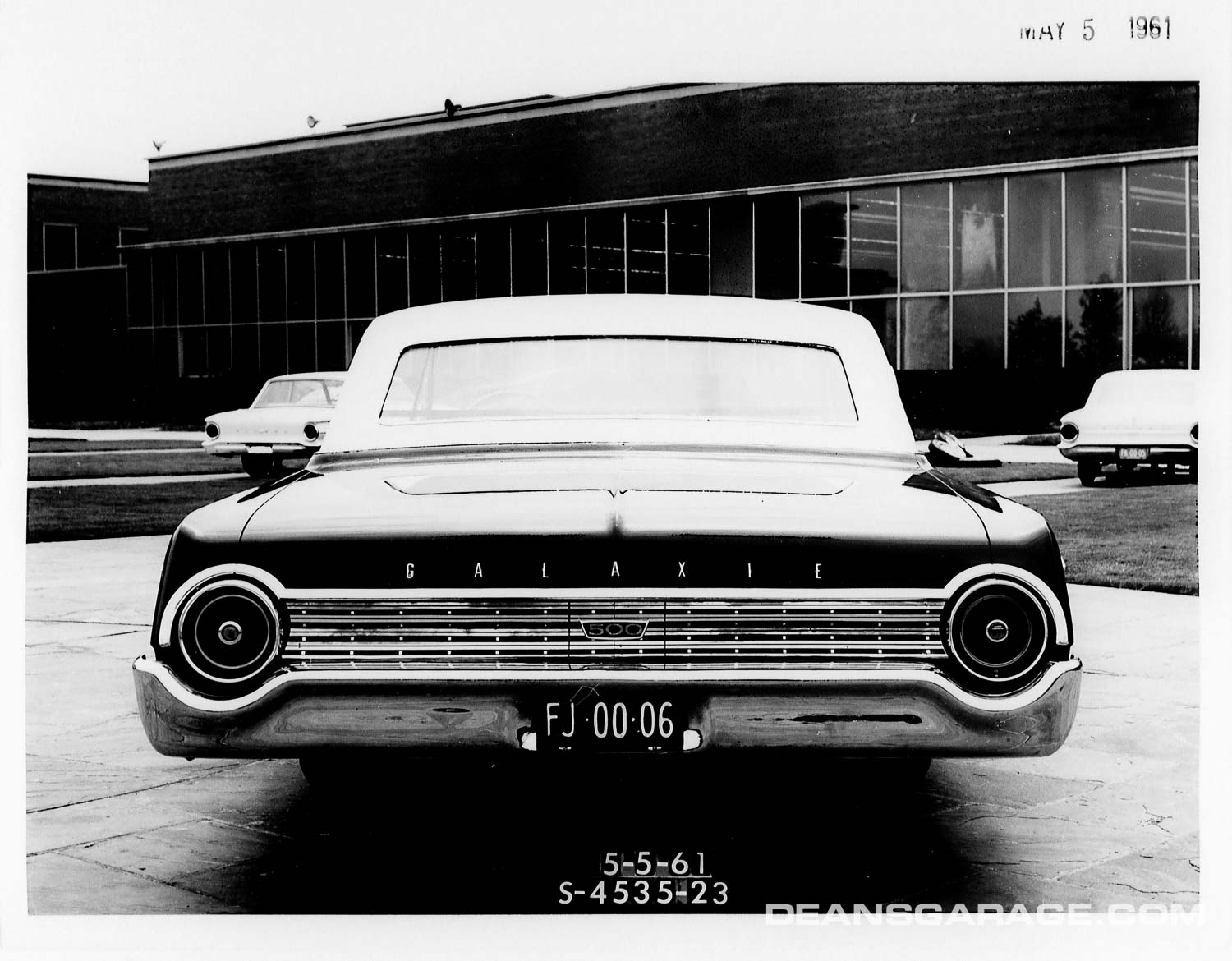

Most of us when we hear the words “1963 Ford Galaxie,” imagine an R-code 427 fastback on a NASCAR track going like hell. As great as the full-sized ’63 Fords were, we need to recognize they shared the same bodies with 1960–64 models. That meant that each year, Joe Oros, the Ford studio design chief, had to come up with ways to change the looks of the full-sized Fords so they appeared new and fresh, while still showing continuity with past years’ Fords.

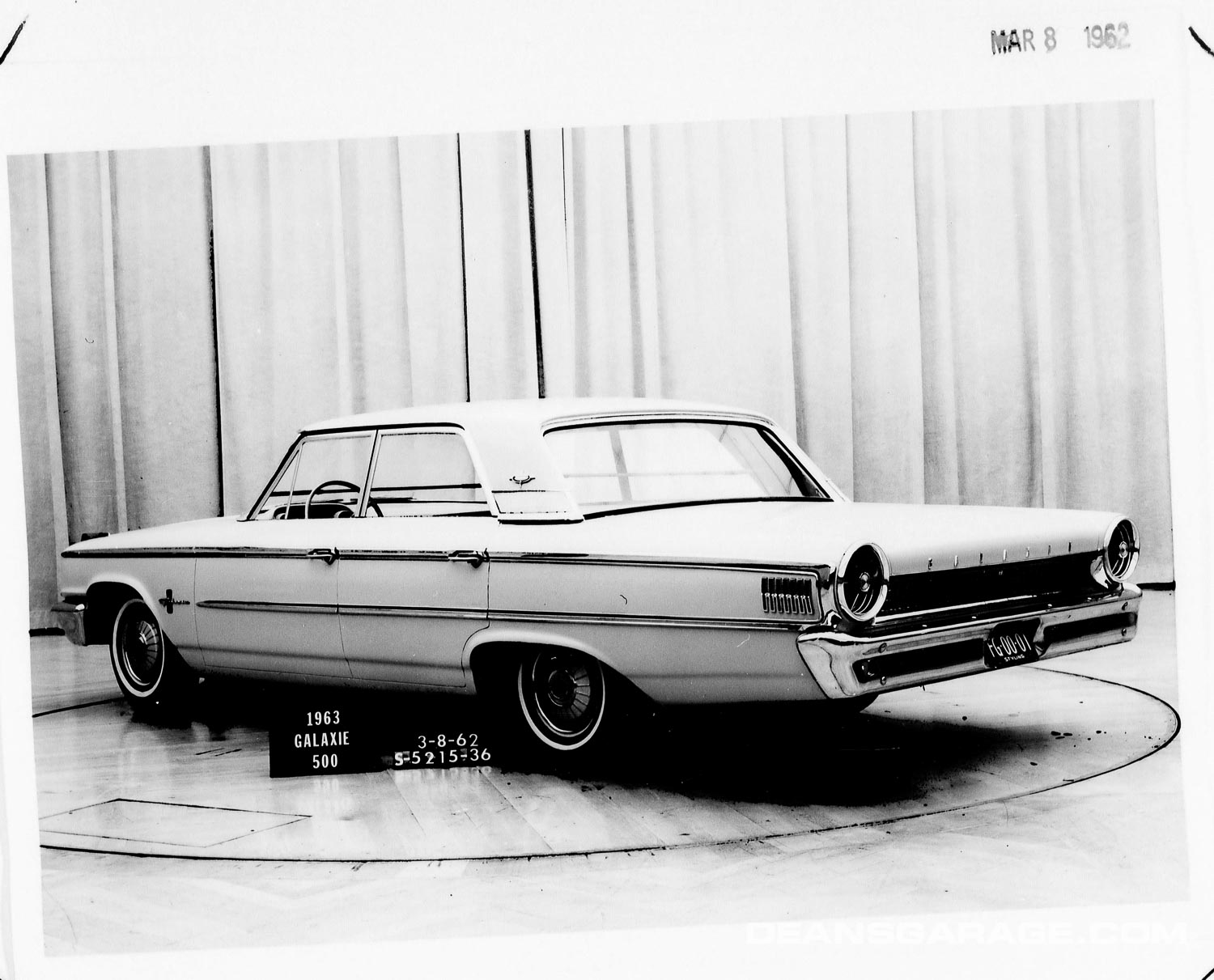

The ’63 big Ford’s design is arguably the most aggressive looking of the bunch. The design also looks more unified and less like it came from different designers who designed different parts. Nor does it look like it was designed by committee. It looks aggressive because it was designed that way, and the design was unified looking because it was designed by a single designer.

First an explanation how Ford products were designed. At the time the ’63 full-sized Ford was designed, (excluding the interior studios) Ford’s Design Center had separate exterior studios for Fords, a combined Lincoln and Mercury studio, an Advanced studio, a Corporate Advanced studio, and a Truck studio. The Ford studio also had smaller studios within it for the different Fords, all under Joe Oros. Individual designers were transferred from one studio to another approximately every six months, so they would remain “fresh,” but often talent or a working relationship in a particular studio meant a longer time spent in a particular studio before being transferred.

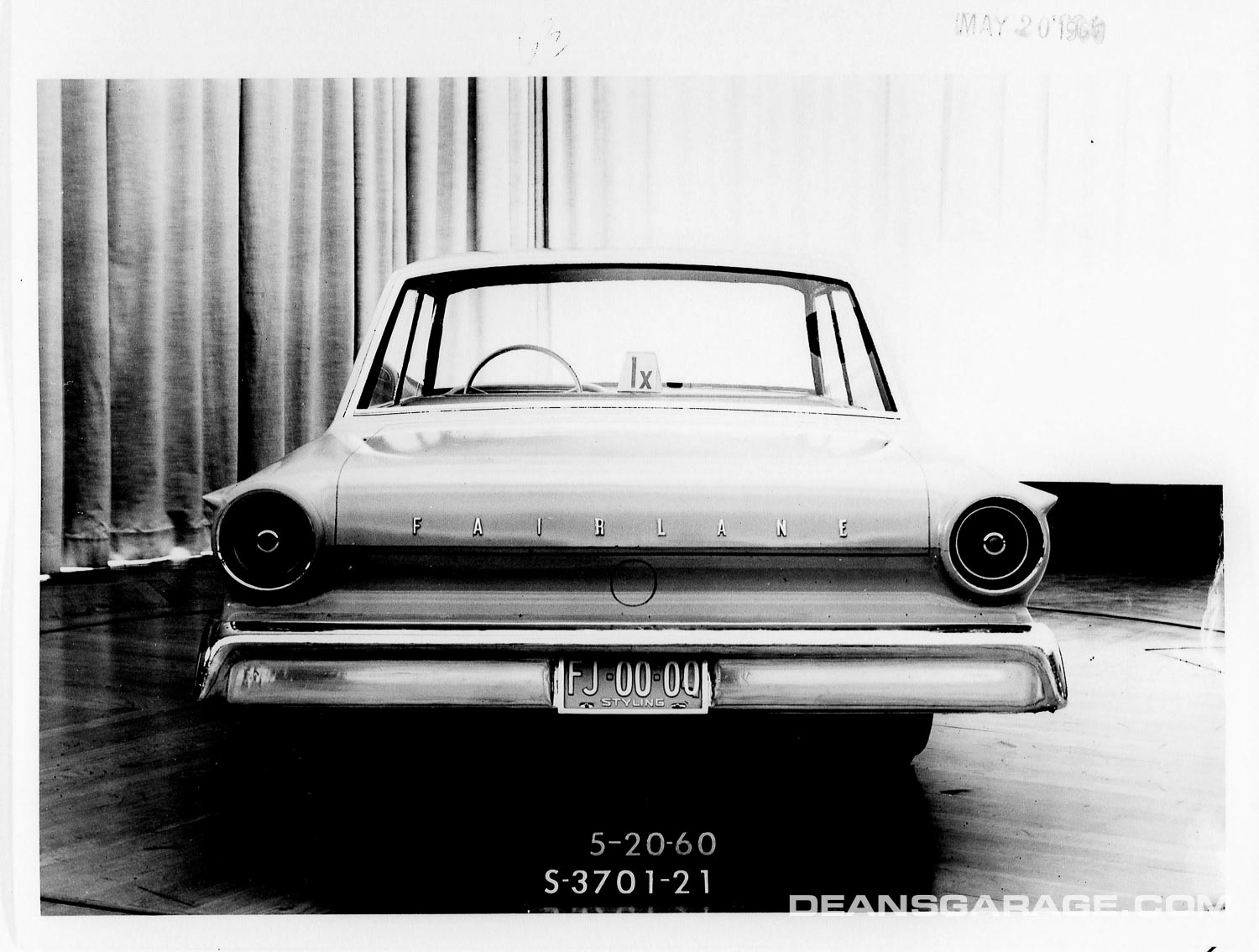

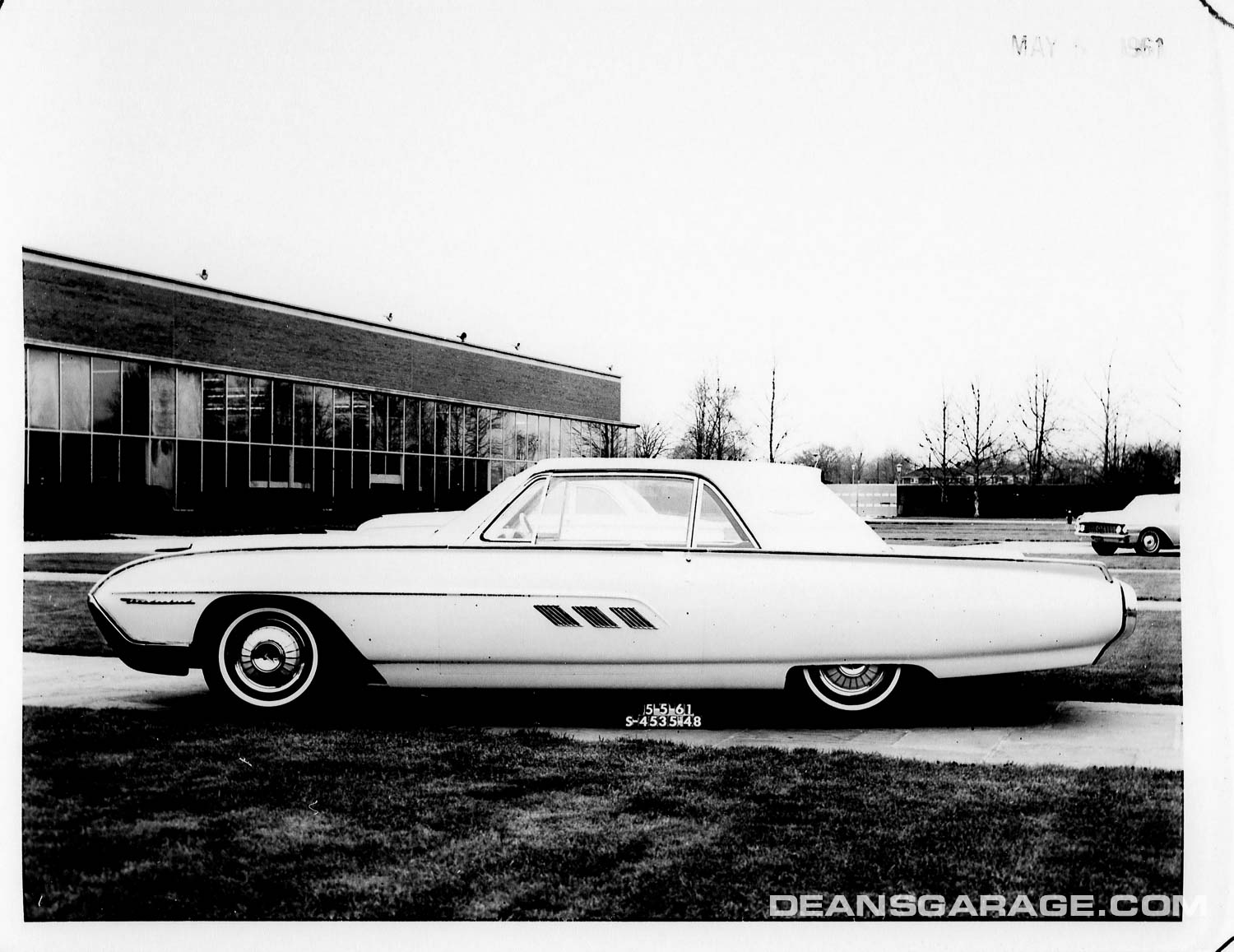

Oros was responsible for the design of the Falcon, a new medium-sized car that debuted in 1963 called the Fairlane, and the Thunderbird, as well as the full-sized Ford. Falcons and Fairlanes had or soon would have their own sub-studios, which sometimes included more than one model. Ford trucks, including commercial trucks, were designed in a separate Ford studio run by Bill Wagner, but supervised by Oros.

From 1956 to 1968, Oros was head of the Ford Design studio. In 1968, he was promoted to become head of design, Ford of Europe. Oros’ family was from Romania, and he didn’t speak English until he started grade school. As an adult, Oros always spoke with a slight accent, and his wording was sometimes a little different or stilted. He was a high achiever who graduated from Cleveland Institute of Arts with the highest grades in his class. After attending GM’s design school, where he met life-long friend Elwood Engel, he took a job with George Walker’s private design firm. Oros wanted to be an industrial designer and preferred NOT to design cars, but he proved to be too good at car design, and his talent eventually forced him into that field exclusively. As a Walker employee at Ford, Oros started with a small model designed by Richard Caleal that he and Engel redesigned into Walker’s winning 1949 Ford proposal. Oros was also the primary designer of the ’52 Ford, the ’57 Ford Fairlane, the X-100, and the Quicksilver which became the ’60 Ford. Ford forbade designers from taking sketches or photos from the Design Center building. Oros was luckily the only designer who followed that rule.

Oros worked so many hours that his wife encouraged him to buy a boat, but without a radio phone so he would have to spend at least one day per weekend with his family out on the water—and unavailable to anyone at work. Most designers recognized Oros’ talent, but he was not the most popular person at the Design Center. He was so focused, he appeared to have no sense of humor (or kept it hidden). Designers (especially younger ones) sometimes made fun of him behind his back because he walked fast with his arms thrown out in front of him, often without seeing other people who were in close proximity. Oros was generous to a fault, and often helped refugees, especially those from Romania, find jobs at Ford. After he retired to California he missed working, so he designed and supervised the building of a Romanian Orthodox Church.

Even though there were no management changes in the Ford design studio, there were monumental changes at the Styling Center that effected design in general. In mid-1961 Gene Bordinat succeeded Walker as a Ford vice president and general manager of the renamed Design Center. That change was not without difficulty, and it resulted in bad feelings from Walker towards Bordinat and Ford executives together with a false expectation Walker gave to Oros that he was the next general manager of the Styling Center.

After Bill Ford engineered Bordinat’s surprise appointment as general manager, a bitter Walker encouraged Engel and Oros to both leave Ford. Walker got Oros an interview at American Motors, and he considered becoming their head of design, but Bordinat helped him decide he still had a future at Ford, so he stayed. In November 1961 Engel who had been Walker’s assistant manager, and under Bordinat, remained a studio head but not assistant manager, took a job as head of Chrysler design. The job was arranged by Walker. Walker also undermined Bordinat to the point Henry Ford II asked him to leave Ford. After that, it took some months for Bordinat to solidify his control at the Design Center, but that quickly happened.

Designers in the Ford Production studio in 1961, where Oros kept his office, included Damon Woods (exec), Bill Boyer, George Barbaz, Fred Cole, Frank Huff, Ken Pheasant, Jim Kowsky and John Huff; the Ford Station Wagon studio, which included designers Jim Darden, Dick Kessler, Stan Piekny, Rod Smith, Jack Telnack and Tony Walley; the Thunderbird and Falcon studio included Bud Kaufman (exec), John Foster, Marty Kallman, Daryl Larson, Ken Nelson, Bill Shannon, George Schumaker and Mac Thompson; and the Ford Preproduction studio, located downstairs, which included Gil Spear (exec), George Golbics, Allen Irwin, Rod Lloyd, Bob Marcks, Jack Mills, Charlie Phaneuf, Jim Powers and Bob Winterhalter.

There was also a changes at Ford Division that had some effect on design. Although Ford’s Product Planning Committee chose the designs produced, the head of Ford Division, depending on who it was, influenced design to a greater or lesser degree. Jim Wright had been head of Ford Division since 1957. When Robert McNamara became president of Ford in November 1960, Wright was replaced by Lee Iacocca. Wright, although one of the whiz kids, was never a car guy, but Iacocca was. Over the next several years, Iacocca’s influence on design increased. Iacocca was not only savvy about Ford’s racing and the optional engines that trickled down into production cars, he appreciated and insisted on good design. Designers as a general rule liked Iacocca and thought he had good design sense, although some found his language offensive. Iacocca kept in constant contact with Ford dealers throughout the country and was able to pass on to design mangers the features they wanted in new Ford products.

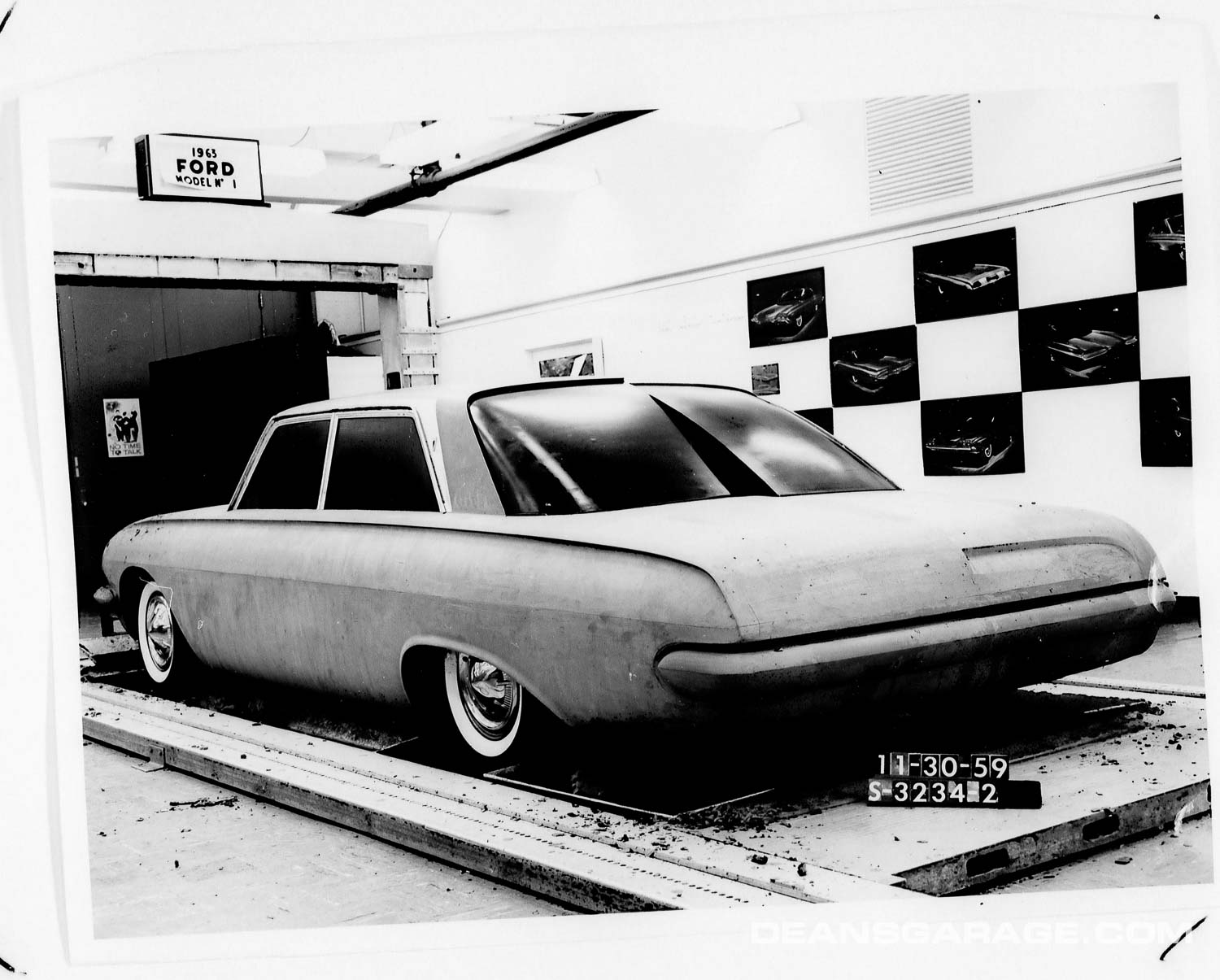

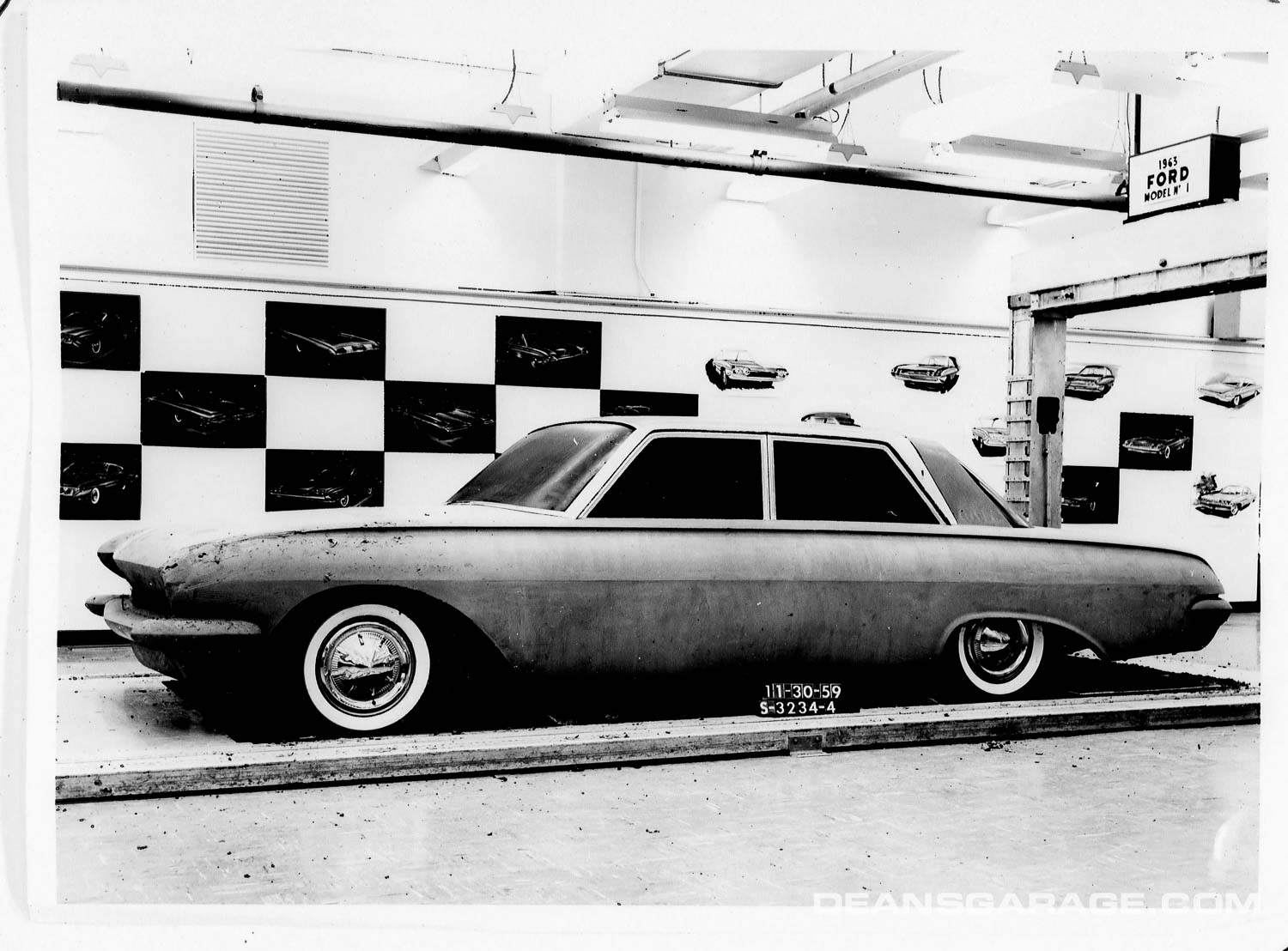

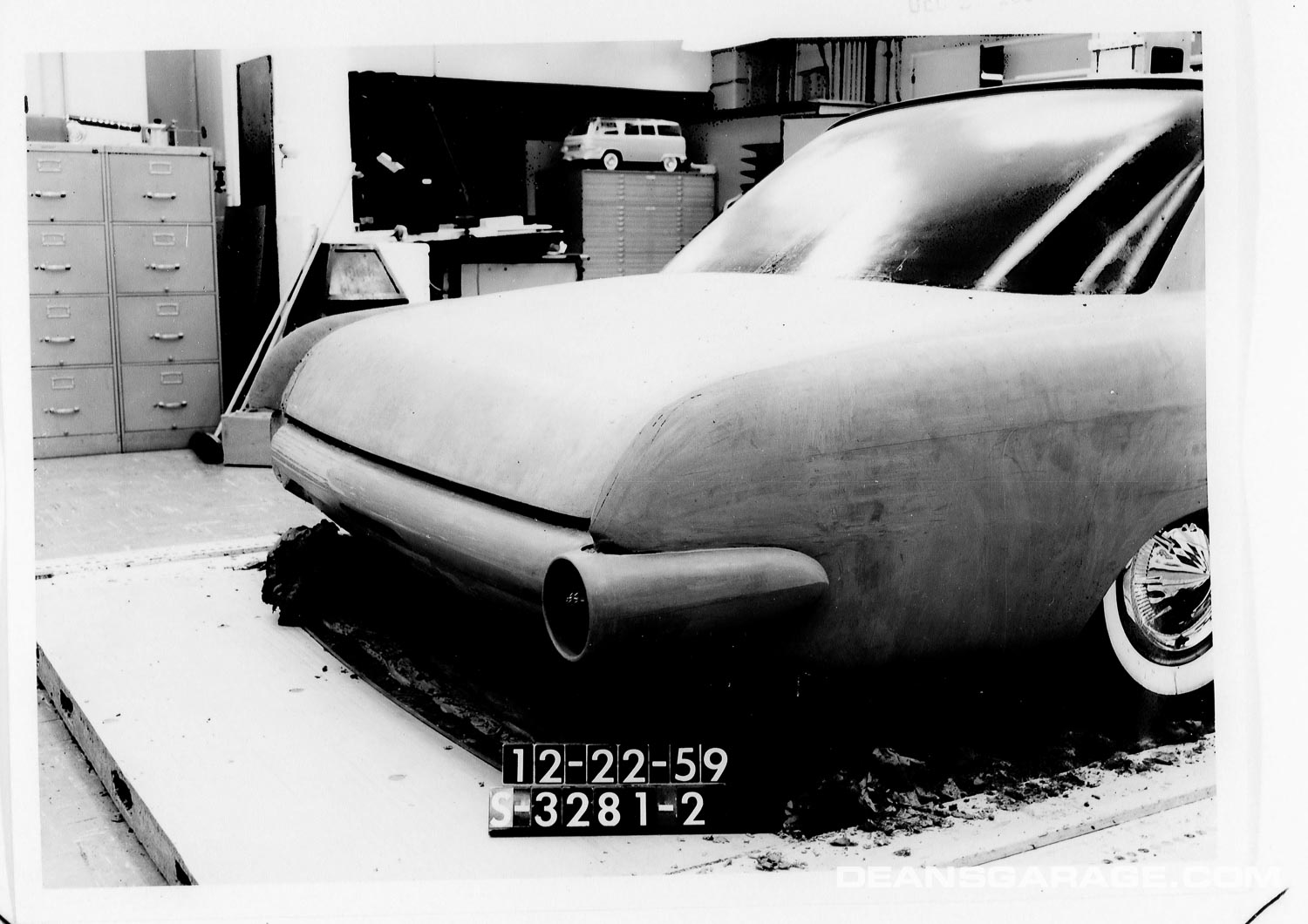

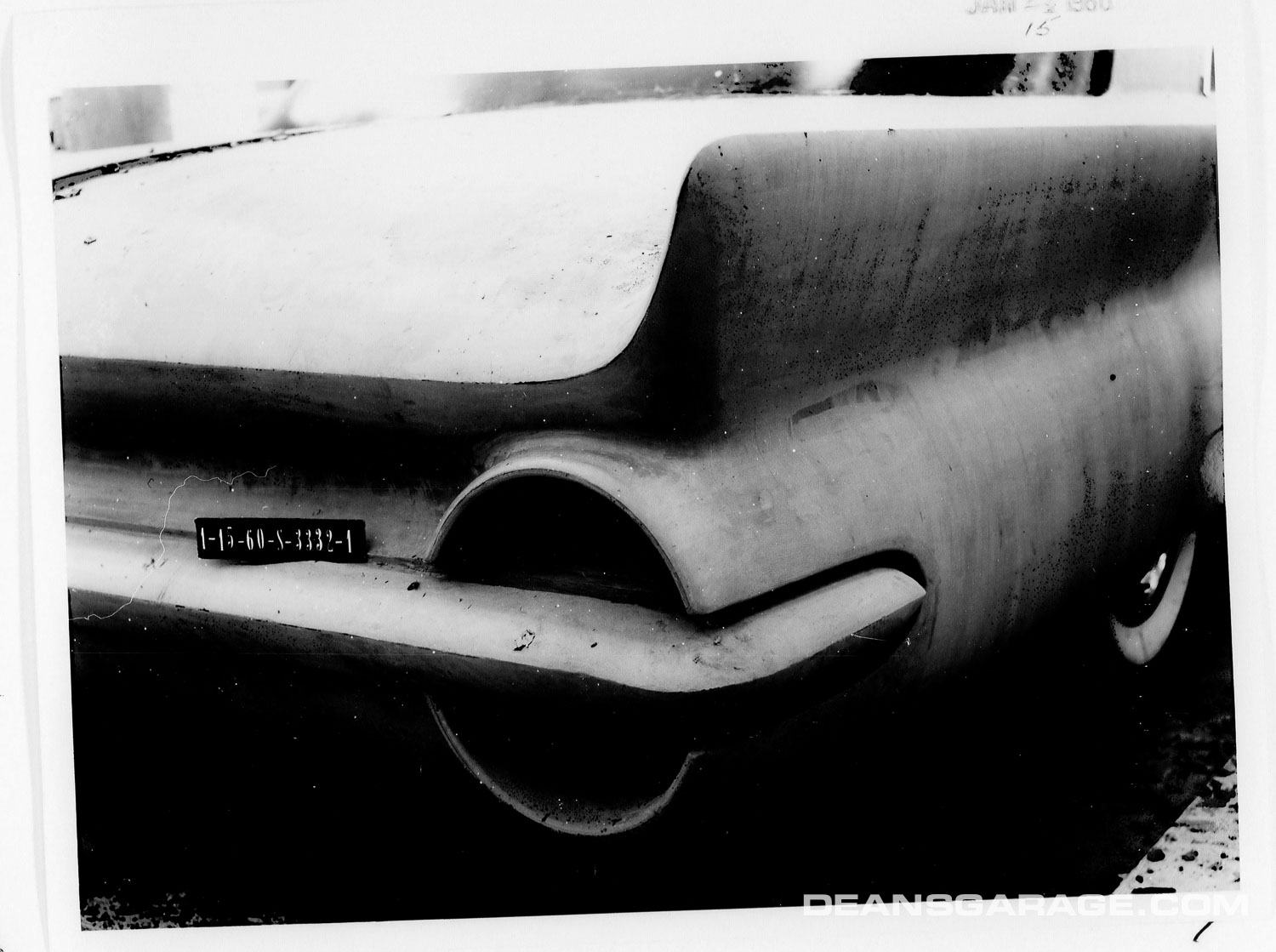

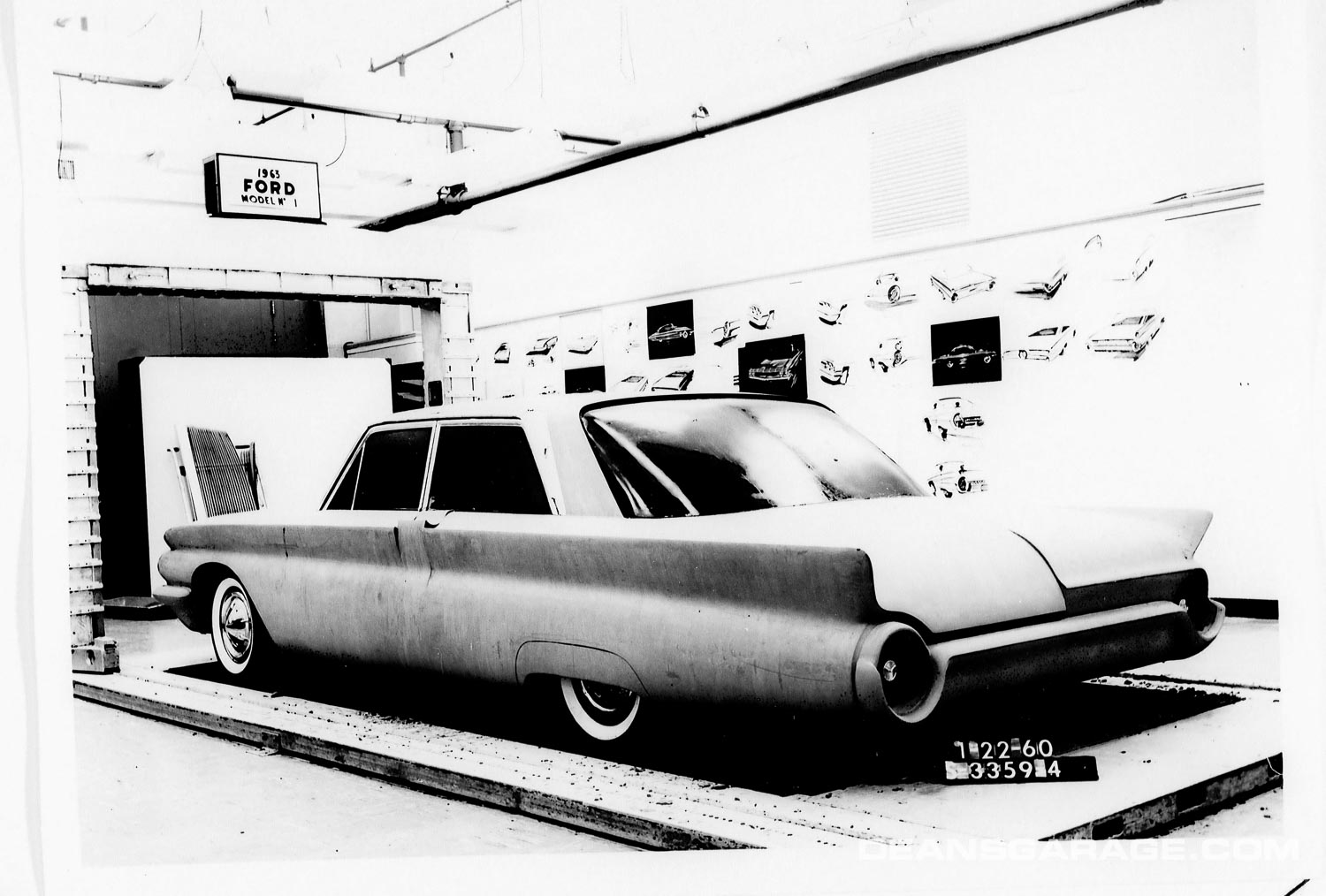

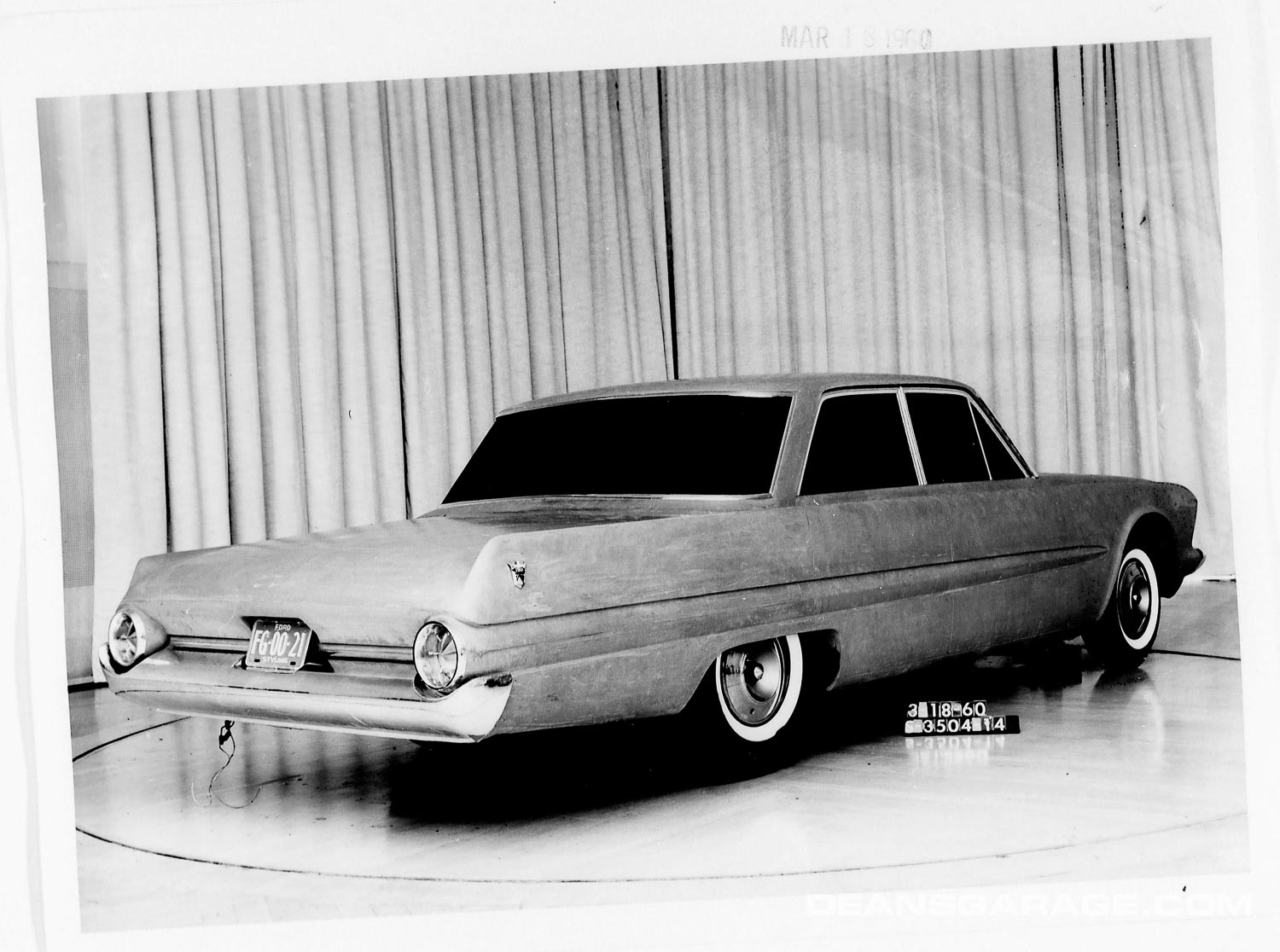

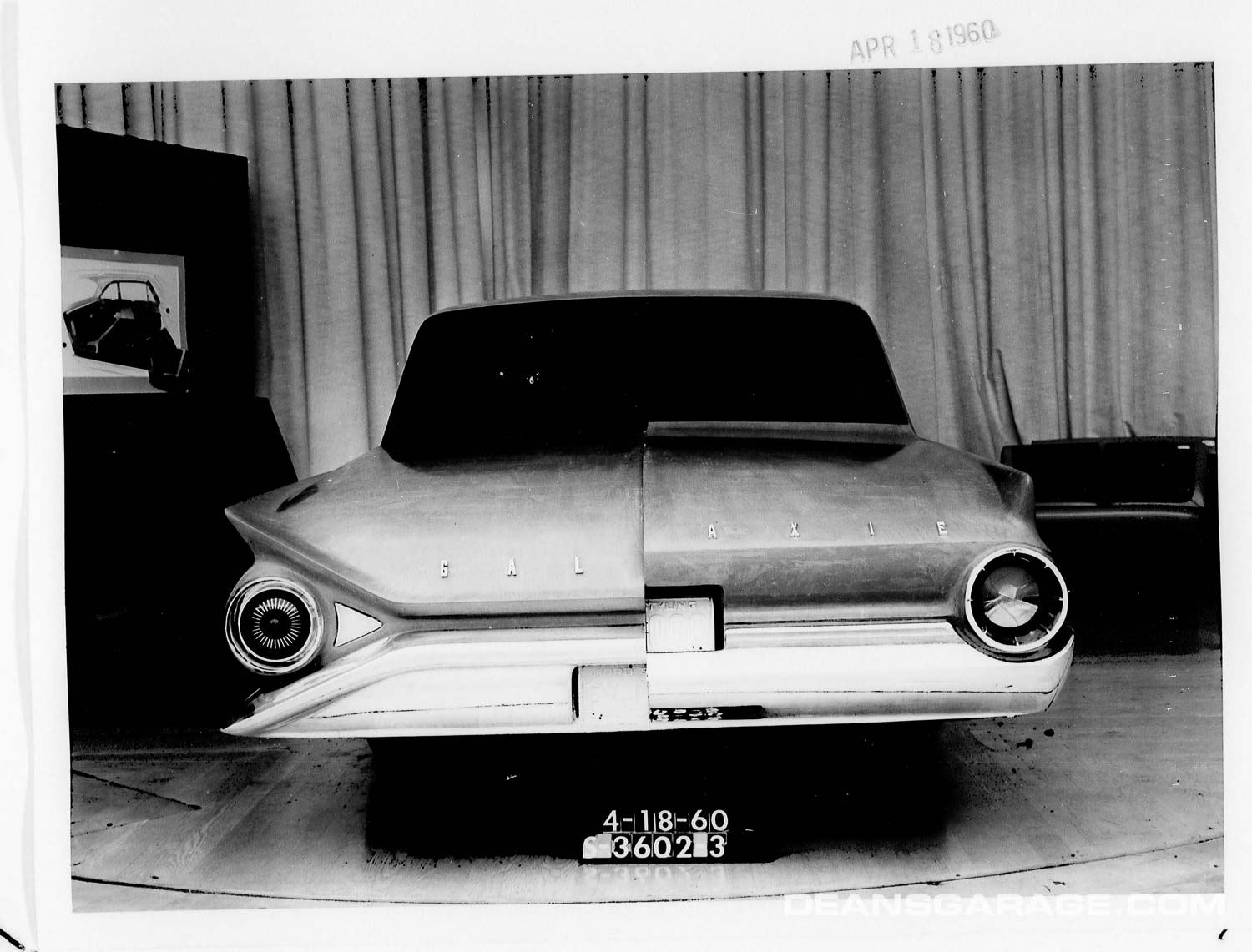

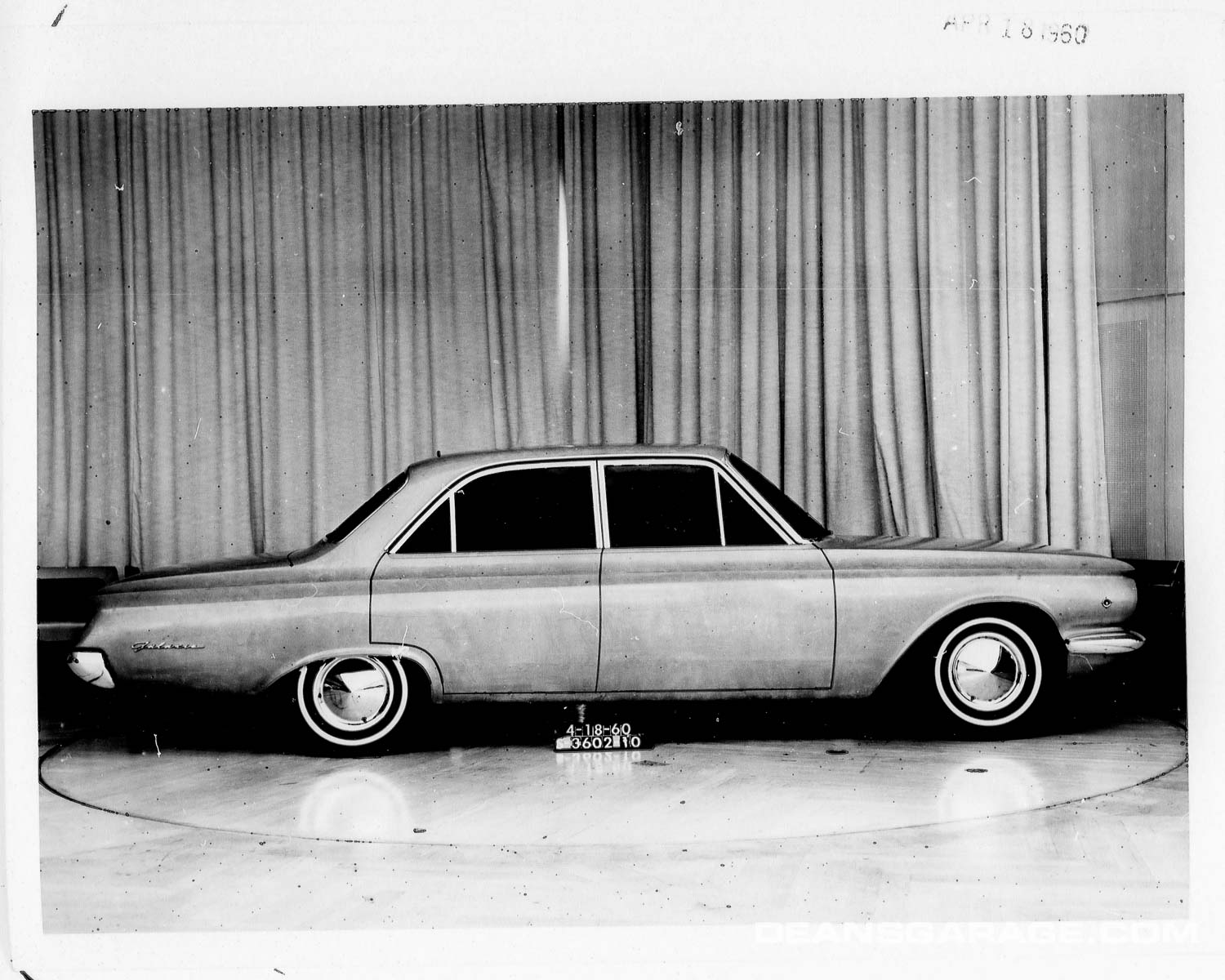

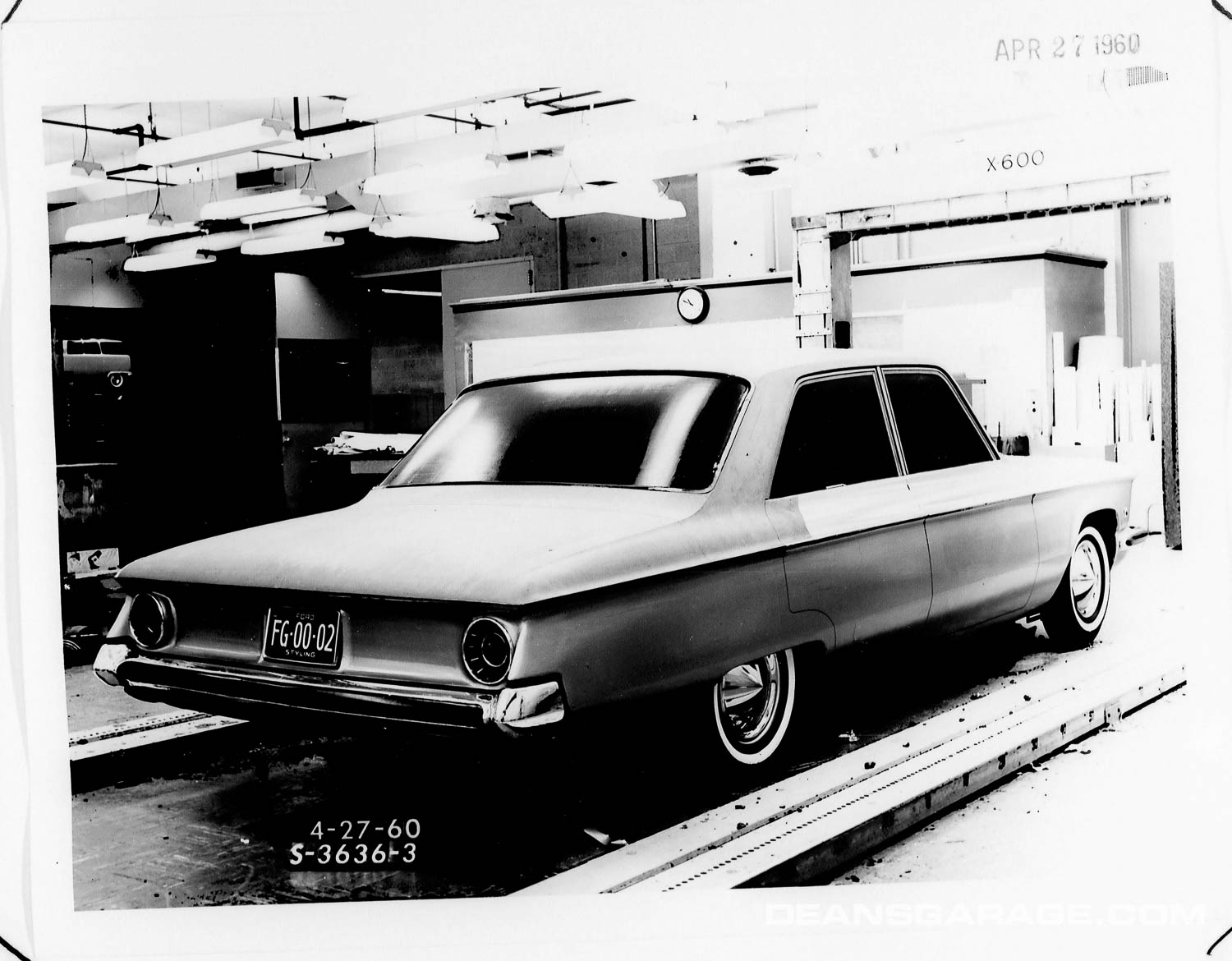

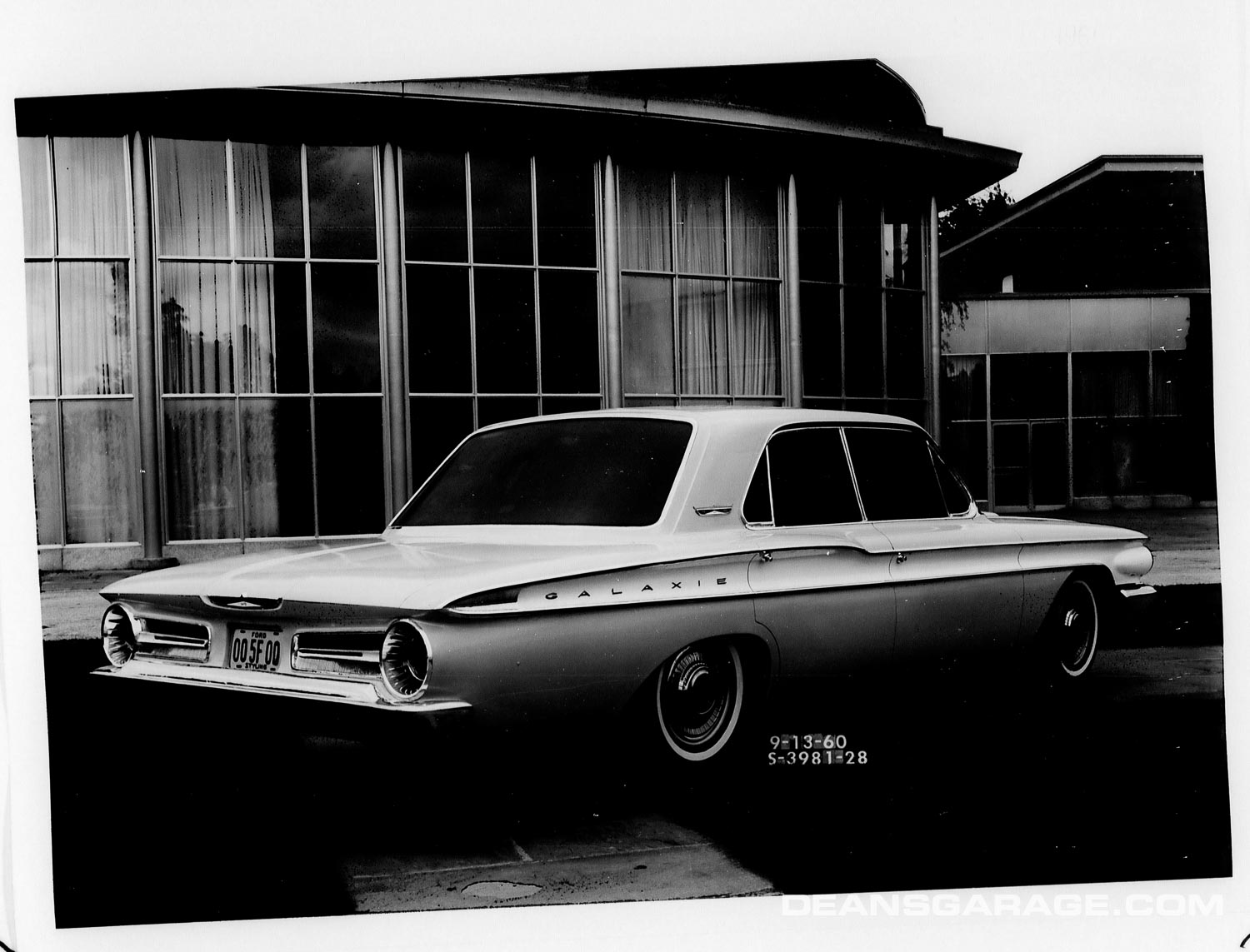

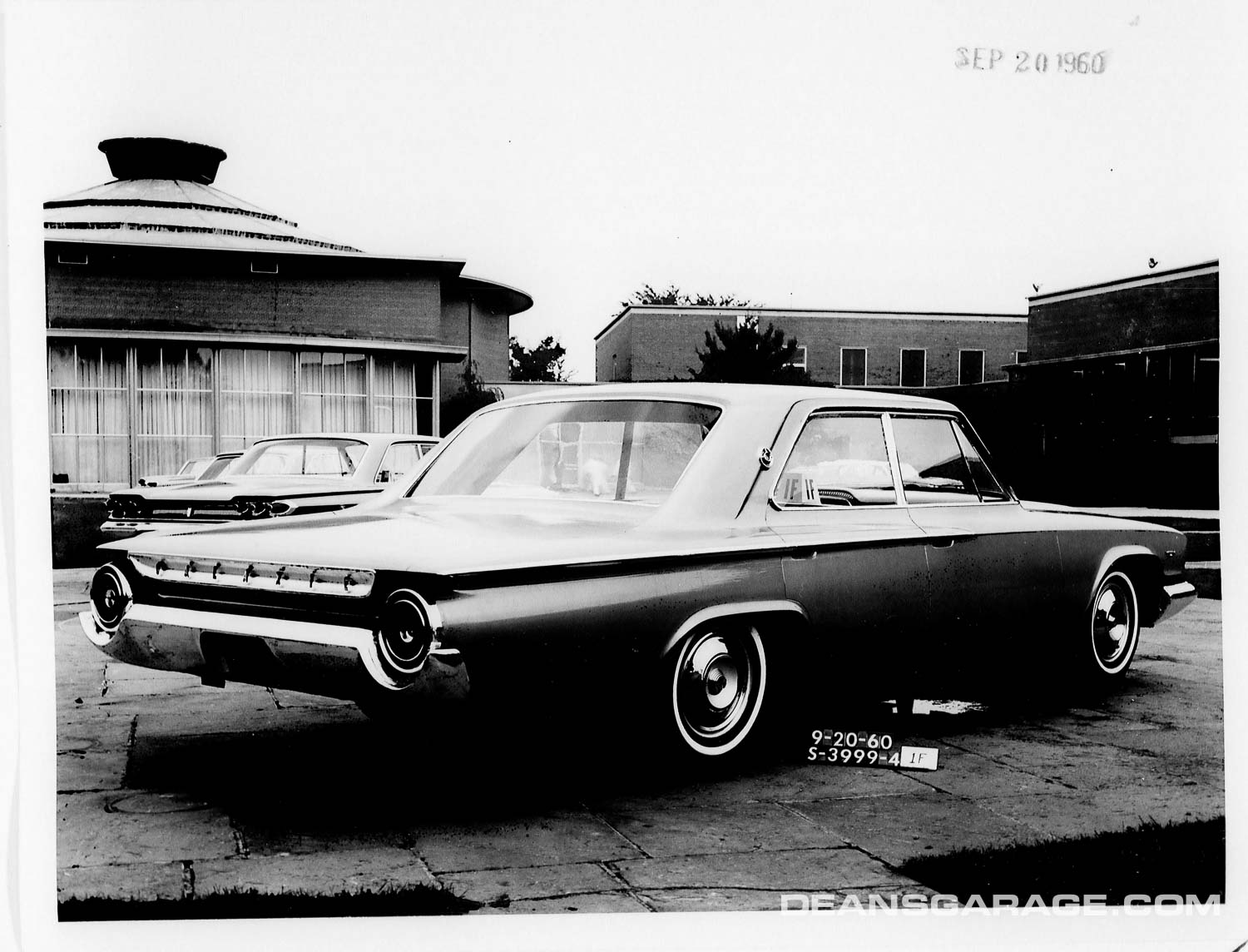

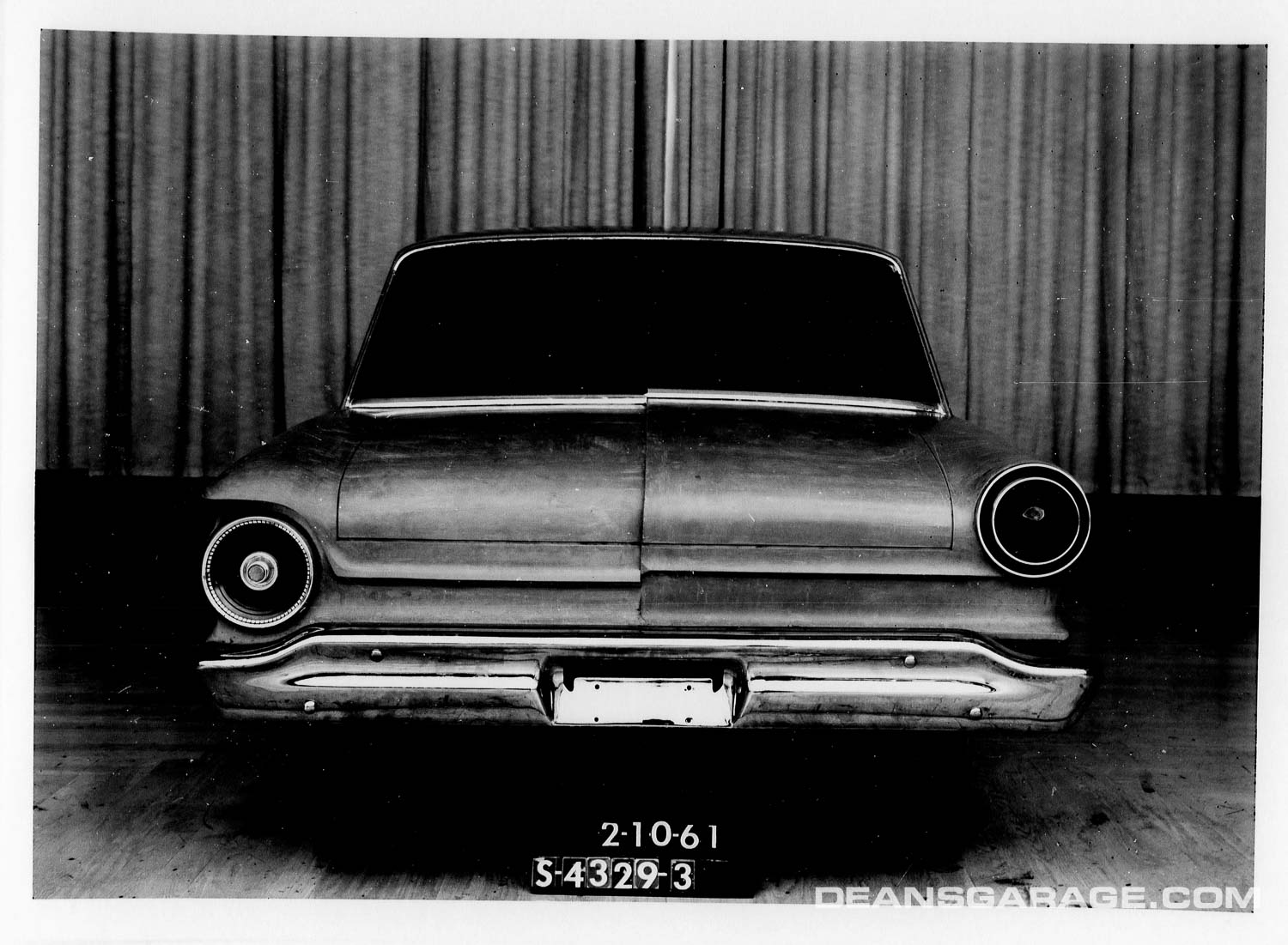

Design of the full sized ’63 Ford began in fall 1959 in Oros’ Ford studio. All designers in all the Ford studios made sketches until a promising sketch, or group of sketches, were translated into a full-sized clay model. That first clay model of a proposed ’63 full-sized Ford looked nothing like previous Fords. It had a sloped rear deck and no sign of the big round Ford tailights. That clay model and many more were rejected by Design Center management or Ford Division head Jim Wright. It does not appear any of them got as far as the Product Planning Committee.

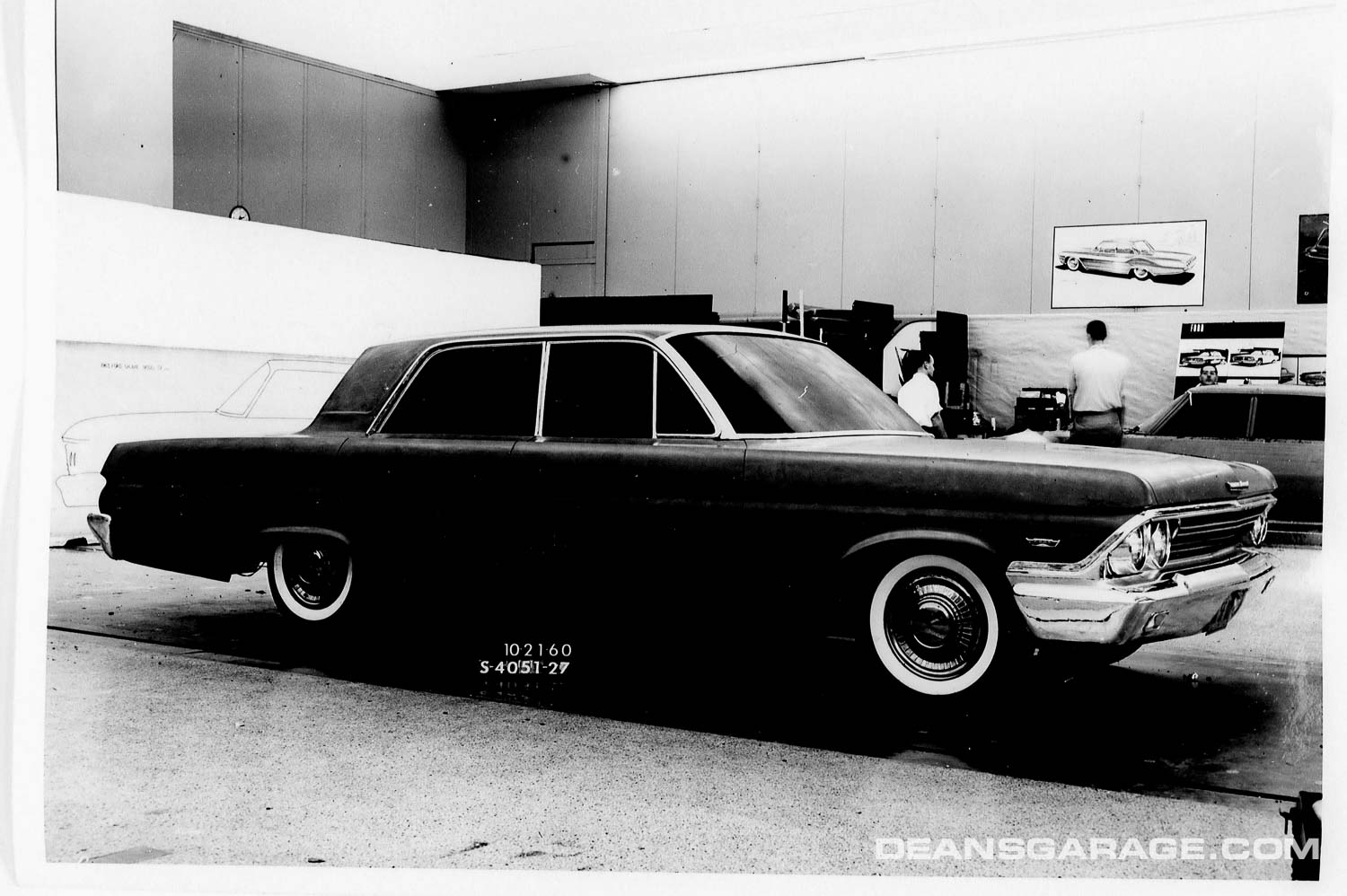

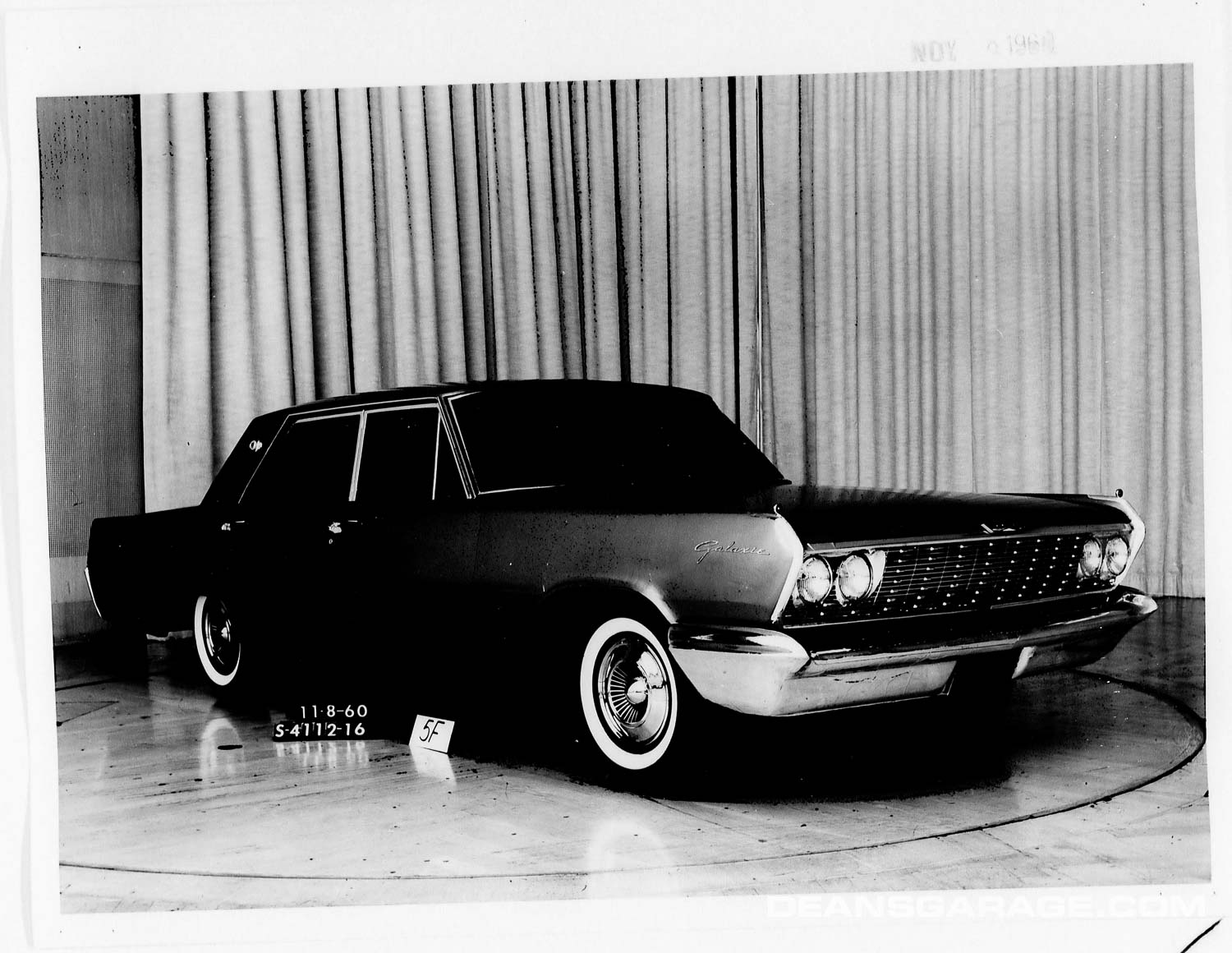

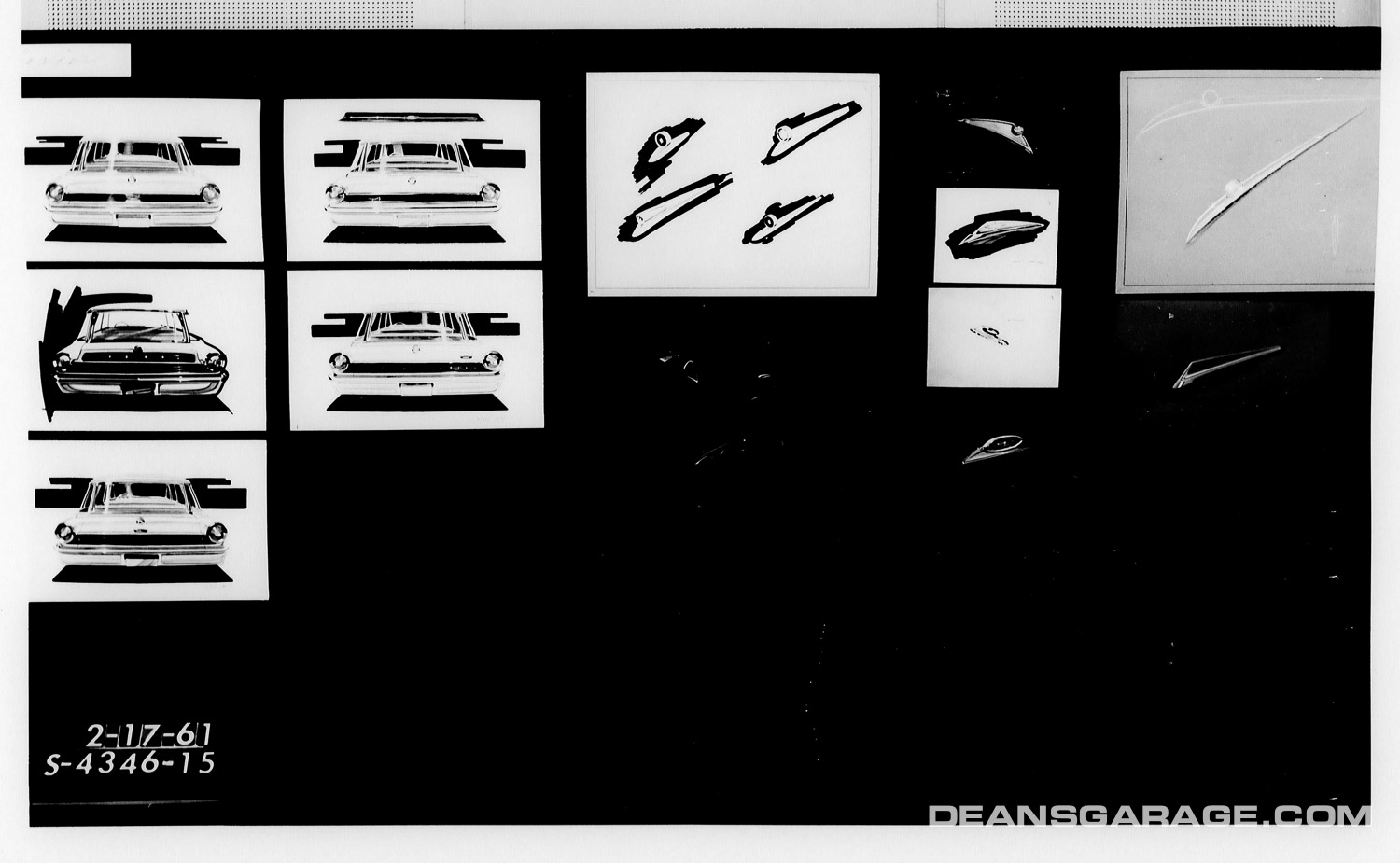

From January through April 1960 the next series of clay models had fins, and by October of that year, Ford studio clay models were similar to the ’61 Lincoln, only to be followed one month later by another full-sized clay model with fins. None of those proposals proved acceptable. By March 1961 Oros had all designers in all Ford studios cranking out proposals for the ’63 full-sized Ford without immediate success. Most of those proposals never got as far as full-sized clay models. It’s now impossible to track what specific designer designed what part on each ’63 Ford full-sized clay proposal because Oros had a habit of constantly reassigning designers from one Ford studio to another until he got the design or portion of a design he was looking for. Oros would often pick and choose from parts of designs proposed by studio designers.

In 1961 Jim Powers found himself in the Ford Preproduction studio even though that was not supposed to be his studio assignment. His exec was Gil Spear, who generally let Powers design what he wanted without supervision. For several weeks, Powers had been working on and had almost finished a 3/8-sized clay model of a future Ford—one he thought could could actually be built given the cost, engineering and material restrictions applicable.

Powers, born and raised in Texas, was another one of those high achievers. He won the Fisher Body Craftsman’s Guild contest four years in a row at the regional and state levels, and also won the national award. He attended Art Center College on scholarships from the Body Craftsman’s Guild, Motor Trend and Ford. He finished Art Center in 2 years 4 months, and then taught there during his last year. He was recruited at Ford by Alex Tremulis, and became life-long friends with Tremulis and his wife. Powers designed the Nucleon and Volante concept cars, the ’61 Thunderbird, and the ’63 full-sized Ford among others. He became the youngest executive stylist at Ford and the youngest enrolled on Ford’s bonus roll, but chose to leave Design Center in 1965 because neither he nor his fledgling classic car collection did well in Michigan winters. After he left, Powers continued to do some design work for Ford, and became a successful industrial designer in southern California. As of this writing, Powers is still with us, but is long retired—and his car collection currently numbers 40 plus.

Powers had his own clay modeling tools and worked closely with clay modeler Walt Amrozi on his 3/8-sized model. Sometime in January 1961, Powers and Amrozi were almost finished with the model. It had been some time since Oros had been downstairs to see what was being designed in the Preproduction studio. One afternoon he came in, saw the model Powers was working on, said “Ah ha—That’s it!” and immediately had Powers’ model moved upstairs to the Ford Production studio, where it became the ’63 Ford. According to Powers, except for trim, his 3/8-sized model was made into a full-sized clay model, and it became the ’63 full-sized Ford with only minor modifications. (Ford Archives has been unable to find photos of Powers’ 3/8-sized model.)

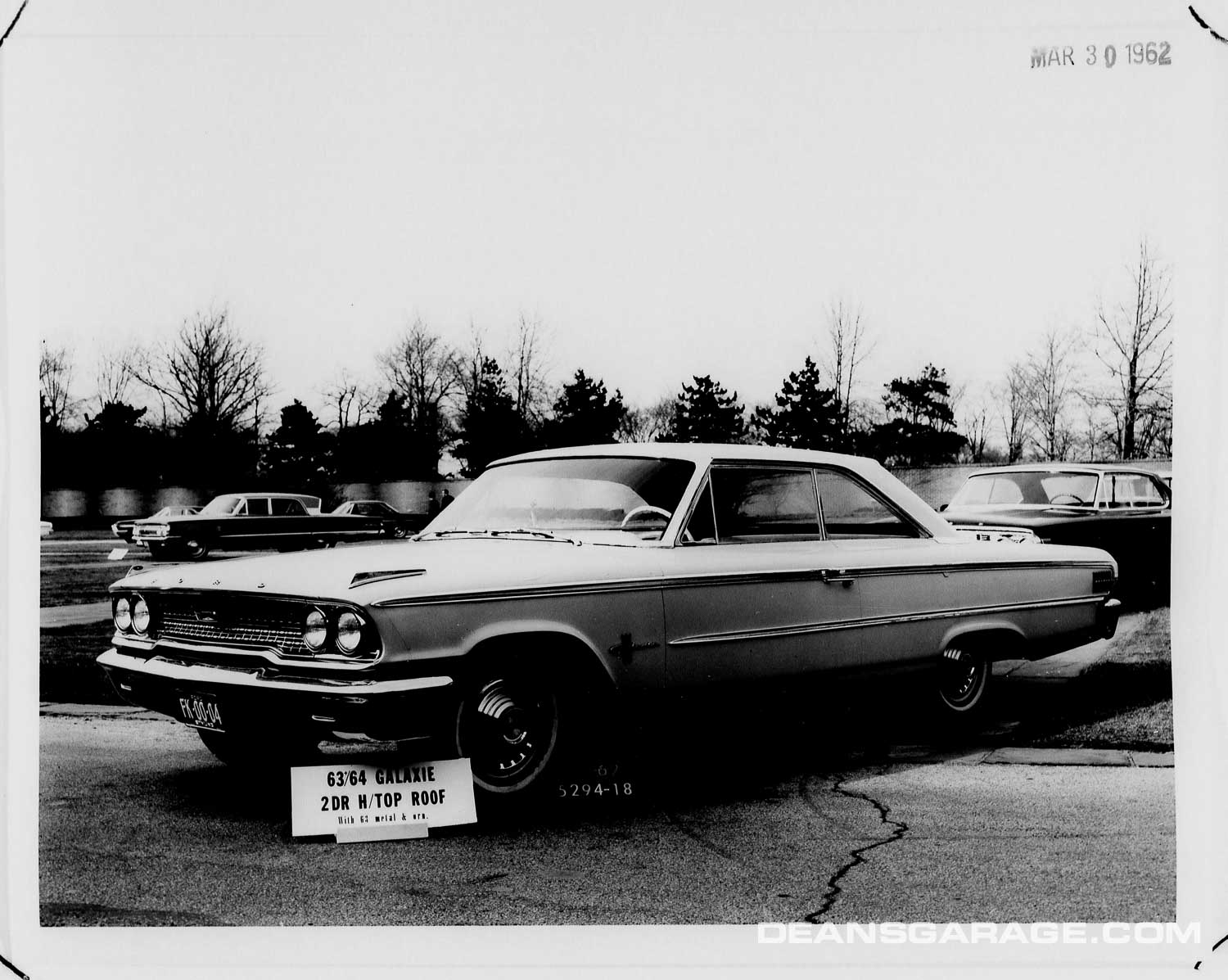

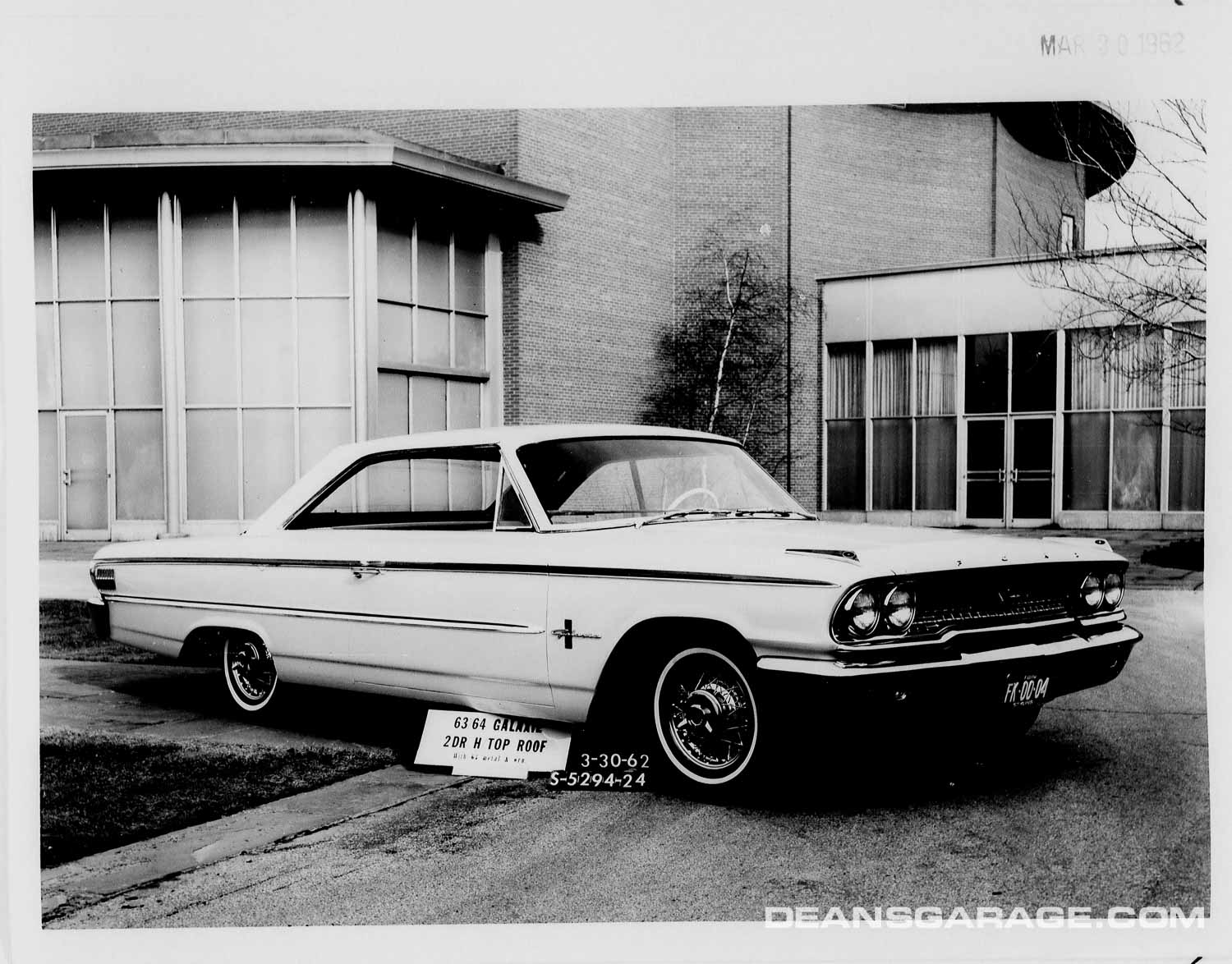

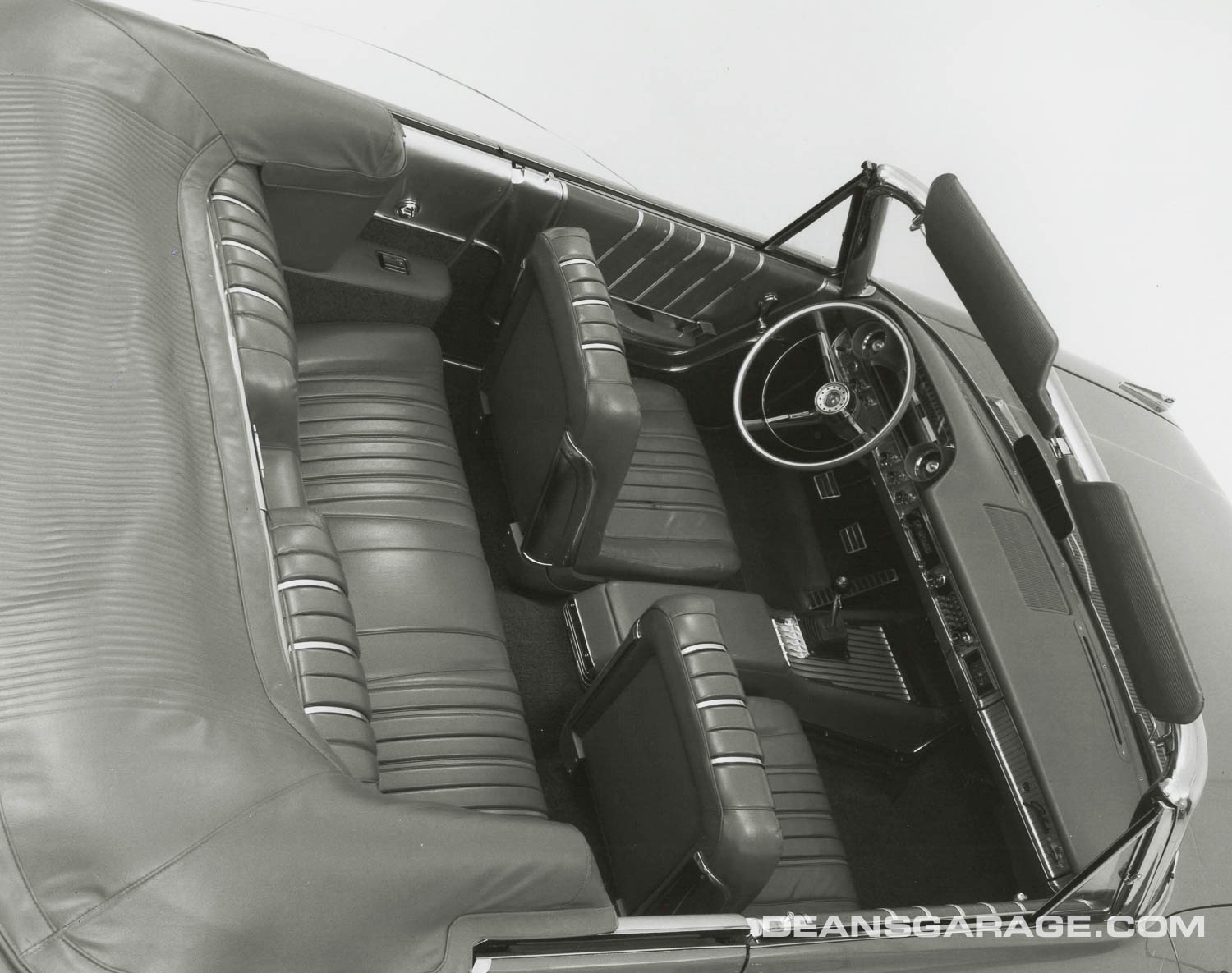

When the ’63 Ford was designed, it was customary to use the squared-off greenhouse from Thunderbird. The idea was to give the full-sized Ford line some of the Thunderbird’s luxury. The fastback roofline was included on a ’63 design proposal in March 1962, but wasn’t used in production until midyear on the ’63 ½ Fords. According to Oros, the fastback design was used because it looked “more sporty.” Powers was also the designer who came up with the fastback C-pillar design for the ’60 Ford which was also used on the ’63-1/2 Ford. At the time, Powers was assigned to the Ford Station Wagon studio. (For the 1960 Ford, Powers thought Oros ruined his fastback roofline design by putting three little circles on it, which Powers refers to as “do-dads.”) Iacocca may also have played a part in the ’63-1/2 full-sized Fords, including use of the fastback roofline.

Photos: Ford Design

Books by Jim and Cheryl Farrell

Ford Design Department—

Concepts & Showcars

1999, 10×13, 400 pages, Fully indexed

900 photos. Includes 150+ designers and sculptors, and highlights 100 concept cars.

ISBN 0-9672428-0-0

Lincoln Design Heritage:

Zephyr to LS (1936-2000)

2021, 10×13, 480 Pages, Fully Indexed

1,600 photos and illustrations

ISBN 978-0-9672428-1-1

The Ford book is $50 plus $7 S&H (US). The Lincoln book is $85 plus $10 S&H (US). Both books bought together are $110 plus $17 S&H (US). To order, email: cfarrell57@gmail.com

Excellent write up Gary, about all the machinations that automotive design goes through, in this case with Ford’s bread and butter product. When looking at all those iterations, it sure looks like they picked the best in the end, although that judgement may be the result of the public (us) never seeing those failed proposals and becoming accustomed to what a “proper” Ford should look like…

Thank You

What a well done ,superb skill of research and outstanding historic images.

I think some readers here will take exception to your observations that the 1963 Ford shared bodies with 1960-1964 models. This is simply not true. The 1960-1962 shared bodies and the ’63-’64 shared bodies. They all shared the same ladder-type frame since 1957.

The mid-size Fairlane debuted for the 1962 model year, not ’63. Like the Falcon, it had to wait for its convertible and hardtop versions to appear.

I’m glad they got it right. Some of the those early pix looked nasty.

Very interesting.

The issue of rooflines is a question: I and many racing enthisiasts had always heard that the so-called “fastback” roofline of the ’63 came as a result of finding out that the squared-off roofline was like unto a brake on NASCAR tracks – and that Pontiac had yet again stolen a march from Ford with its “semi-convertible” roofline. THus the “63 1/2” roofline introduction, which put Ford back in the running in NASCAR. Note that the Fords shown in the racing picture are all “63 1/2” models…?

I have always felt that the ’63 full-size Ford was one of the best Ford designs of the ’60s, looking crisp, clean and modern. It is interesting to see how dated and unattractive so many of the concepts done in ’59 and ’60 look by comparison. The list of Ford designers must not be complete, as I see no reference to either Gale Halderman or David Ash.

The list of designers is complete as of early 1961. Ford records show Dave Ash and Gale Halderman were assigned to the Ford studio soon after. Jim Farrell

I am sorry to report, Jim Powers died May 12, 2023