The 1956 Lincoln, Part 2: The Secret That Wasn’t So Secret

By Jim and Cheryl Farrell

In the early ’50s, Ford was on a three-year design cycle. For Lincoln, the 1952–54 Lincolns were built using the same body and platform, and it was expected that the 1955–57 Lincolns would do the same. Thus, in early April 1952, Ford’s Product Planing Committee met at the Design Department to choose a new body style for the upcoming ’55 Lincoln.

The meeting started in the morning. Ford’s chief engineer, Earle MacPherson, was present along with many other Ford vice presidents including Ernie Breech, Ford’s executive vice president, who was really running the show. They looked at all the 123-inch proposals MacPherson and the designers thought might prove acceptable. None were, and just before lunch, Breech told everyone nothing he had seen was competitive, and he asked if there wasn’t something more exciting to see. Schmidt said he quietly stepped up and told Breech he had been working on a proposal in the back room that Breech might want to take a look at. Schmidt’s proposal was 12-inches longer than the proposals the committee had been looking at, and it had a three-inch longer wheelbase. Breech loved it and ordered Schmidt’s new proposal moved up front. When lunch was over and everyone had reassembled, Breech told them Schmidt’s new proposal was exactly what the new ’55 Lincoln should look like and that it was his choice. MacPherson vehemently objected, but the rest of the Committee followed Breech’s lead and choose Schmidt’s proposal as the new 1955 Lincoln

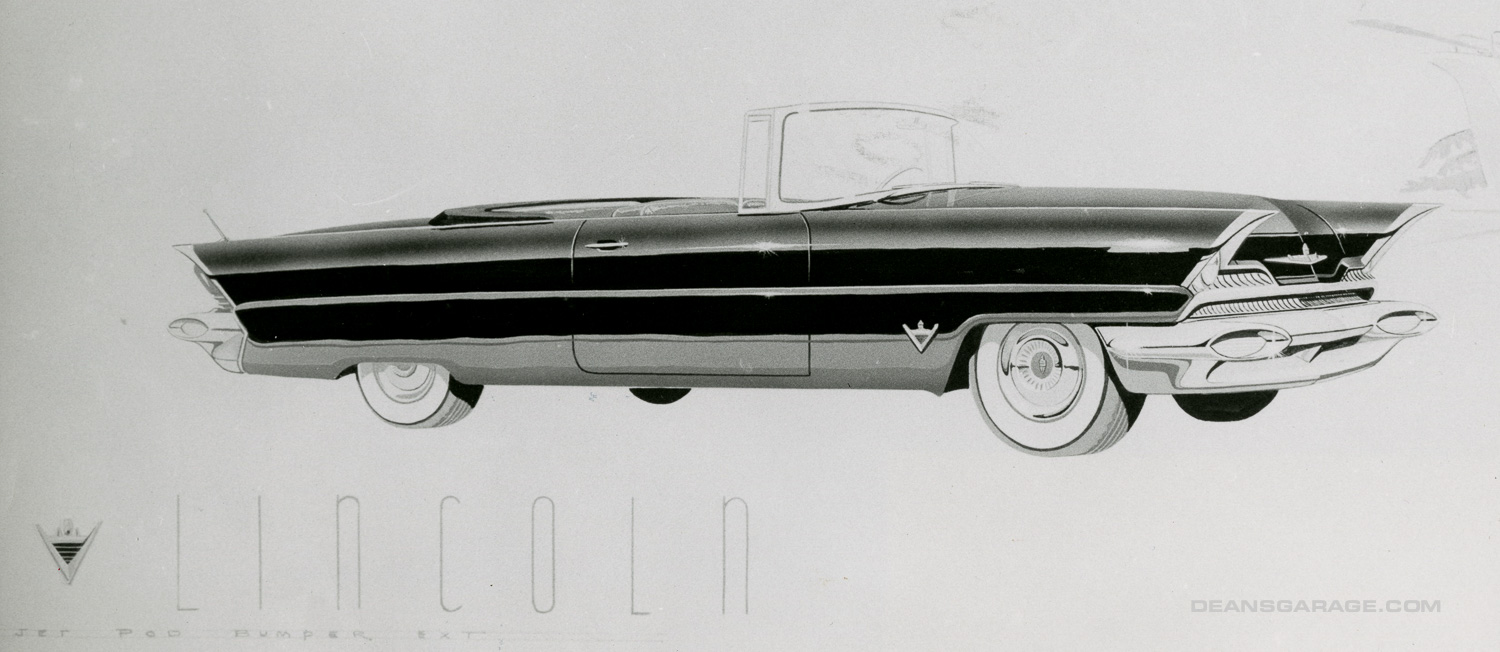

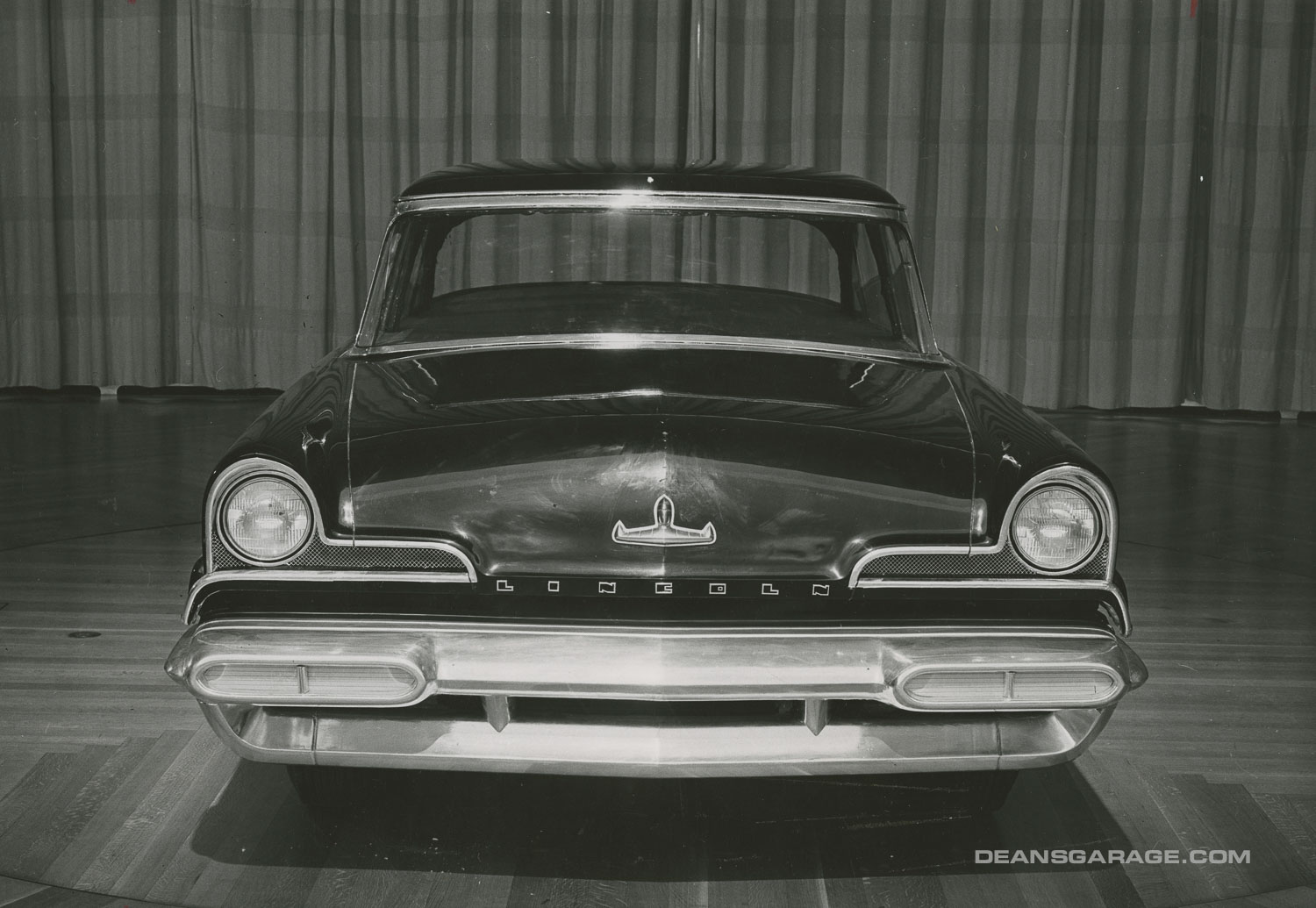

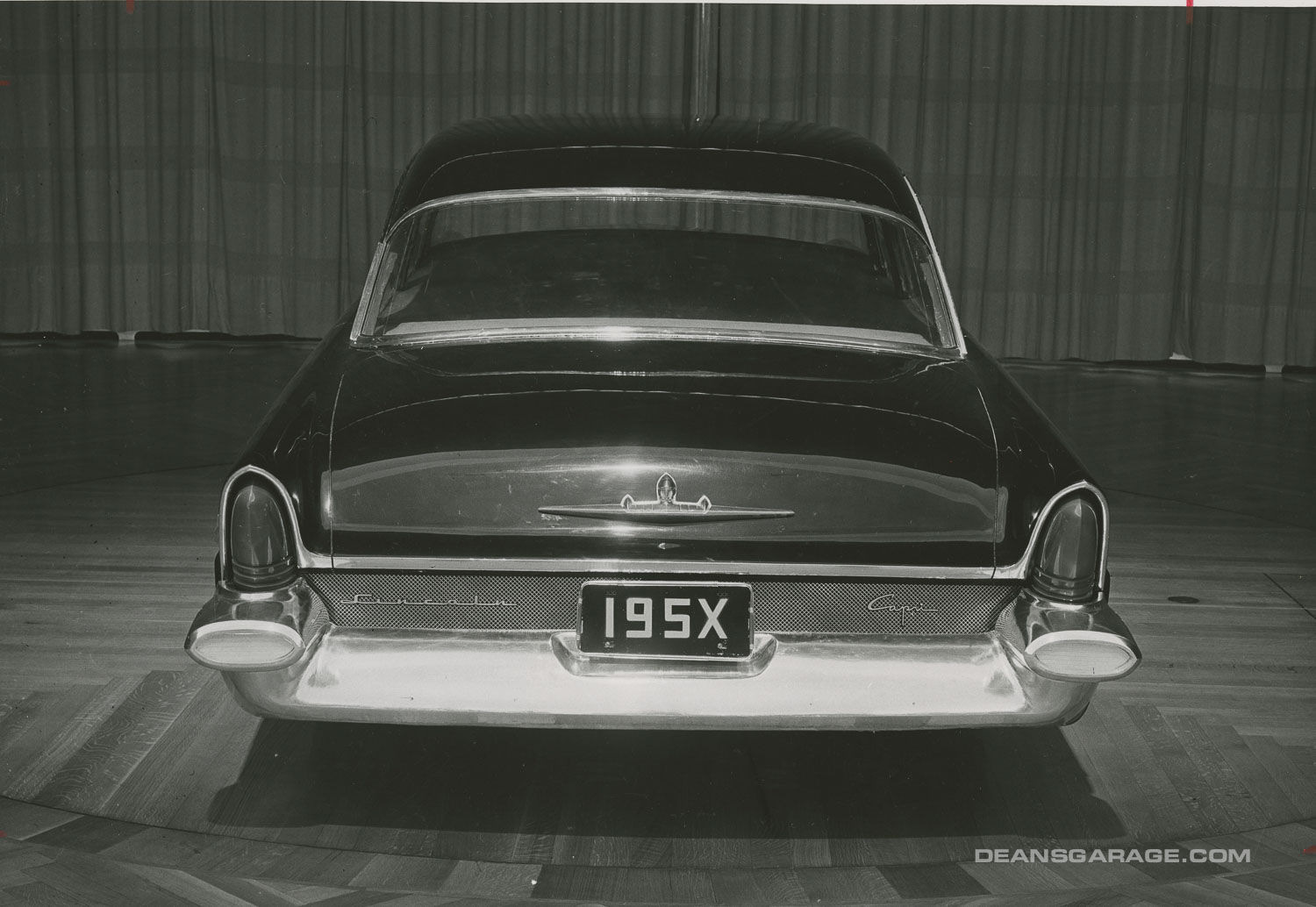

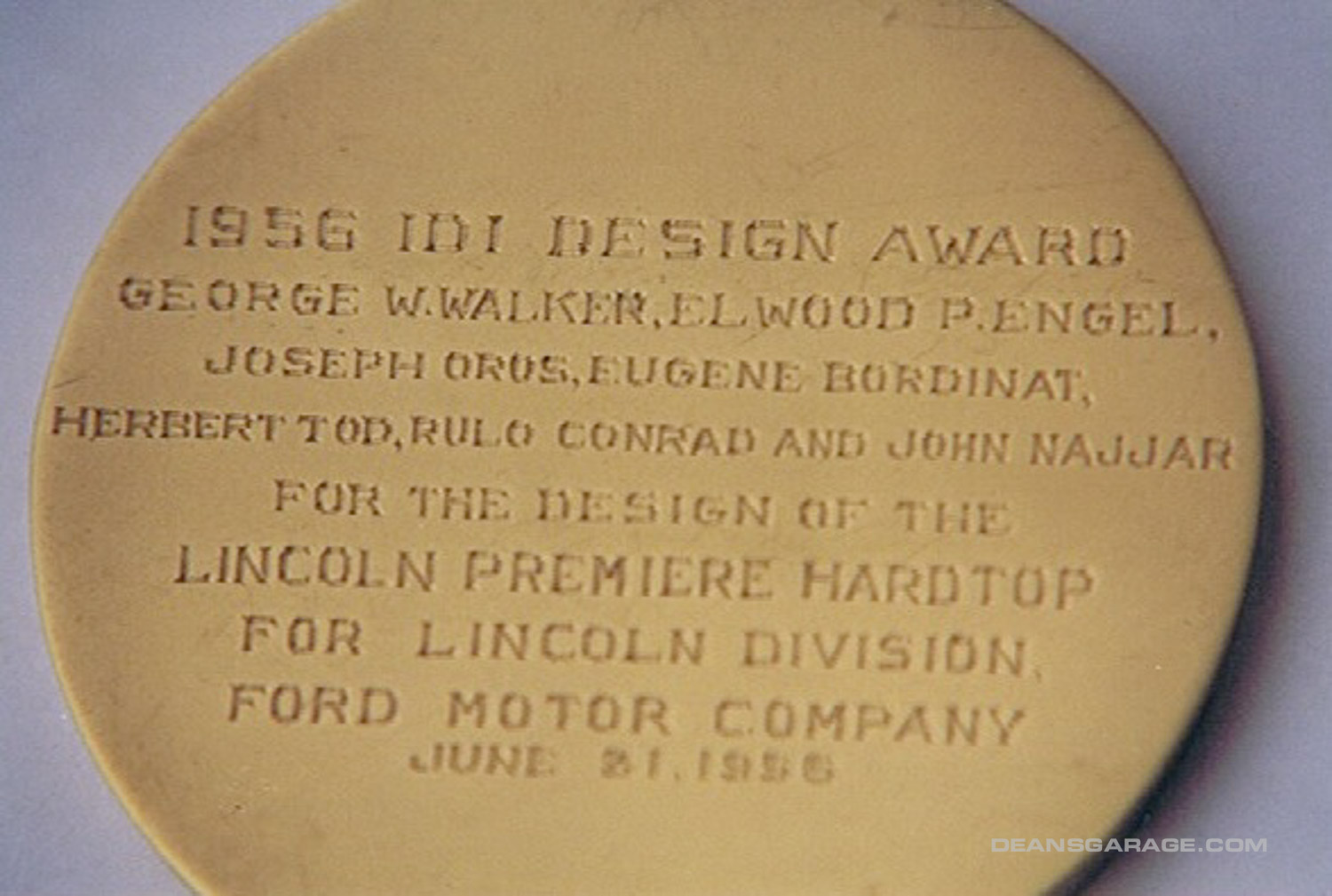

The new proposal was designed by Schmidt, Herb Tod, Rulo Conrad, Don DeLaRossa, John Najjar and Joe Achor. Schmidt said the front of the ’56 Lincoln was based on the XL-500, a concept car he had previously designed. Clay modelers who most consistently worked on the car were Bill Leverenz and Gil Treweek. According to Schmidt, it was designed and clay modeled in secret—at least a secret from MacPherson who first saw it after lunch at the April Product Planning Committee meeting.

MacPherson was not happy. His only real comeback was that his engineers had not designed brakes, engine, or other running gear for a car so much larger than expected. The end result was that it was decided to give MacPherson’s engineers a year to update needed engineering. Thus, it was decided to introduce Schmidt’s new Lincoln as a 1956 model, not a 1955 model. Designers Gene Bordinat and Rulo Conrad were then directed to prepare a new proposal for the ’55 Lincoln based on the 1954 body and frame. That was done mainly by extending the back end of the ’54 Lincoln by eight inches. It may have been backwards, but the ’55 Lincoln was actually designed AFTER the ’56 Lincoln. Because Schmidt’s proposal had no interior to go with it, that was designed in Don Beyreis’ Lincoln interior studio by Stan Thorwaldson

After Schmidt’s larger Lincoln proposal was chosen, MacPherson didn’t make Schmidt’s life at Ford’s Design Department easy, and it finally lead to Schmidt’s decision to leave Ford in March 1955 for a better paying job running Packard’s design department. When he designed the car that became the ’56 Lincoln, Schmidt must have known it would put his job in jeopardy. It did, but in the end it was Ford’s loss. Schmidt’s leaving ford eventually led to a two-year job running Chrysler’s design organization while Virgil Exner was recovering from a heart attack. Unfortunately, Schmidt died of a heart attack far too young in February 1990 at the age of 63.

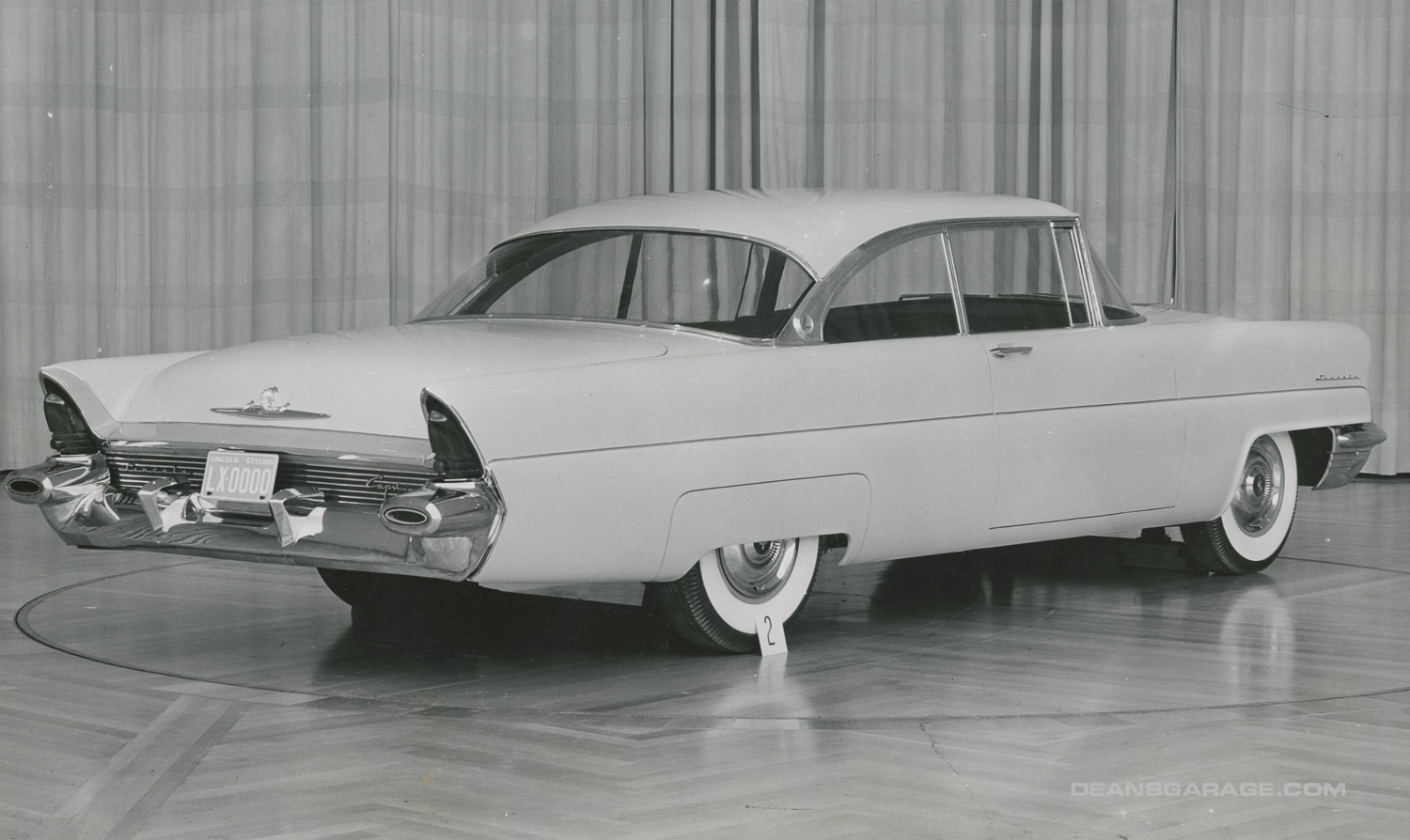

The ’56 Lincoln was the car that returned Lincoln to Cadillac’s class—and it almost doubled sales from the prior year. It was so much more successful than prior year Lincolns, that others rushed to take some credit for the car MacPherson did not want. Before 1953, design as a part of Engineering was in the same small building, so it must have been almost impossible to keep anything there secret. (MacPherson did travel a bit.) Schmidt claimed the car was designed behind screens in off-time. Later, assistant manager Bordinat claimed he, others and Schmidt were the designers responsible for the bigger ’56 Lincoln. That may be true. Clay modelers believed that Benson Ford, as head of Lincoln-Mercury Division, knew what was going on and that Breech also must have known of the ’56 Lincoln proposal before the April 1952 Product Planning Committee meeting. After the fact, MacPherson probably figured out who and how the end-run had been organized, but he never said one way or the other.

By May 1955, Henry Ford II and Breech decided that design should become a separate Ford department run by George Walker, who until then had been an outside consultant at Ford design. MacPherson’s objections got nowhere, but he was able to convince Ford and Breech that he needed a separate design department in his Engineering Department. Over Walker’s objection, that happened and several designers left to go with MacPherson. MacPherson had a major heart attack in 1957 and went into forced retirement. By that time Walker had gotten himself appointed to one of the committees that controlled the distribution of Ford’s development money, and was able to hamstring MacPherson’s separate design department. Walker also made fast friends with Ford’s new chief engineer.

Photos: Ford Design

Books by Jim and Cheryl Farrell

Ford Design Department—

Concepts & Showcars

1999, 10×13, 400 pages, Fully indexed

900 photos. Includes 150+ designers and sculptors, and highlights 100 concept cars.

ISBN 0-9672428-0-0

Lincoln Design Heritage:

Zephyr to LS (1936-2000)

2021, 10×13, 480 Pages, Fully Indexed

1,600 photos and illustrations

ISBN 978-0-9672428-1-1

The Ford book is $50 plus $7 S&H (US). The Lincoln book is $85 plus $10 S&H (US). Both books bought together are $110 plus $17 S&H (US). To order, email: cfarrell57@gmail.com

Think how things would have played out if the 1956 car had been built through the 1960 model year: it would have deep-sixed sales of Cadillac and Imperial to record lows.

If only hindsight would come first instead of last.

Thank you for revealing the rare, toxic story behind a most admired piece of art!

The small triangular C pillar really set the sedan apart. It was the perfect touch.

Jay S

So true. Ford stylists were at their peak during this period. The triangle was a better-than-nothing substitute for the lack of a 4-door hardtop, while still suggesting the elegance of one. Brilliant touch!