The Golden Years of GM Styling: A personal recollection of William Mitchell, Vice President of General Motors Styling

by Roy Lonberger

Heritage Center Interview

In April 2011 Roy Lonberger was invited by John Manoogian (former Head of Cadillac Exterior Design) to visit the GM Heritage Center and GM Design. During that visit Susan Skarsgard (Global Industrial Design Manager) and Christo Datini (Chief Archivist, GM Design Archives) interviewed Mr. Lonberger regarding his brief career as a designer from 1965 through 1968 during the golden years of GM Design under William Mitchell, GM Design’s Vice President. The following are paraphrased excerpts from that interview.

John Manoogian: Tell me about your brief career at GM Styling and your personal involvement with William Mitchell, Vice President.

Roy Lonberger: Thanks John. I am happy and honored to describe my version of what it was like to work for Mr. Mitchell. Hard to believe that it has been forty-four years since leaving GM, so I cannot vouch for the detail accuracy of my recollections, but will do my best.

Allow me a moment to preface my remarks by saying that automobile design at GM Styling in the 1960s was a team sport. Every designer likes to say that he designed this car or that car. But the truth is that none of the remarkable GM cars could have been realized without the rare convergence and group effort of a small group of talented, passionate, and sometimes stubborn car people—the power players that worked with (and occasionally worked against) one another to achieve their own objectives and realities. Whether from the individual designer who drew the first line of inspiration, to the team of designers and model makers who refined the details, to the engineering group that got things functional, to the executive in charge that defied Board Management and made things happen. Without reservation in my mind, none of the high profile cars we consider today as milestones in automobile design could have seen the light of day if it was not for William Mitchell, then VP Styling.

For anyone (particularly my students) to be interested in my comments, one must first understand the context of events and players within GM Styling during that period.

The Usual Suspects

RL: First, GM Styling was riding on the fame and legacy of Harley Earl, the glamor of the Motorama show cars, the flamboyancy of VP William Mitchell, and the performance cars of Larry Shinoda.

Second, GM enjoyed world domination of the automobile marketplace with over 63% (Chevrolet alone surpassed every other brand with over 35%).

Third, because of the market share, GM had experienced antitrust suits from the government and were being threatened to divest one or more of its divisions (Chevrolet).

Fourth, in defense of (and perhaps preparation for) probable government action, Styling was virtually walled into two operations: Chevrolet and everyone else. Each had management teams that led directly to Mr. Mitchell, but not with each other. Chevrolet Styling enjoyed direct interaction with the Chevrolet Engineering groups (including the famous and secret Chevy R&D team led by Frank Winchell).

Fifth, all of the studio doors were locked with electronic pass cards. Designers were not allowed to travel from one studio to another without an escort.

Sixth, GM was prohibited by GM Executive management to engage in any racing activities, for fear that racing success would increase sales and further attract the eyes of the government antitrust politicians.

Seventh, an eager lawyer Ralph Nader wrote a book called Unsafe At Any Speed which attacked the safety of the Corvair, said book singlehandedly destroying the viability of the Corvair in the marketplace. Though his charges were later refuted, top GM Executive Management made the mistake of using illegal investigation techniques on Nader, and later were admitted before Congress (further increasing the attention of the antitrust types in government).

Eighth, the emergence of high technology and computer efficiency was offering new and better ways of doing things, threatening some management who would not/could not adapt to change.

Ninth, Ford had introduced the Mustang. GM countered with the muscle car. Chrysler officially went racing. Ford officially went racing, wanted to buy Ferrari, but instead won at LeMans in the GT-40. GM Executive management prohibited racing. As a result, the clandestine Chevy Engineering R&D group was created by Bunky Knudsen and led by Frank Winchell to provide engineering support to racers including Chaparral’s Jim Hall and Hap Sharp, Roger Penske and Mark Donahue, and A.J. Foyt.

Tenth, social and political unrest had surfaced during the 1960s: Bay of Pigs fiasco, threat of World War III with Russia over the Cuban missile crisis, an illegal war in Vietnam, antiwar movement, flower child hippie generation, civil rights movements, political assassinations, race riots in Detroit and elsewhere, government mandated safety programs, and culminating in a presidential impeachment several years later. Even a moon landing. Anti-materialism. Declining interest in cars. The Age of Aquarius. The times they were a changing (to paraphrase Bob Dylan).

Last, car enthusiast Bunkie Knudsen, (Board Member, VP of Overseas Operations, former General Manager of Chevrolet responsible for the muscle cars, and former head of Pontiac responsible for the first GTO and in line to become GM president) was side stepped in favor of Ed Cole (the dynamic engineer who was responsible for the small block Chevrolet V-8). Long a supporter of performance cars, instrumental in creating the secret Chevy R&D with Frank Winchell, and a personal friend/supporter of Mr. Mitchell, Bunkie Knudsen was later to leave GM and become President of Ford, with Larry Shinoda to follow.

At GM, everyone seemed to be walking on pins and needles: Afraid to take a position, do anything bold, preferring to remain hidden and out of sight.

And yet, in this atmosphere of change, pending gloom, and conflicting loyalties of separate management teams and inside political battles between the car guys and the bean counters, Mr. Mitchell was able to excite his design team, sidestep the cautious executive management, and produce some of the world’s most exciting cars.

GM Styling in those days did not resemble anything currently being done at GM Global Design today. In fact, it was so different than today it is hard to believe it ever existed.

As a former GM designer, now business man, and currently student mentor, I hope that the following illuminates the amazing force of this one man, explains how design was practiced in that period, and provides insight to my students about the world of automobile design. More importantly, how one man with a vision can make a difference.

JM: On your first day at GM, were you assigned to a particular production studio or were you asked where you wanted to work?

RL: Actually neither. Like all new designers, I was assigned to the Orientation Studio led by Robert Verizer. Mr. Mitchell felt that all new designers needed to learn the way cars were designed at GM, so they could be evaluated for which studio they should later be assigned, or whether to continue their employment at all. Most designers spent 9–12 months in this studio. I concentrated on Corvette and Corvair performance vehicles.

JM: How long were you in the Orientation Studio and where did you go after that?

RL:: Three months later I was assigned to Studio-X in the basement to work for Mr. Mitchell and Robert Larson (then Head of Studio-X). Larry Shinoda (who was executive assistant special projects to Mr. Mitchell) would come into the studio from time to time to direct activities. With both Larry and myself being former designers from Ford and LA hot rod enthusiasts, we immediately developed a friendship.

JM: How unusual that you were directly assigned to Mitchell’s personal and famous Studio-X. How many other designers were there in Studio-X?

RL: None. Just myself. Chester Angeloni was the chief model maker, along with two other model makers and a tech-stylist who prepared the full size lofting drawings for engineering.

JM: You were the only designer? What cars did you work on?

RL: The first car was the three wheeler now called the Astro III (XP-800). It had been an ongoing project for a year, but did not have the aircraft look that Mr. Mitchell wanted. So we turned it from a three lump collection of elliptical forms into an aircraft look inspired by the supersonic transport. Why it is called the Astro III is puzzling, because it was created a year and a half before the Astro I (XP-842).

The second car was the Toronado XX (XP-866) which was based on the first generation Toronado designed by David North. Mr. Mitchell wanted to create a personal version for himself with a shortened wheelbase, extended front fenders, and a lowered fast back roof. The most unusual feature of the design was a backlight that was tinted with the same color as the dark body paint, the net result being a super smooth fastback without any visual interruptions for window cutouts. Mitchell loved this concept.

After three months, I was assigned upstairs to Chevy-2 Performance Studio (headed by Hank Haga).

JM: Before we talk about Chevy-2, tell me how it was working with Mr. Mitchell in Studio-X?

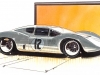

RL: Like working with God. You have to understand that I wanted to be a car designer working for GM ever since I saw the LeSabre show car at the Motorama show when I was twelve years of age. When the Stingray Racer, the ’63 Corvette, and Monza GT/SS were created, I thought they were the best cars ever designed. I regarded Mr. Mitchell, Larry Shinoda, and Chuck Jordan as design icons even before leaving school. And I had a chance to work with these giants on a day to day basis in the most special and famous of studios.

Mr. Mitchell had the passion and flamboyant style, Shinoda had the personal no-nonsense Southern California performance connection, and Jordan had the elegance and taste—anything they touched was destined to be a success.

JM: Again, how was it working with Mr. Mitchell?

RL: Sorry about that. The truth of the matter is that one never worked with Mr. Mitchell. Rather you worked for him. And you were always aware of that fact. He was not the buddy type nor the unemotional business school MBA type. He was outrageous in his passion for cars. And he suffered fools rarely. In his eyes, either you loved cars (his cars) or you were not tolerated by him. And he spared no bones about how he felt about you or your design. Please him and you were his designer, but fail him and you were assigned to the truck studio. Or worse, across the invisible wall into the BOP studios.

He wasn’t the easiest person to work for. He was demanding, opinionated, and sometimes vulgar. But I respected his passion and honesty. You always knew what he thought of you and your work. And he always motivated and demanded your best work.

JM: Tell me your first impression when you went upstairs to Chevy-2.

RL: My first impression was of extreme satisfaction because I was assigned to the studio that was designing performance cars.

My second impression, which was obvious immediately and reinforced daily, was the depth of talent of the other designers. I have never seen a team of designers who loved their work more, loved cars as much, and had the unequaled design and illustration talent.

And I was impressed with Hank Haga, because he was always encouraging his designers to take chances.

I was in awe, humbled, and often insecure.

Roy’s Illustrations

JM: Tell me about the cars, the designers, and the chain of command.

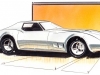

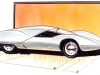

RL: The cars included all production Corvettes, many mid-engine Corvettes, Camaros/Firebirds, Corvairs, Nova SS coupe, many show cars, and non-GM customer show and race cars.

The design team usually consisted of five designers and varied over several years: Graham Bell, Jim Bisignano, Jerry Brochstein, Dave Clark, Jim Ferrin, Ira Gilford, Dave McDonald, Dave McIntosh, David Stollery, and Dean Swanson. Down the hall was David North, John Schinella, Terry Henline, Bill Porter, Allan Young, and George Camp. Very talented guys.

Additionally, there were two tech-stylists (the technical people who created the engineering drawings) and a team of 5–10 model makers.

Hank Haga was Studio Head, and reported directly to Jordan, who reported to Mr. Mitchell. Later, Rybicki was interjected between Haga and Jordan. And of course, Shinoda had the run of the studio as well. All design approvals were made by Mr. Mitchell. Period.

JM: Tell me about your work routine.

RL: Remember, this was a time before computers. A typical routine for a new car would consist of the entire design team creating concept illustrations (usually 24 x 60-inches) and hanging them on the wall above the tech boards. Sketches would go up on Monday. The best concepts were modeled on Tuesday as full size tape and/or airbrush drawings. Wednesday morning, Mr. Mitchell and Chuck Jordan (sometimes accompanied by Larry Shinoda) would review everything they could see in the studio, and select a direction to be modeled. The model makers would spend Wednesday and Thursday doing the model, while the designers would concentrate on creating detail concepts and actually making mockups of the details (lights, grills, etc). On Friday, it was show time in the courtyard or inside the dome. After lunch, Mr. Mitchell and fellow executives would review the model. Criticisms were expressed, directions were selected, and orders were given for continuation (or rejection) of the project the following Monday. This routine would go on for about eight months, until a final direction was approved. At which time, the designers would finish all of the detail stuff, while the tech-stylists would make the final engineering lofting drawings.

JM: What was your first project in Chevy-2?

RL: The studio had been working on a replacement for the Stingray C-2 Corvette, scheduled to be introduced as the 1967 Corvette Mako Shark C-3. I worked on details to help finish the project.

JM: I do not remember that car. What happened to it?

RL: The running prototype was shown to the new GM President James Roche at the Milford Proving grounds. The conservative Roche and passionate Mr. Mitchell had a history of personal disagreements, so when Roche saw the car, he went ballistic in front of the crowd and screamed at the top of his voice that it looked like a race car, that GM was not interested in racing, and that he would never let his daughter drive a car like that. Just like that, the project was cancelled. Mr. Mitchell was humiliated. The only time I ever saw him turn red with outrage and not say a word.

JM: And then what happened?

RL: Two things. First, he, Larry Shinoda, and Hank Haga (and design team) did a crash program to soften the lines of the car and add a new backlight. That effort became the 1968 Corvette C-3.

Second, while yet unconfirmed, I think he got even with Roche, by converting the Mako Shark II into the Manta Ray show car (with all of the cancelled Corvette Styling), just so he could drive it in public.

JM: Back to the studio, were the clay models done in scale?

RL: No. Everything was done full scale and often several cars at any given time. I personally believe that the design successes were the result of working directly in full scale. The only time a scale model was built was during a design contest among all designers which led to an article in the Detroit Free Press magazine.

Detroit Free Press Slideshow

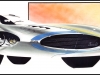

JM: That was before my time, but I remember seeing the magazine. In fact, I still have a copy of it. Had a pearl gold painted car on the cover.

RL: Yes, that was my design. Actually was intended to be a future concept for a Toronado.

Interesting story about Mr. Mitchell and this car. I wanted to explore new directions for the design with a focus on the elimination of dated and busy styling features, and instead the creation of a new smooth body shape. After exploring 20–30 concepts, Mr. Mitchell came into the studio, looked at my sketches, and then told me “they looked like crap because none of them looked liked a car that GM would ever build. Moreover, that if I wanted to continue to be employed by GM, I had better learn to design GM looking cars.” That is when I learned what the term “GM Idiom” meant.

So I discussed this with my boss Hank Haga, who gave me the second most important advice about design at GM: “Design is not about creating bars of soap. Anyone can create boring cars. Your job is to add the sizzle to the steak. If it is not original or unique, then it will not be memorable.”

So 75% into the program, I started over and made a GM car. Intended it to be a fully smooth Toronado with an obvious masculine performance flair. When Mr. Mitchell saw the finished model, he was very pleased, selected it as the winner of the competition, and put it on the cover of the magazine. He even asked me to work with Neil Madler to photograph the model for the cover.

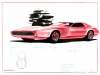

Sketches Slideshow

JM: Back to Chevy-2 studio. Tell me about the type of sketches you would do. I see the finished renderings, but did you also do rough thumbnail sketches?

RL: It was hard for me to understand at the time, but no one did rough thumbnails. Rather, every sketch was a finished illustration, usually the 24 x 60-inch size, but sometimes 19 x 24-inch. We did not call them renderings, because that was something one would do with watercolor. Rather, these sketches were very descriptive, made with marker and chalk, and very finished. And they were cranked out at the rate of one every hour or so. The level of illustration skill in that studio was mind boggling. So I asked why everyone did such finished sketches, and learned the next piece of GM design advice from Chuck Jordan: “Never explain design. If it is not on the wall for me to see, you do not have anything to say. It better be the best on the wall or I won’t see it.”

Notes:

1. Illustrations and text are used with the permission, and remain the property of Roy Lonberger and are copyright 2012 to MagnaDesign. They may not to be used in any manner without consent by Roy Lonberger and/or Magna Design. Interested parties can contact: Roy Lonberger, CEO Magna Design. RVL@Magna-Design.com

2. Photographs are used with the permission, and remain the property, of General Motors. They may not be used in any manner without consent of General Motors. Interested parties may contact the following: SusanSkarsgard, Global Industrial Design Manager, GM Design, susan.skarsgard@gm.com; Christo Datini, Lead Archivist, GM Heritage Center & Media Archives, christo.datini@gm.com.

3. Roy Lonberger was born in Southern California in 1940. His education included mechanical engineering (University of California), Industrial Design (Art Center), Graduate Business School (Santa Clara University), Graduate Ergonomics (Stanford), and Advanced Management (Kepnor-Tregoe Institute). In 1963, he graduated with Honors from Art Center (on a Ford Scholarship) at the age of 22 with job offers from Ford, GM, and Chrysler.

He began his career at Ford. leaving a year later to satisfy his military obligation. He later worked as a product designer for Tony Carsello in Beverley Hills, followed as an ergonomic engineer at North American Rockwell for the Apollo Moon vehicle. He returned to the automobile industry in January 1965 to work for GM. Three years later he left GM.

Subsequent employment included stints as a product designer at Keck-Craig Engineering, Partner & VP at George Perkins Industrial Design, Manager of Design at Memorex, Account Manager of Design at FMC, Manager of Design at FMC Europe, and Director of Corporate Identity at FMC Corporate-Chicago.

In 1976, he formed Roy Lonberger/Associates in Silicon Valley, and subsequently incorporated as Magna Design Corporation. His business specialized in non-consumer products including transportation systems; race cars; material handling vehicles; aircraft; sail boats; agriculture equipment; medical products; scientific instruments; cranes and excavators; and business products. During that period, he found time to teach design at San Jose State University and to serve as the Northern California Chairman of IDSA. Through Magna Design, he has done complete projects (industrial design, engineering, prototype development, and limited production) for over 1000 projects for 286 clients through out the world. He holds five patents and 56 design awards. He recently retired from Magna.

Currently, he is involved with several startup companies (including one that is investigating external propulsion systems for vehicles). He is also involved as CFO and Board member to a motorsports company. Most of his spare time is spent mentoring car design students, participating in various car club events, and researching automobile design history. His passion remains cars. He and his wife Carol live in Los Gatos, California.

4. I would like to personally thank John Manoogian, Jim Musser, John Schinella, John Mellberg, Gary Smith, Christo Datini at the GM Heritage Center, and Susan Skarsgard at GM Design for their support and information, and Shane Baxley for his tremendous talents in helping prepare this article. Comments, criticisms, and corrections would be appreciated.

Roy Lonberger, RVL@magna-design.com

Great interview, John! …and, “HELLO, Roy!”

Seeing this was indeed a surprise and it brought a smile as you (my former ACCD classmate) interviewed Roy, the man who, without a doubt, was one of greatest sources of inspiration, in my career.

Roy was my first “boss” in 1971 when I interned at Memorex Corporation, while a student at San Jose State University. To this day, that internship was the most incredible learning experience …and Roy is the man who inspired me to attend Art Center.

It’s great to hear his views and recollections, many of which are the same as what he shared with me, when I was just engaging in my training as a sophomore at SJSU.

Thanks to you both!!!

Gary,

Thanks so much for posting this.Roy has such a great story to tell from that famous era.The photos are absolute treasures.

Ted,I remember you talking about Roy when you & I met at ACCD.Small world.

Thanks!

john

Roy,

Speaking on behalf of the Automotive Designers Guild, it’s great to see another Guild Member showcase his creative design work. We would hope that other Guild Members will take inspiration from this fine presentation and put together their own show and tell story. John Manoogian’s interview with you was excellent, prompting you with good lead in questions to your insightful recollections. Your visual contribution here is equally exciting. Thanks for sharing

this wealth of automotive design history!

John M. Mellberg

ADGuild Support

thanks for an excellent article. the illustrations are wonderful. will look at them over and over.

very inspring, thank you very much mr lonberger!

Wow! I’m a bit embarrassed to admit that I don’t recall Roy’s name, although we were probably contemporaries at ACCD. I was in classes with Ira Gilford and Dave Stollery, and remember that Terry Henline was in classes a bit ahead of me.

The story that Roy tells of working at GM during Mitchell’s era is not surprising, but the pace that he describes and the fluency of his drawing are completely intimidating to me. I guess I’m glad that I went elsewhere and did other things rather than working at GM as I had intended.

Whew!

I’m really sorry I never had the chance to meet Bill Mitchell, I love stories about him, especially the Mitchell-isms, like “crease the fenders like well pressed pants” and “styling small cars is like tailoring suits for a dwarf”. Anyone remember some others? What a character he must have been to work for!

I know some of his comments are inappropriate by today’s standards, but if you worked there at the time, I bet you’re thick skinned enough to know Bill’s humor, please share it here.

To Jeffrey Goldstein’s commentary about Mitchell-ism’s, here’s a couple that I’ll never forget. Bill walked into the Adv. Pontiac Studio one AM when we were all at the wall boards doing front end tape drawing studies, and as he approached the one closest to him, he blurted out, “this front end looks like a Mosquito’s a–, stretched over a fry pan!’ He was serious, and we were all ready to burst out laughing, but didn’t until after he left. Another one was, “you can put Lipstick on a Pig, but it’s still a Pig!” He was a ‘one of a kind!’

just a few “Mitchellisms”:

“you don’t get smart by being young”

“Flatter than piss on a platter”

“looks like it was designed in the hallway by a French designer”………….. i.e.too tall & narrow

“if you’re going to rob something,you rob a bank,not a gas station” i.e.borrow from Rolls or Ferrari

I remember Roy, great guy,s pent too short a time with us, knew he was going on to bigger things!

Thanks Roy for a delightful and informative presentation! Also, thanks to John Manoogian for a great interview. These stories connect with me very personally, because I found the path to automobile design through GM’s Fisher Body Craftsman’s Guild. I will never forget the excitement (16 year old) as Michigan’s winner in 1964 to sit in concept cars (Monza GT and Mako Shark!) and to meet Mr. Mitchell, Mr. Jordan, and many GM designers. That introduced me to Art Center. A big deal for a Traverse City kid! Thanks. SR

Hello Roy,

I did not know about your history in Studio X. I was also assigned there after a short time in the “bull pen”. I worked on the “4 fendered farkle”. It was amazing to go nearly straight from school (although I was in the GM summer program the previous summer) into Studio X. I guess I was given John Shinoda’s desk because there were some of his drawings in there of the original sting ray. I was too naive to realize their value and tossed them out to make room for my own sketches.

A couple Bill Mitchellisms I remember from Studio X are:

– “Designing in Studio X is like trying to play a trombone in a phone booth” (studio X was extremely small and hidden in the basement with no windows).

– “Designing in Studio X is like trying to f__k a French whore in a rain coat”

I also followed you through FMC, IDSA leadership and teaching at SJSU (where I still teach along with teaching at The Academy of Art with Tom Matano).

Hope all is well with you.

Jim Shook

Great to hear from you Jim. Did not know that you had your turn at Studio-X. Why not prepare an article about your GM experiences? I am sure that we would welcome your contribution to this important and valuable site.

Thank you so much for keeping this article on this site. What a marvelous trip to a time and place that produced some of the most remarkable and influential cars in history, with some of the most important masters of design. Every time I hear about that era and its artists, see the products of that imagination, I am moved to pick up a pencil and try, ever ineffectively, to translate the passion it stirs up into my own auto designs. These days, that passion is a welcome warmth that I treasure.

Hello, I worked for a short time in studio X under the main design staff building. Chester Angeloni was my leader and chief Sculptor. We were working on the three wheeler that Bill Michell wanted to have a running vehicle made. There was one other sculptor but I do not remember his name. There was an assistant engineer also, and I think it was Al Swensen.

No one was allowed to come into the studio because Mr. Mitchell kept the studio closed. One day Chuck Jordan came in and Bill caught him and kicked him out. Larry Shinoda and I worked together for a short time across twelve mile in the warehouse on a corvette. Chester was also there. Larry told me how his family was placed in a camp during World War Two because they were Japanese.

John Manogian and I worked together many years later in Cadillac Studio. Thank you for this memory recall of studio X. I have a plaster sculpture reproduction by Chester Angeloni of Arturo Toscanini, conductor of the New York Philharmonic Symphony. I need to have it made in bronze. Spelling is not one of my best abilities. Sorry!