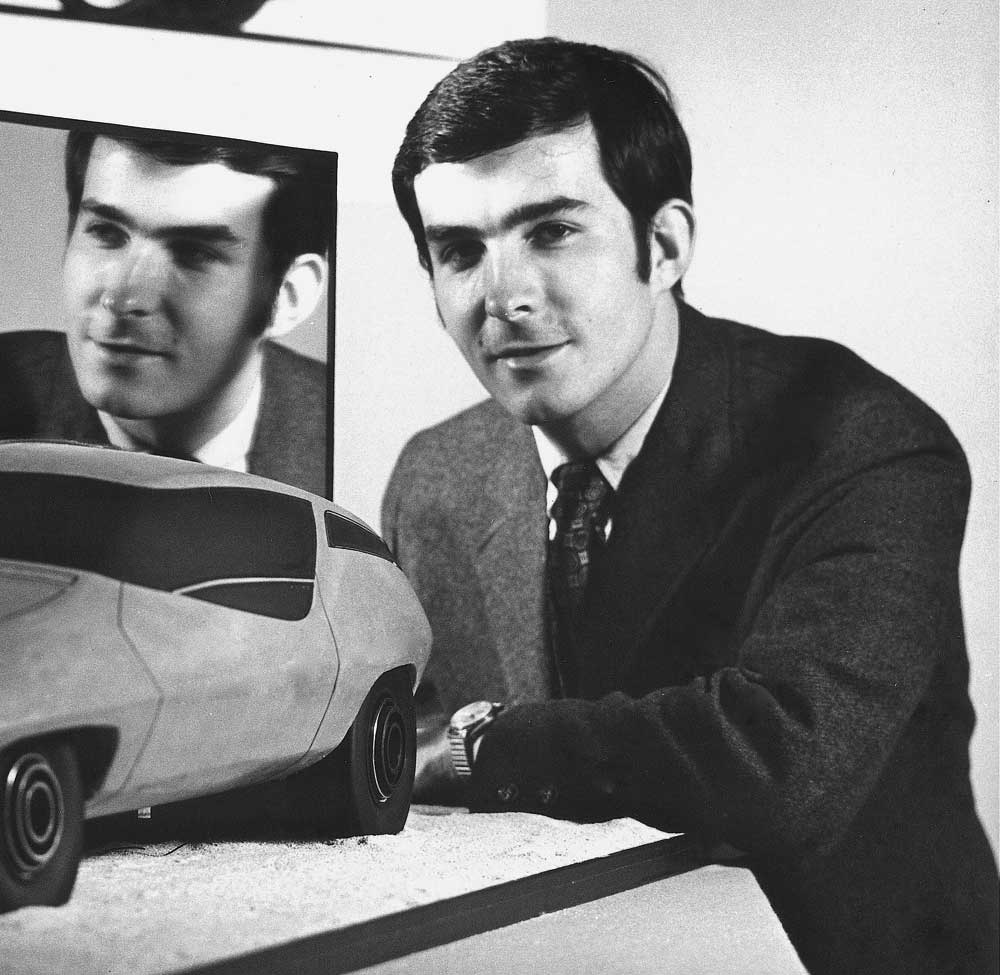

By Dick Nesbitt

I started at Art Center College in the fall of 1967, when the psychedelic era and flower power were in full bloom (heh-heh). I was 21, and it was an exciting time to be in Los Angeles. Art Center required an extreme level of discipline, so any involvement in the general activities of the day, including hair length and dress, was not an option. As a Transportation Design major, our first Transportation class began in the second semester. Some of the students already had professional design experience, and were attending to get a formal graduate degree for better career opportunities. Don Wyatt was in our class, and had been a Tech Designer at General Motors Design Staff. He was familiar with the sketch and design techniques in use by GM designers, and he could hold his own with many of them. I was “blown away” by his technique skills at Art Center, as he exhibited his work for critique every week in each class. Gaylord Eckles was a Product Design major from San Francisco, and he was an incredible talent. From the simplest sketch to the most detailed design models, his work was truly exquisite and always delightful. Eckles later became an award-winning instructor at Art Center, and I am sure he was a tremendous inspiration to many fortunate enough to have had the benefit of his knowledge and design wisdom.

Our instructor for the first Transportation Design class was Hugh Jorgensen (click here to read an interview with Hugh Jorgensen). In my opinion, he was the best possible choice for our introduction to the very challenging and competitive world of professional automotive design. Jorgensen was always optimistic, motivational,positive and supportive in his critique of our work. He was never negative or derogatory, and he inspired much-needed confidence.

For our second Transportation Design class in third semester, our instructor was Strother MacMinn. “Mac” was a legend at Art Center and in automotive design centers and related publications all over the world. He has had more influence on the careers of more automotive designers than any other single individual—ever. Unlike Hugh Jorgensen, Mac could be brutal and scathing in his student critiques. It was high praise, indeed, to receive any compliment from Mac!

Fifth semester was the beginning of Advanced Transportation Design classes for two days each week, and Mac was the instructor. For this semester, we were required to first design and then construct one-fifth scale, high-density urethane foam models of our final selected sketch theme directions. Mac normally was the instructor for the two day sixth semester Trans classes. Two new instructors were brought in for our sixth semester, because Mac was taking a sabbatical in Detroit during this time in 1969. The two instructors were Harry Bradley for one day and renowned Shelby designer Pete Brock for the second day! Harry and Pete were only scheduled to teach this one semester, but Harry Bradley stayed on for many years after. What a fantastic experience having Bradley and Brock as our sixth semester Advanced Transportation Design instructors.

General Motors, Ford, and sometimes Chrysler would come out to Art Center every other semester to assign a design project for which they would provide a final critique for each Trans students presentation. I was honored to participate in a General Motors Design Seminar for my seventh semester. The GM design team was represented by the legendary Dave Holls. Our final presentation included finished renderings, design development sketches, and a package component layout illustration. Also included was a space buck skeleton framework in scale to accurately illustrate in three-dimensional form the placement of seating and drivetrain components within equally spaced sections, indicating the outer body shell surface contours. Complimenting the space buck was a detailed clay model.

Our GM design assignment was the end of an era, as it turned out. We were to design a close-coupled front wheel drive 455 V8 personal luxury coupe for the mid-seventies. I selected Buick for my proposal, and created the “Centuro” name as a contemporary variation of Buick’s famous Century and Centurion nameplates. My design theme incorporated “applied form” raised rib forms over the front wheel openings and “sub windows”. Sub windows were smaller, fixed window areas that later became more well known as opera windows, as seen on the 1971 Cadillac Eldorado. The Centuro also included alloy wheels and a reverse “Z” line as a variation of Buick’s familiar “Sweepspear” on the body side with urethane body color front and rear bumper surfaces as pioneered by Pontiac’s GTO in 1968.

Some examples of Dick Nesbitt’s student work from Art Center.

The Art Center Bandsaw.

Late nighters or all nighters were the norm. It didn’t start out that way. When the semester first starts, you promise yourself that you’ll work on the class assignment that night. But after a couple of weeks you find yourself scrambling to get tomorrow’s assignment done. I fell asleep briefly standing up during a critique once. But that is another story.

One day I was in the shop waiting for some tool at the tool crib window. Near where I standing was a pretty big band saw. Pushing something that needed to be shorter through the blade was a student with that glazed over “I’ve been up a few nights” look. The thing he was pushing was a chunk of hard wood with the table tilted about 30 degrees, so it was feeding fairly slowly. The student was concentrating hard on what he was doing. In his state of mind dealing with several factors at once was probably not much of an option. Not having any other distraction, I watched the action at the band saw. I soon noticed that the student’s thumb was strategically positioned to hold the wood to give the most stability to the endeavor. I also noticed that if he maintained that grip, both his thumb as well as the wood would soon be shorter.

The feeding was going slowly enough that I could wait and see if he moved his thumb. But he kept pushing—past the point where I would have adjusted my grip on the board as to not whack off any appendages. Still, there was still time for him to act. Not a lot of time mind you, but some. But he kept pushing, way past my comfort level, and his thumb moved precariously close to the blade. It wouldn’t do to watch him cut his thumb off. I left my place at the tool crib window, stepped over and grabbed the student’s arm.

“Hey! Be careful. You’re going to cut your thumb off!

His response? “What? Oh. Yeah. Thanks.”

—Gary Smith

I had Hugh Jorgensen as a Trans instructor in a later semester, and remember him just as Dick Nesbitt describes. He told us that he bought a brand new Jaguar XKE. I’m not sure what year, but it had to have been around 1970, so it was a stunningly beautiful car. He also told us that it spent most the time he had it, which wasn’t long, in the shop. So he sold it and bought a new Corvette. A big block no less. Being a Corvette enthusiast, his confession elevated his position in my young eyes. I also remember Strother MacMinn’s blue ’70 Camaro, and Ted Younkin’s blue short-bed Chevy pickup. When Ted took delivery of the truck, he noticed that there was a blank face where some optional gauge should have been. He told us that it became his humility gauge, reminding him that he didn’t have everything.

I also remember walking into the shop one morning and seeing a rather large, nasty hole clear through the wall, about 4″ x 6″ or so. It was gaping. You could see daylight. That was at the old school on 3rd Street. It was a sturdy, well constructed building. It turned out that the missile’s launcher was the planer. I never found out what really happened.

Dick Nesbitt’s Art Center Experiences story reminded me of the following: A story in the March-April 1992 issue of The Way of the Zephyr magazine, a publication of the Lincoln-Zephyr Owners Club.

DISTINGUISHED NEW MEMBERS

(condensed excerpts—story by Dave Cole)

“LZOC West, the southern California-based chapter of this club, has taken to advertising in various publications to attract new members. One such attractee joined both the LZOC West and the parent club was Robert C. Marcks, who used to be a designer in Lincoln’s advanced styling studio in the 1950s. Bob owned three classic Lincolns at one time.

Not long after Bob Marcks signed up, we got an inquiry from Richard Nesbitt of Arlington, Texas. Dick mentioned having once been a designer with Ford, too, so I inquired if he knew Bob Marcks. Know him! Nesbitt went on to tell how Marcks was recommended to him by the Art Center School in Los Angeles as a mentor, and how Bob encouraged him to become a Ford designer. Nesbitt later attended the Art Center on a full tuition-paid scholarship sponsored by Ford, and on graduation spent five years with Ford in various studios, including Lincoln-Mercury. Since then he has continued as a designer and consultant, and is highly regarded in the field.

Another former Ford stylist who has shown an interest in LZOC of late is Jack Juratovic.

Every member of LZOC joins me, I’m sure, in welcoming such distinguished company into our midst.”

(Why would I ever cancel my membership in a club that refers to me as distinguished?)

Dave Cole, talented Editor-in-Chief (for decades) of this fine publication, included more background on all three of us. (Jack Juratovic would make a fine contributor for Dean’s Garage.) Visit the club’s website: lzoc.org

Mr. Nesbitt,

I agree with you that Hugh J was a great Trans 1 instructor. I think I was in the first class he taught, as he was a stand-in for Mac who had injured himself in a fall at Heathrow Airport (Fall ’59). I didn’t find Mac a tough instructor, though (Trans 3 and 4 for me); he just seemed like a fellow enthusiast.

I envy your studies with Bradley and Brock. While I have met them both, I never had the benefit of their instruction, and I think that their styles would have been an interesting adjunct to Mac’s teaching.

I had Dick Collier for Trans 2. I was very discouraged by his teaching style and would have preferred almost any of the other ACS teachers.

Note: Just after I started ACCD, there was a bit of a rebellion by the upper class men. Dick Collier got “demoted” to teaching surface development and other entry level design courses. Another thing that happened while I was there was the abandonment of the dress code. So blue jeans, beards, and long hair became the norm. —Gary

I remember the cars the instructors and administrators drove. MacMinn’s red XK120 roadster, Don Kubley’s ’57 Continental, Harvy Thompson’s Rolls and Eugene Edwards’ 356.