Design of the 1961 Lincoln, Part 1

By Jim and Cheryl Farrell

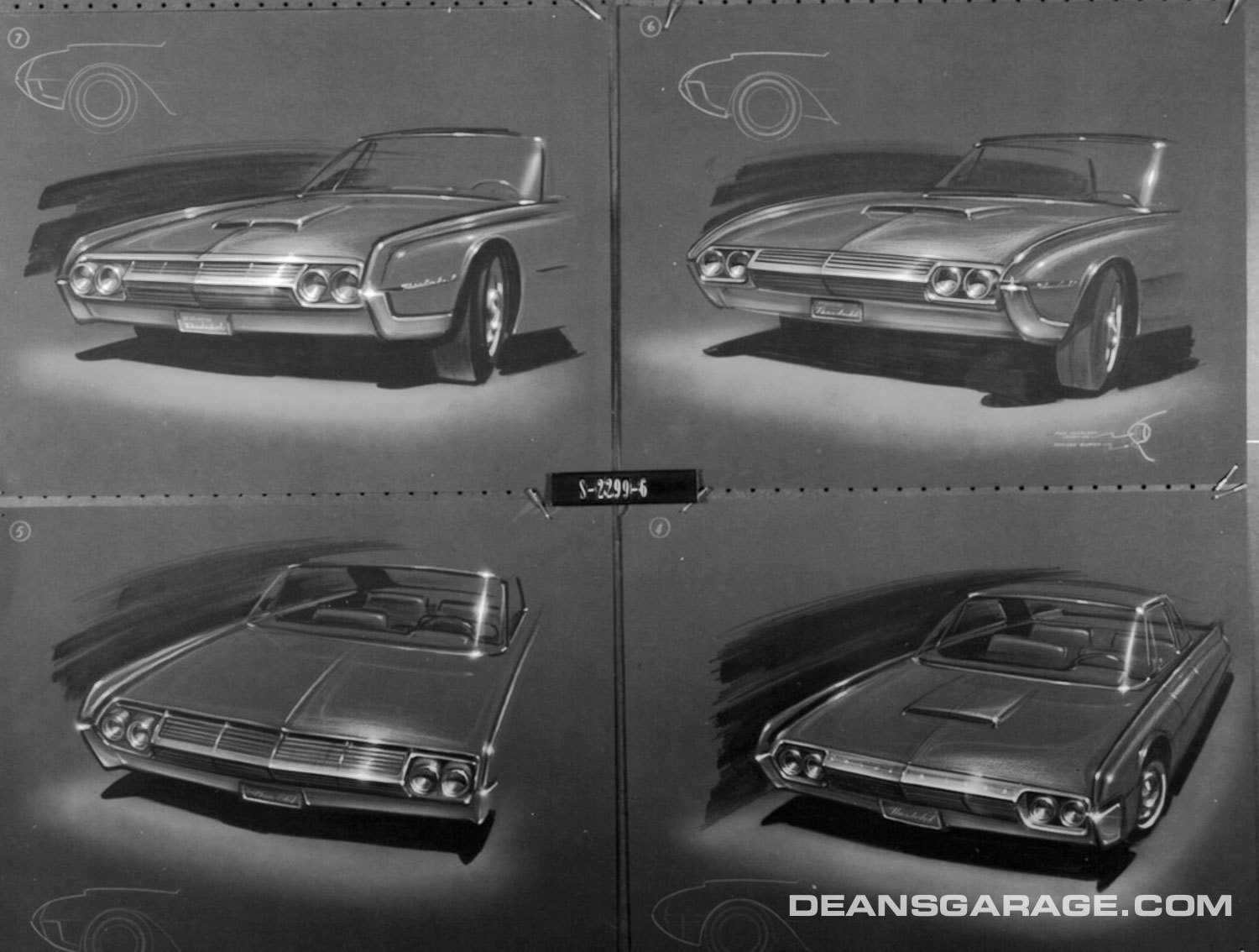

In summer 1957 design the ’61 Thunderbird began, and almost a year later Joe Oros’ Ford studio was still having trouble coming up with an acceptable design direction for the next Thunderbird. Part of the difficulty was Ford vice president Robert McNamara who couldn’t decide if the ’61 Thunderbird should be a continuation of the ’60 Thunderbird or a completely new car. Another problem was Jim Wright the new head of Ford Division who wanted a “more sporty” ’61 Thunderbird, and he thought the designs he reviewed so far weren’t headed in the that direction.

By late 1958, there were also problems at Lincoln. The Lincolns and Continentals introduced for the 1958 model year were supposed to be the cars that finally closed the sales gap with Cadillac. Instead, they were flops, and Lincoln was bleeding money and loosing market share. By December 1958 Lincoln was in jeopardy of being discontinued but Lincoln designers and engineers were generally unaware it was so bad Ford might stop producing Lincolns and Continentals.

Because the Ford studio was slow in coming up with a design direction for the ’61 Thunderbird, Elwood Engel, who was George Walker’s assistant manager, decided he wanted his own studio to design a proposal for the ’61 Thunderbird. He and Walker thought if Engel designed the new Thunderbird it might cancel out his work on the ’58 Lincoln and increase Engel’s chance to succeed Walker when Walker retired in three years.

Engel got his new studio. It was located in a small room in the basement of the Styling Center, and it was called the Corporate Advanced studio. Engel hand-picked the designers for his new studio. Those who worked on Engel’s ’61Thunderbird proposal included John Najjar (exec), Gale Halderman (manager), designers Colin Neale, John Orfe, and design analyst Bob Thomas. Designers Phil Payne and Dick Avery were later assigned to Engel’s studio as the car was nearing completion. Harry Strickler was the lead clay modeler. Engel and his designers immediately began designing their preposed Thunderbird.

Even though the 1956–57 Continental Mark II had been discontinued only the year before, by 1958 it was increasingly being referred to as a classic. Engel had been one of the primary designers of the ’58 Lincoln and, in a strange way, its rejection made the Mark II more appealing, therefore he used it as the benchmark for the Thunderbird proposal his studio was designing. In contrast to the ’58 Lincoln they had earlier designed, Engel and Najjar agreed that their alternate Thunderbird proposal had to be clean with no garbage on it. Engel told his designers that he wanted their Thunderbird proposal to be similar in design to the Continental Mark II—but “taken to the extreme.”

Designers in Engel’s studio actually completed two full-sized clay model ’61 Thunderbird proposals, and they were ready by late June 1958 as was the Ford studio’s proposal. At Engel’s suggestion, the belt lines on both proposals were capped by a narrow bright metal cap. Engel told designer John Orfe he got the idea of the bright metal cap at the top of the belt line from the Quicksilver concept car, which had been completed several months earlier in Jim Darden’s Ford Preproduction studio. Except that the overall design loosely followed the Mark II, the rest of the car’s design was fresh—except for the big round Ford taillights.

When it came time to choose the new Thunderbird, Engel showed his more conservative proposal to the Product Planning Committee. Before the meeting, Walker asked Oros to support Engel’s proposal over the one designed in his (Oros) studio. Oros knew Walker wanted Engel to replace him when he retired in three years and was doing what he could to encourage Engel’s promotion. Oros supported Walker’s efforts, but he told him he couldn’t support Engel’s Thunderbird proposal because he honestly believed the Ford studio proposal was the better of the two. Under pressure from Walker, Oros told him the best he could do was remain silent.

The Product Planning Committee meeting to choose the ’61 Thunderbird design was held in late July 1958. Walker argued persuasively for Engel’s proposal. Jim Wright, head of Ford Division, urged that the Ford studio proposal should be the next Thunderbird. At one point, having heard nothing from Oros, Henry Ford II pinned Oros down and told him he wanted his candid opinion. Oros acknowledged that the formal look of Engel’s proposal would look fine as a Lincoln, but he favored the Ford studio proposal because it continued Thunderbird’s sporty look. Henry agreed, a vote was taken and Engel’s rejected Thunderbird proposal went back to his studio on the freight elevator. The Ford studio Thunderbird proposal had been chosen.

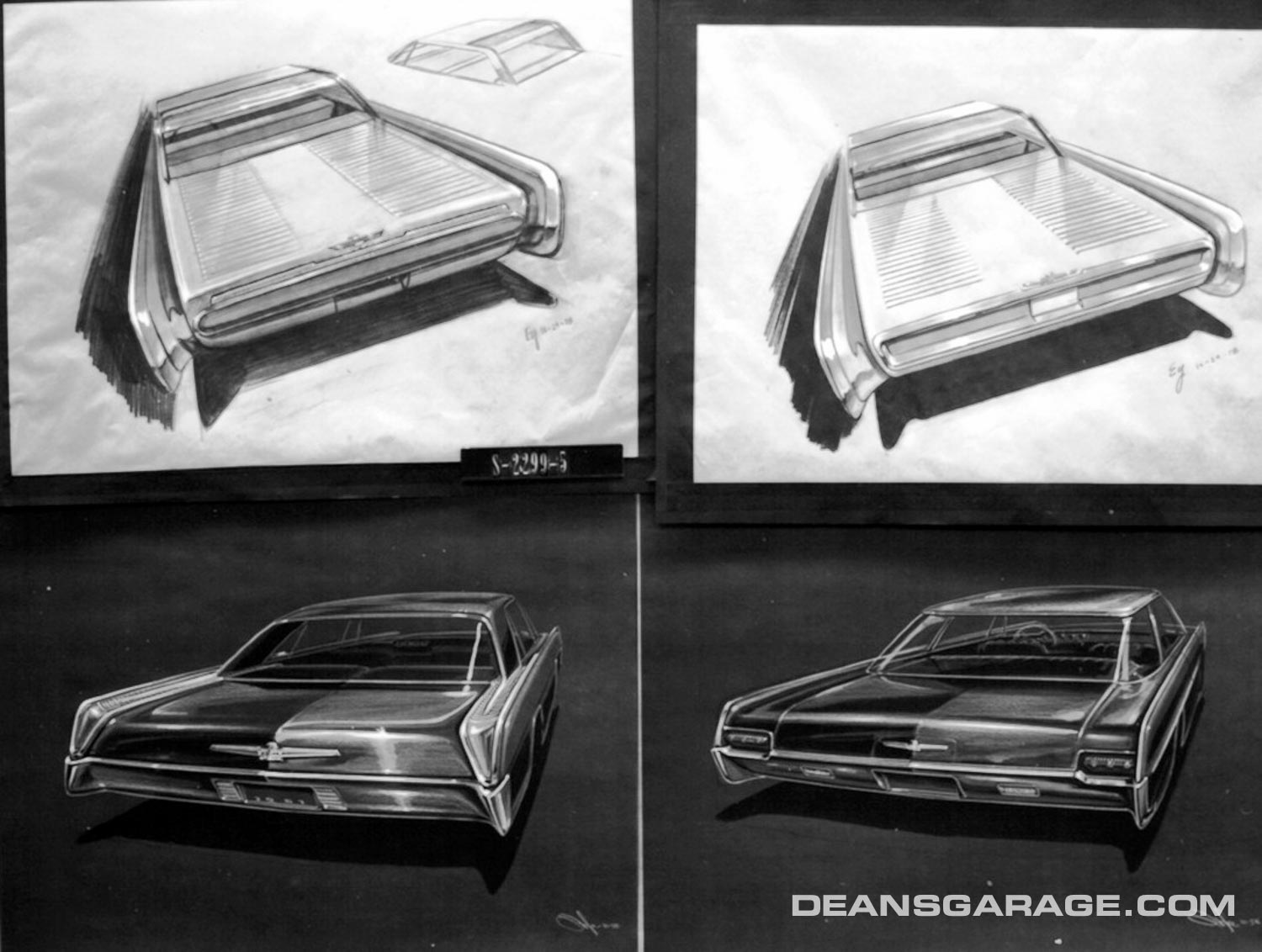

Although Ben Mills, head of Lincoln Division, voted for Engel’s design as the next Thunderbird, when Oros’ proposal won, he immediately told Engel he wanted his Thunderbird proposal as the next Lincoln. Engel was encouraged, and when he got back to his studio, he instructed his designers to replace the big round Ford taillights on the clay model with large chrome caps on the ends of the rear fender blades, to design a squashed horizontal tube in the area between the blades, and to include a separate grille at the back of the deck lid inside the squashed tube. Then they waited.

Robert McNamara, Ford’s vice president in charge of all vehicle production, missed the meeting at which the Ford studio Thunderbird proposal was selected by the remaining members of the Product Planning Committee. Neither Mills nor McNamara recalled what they talked about before McNamara went the Styling Center, but within the next week, Walker took him to the different design studios to review the selections made by the other members of the Product Planning Committee. When they got to Engel’s studio, the rear end of the his Thunderbird proposal had already been restyled to incorporate capped blades and a rear grille nacelle. McNamara looked at the proposal for several minutes and then started asking Walker and Engel questions about it. One of the questions he asked was whether it could be made into a four-door Lincoln. Walker said it could, and Engel told McNamara it would take about two weeks to turn the model into a four-door Lincoln. McNamara then left.

Because he had previously been head of Ford Division, McNamara was familiar with their future plans, but he didn’t know much about Lincoln’s future plans. So he set up a series of biweekly meetings with Lincoln’s management and engineers to find out exactly what their plans were. Those meetings were held in a conference room at the Styling Center, and were attended by Mills, Harold McDonald, Lincoln’s chief engineer, Emmett Judge, Lincoln’s chief product planner, and support staff including Harold Johnson, who was Lincoln’s Executive Engineer Advanced. No one from Styling Center was invited or took part in McNamara’s bi-weekly meeting, probably because McNamara had already decided the design he wanted for the next Lincoln.

Routine presentations were made during the first two of McNamara’s meetings. By the time of the third and fourth meetings, they had become presentations with little discussion, except when McNamara asked questions. During the fourth meeting, that all changed. McNamara stopped whoever was making the presentation, and said it was time to “clear the deck and put all the cards on the table.” Everyone except Mills, McDonald and Johnson were asked to leave the room, and then McNamara announced that, based on Lincoln’s dismal financial projections, he had decided to recommend the Lincoln car line be terminated. McNamara didn’t like the direction Lincoln was heading, didn’t like the fact Lincoln had never made a profit, and he hadn’t heard anything from Lincoln’s management that had so far changed his mind. Ben Mills then asked, “Bob, you can’t really do that, can you?” McNamara answered, “You bet I can do it.” Then a very heated discussion took place with everyone in the room arguing against McNamara’s proposed recommendation, but McNamara gave no sign of changing his mind. After what seemed like an eternity of back and forth argument, McNamara finally told Mills that, with great reluctance, he would agree to one more Lincoln production cycle, but only on the conditions the next Lincoln be a lot smaller, a 4-door made from the 2-door Thunderbird proposal he had recently seen in Engel’s studio, and that Lincoln finally make a profit.

Photos: Ford Design

Books by Jim and Cheryl Farrell

Ford Design Department—

Concepts & Showcars

1999, 10×13, 400 pages, Fully indexed

900 photos. Includes 150+ designers and sculptors, and highlights 100 concept cars.

ISBN 0-9672428-0-0

Lincoln Design Heritage:

Zephyr to LS (1936-2000)

2021, 10×13, 480 Pages, Fully Indexed

1,600 photos and illustrations

ISBN 978-0-9672428-1-1

The Ford book is $50 plus $7 S&H (US). The Lincoln book is $85 plus $10 S&H (US). Both books bought together are $110 plus $17 S&H (US). To order, email: cfarrell57@gmail.com

When I was a pre-teen, the wreckage of the Reith plan of the Edsel, the super Mercury and the bloated 1958 Lincoln’s cost Johnson County, Indiana (the county south of Indianapolis) its Edsel-Mercury-Lincoln dealer. To buy a Mercury, Comet or Lincoln in 1961, you had to buy one in Indianapolis, Shelbyville or Columbus. My first real view of the 1961 Lincoln Continental was the AMT annual kit. Of all the Lincolns ever made, even the Mark II, the Engelbird, finalized for production in 1960, is still the most impressive U.S. luxury car design in my eyes and mind. One has to credit Ben Mills and Robert McNamara for allowing the Lincoln brand to live. It had to influence G.M.’s Bill Mitchell to evolve Cadillac’s styling in the mid-1960s. Obviously with Engel at Chrysler by 1962, the influence of the 1961 Lincoln on the 1964 (and later) Imperials is undeniable. I wonder what Henry Ford II thought of his 1961 Lincolns ? He must have approved as it set the template for the Lincoln sedans until his passing. Thank you for sharing the detailed account of how this great car came to fruition.

I think I’ve opined here previously that Lincoln traditionally built only two different automobiles, either extremely ugly or exquisitely beautiful. In my mind, Ford’s # 1 most embarrassing blunder was the blasphemous 1957 facelift that insulted the most beautiful Lincoln of all time, the 1956 Premiere. All those years Lincoln designers spent trying to build a car that would out-sell Cadillac, only to free-fall into a vat of manure, by adding ugly fins and water-buffalo headlamps to the marvelous 195X Continental dream car.

I’ve often daydreamed what would have been the final outcome if the 1957 Thunderbird had evolved and remained a luxury/sports car, the same as Corvette. And if it had, the ’58 Thunderbird had been released as the Edsel, instead of suffering through its various identity crises before dying an unloved stepchild.

As much as I couldn’t stand the 1958-1960 ‘Chinese outhouse’ Lincolns, had I known back then Henry was planning to make them drive the plank, I would have screamed bloody murder! It was tough enough living through the loss of Edsel and then De Soto.

If you’re a Lincoln fan, keep an eye on the marque. Notice that Ford isn’t doing much to promote the brand, the same as they did Mercury before pulling the lifeline plug. Notice, too, how their recent marketing strategies are distancing the Lincoln brand from Ford Motor Company.

One thread here stands out for me: I didn’t need any more reasons to dislike Robert McNamara, and every time I read another article here I get one anyway.

Oh, and just to contribute here, I really really liked the ’58-’60 Lincoln Continentals. Especially the ’60 convertible.

Nice article.

Do you have something about GM front wheel drive cars 1930s to 1940s?

Or something about the 1961 Thunderbird FWD prototype?

Or the Imperial FWD A-615 prototype?