Six of GM’s “Damsels of Design” who worked on automotive interiors, photographed circa 1955. From left: Suzanne Vanderbilt, Ruth Glennie, Marjorie Ford Pohlman, Harley Earl, Jeanette Linder, Sandra Longyear and Peggy Sauer. All images courtesy General Motors Design Archive & Special Collections.

The Story Behind GM’s Celebrated ‘Damsels of Design’

The first prominent all-female design team in American history

By Rebecca Veit. Reprinting permission requested.

Spend any time researching pioneering female designers and you’ll likely run across General Motors’ so-called Damsels of Design, a group of ten women brought on board by the automaker in the mid-1950s, and the first prominent all-female design team in American history. But not a lot of people know the full story of the Damsels, which is not quite the tale of female empowerment you would hope for.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the Damsels’ history begins with a man. Harley J. Earl was the vice president of GM’s Styling Section (now known as GM Design), where he ushered in a number of new design strategies for the automaker, including concept cars, planned obsolescence and the notion of stoking consumer demand with annual model updates. He also introduced female designers to his department in the ’40s and ’50s, believing they could help make automobiles that appealed to female consumers. As he put it in a 1958 press release, “The skilled feminine hands helping to shape our cars of tomorrow are worthy representatives of American women, who today cast the final vote in the purchase of three out of four automobiles.”

Early hires in the Styling department included Helene Rother, who joined GM in 1943 (staying for four years before setting out to establish her own design firm that specialized in automotive interiors for Nash Motors) and Amy Stanley in 1945 (of whom very little is known). But, according to GM archivist Natalie Morath, the automaker kept news of its first female designers under wraps. Then, in the mid-1950s, Earl set out to enlist more women and recruited heavily from Pratt Institute’s industrial design program—and this time, the new hires were widely publicized and used as a marketing tool. The ten who joined GM were quickly dubbed the “Damsels of Design” by the automaker’s PR team.

Their ranks included Suzanne Vanderbilt, Ruth Glennie, Marjorie Ford Pohlman, Jeanette Linder, Sandra Longyear and Peggy Sauer—whom were placed in GM’s automotive interior-design departments for brands like Chevrolet, Buick, Cadillac, Oldsmobile and Pontiac. There they worked on every interior element (seats, doors, trim, detailing, color and fabrics) except the instrument panel, which was deemed off limits to women. The other four Damsels—Jan Krebs, Dagmar Arnold, Gere Kavanaugh and Jayne Van Alstyne—worked as industrial designers for GM-owned Frigidaire, where they helped create the Kitchen of Tomorrow, and also designed displays and exhibits for the Styling department.

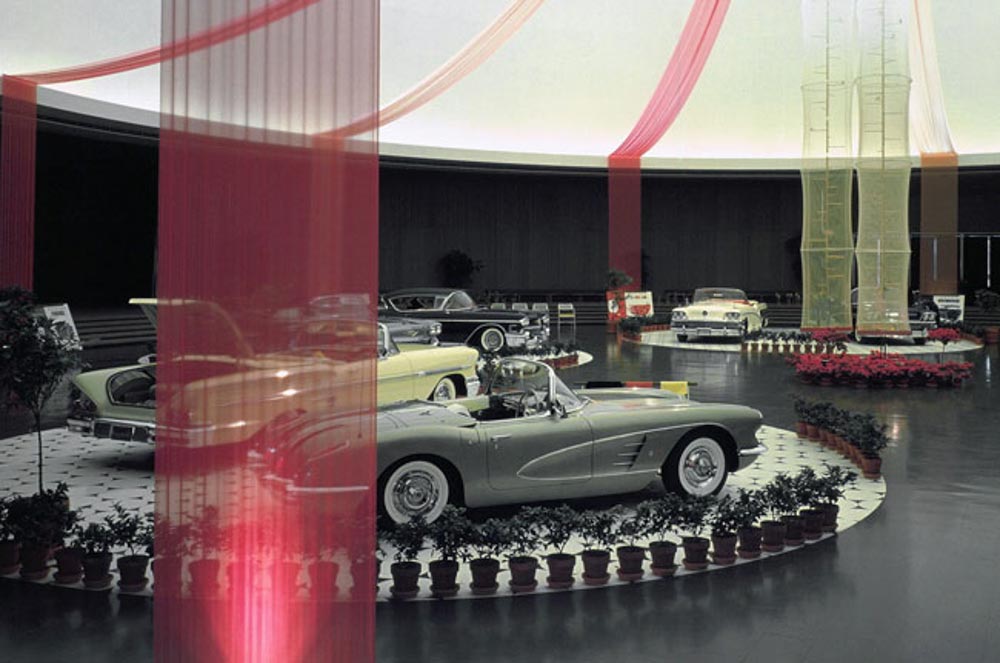

In 1958, to promote the Damsels’ work, Earl organized what was called the Feminine Auto Show in GM’s Styling Dome. The women embraced the design challenge, and as designer Suzanne Vanderbilt put it, “particularly enjoyed proving to our male counterparts that we are not in the business to add lace doilies to seat backs or rhinestones to the carpets, but to make the automobile just as usable and attractive to both men and women as we possibly can.” As Jeff Stork pointed out last year in Automobile magazine, this included adding features that we now take for granted like child-proof doors, lighted makeup mirrors, retractable seat belts and storage consoles.

Of course, it’s easy now to roll your eyes at the promotional video for the exhibition and dismiss it as a throwback to a time when inequality reigned and women were supposedly only concerned with snagging their nylons on the seat upholstery. But as Vanderbilt relates, the ingrained sexism directed at the designers was a real impediment to their careers, and a constant thorn in their sides: “What distressed most of us was that we could never be identified as just designers. We were always ‘la femmes’, or ‘the female designers’, … but as designer[s], we designed the same as the men did.”

Unfortunately, the Damsels’ tenure at GM only lasted a few years, coming to an abrupt end when Earl retired after the 1958 exhibition. His successor, Bill Mitchell, was less than enthusiastic about working with female designers, and most of the women scattered to other jobs in design. Most notably, Dagmar Arnold went to IBM, where she was the first woman at the company to receive a patent, for her external design of the 1301 Disk Storage Unit. Suzanne Vanderbilt and Jayne Van Alstyne both stayed on at GM—for 23 and 14 years, respectively—and continued to challenge the male-dominated field.

Glennie’s Fancy Free Corvette for the 1958 Feminine Auto Show—an exhibition staged to promote the female designers’ work.

Glennie’s Corvette came with a set of four interchangeable seat covers (one for each season), as well as GM’s first ever retractable seat belt.

Glennie with the Fancy Free Corvette, 1958.

Sauer redesigned an Oldsmobile Fiesta Carousel station wagon for the 1958 exhibition.

The Carousel’s child-friendly backseat included storage for toys, a magnetic game board and child-proof latches that could be controlled from the dashboard.

Gere Kavanaugh transformed GM’s Styling Dome for the 1958 exhibition, which included ninety rented canaries housed in floor-to-ceiling net columns. (When the lights were switched on, the birds would start singing.)

“The fairer sex of America strikes again!”

Vanderbilt demonstrating an early car phone and built-in memo pad—custom features for her 1958 exhibition-model Cadillac Eldorado Seville.

Linder loading a matching set of luggage into the trunk of her exhibition-model Impala Martinique.

Longyear’s exhibition-model Bonneville Polaris convertible for Pontiac featured a storage compartment for a picnic.

Pohlman demonstrates the glove box dictaphone included in the exhibition-model of her Buick Shalimar.

The purple interior included a hidden umbrella compartment and a somewhat absurd overhead light fixture.

Pohlman with her exhibition-model Tampico Buick Special convertible.

Wow, what a revelation! Virtually every car in the “dream car” section has perfectly good ideas included, many of which we are just getting back to (child-friendly interiors, picnic carrying interiors, etc). The there’s the changeable interior colors, what a great idea! Color-matched luggage. An umbrella that’s in the car and not in the trunk or on the floor. Child door locks. And isn’t the Fancy Free Corvette painted Fawn Gold?

But my real question is, are any of the specials shown still in existence? I’d love to have the Olds wagon and the Corvette!

Thanks for posting, this team had some really nice ideas some only implemented many years later.

This program first started in 1957 with these ladies. Photos of their creations that year are very scarce. I have photos of Peggy Sauer’s `57 Olds 98 “Mona Lisa” pearl orange hardtop, and her lavender 98 convertible.