Alex Tremulis: Elephant Ears, Theater Receipts, and Other Stories

By Jim and Cheryl Farrell

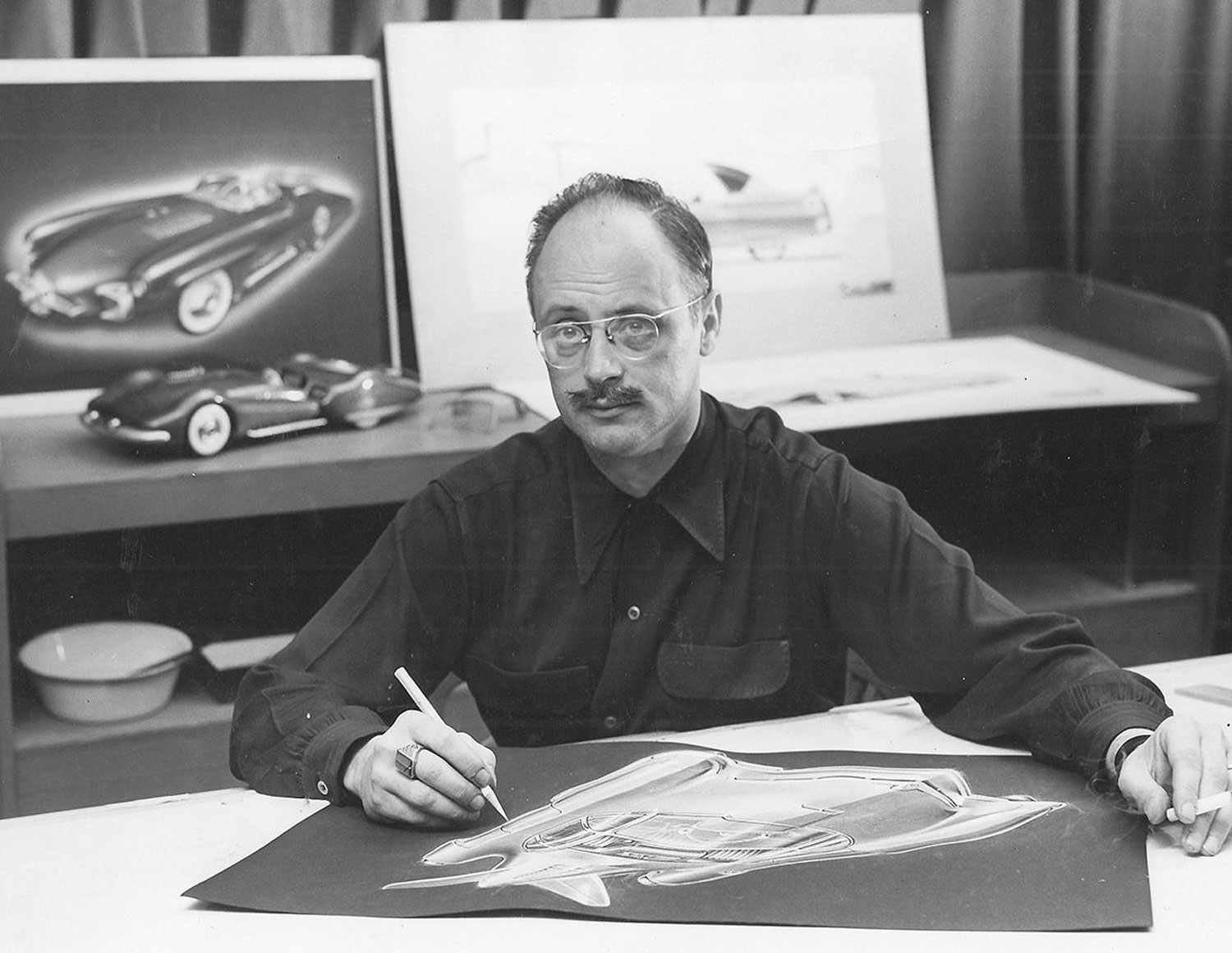

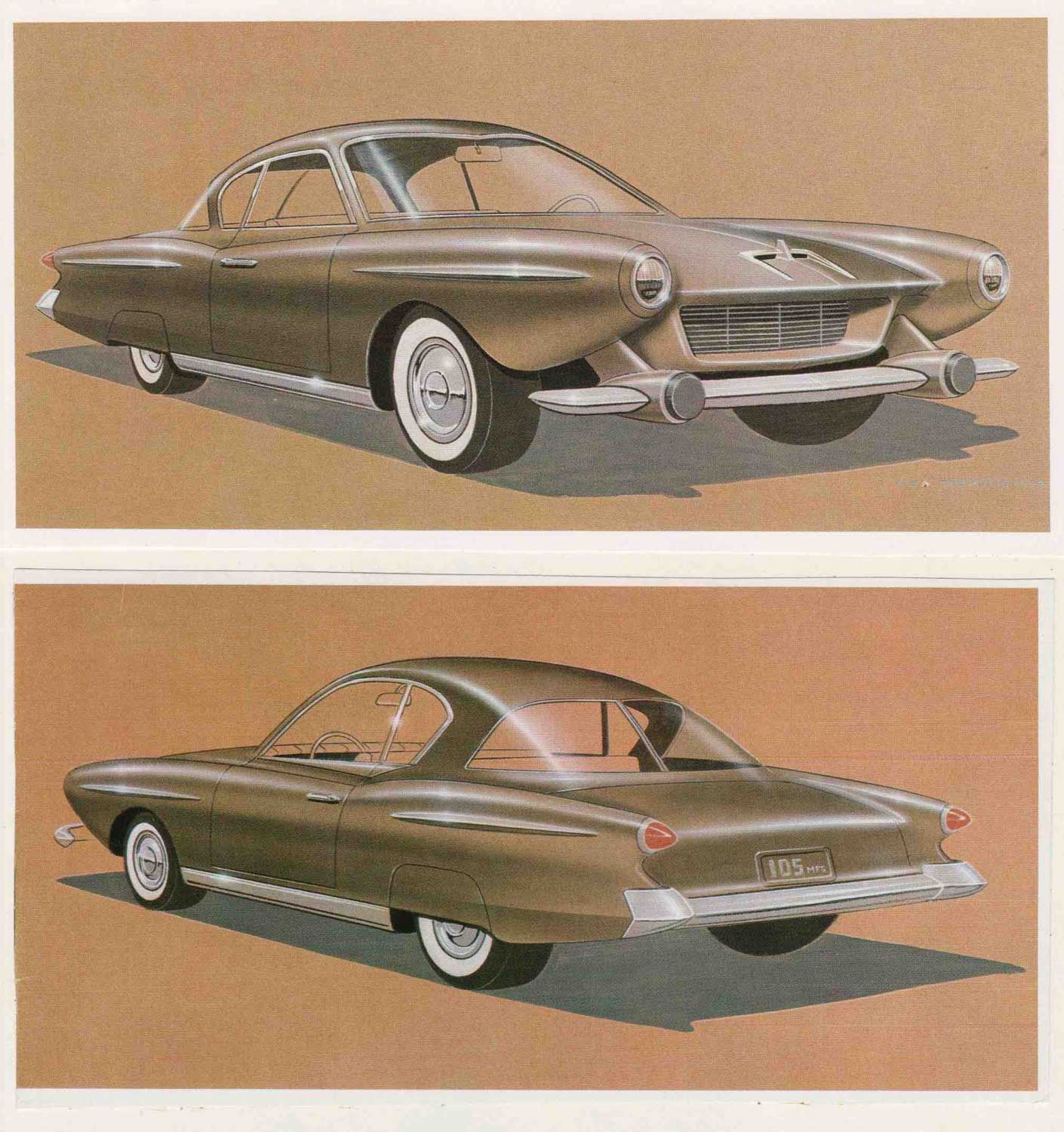

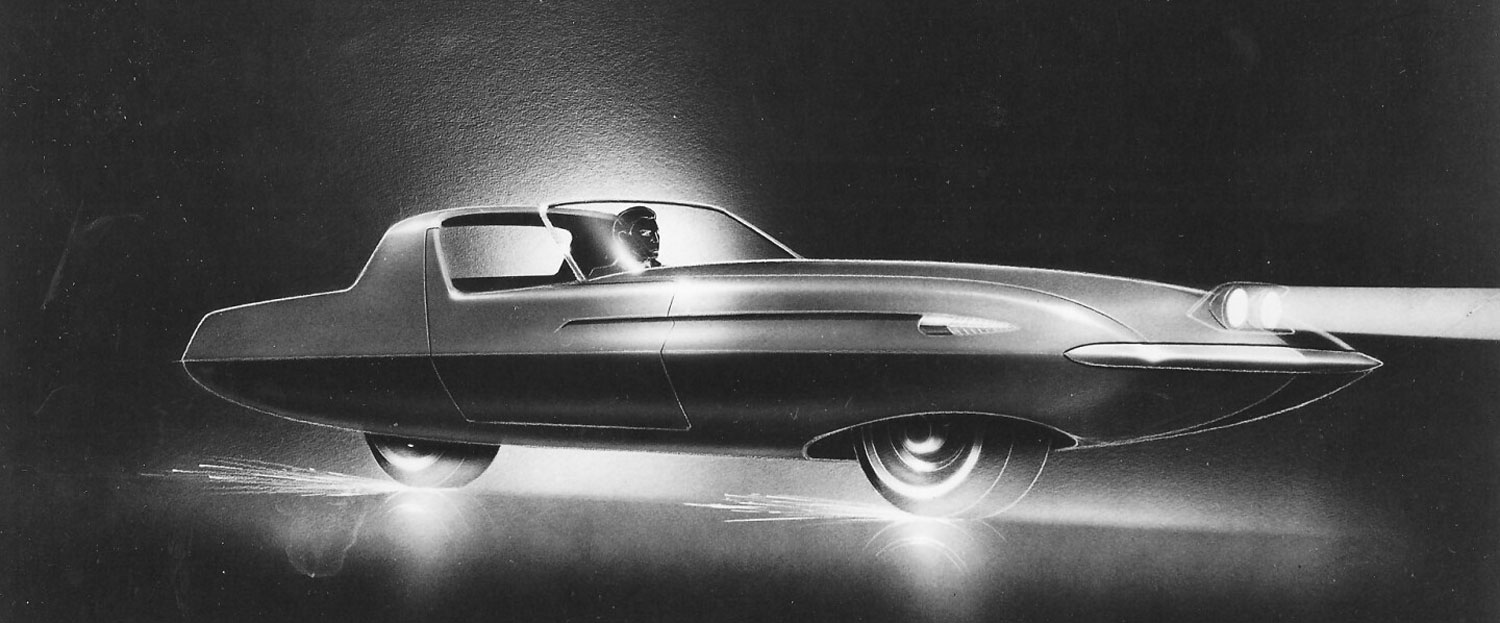

According to designers who knew and admired him, Alex Tremulis was a serious student of aerodynamics when it was not a very popular subject. At the time, Ford Design Center management didn’t think aerodynamics had much if any effect on car design. And they had little patience with Tremulis and some of the “experiments” he performed in support of his aerodynamic research—which management saw as “misguided.”

Tremulis started at Ford in 1952. His first assignment was temporary in Mercury studio, where he took a dislike of one the grille proposals for the ’55 Mercury grille. On show day, Tremulis got there early and began painting every other tooth across on front of grille with black paint. When executives arrived to choose the production grille, Tremulis pulled up a modelers’s stool and acted like he was playing the piano on the grille. Everyone smiled—and promptly picked that grille for production.

Elephant Ears

In the mid-1950s, Tremulis took a big plaster elephant he had been given by a clay modeler to a test in a wind tunnel Ford was renting for $200 per hour. The only problem was that Earle MacPherson, Ford’s chief engineer, who had a low opinion of designers anyway, showed up just as Tremulis was testing the elephant for wind resistance. MacPherson asked Tremulis what the plaster elephant was doing in the wind tunnel. Tremulis told him he was “testing aerodynamic braking,” and that he also planned to test the elephant after the ears had been cut off. At that point, a disgusted MacPherson left the building shaking his head.

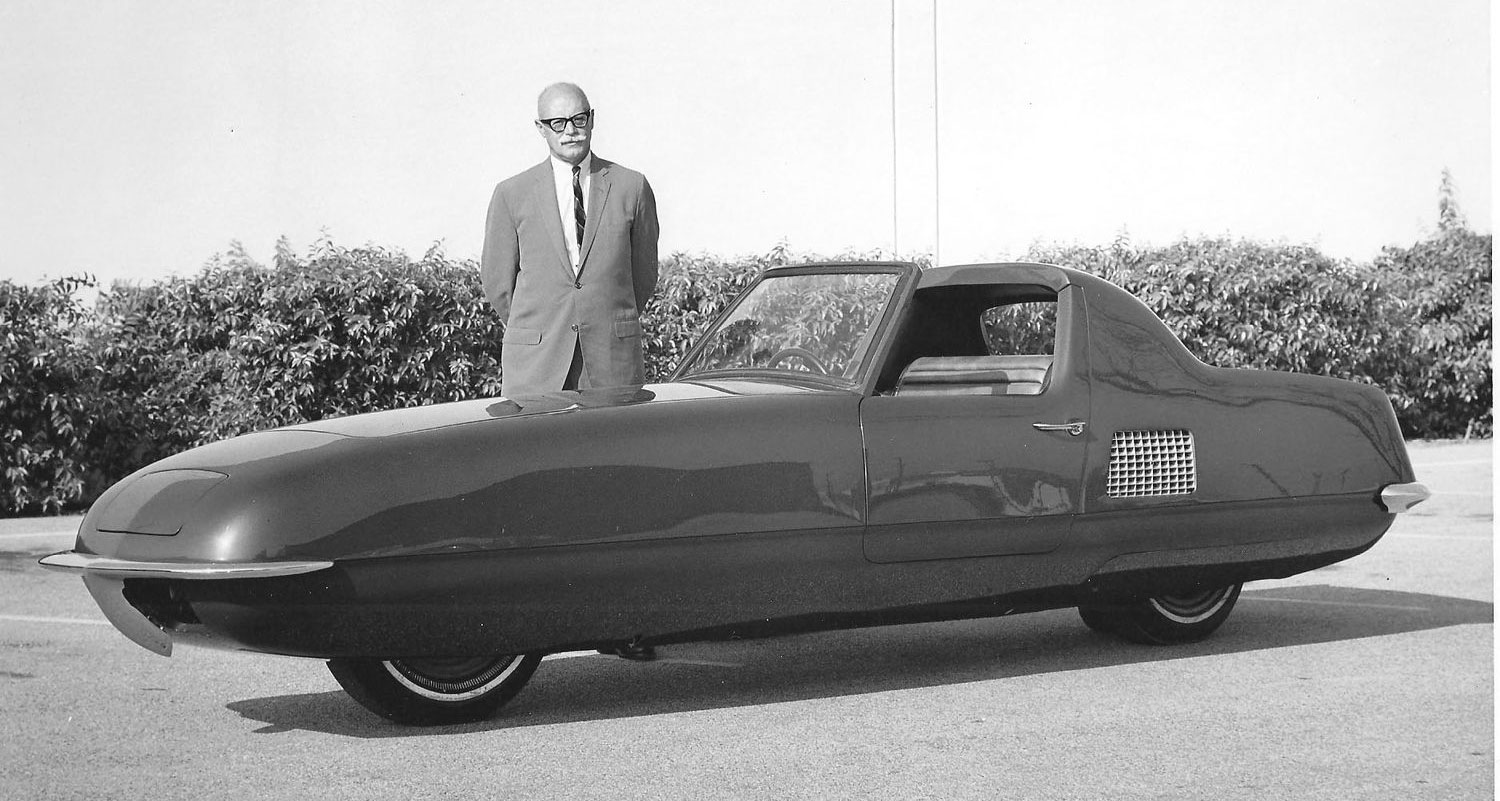

Remote Control

On another occasion. Tremulis was “driving” one of the remote control models he and designer Romeyne Hammond had built to see how far away the controls worked. He found that the model could be controlled up to 1.25 miles away on Oakwood Blvd. Unfortunately, the small model stopped traffic one morning at an intersection some distance away from the Design Center when chief engineer MacPherson was trying get to work. That ending driving remote controlled models on public streets!

Aerodynamic Research

Once, Tremulis’ scientific experiments included capping a cardboard vellum tube with a metal cap and filling the tube with air from the other end until the cap was blown off with a loud bang. So he wouldn’t have to chase the cap when it was blown off, Tremulis attached a long string to the cap so he could reel the cap in. During one of his many “experiments” with the tube, the cap and string sailed over the wall and got caught in the egg-crate ceiling in chief designer Bob Maguire’s office while Maguire was conducting a meeting. Every time Tremulis pulled the string, the stuck metal cap banged against the ceiling, until Maguire had to stop the meeting so Tremulis could climb up on a ladder and retrieve the metal cap. Tremulis apologized to Maguire, explaining that he had just been “researching high-speed aerodynamics.”

Tremulis to the Rescue

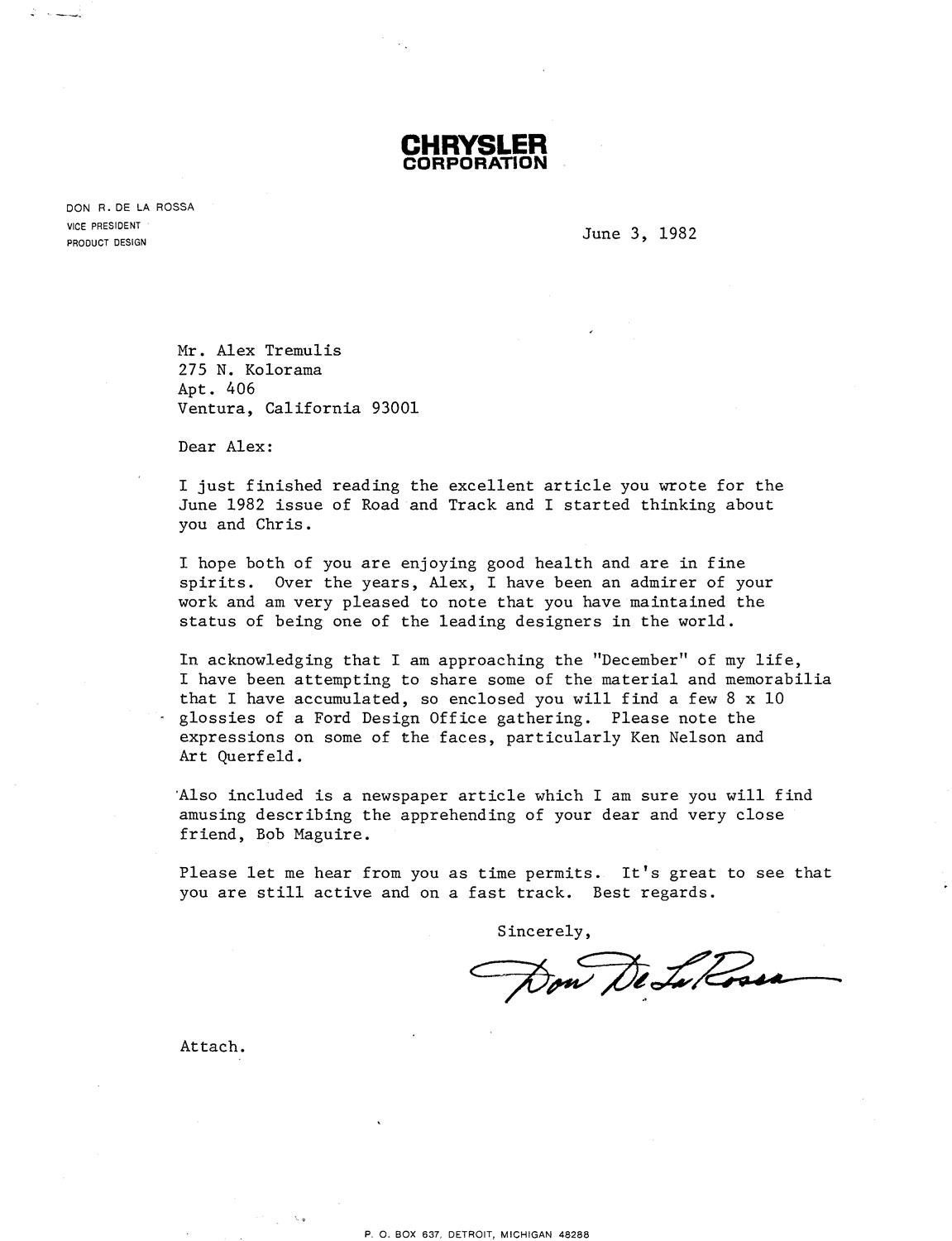

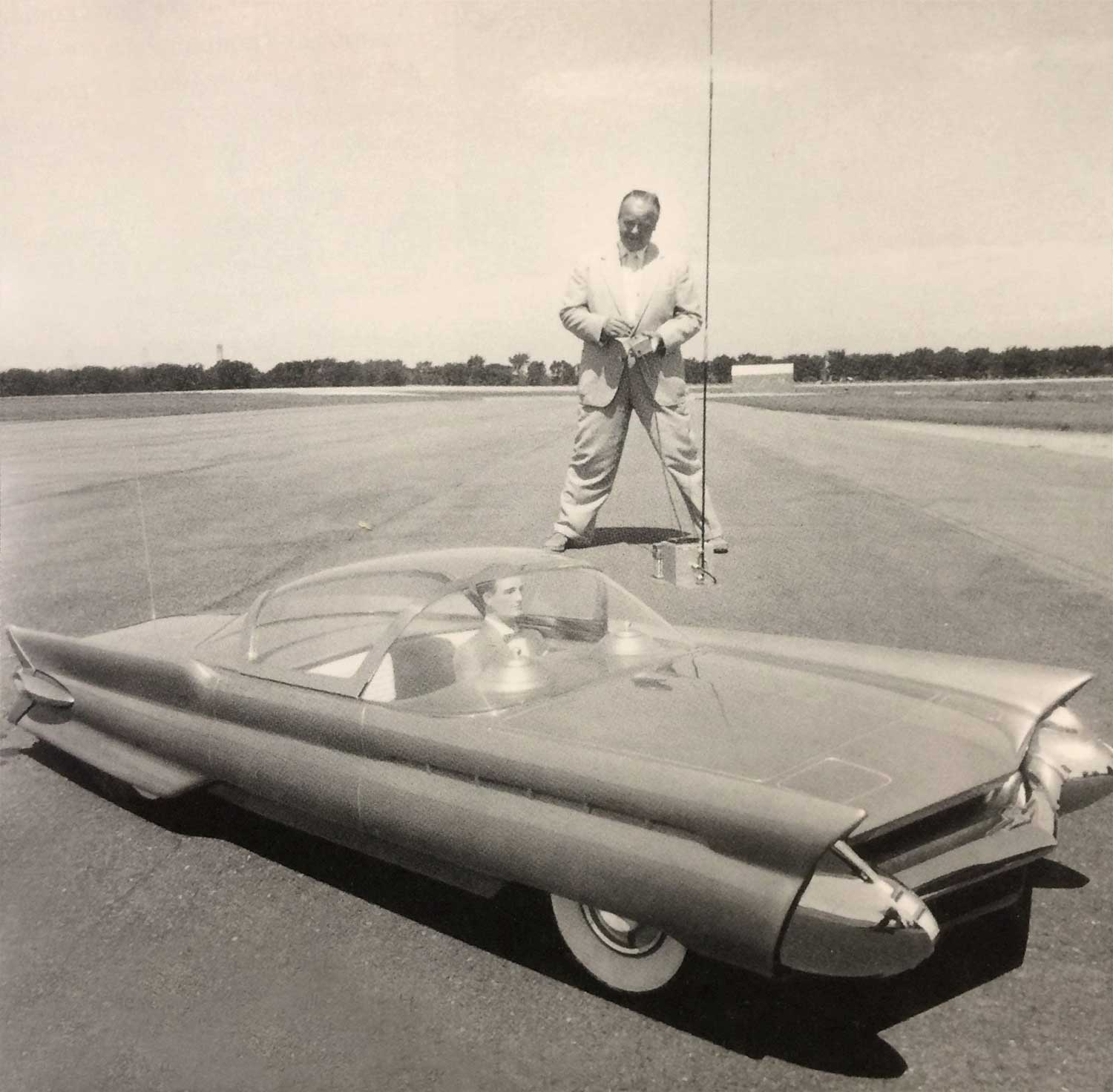

In March, 1959, Don DeLaRossa, who was then head of the Lincoln design studio, had just picked up his 1957 Jaguar XK-140 roadster from the Design Center paint shop where it had been detailed. DeLaRossa had just bought the car. It had a Corvette engine, and DeLaRossa wanted to show Maguire how fast it was. DeLaRossa asked Ken Spencer, one of the Ford designers and Maguire’s nephew, to put the license plates back on the car. Spencer tried but the holes in the plates wouldn’t line up with the brackets, so Spencer took the plates to the shop to redrill the holes. In the meantime, DeLaRossa and Maguire came out, got in the car—with Maguire driving—and didn’t realize it had no license plates on it. Soon after they started up I-94 (at that time called US-12), a deputy started chasing them with lights and siren on. Neither DeLaRossa nor Maguire realized the cops were after them or were anywhere around. Another deputy soon joined the chase, but at over 110 mph, he couldn’t keep up. Still DeLaRossa and Maguire hadn’t seen the deputies and couldn’t hear the sirens over the roar of the engine. About 30 miles later, a surprised Maguire and DeLaRossa were pulled over at a road block near Ann Arbor, and both were taken to an Ann Arbor jail.

Neither DeLaRossa nor Maguire knew anyone who lived in Ann Arbor, except Tremulis. So, guess who they called to bail them out? By that time the banks were all closed and Tremulis’ only source of ready cash was a friend who ran the local movie theater. He had the day’s receipts in small bills and change, which were borrowed and used to bail out the two Ford executives. Maguire swore Temulis to secrecy, but by the time Maguire arrived at work the next morning the news was all over the Ford Styling Center about the arrest and jailing of the two bosses. Maguire blamed Tremulis for blabbing, which he denied. The next day, however, the arrest of the two Ford executives was in the local newspaper. Only years later did DeLaRossa acknowledge he had been the one who spilled the beans.

Burnouts

In 1963 someone left a new Cobra in the studio with the keys in it. The temptation was too great for Tremulis, who decided to test the new Cobra for its aerodynamics and ability to stop. So he drove the Cobra back and forth on the maple floors of the studio until everyone in the Design Center could smell the burnt rubber and see a thin cloud of smoke that had spread throughout the building. As a result, head of the Ford Design Center, Gene Bordinat, asked Tremulis to resign.

Fast forward to 1982. DeLaRossa had been hired by Chrysler as its vice president of design. For reasons that can only be guessed, DeLaRossa sent the attached letter and copies to Tremulis, who was by then semi-retired and living in California. The letter enclosed a copy of the news article about DeLaRossa and Maguire’s arrest along with photos of some of the characters/designers who worked at the Ford Design Center.

Life is sometimes stranger than fiction! If you think this type of antics only went on at Ford, then you are kindly invited to read the Dean’s Garage book about similar antics that occurred at GM.

Books by Jim and Cheryl Farrell

Ford Design Department—

Concepts & Showcars

1999, 10×13, 400 pages, Fully indexed

900 photos. Includes 150+ designers and sculptors, and highlights 100 concept cars.

ISBN 0-9672428-0-0

Lincoln Design Heritage:

Zephyr to LS (1936-2000)

2021, 10×13, 480 Pages, Fully Indexed

1,600 photos and illustrations

ISBN 978-0-9672428-1-1

The Ford book is $50 plus $7 S&H (US). The Lincoln book is $85 plus $10 S&H (US). Both books bought together are $110 plus $17 S&H (US). To order, email: cfarrell57@gmail.com

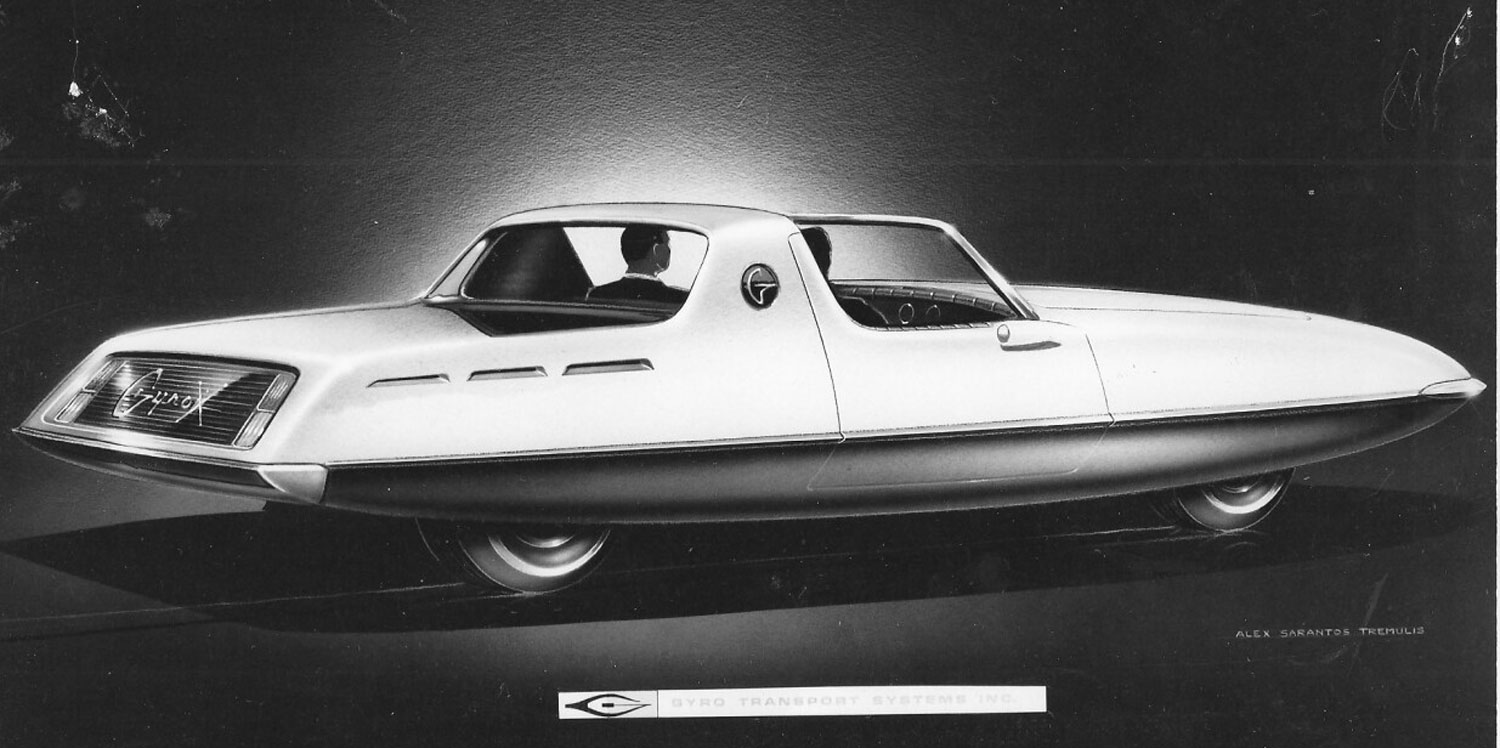

Most interesting. The car GyroX was found and restored sone time ago.

https://youtu.be/JJBMMJWHO6k

Not so sure of the “burning rubber” incident, I witnessed a different event with Alex which has me questioning the story by the Farrells.

Alex was my supervisor, at the time of this event, and one night on overtime we had to move the production AC Cobra sitting in the way. We needed to get to the large “blackboards” blocked by the car.

“I’ll move the car and you fellas move the rolling boards (blackboards).” Alex told us.

Alex got in, turned the key and the electric fuel pump began clicking and the engine roared to life. We all loved the sound!

Alex eased out the clutch & the car didn’t move. Making sure he was in gear Alex gave it more gas. It still didn’t move! By this time the rest of us were in near hysterics! Soon he had it almost redlining & no motion.

The car was so lightweight it was just spinning it’s wheels and burning through the white oak herringbone pattern flooring. (Sorry Farrells, none of the studios had maple flooring & I spent 21 years as a designer at Ford Design Center working in every studio Ford had.)

All of us, including Alex, spent the rest of that night’s overtime on our hands and knees hand sanding the floor & spraying it with shellac to hide the damage.

I question the earlier tale about Alex driving the car as alluded to above.

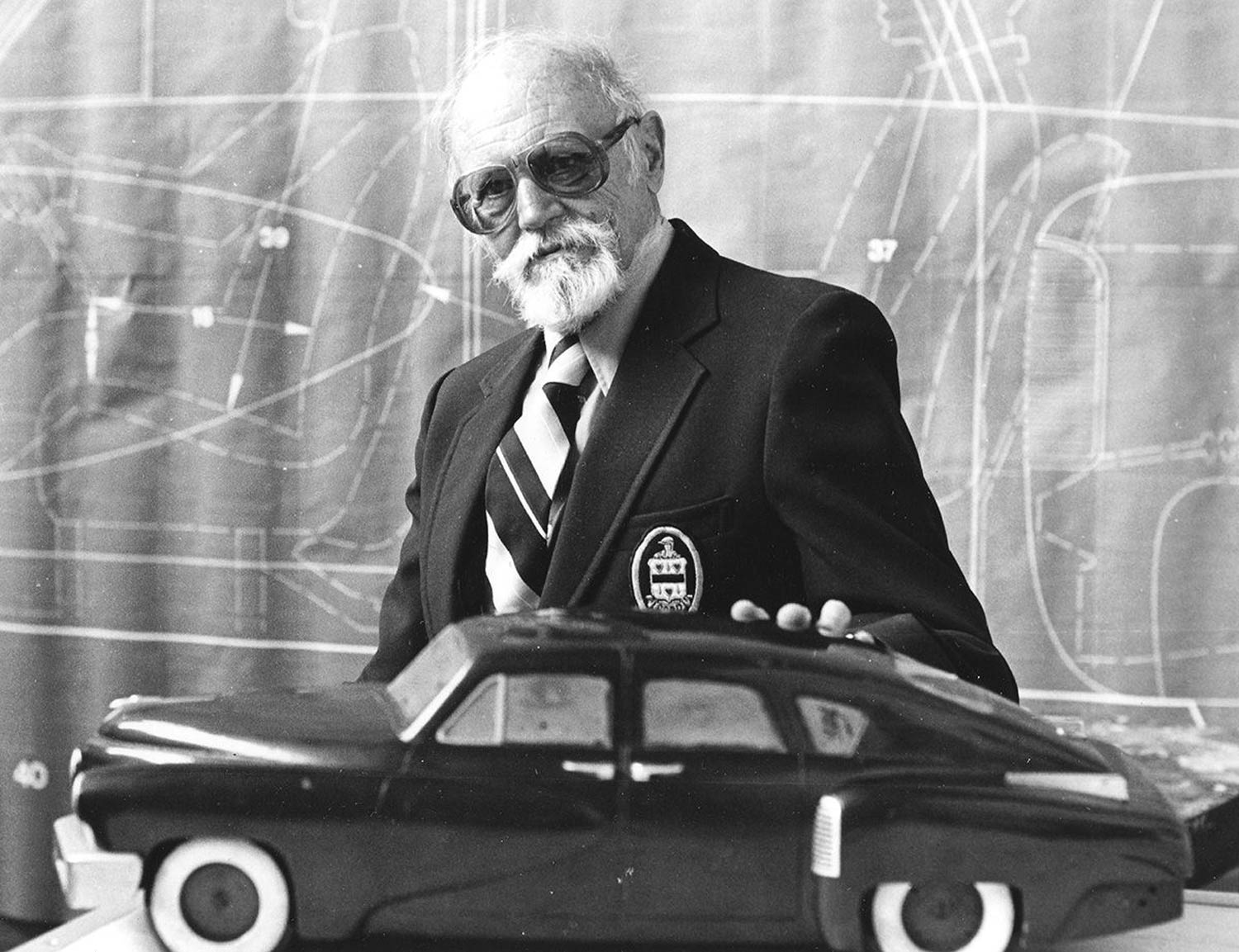

Alex was a wonderful guy and great boss who stimulated the creativity of everyone who came into contact with him. I wish he & Chrissy were still with us.

Phil Payne

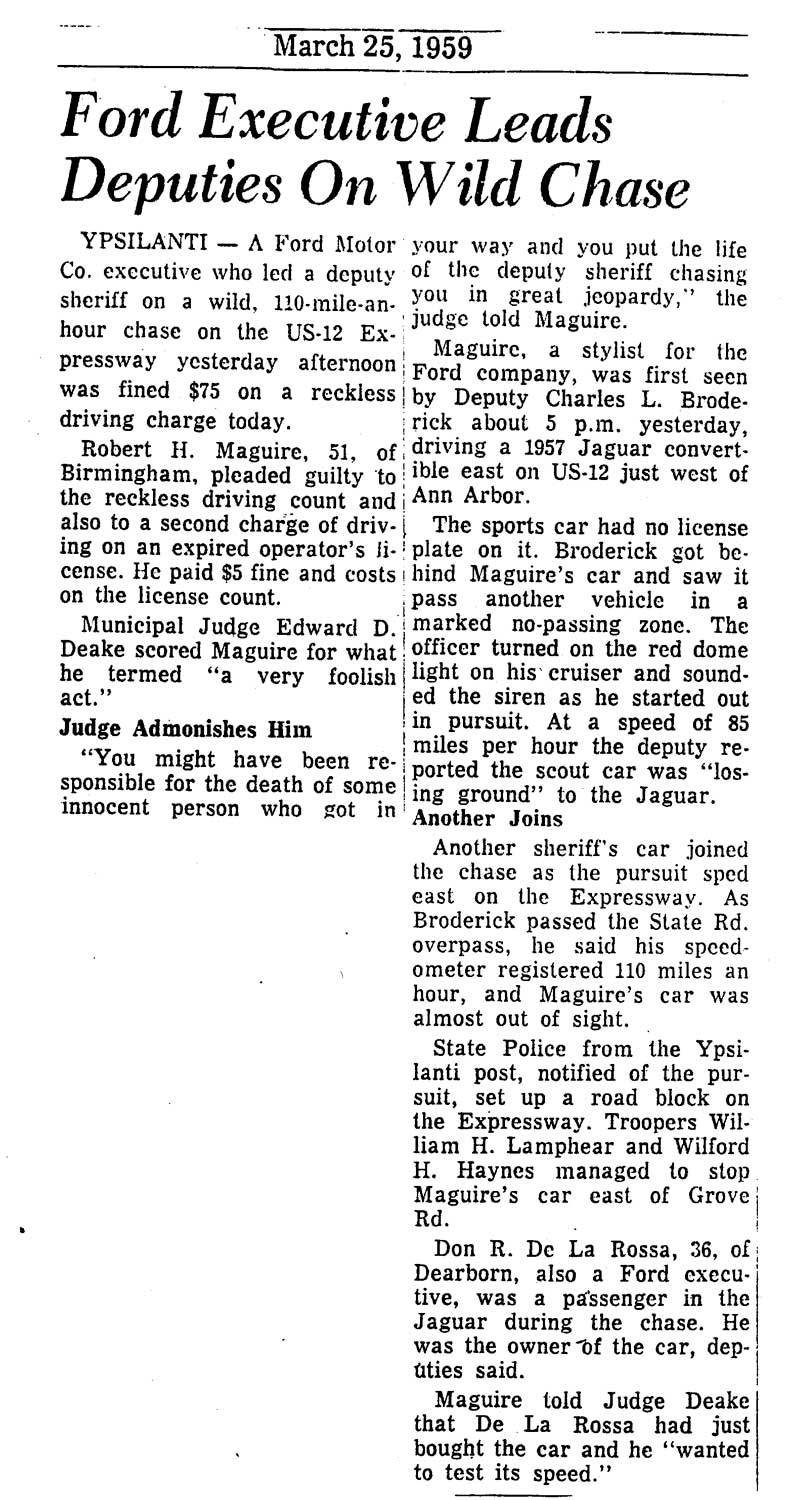

Alex Tremulis had so many stories that kept everyone entertained. At Ford, he’d play in Bob Thomas’ band, but not just any instrument, he’d play his airbrush between his fingertips. He’d also pipe it in over the PA system, especially annoying Bob Maguire, one of his favorite targets. At Tucker, he exclaimed to Preston Tucker that he had the ultimate safety solution: He had hung two football helmets on springs from the headliner of the prototype. Tucker was not amused. He’s also credited with putting the musical notes on the rear fender of the 1958 Oldsmobile and rearranging the letters into “Slobmobile”. He also put a miniature Henry Ford II into the 3/8 scale Ford Mexico as well as a 3/8 scale bow-tied Romeyne Hammond into the La Tosca, much to the chagrin of Charlie Waterhouse. There’s so many more stories to tell! He grew older, but he always kept his sense of humor and love for practical jokes. A life well lived!

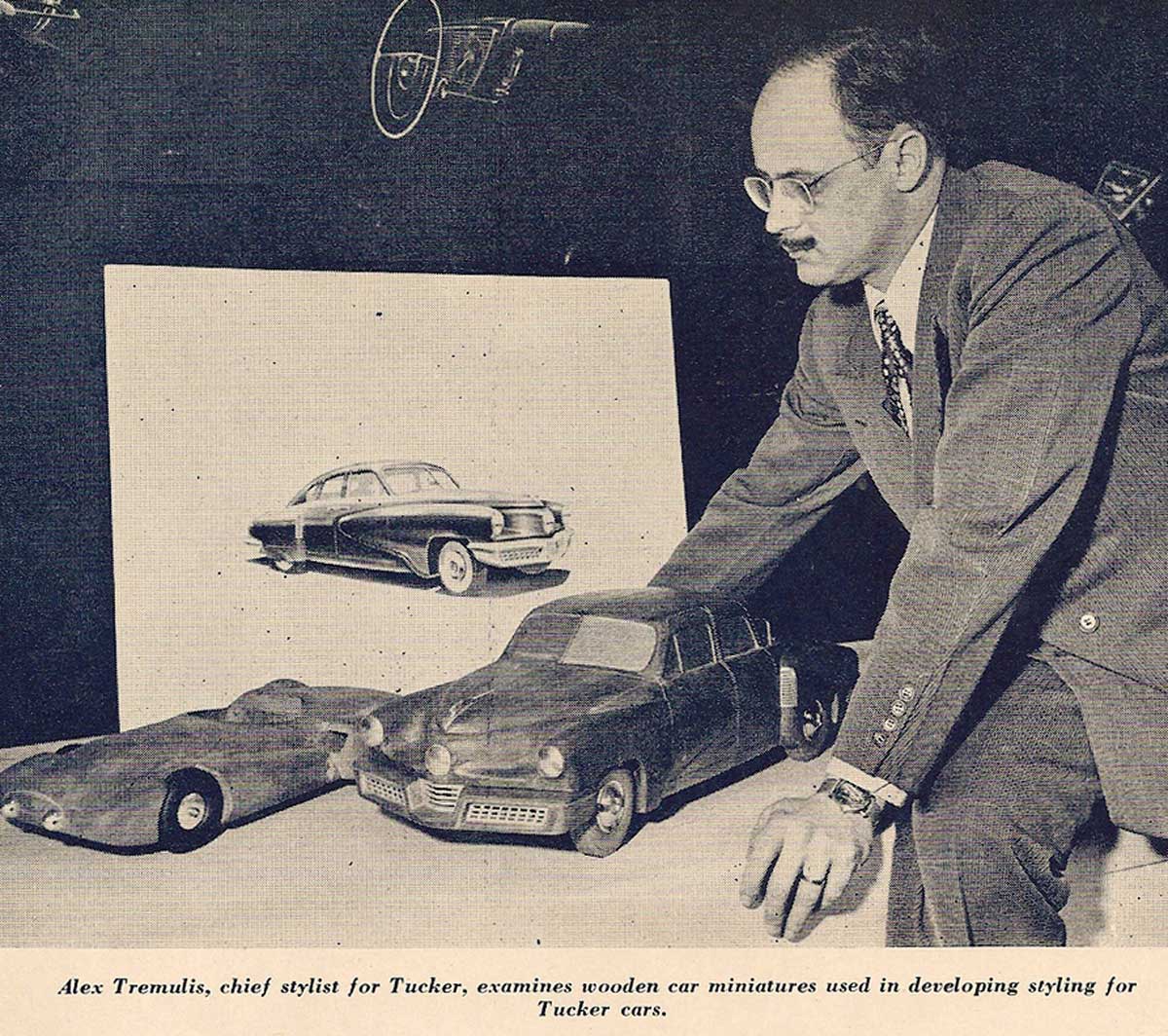

On my first day at Ford Styling in January 1963, I was introduced to Alex Tremulis while he was working on the full size model of the Turbine truck. At that point, it was a clay monolith 13′ high. A blob. At the time it was called “Tremulus Folly”. But he proved everyone wrong and designed a very interesting vehicle.

But that is not the point that I want to make: When introduced to the man, he welcomed me into Ford Styling and told me that he was there for me if I needed any answers or help. Others have talked about his humor. To me, he was a gentleman.