Design of the 1961 Lincoln, Part 2: Reassessment and Redirection

By Jim and Cheryl Farrell

When Mills took over (again) as head of Lincoln Division, he spearheaded a study to determine why Cadillacs sold better historically than Lincolns. Mills’ study determined the primary reason was because Lincoln did not have design continuity from model to model; each model was totally different from the last. As a result of the study, Lincoln’s design leaders Gene Bordinat and Don DeLaRossa decided the ’61 Lincoln proposal being designed in their studio had to show continuity with the prior (’58) Lincoln. Their proposed ’61 Lincoln did look similar to the ’58 Lincoln—and it had the continuity that was seen as so important.

When Ford began selling its stock to the public in 1956 all of its divisions were required to make a profit each year. When they reviewed the Lincoln studio proposal, those on Ford’s Product Planning and Executive Committees did not believe a ’61 Lincoln that looked anything like the ’58 Lincoln had any chance of making profit. The Lincoln studio proposed ’61 Lincoln was shot down.

When McNamara met with Mills, McDonald and Johnson and told them he favored discontinuing Lincolns, Ford’s Product Planning and Executive Committees had already turned down the Lincoln studio’s proposal and they had tentatively selected an earlier Lincoln concept car called the Marlin as the ’61 Lincoln, although the Marlin was modified at the request of some committee members.

After McNamara scared the daylights out of McDonald and Johnson, he and Mills began planning what to say to Ford’s Product Planning and Executive Committees, and how to encourage them to choose Engel’s Thunderbird proposal for the ’61 Lincoln. But first they decided they had to display a united front and their proposals had to be logical and well-researched. On December 19, 1958 the two committees met in closed session to decide the fate of Lincoln.

When the December 19 meeting began, several committee members referred to the tentatively approved Marlin as “uninspired.” Ernie Breech, Ford’s executive VP, then suggested a new design be developed for the ’61 Lincoln based on the X-100 or the XL-500 show cars. There were also suggestions that the ’61 Lincoln be made “special” with parallel action doors, sliding or removable roof panels, and that its cost be cut by using more interchangeable parts with Thunderbird. None of those ideas got traction. Then McNamara and Mills began their presentation.

McNamara started out by reporting that Lincoln’s last year of profitability was 1940, and that during the last 18 years Lincoln had lost $184.2 million. Next, Mills then told committee members that Lincoln’s quality, reputation and owner loyalty were terrible, that Lincoln’s dealer network was no where near as strong as Cadillac, and it wasn’t likely to change for a long time. Lincoln’s repeat sales were embarrassing as was its resale value. In the past 10 years, according to Mills, Cadillac had increased its market penetration from 1.6% in 1950 to 2.9% in 1958, while Lincoln’s went from .4% in 1950 to .7% in 1958. 35% of Cadillac sales were to previous Cadillac owners, while Lincoln’s rate of repeat sales was a miserable 10%.

Henry Ford II followed up on the bad news from McNamara and Mills with his own opinion that, based on what he had heard, Lincoln was a waste of Ford Motor Co.’s money.

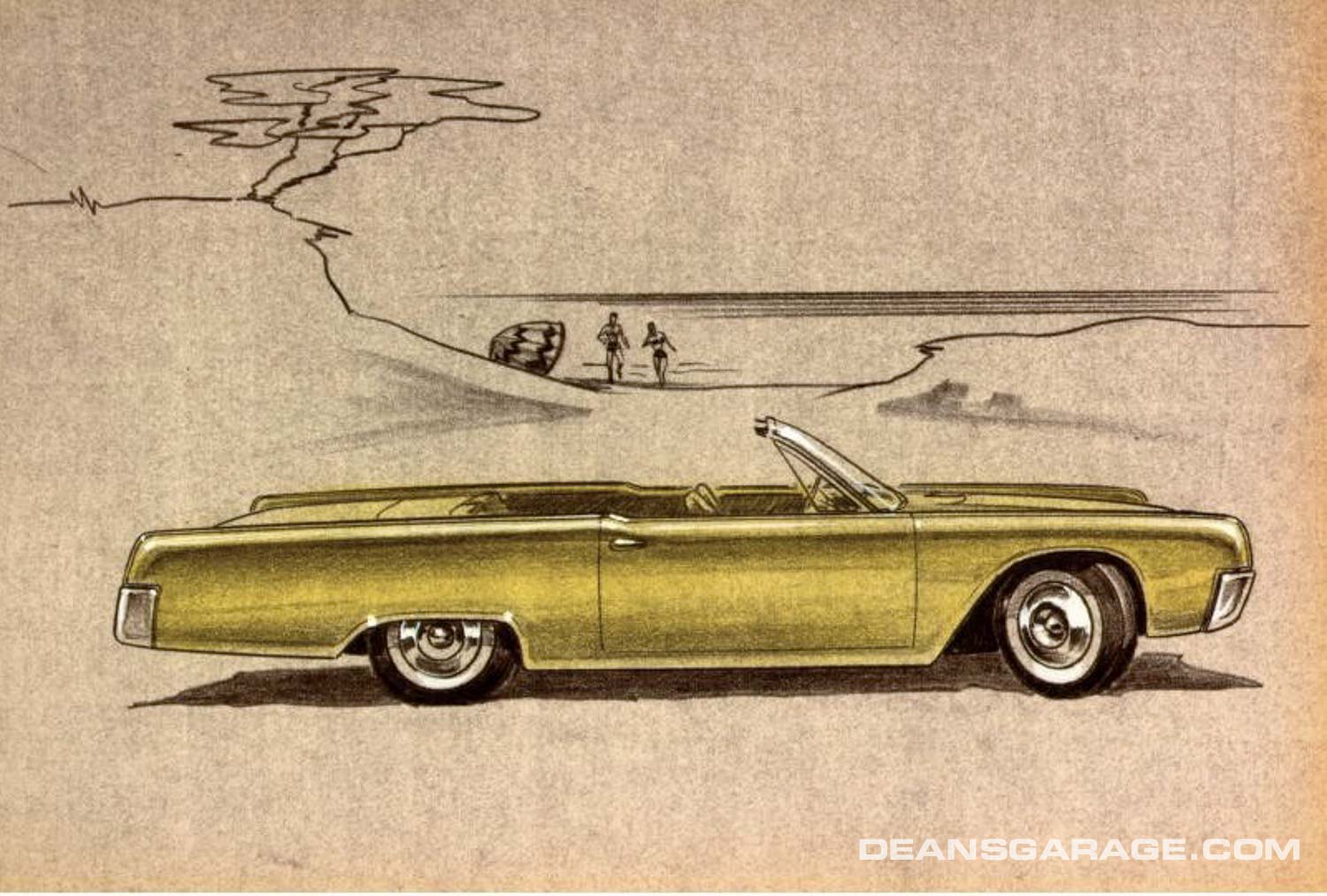

McNamara then told committee members he saw four alternatives of what to do about Lincoln: 1) continue marketing Lincolns and Continentals as before during the coming 1961 model year; 2) drop all Lincoln models and market only the Continental in three models, a 2-door hardtop, a 4-door hardtop and a 4-door convertible; 3) develop a specialty-type 4-door car similar to the Thunderbird; 4) stop producing Lincolns and Continentals completely and vacate the high-priced market.

The idea of producing an upscale Thunderbird, making it 4-door and branding it as a Lincoln got some interest, until McNamara gave estimates as high a 30% reduction of Thunderbird sales as a result was forecast. By the end of the meeting support for a 4-door Lincoln based on the Thunderbird evaporated because no one wanted to do anything to hurt Thunderbird sales.

As the meeting ended, Mills was directed have his division study the alternatives and report back with recommendations at the next meeting.

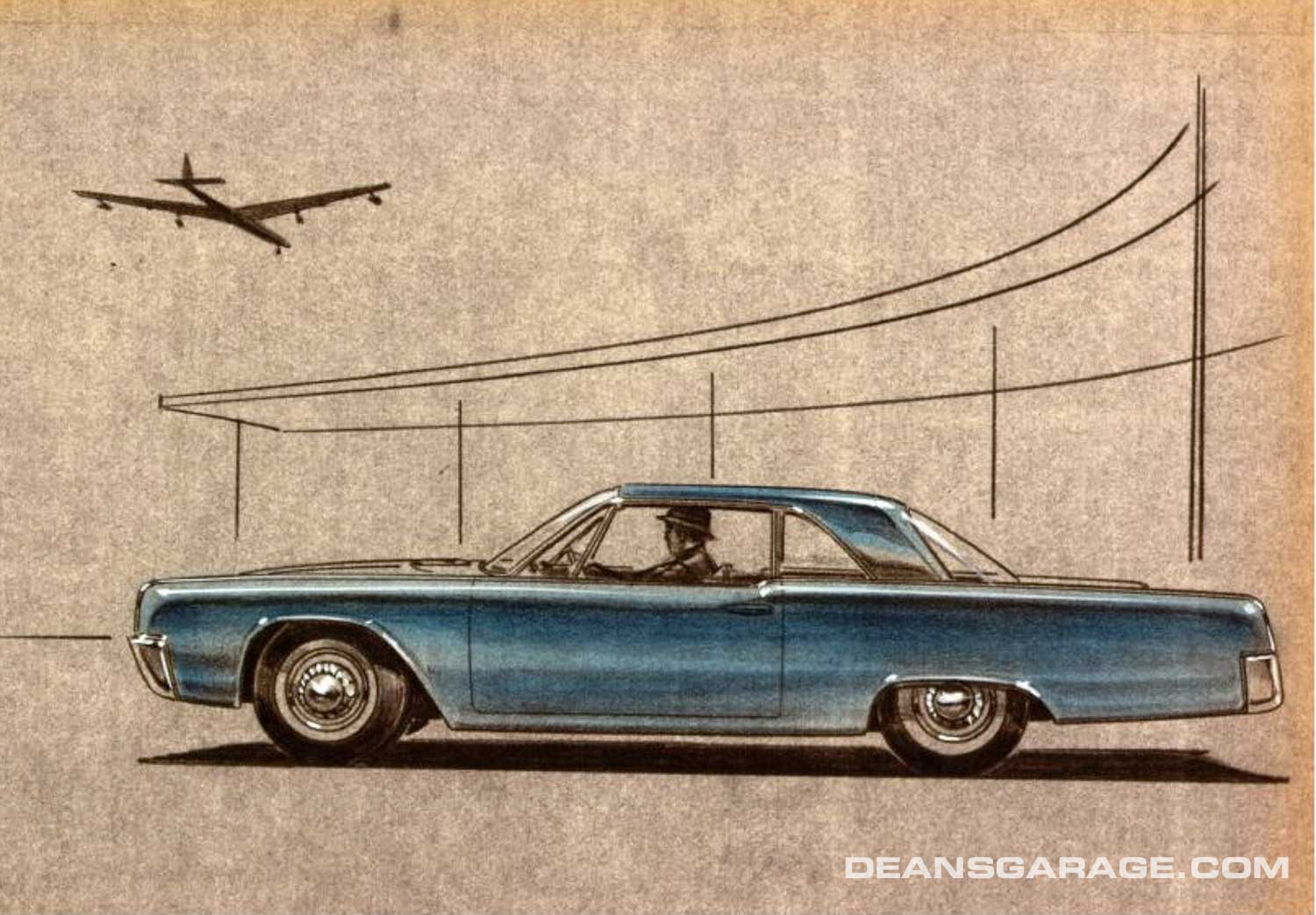

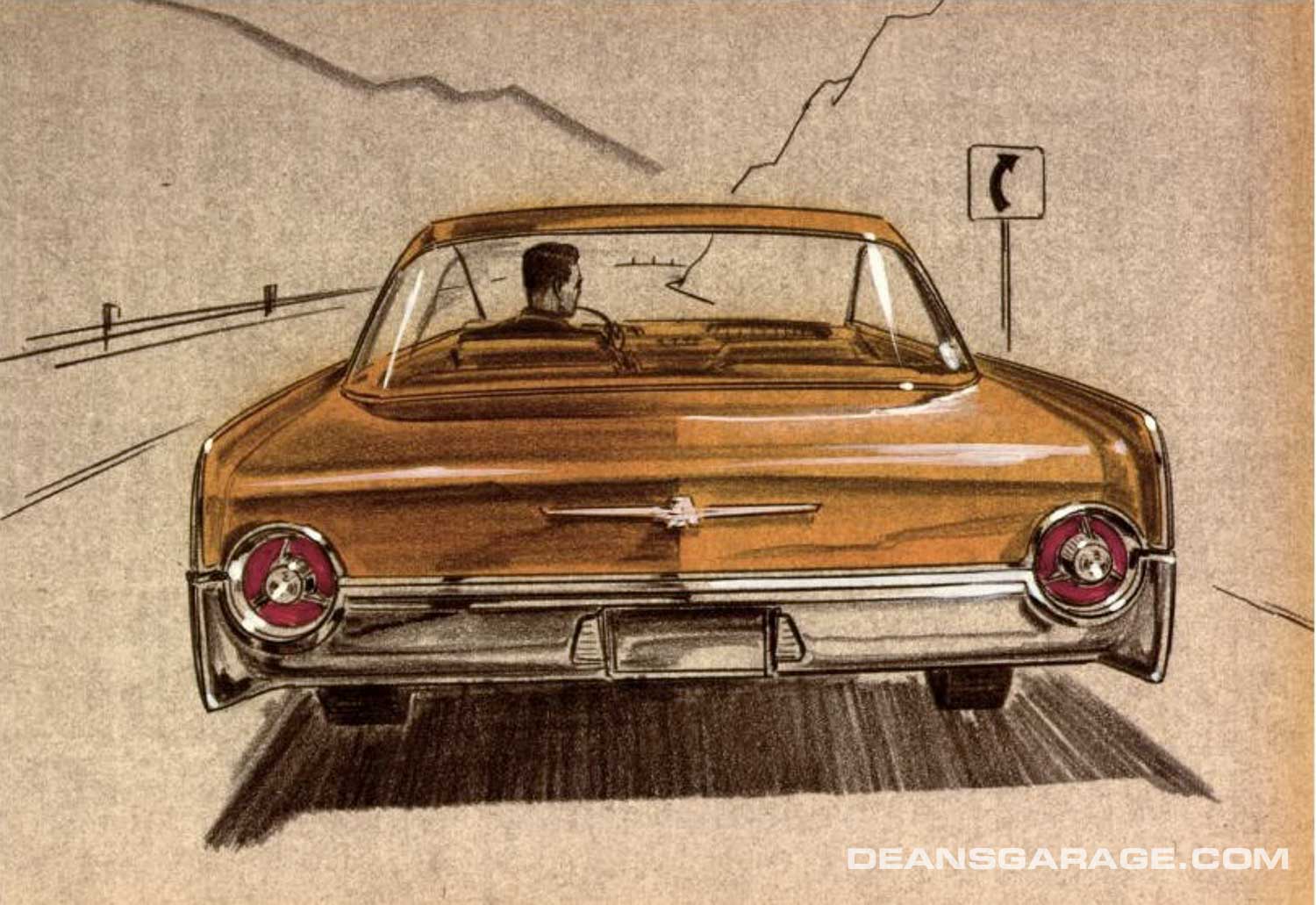

After the Ford studio’s proposed ’61 Thunderbird had been selected, none of Lincoln’s engineers were aware of the decisions under consideration by Ford’s Product Planning and Executive committees—except that McNamara threatened to discontinue Lincoln. As a result of what McNamara said about stopping production of Lincolns, Johnson decided to lengthen Engel’s proposed Thunderbird by only ten inches and add two more doors. Johnson was afraid to add any more length to the car because of McNamara’s original instructions to make it a four-door car, but not appreciably lengthen it from the two-door size it started out as. Johnson had a real fear McNamara would follow trough with his threat to discontinue Lincolns if they made the car too much longer than the 2-door. Johnson thought the only way he could make Engel’s Thunderbird proposal a 4-door was to lengthen only by the bare minimum.

When Engel’s clay model was rebuilt as a four door, the hopup was put back in the belt line just in front of the termination of the rear doors. At the same time, Engel decided to eliminate the vertical part of the chrome caps.

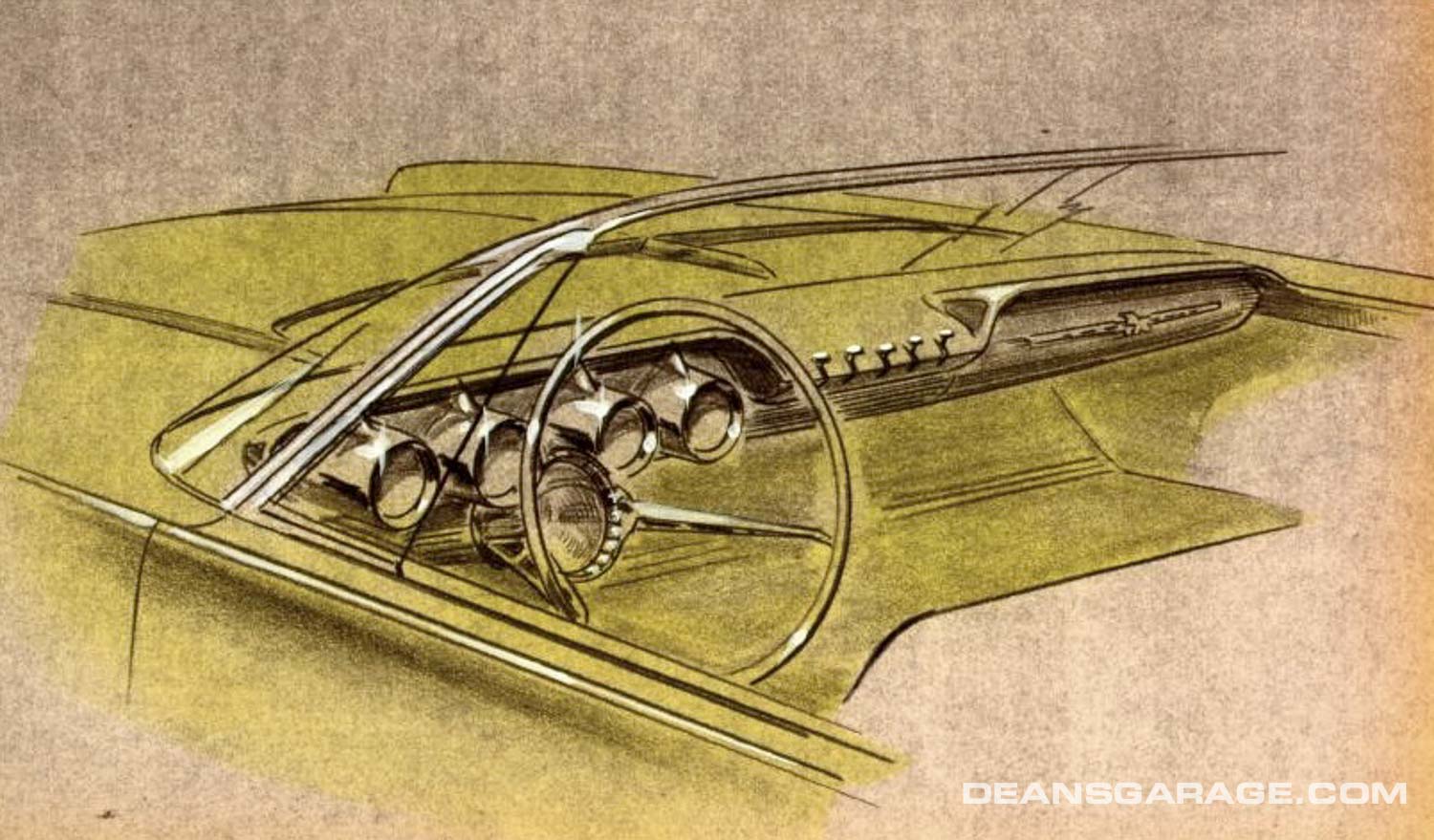

When Johnson got to the Styling Center, he asked Engel’s designers to prepare a 4-door seating buck. Johnson left but later got a call from Najjar telling him the seating buck was ready. The next morning he went to the Styling Center to see the seating buck. It had four-doors and the seats were built to Lincoln seating specifications, but the rear seats were more rounded at the corners. The front seat was fine, but back seat entry was terrible—Johnson couldn’t enter or exit without hitting his feet. The only thing Johnson could think of was to recommended reverse opening rear doors. When he made that proposal, Johnson also proposed to do away entirely with the B-pillars and to lock the doors to the floor and to each other, but they ultimately decided against that because of concern that McNamara might still cancel Lincoln if it became too complicated or too costly. The rear “barn doors,” as Johnson called them worked fine and only required an extra 10-inches to Engel’s 2-door proposal.

For the January 5 meeting of the Product Planning and Executive committees, Mills and Lincoln division prepared a blue paper setting out their division’s analysis of each option. The blue paper concluded that by stopping production of Lincoln altogether there would likely be problems with dealers and even with Ford employees. There was also a fear the public might suspect problems with the rest of Ford’s car lines, especially Mercury, and that some people might even stop buying Ford products. Mills had determined that Lincoln’s fixed costs of $18 million, and possibly more, would have to be absorbed by Ford’s other car lines if they stopped building Lincolns. The second alternative was the option Mills recommended as having the best chance for Lincoln to profitably continue building cars in the “high-priced field.”

The decision to build Engel’s Thunderbird proposal as the new ’61 Continental was formally made at the January 5 Product Planning and Executive Committee meeting, but it was also decided that during the next design cycle Lincoln had to make a profit or go out of business. The committees also decided that the name Lincoln was damaged goods, and to increase prestige, future Lincolns, if there were any, should be branded as Continental only.

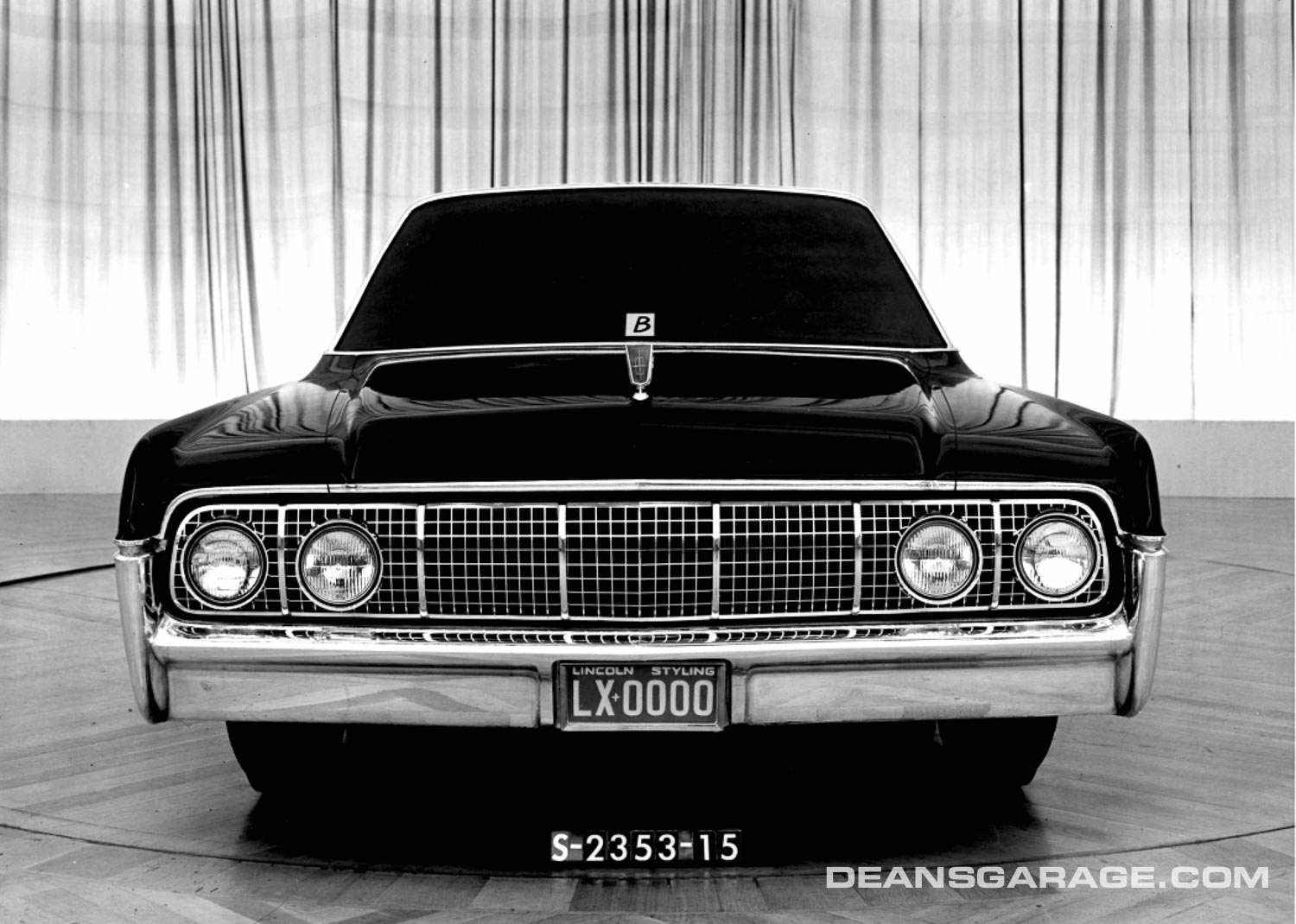

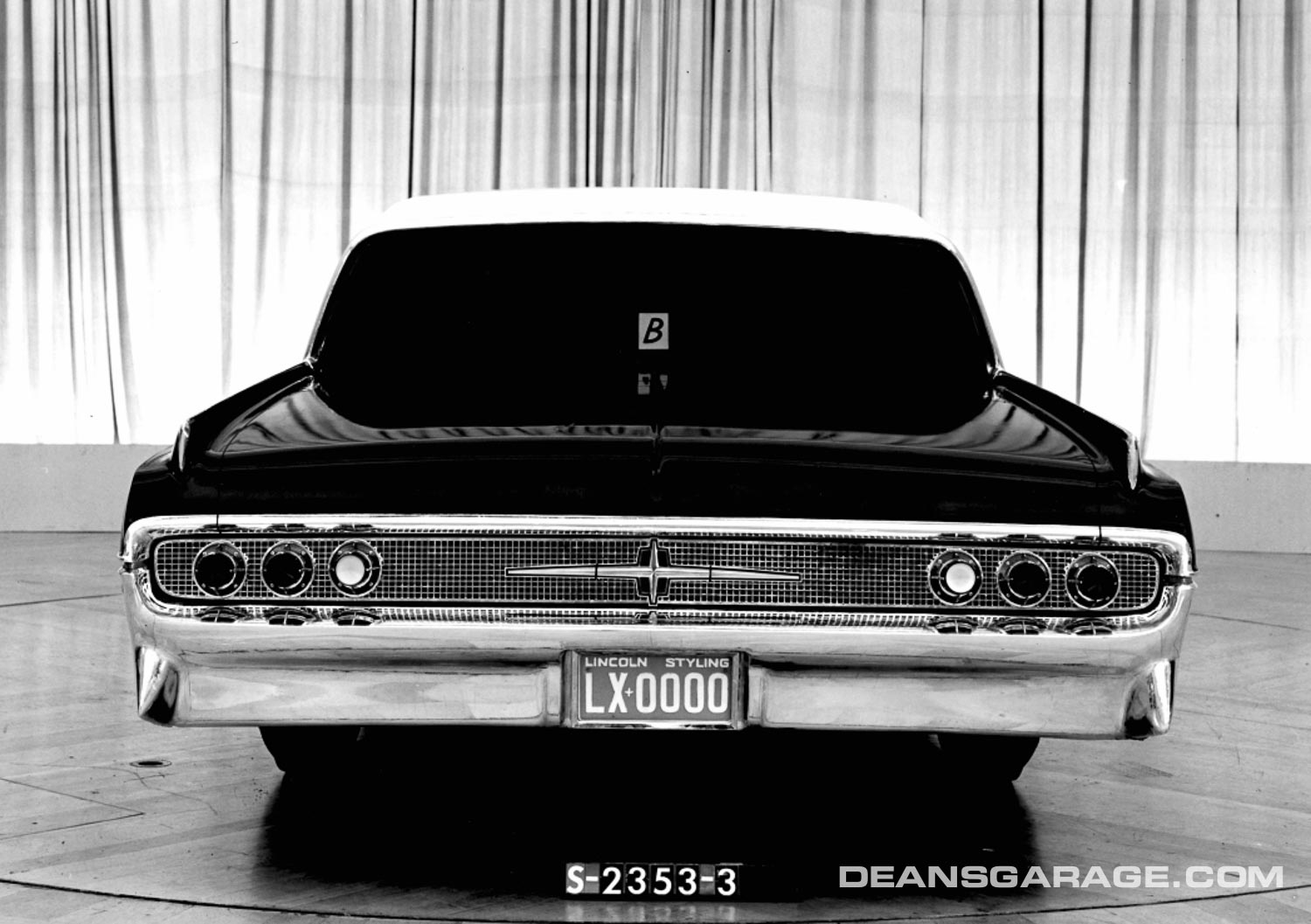

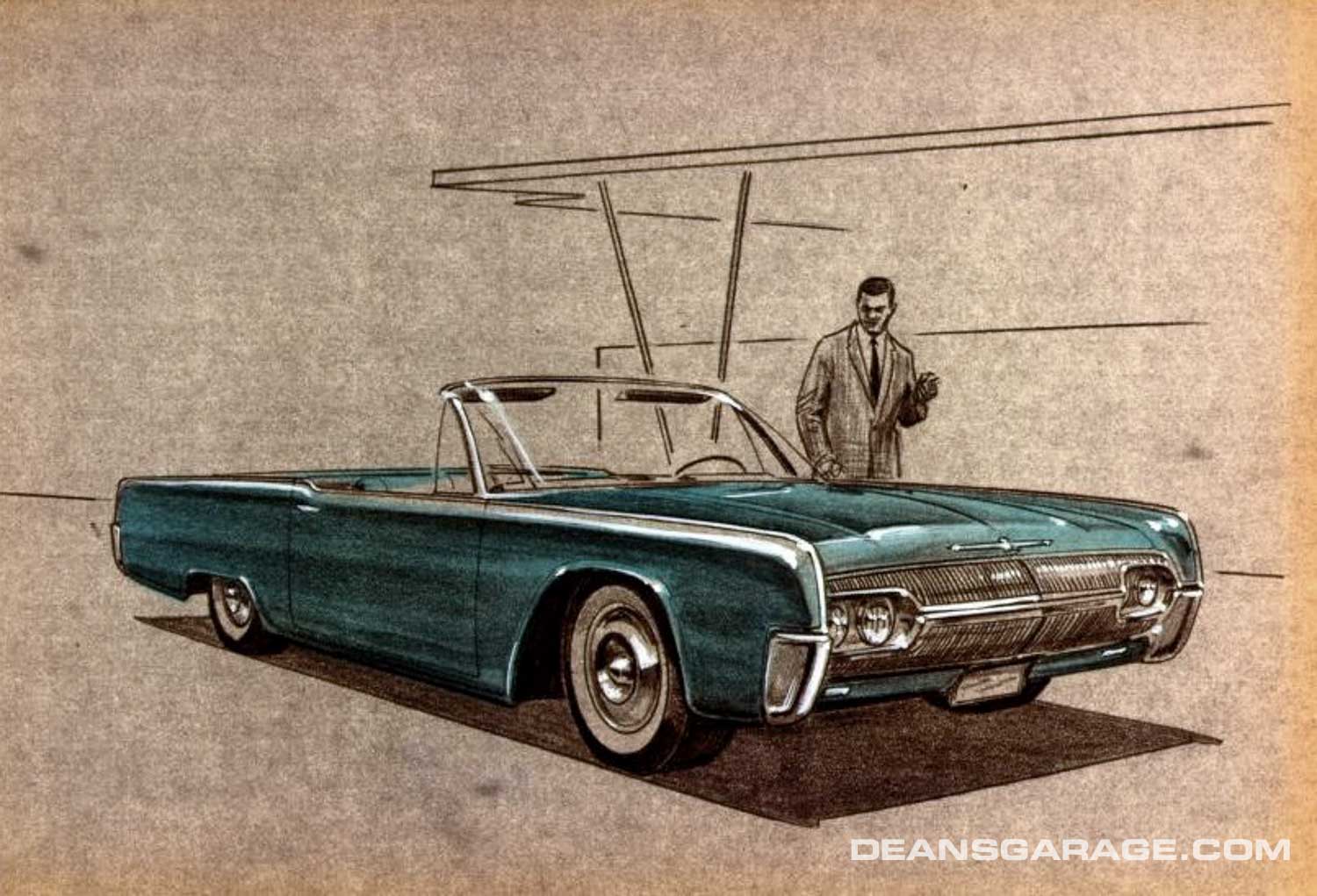

After Engel’s revised 4-door 1961 Lincoln proposal, with its barn doors, was approved by the Product Planning and Executive committees, it was moved upstairs to the Lincoln studio to prepare it for production. There, Bordinat, DeLaRossa, and their studio designers developed trim and ornamentation for the car—and continuity of design had to start over again with the ’61 Lincoln.

The 1961 Lincoln body style was produced until 1965. Except for 1964, there were few changes made, but that was on purpose. In 1964, wheelbase was increased three inches allowing more backseat leg room; a new decklid and a deeper trunk resulted in increased luggage room; curved side windows were eliminated increasing inside room; and redesign of the roof resulted in more headroom. Today, 1961–65 Lincolns are recognized as some of the finest and best designed cars ever produced. More importantly, between 1961–65, Lincoln made profits of $20 million, insuring there would be future models.

It took Lincoln almost 40 years to overtake Cadillac in sales, but in 1998, the process set in place by McNamara and Mills brought Lincoln back from oblivion to best Cadillac. McNamara and Mills, both retired by then, were proud of what Lincoln had accomplished, because without their efforts there would have been no Lincolns after 1960.

Photos: Ford Design

Books by Jim and Cheryl Farrell

Ford Design Department—

Concepts & Showcars

1999, 10×13, 400 pages, Fully indexed

900 photos. Includes 150+ designers and sculptors, and highlights 100 concept cars.

ISBN 0-9672428-0-0

Lincoln Design Heritage:

Zephyr to LS (1936-2000)

2021, 10×13, 480 Pages, Fully Indexed

1,600 photos and illustrations

ISBN 978-0-9672428-1-1

The Ford book is $50 plus $7 S&H (US). The Lincoln book is $85 plus $10 S&H (US). Both books bought together are $110 plus $17 S&H (US). To order, email: cfarrell57@gmail.com

I was 14 when the ’61 Lincolns and T-Birds hit the market. Coming from a GM family (Pops was Buick and Pontiac–all pre-owned, but great cars of their eras!), seeing the two Ford products ignited my interest in auto design as never before.

To my young eyes and ideals, these two designs represented a sea change in how I viewed Ford products. There was no question to me (ignorant until now of the politics involved in those design and marketing decisions) that the T-Bird, though a four-seater still, was a vast improvement over the so-called “Squarebird”, and the Lincoln? No words could describe its superiority over the oddball, angular ’58-60s, which I found unattractive, to say the least! When I think now of the capital expense to bring those ugly unibodies into existence, I’m astonished it ever passed management approval.

Though the Lincolns and T-Birds of ’61 did share some DNA, this was handled so perfectly, with details and features being shared, then swapped and modified to satisfy the market, that kudos were definitely earned by all the design staff involved in these two landmark vehicles!

I was a fanatic model car builder in those days, and purchased from a meagre allowance a sizeable quantity of AMT kits of these two cars.

Lehmann-Peterson (who I believe were the originators of the stretch Lincoln limousine) were located only two blocks from my house in Chicago back then, and although I was too shy to actually visit their premises, I did write for some information and received in the mail a press package with a kind letter from (Robert?) Peterson, and some dandy 8 X 10s of both exterior and interior of their product. WOW! was I ever smitten from that point on!

My next build was a L-P stretch made from two AMT kits, in black (of course), with a pale blue and gray two-tone broadcloth-simulated interior in the rear and black leather in the driver’s compartment. It won a number of local contests against the usual terrible flights of mid-’60s purple Metalflake fantasy that other kids were building in those days.

Later, in ’68, I owned a ’61 T-Bird. 390, auto as they all were, power everything, a/c,tilt-away steering wheel that I never tired of demonstrating to neighbours and friends, Pale blue with a blue vinyl interior and high-heel marks in the rear headliner. Hmmm… It drove and rode like a dream, but was a ridiculous gas hog for a college student’s budget.

I’ve never had an opportunity to own one of these classic Lincolns, though, I have always lusted after them. Now that I live in Italy, this will remain a dream, sadly. But a lifelong inspiration.

“Lincoln” Thunderbird was planned with front wheel drive! Missed opportunity!

Interesting report. My career, with Ford Motor Company, began in 1960 just a few months before the ‘61 Lincoln’s were introduced.

We designers, at Ford, we’re all enamored with the new design and felt it would succeed – as it did.

While I remember some of the details a bit differently, I’m somewhat astonished that no photos of the final product are included.

Photos: https://www.google.com/search?tbm=isch&q=1961%20Licoln&tbs=imgo:1

Great and insightful article.

I believe Don DeLarossa had more to do with exterior design than add ons and exterior trim.

I would enjoy hearing other designers thoughts on this.

Thanks again for enjoyable historic Lincoln journey.

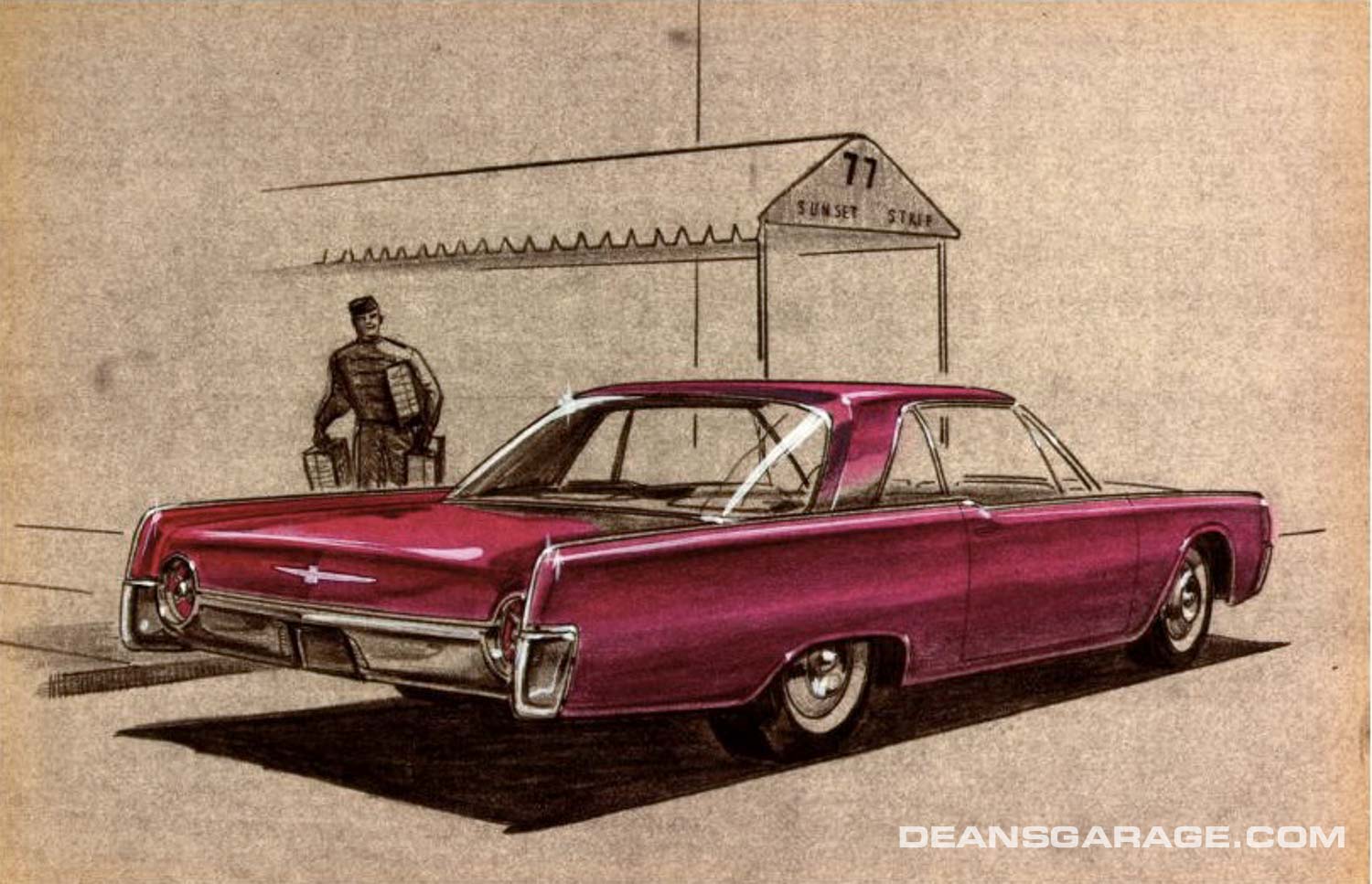

Did anyone else notice the address on the awning in the first rendering?

Yes—77 Sunset Strip—77 Sunset Strip is an American television private detective drama series created by Roy Huggins and starring Efrem Zimbalist Jr., Roger Smith, Richard Long (from 1960 to 1961) and Edd Byrnes (billed as Edward Byrnes). Each episode was one hour long when aired with commercials. The show ran from 1958 to 1964. The character of detective Stuart Bailey was first used by writer Huggins in his 1946 novel The Double Take, later adapted into the 1948 film I Love Trouble.

I, for one, instantly noticed the “77 Sunset Strip” on the awning behind the austere Lincoln with the ’62 Galaxie rear end and Thunderbird trunk badging. (Thank goodness they didn’t build that dreadful car.)

The opening credits of the series showed marvelous live-action shots of Sunliners, and later Thunderbird convertibles, turning east onto Sunset Boulevard out of the driveway to Dino’s, a ritzy steak house owned by Dean Martin. “Kookie” was always ”shoving” the cars forward by their left tail fin! The background was occasionally populated with dark-colored Mercurys, Edsels and Fairlanes.

Fortunately, a lot of these clips have been preserved on YouTube. That was The Era That Was!

My first design job after graduating from Art Center in Jan 1963 was into the Lincoln Advanced studio headed up by Buzz Grizinger and Bob Koto. If I recall correctly, there were five-six designers led by Bob Atkins, and a team of 15-20 modelers constantly working on new clay proposals. The atmosphere was somewhat frantic and daily overtime until 9:00pm was the norm. Many good looking designs were created and evaluated, almost on a daily basis. I would go home at the end of the day exhausted but jazzed because my daily output was going to be evaluated by the top brass. But alas, the next day I would learn that the concept had been rejected without explanation. So would start over again. Wall paper but no cars.

This article confirms to me what we designers suspected: Design decisions were being made by people who were not designers. None of us had any knowledge of the business challenges or decisions being made by top brass and product planners. Consequently, we never understood what they wanted.

Hello again.

I enjoyed Mr Lonbergers comments. Yes…in the early era of Design….many Design decisions were made by the least qualified upper level political corporate buerocrats.

You must realize the Design arm of the company was basically a lower echelon of the bigger picture with many levels having more input on Design than the actual Design teams. This began to change when Jack Telnack took the reins and the decision making process became more powerful. Gene Bordinat and the upper director levels like Don DeLarossa, Don Kopka, Dave Ash, Gale Halderman etc., had a more dramatic impact on Design.

However, a powerful top executive like Lee Iaccoca, having 13,000 plus Ford employees under his charge could walk in and wreak havoc on some of the Design Proposals and there was nothing anybody could do. Top down Design process. That process happened everywhere in the various big 3 or 4. Just corporate bureaucracy

And sometimes that’s just the challenge. It really does take a team to bring a new model into existence….some of it phenomenal and some not so much.

Many thanks Christopher for your thoughts and insights. I don’t really blame anyone at Ford…it was just the way they operated. They believed they were right (Whiz Kids). All I know was that after a period of time, I had enough and quit. GM hired me and I thought I had died and gone to heaven. I quickly learned that everything that came out of GM Styling was the direct result of one very powerful and bold leader (William Mitchell) and his band of the very best designers. He was the Maestro.

The 1961 design for the Lincoln Continental is clearly iconic. I would be interested in hearing from those connected to it or with other inside knowledge of the design studios at Ford in those years, how legitimate (or not) would be the claim that Wes Dahlberg’s Taunus design for Ford of Germany greatly influenced Engel and his team working on the Continental. I was surprised to see no mention of that either to confirm or refute the claim.

https://macsmotorcitygarage.com/designers-favorite-1961-lincoln-continental/

As a ten-year-old car fanatic in fall of 1960, I was blown away by the new 1961 Continentals when they were introduced. I remember thinking to myself as a 13-year-old, seeing a ’63 Continental drive by while delivering newspapers on my route, “THAT will be a timeless classic in years to come – but the ’63 Cadillac, not so much”….

Well, three things…first, I always thought McNamara was a dolt and a poltroon. Second, I really liked the ’58-’60 Lincoln Continentals. And three, it looks to me like it took two model years to get the “’61” Lincoln styling right. All just opinions here.