The Ford Mexico

By Jim and Cheryl Farrell

Most of us have seen the movie “Ford Versus Ferrari.” That movie may not be accurate in all respects, but it does show Henry Ford II’s willingness to spend Ford money to build cars that won races like the 24 Hours of LeMans. Fords won that race from 1966–69, but LeMans was not the first nor will it be the last time Ford went racing. In 1935, Ford-built race cars were driven in that year’s Indianapolis 500—with not very good results. Although Ford’s participation in the Mexican Road Races 17 years later was initiated by Benson Ford, HFII was well pleased when Lincoln won its class in that race in 1952, ’53 and ‘54.

In the 1950s, because of publicity about Corvette’s success during the Daytona Beach Speed Week, HFII decided to send a well prepared 2-passenger Thunderbird to Daytona Beach to compete. During a speed run, the Thunderbird hit a bump, took to the air at a reported 135 mph, went upside down, and then slid down the beach for about 1,500 feet. Much to HFII’s embarrassment, the wreck was all captured on camera.

Because nobody could tell HFII what went wrong or how to fix the problem with the new Thunderbird, he contacted Ford engineers and asked them. His engineers had no answer either, but they referred him to Ford’s resident aerodynamics expert, Alex Tremulis, at the Ford Styling Center.

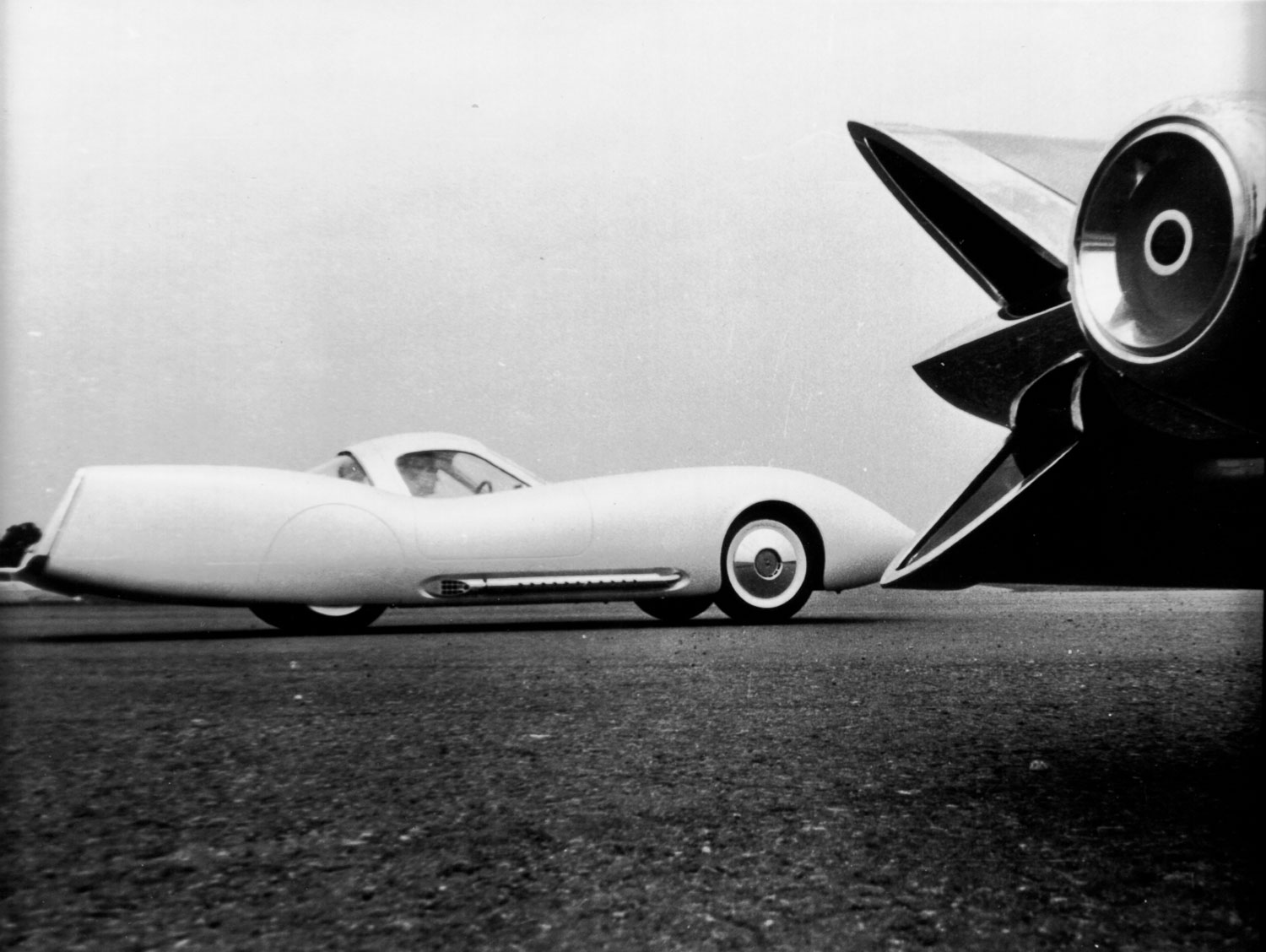

Tremulis, who was head of the Advanced studio at the time, told Mr. Ford that the problem was obvious—the Thunderbird developed too much lift over the rear end, and when it hit a bump it went airborne. HFII asked Tremulis how to fix the problem. Tremulis told him it couldn’t be fixed, and the next time the Thunderbird was going that fast it was likely the same thing would happen if the car hit a bump. Tremulis then told Mr. Ford he needed a zero-lift car to fix the problem. Mr. Ford didn’t really know what Tremulis was talking about, but when Tremulis told him he could design such a car, HFII told him to please do so.

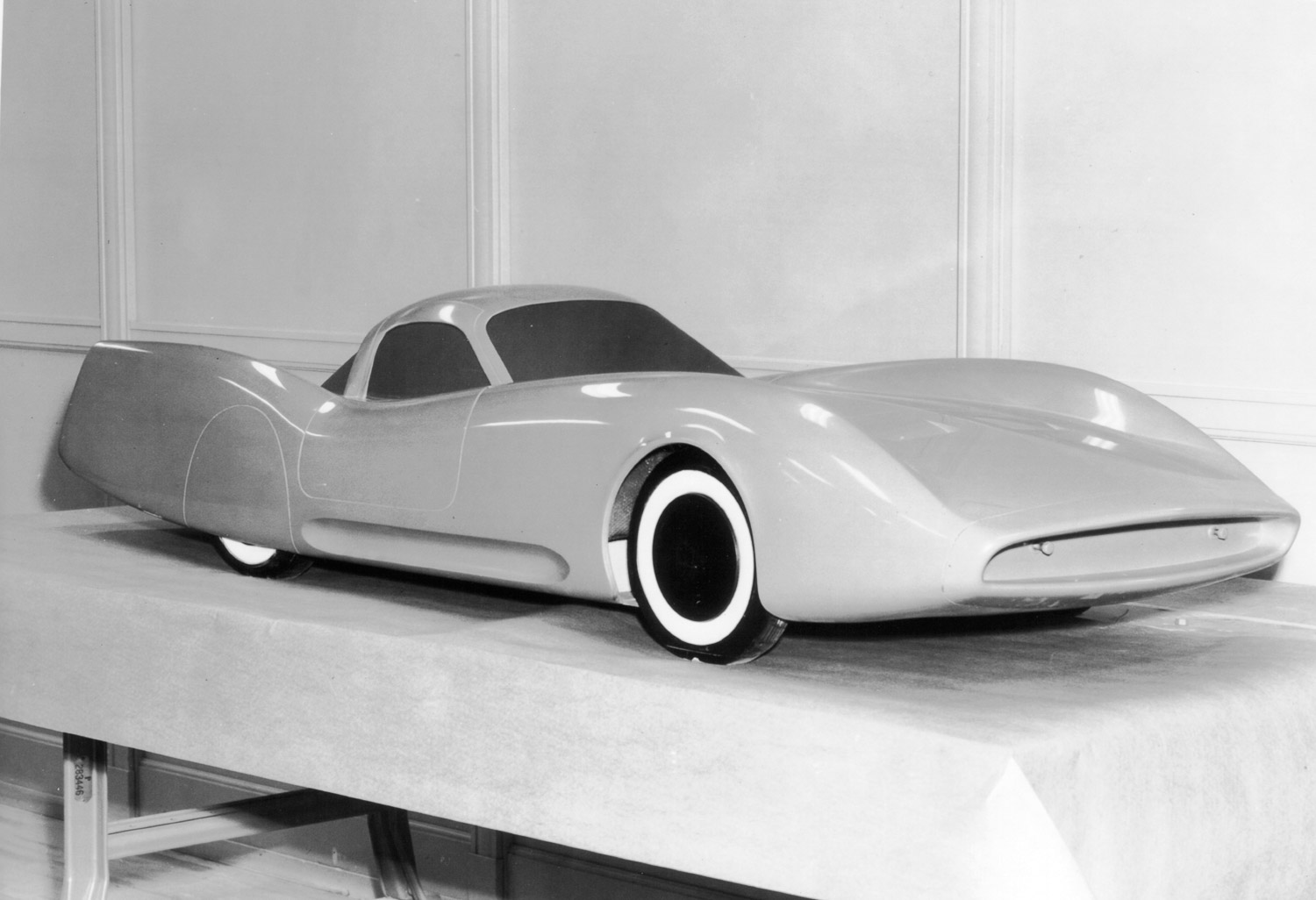

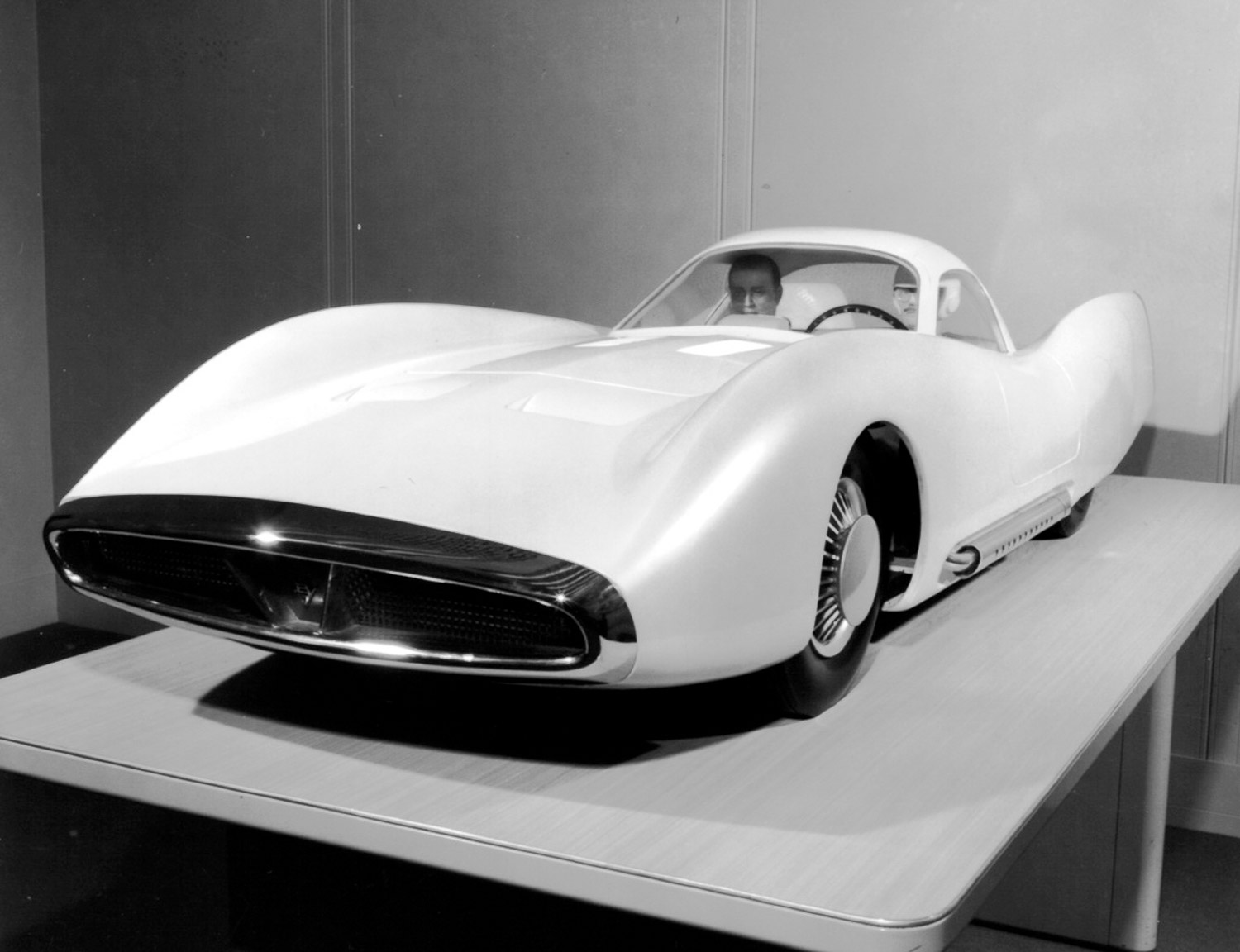

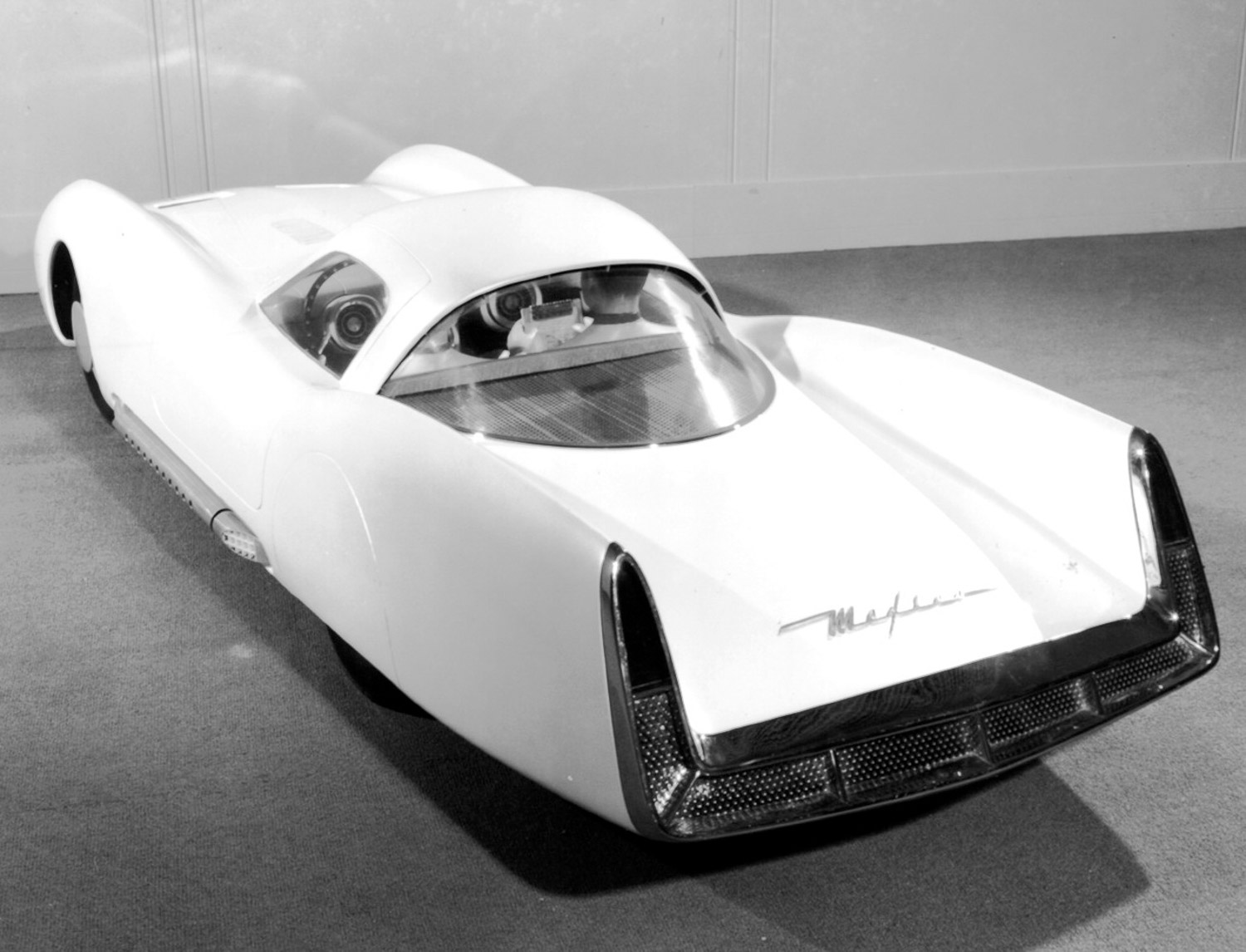

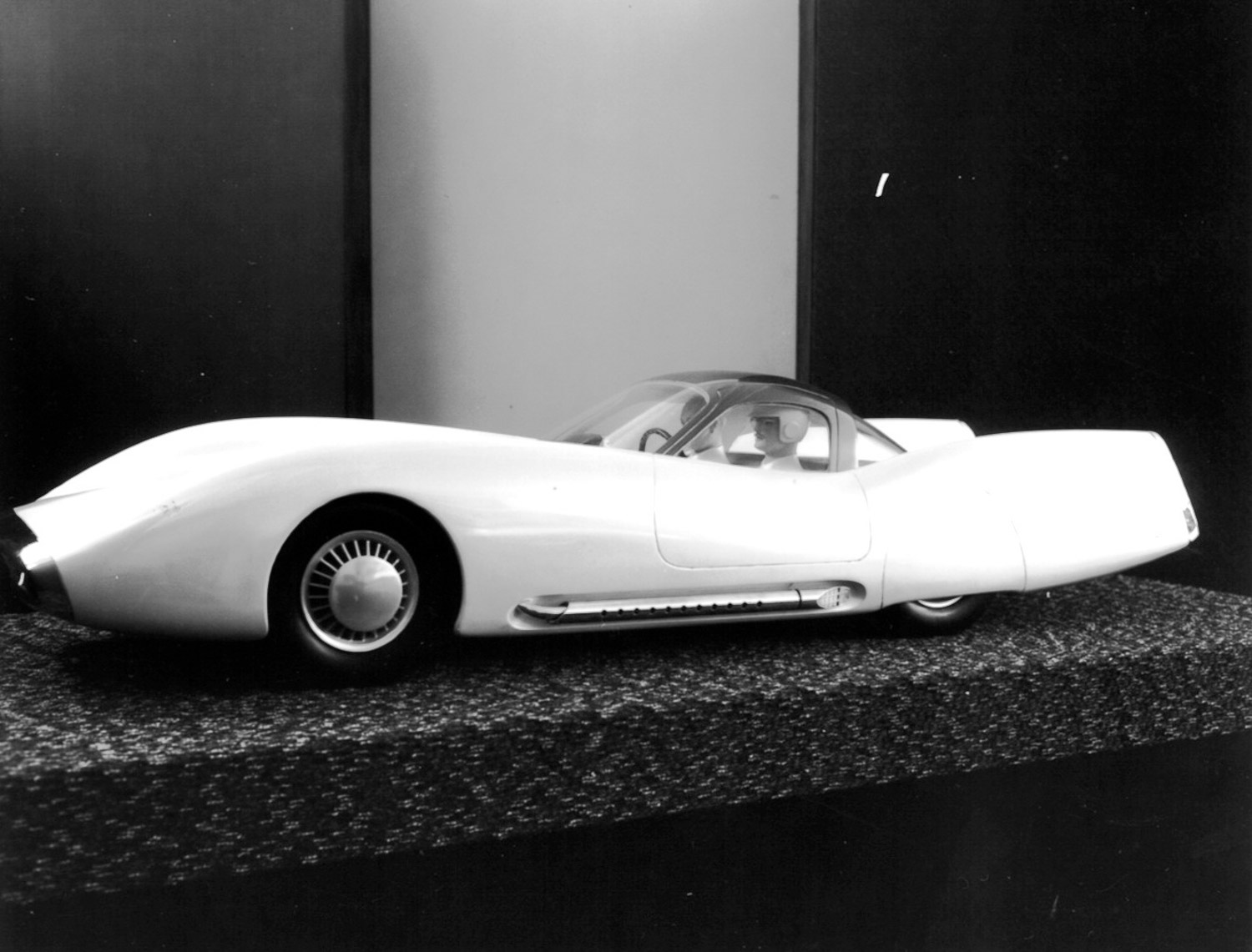

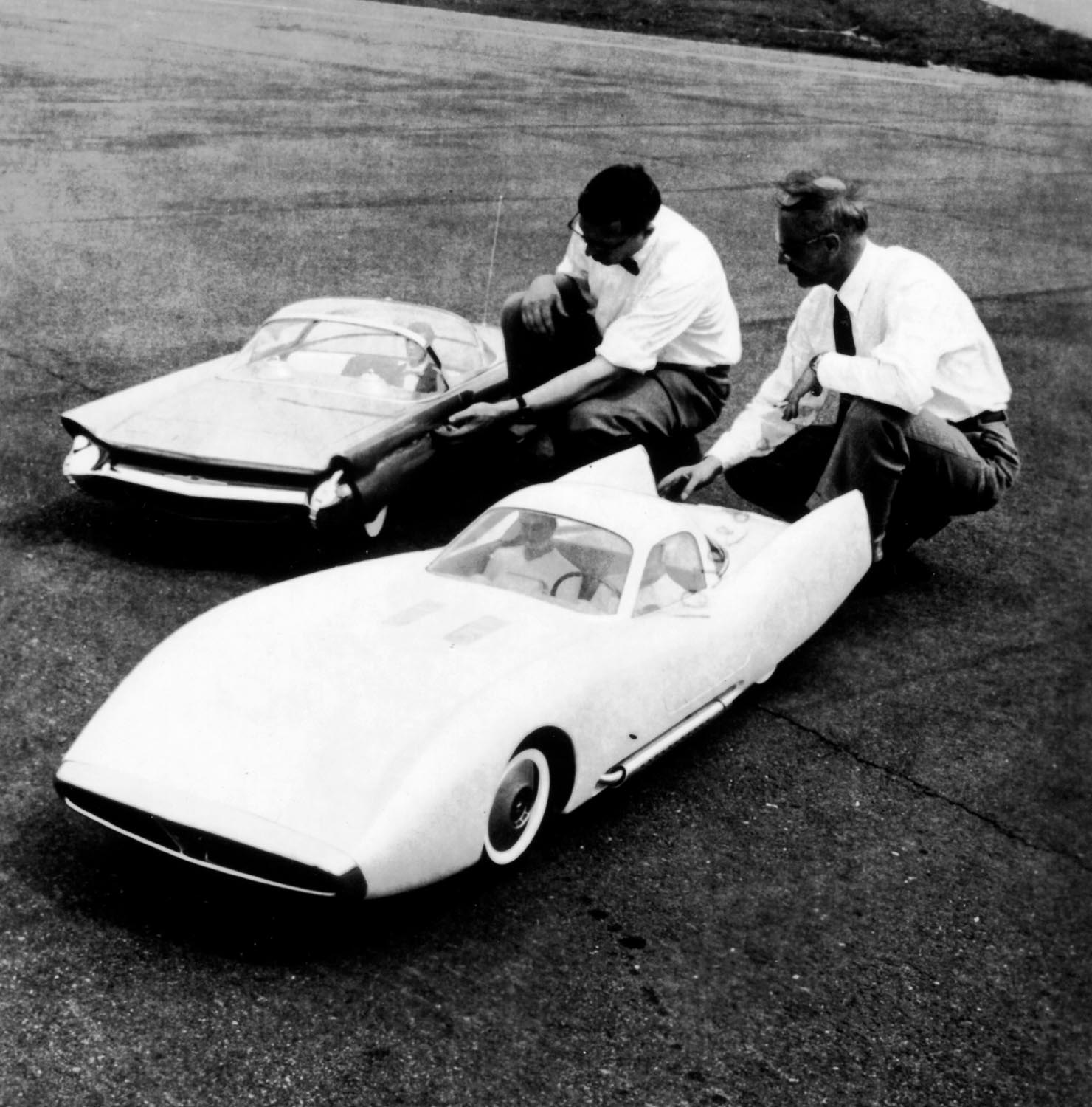

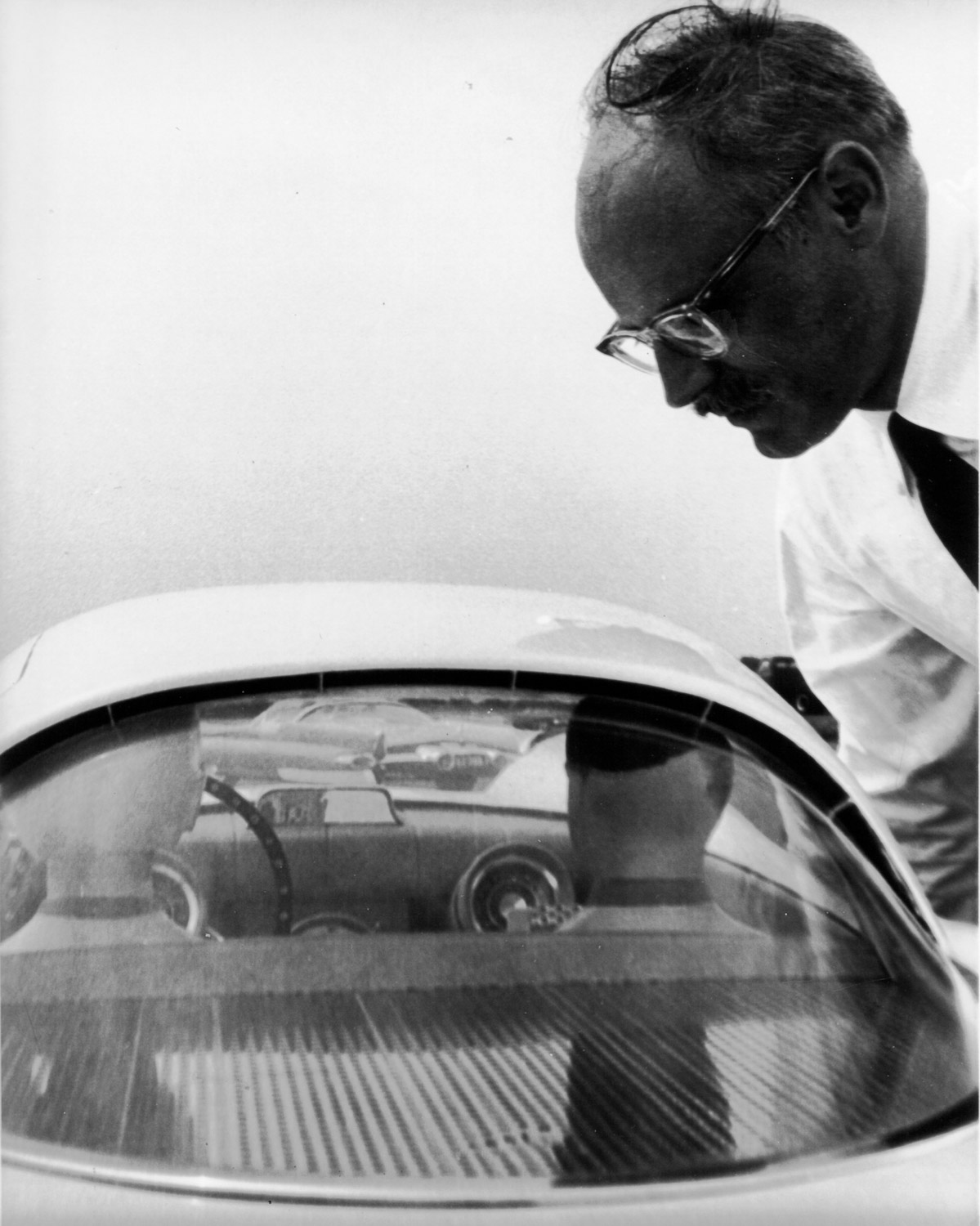

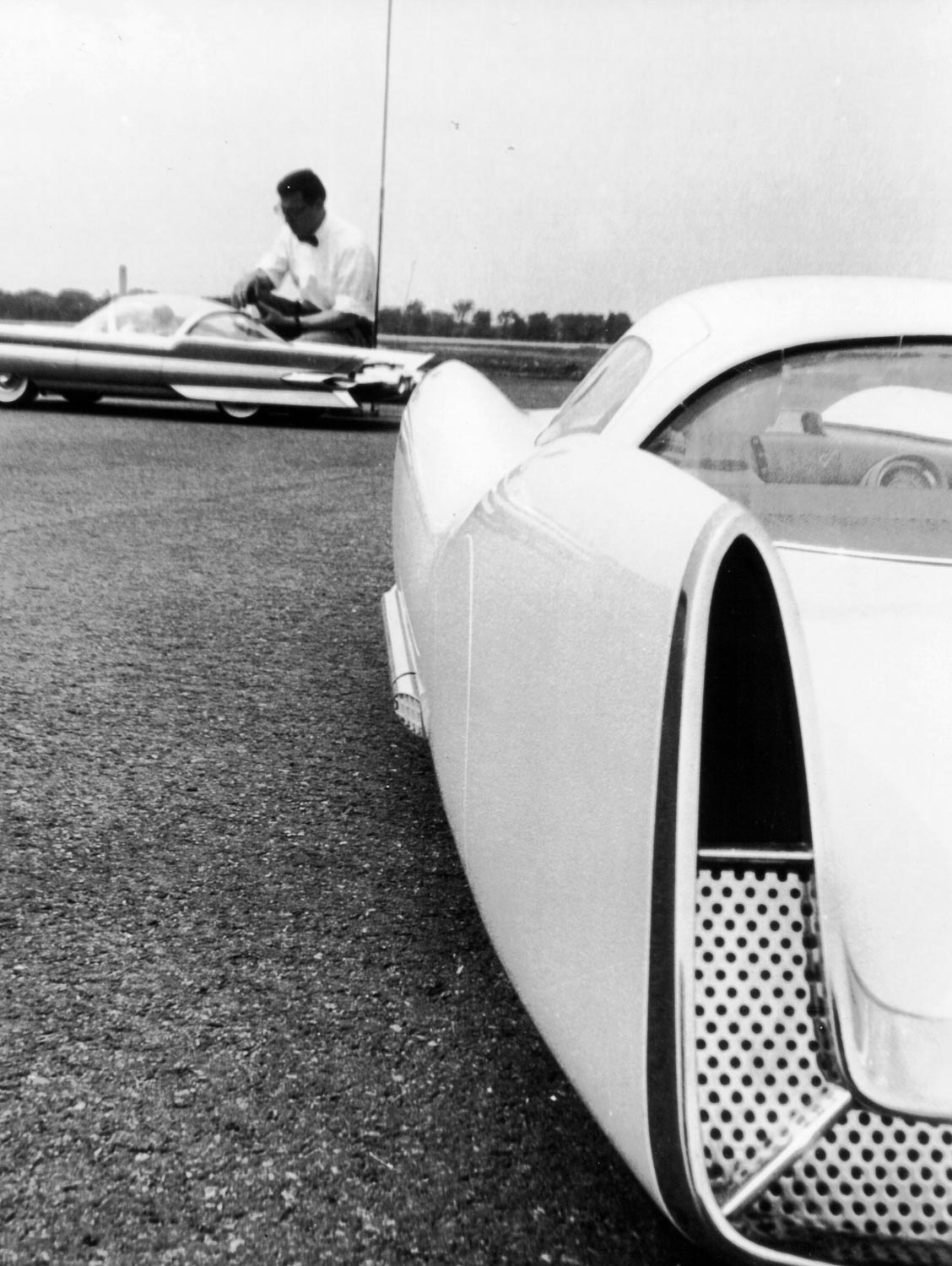

Management at the Ford Styling Center was skeptical, and Tremulis was given only one week to design his aerodynamic, zero-lift car. So within the next week, Tremulis, with assistance from designer Romeyn Hammond and clay modeler Larry Wilson, converted someone else’s already finished 3/8-sized model into a race car Tremulis named the Mexico after the Mexican Road Races.

After the Mexico was finished, Tremulis and Hammond installed a full belly pan. Most designer and engineers snickered, but Tremulis took the finished 3/8 model with belly pan to the University of Maryland’s wind tunnel where, to everyone surprise, it was determined to have a drag coefficient of .22 with the belly pan and double that without. When Tremulis returned to Dearborn, he told Mr Ford the result, and that he calculated the Mexico would have to be going 400 mph before it developed lift problems. As a result, HFII asked Tremulis to design a full-sized operable Mexico. The operable Mexico Tremulis designed had a tubular frame and weighed only 2,500 lbs, including a 400-hp Mercury Marauder engine. Tremulis told HFII the Mexico, as he had designed it with the Marauder engine, had a calculated top speed of 240 mph—fast enough to beat the world’s fastest sports cars.

In the 1954 Mexican Road Race, Lincoln won its class for the third year in a row, and plans were soon underway preparing for the 1955 race. The bigger ‘56 Lincoln was supposed to be introduced for the 1955 model year, but because of the need for updated engineering, including a bigger engine and brakes, it had to be delayed for one year. As a result, eight inches were added to the length of the ‘54 Lincoln body style, mostly in the rear end. With other changes, that car become the ‘55 Lincoln. The extra length may have helped it show continuity with the next (1956) Lincoln, but the extra length, mostly on the rear of the ‘55 Lincoln, created too much lift, which effectively disqualified it from consideration for future Mexican road races. That left Ford Motor Co. with two choices if they wanted to participate in the 1955 Mexican Road Race: 1) use Mercurys instead of Lincolns; and/or 2) enter one or more special-build Ford Mexicos in a different class and try to blow the doors off of every other car in the race!

The decision whether to prepare and enter Mercurys and/or to build and enter the Mexico in the 1955 race didn’t need to be made because future Mexican road races were cancelled after the 1954 race. (To many bystanders were being killed or injured).

Many designers and engineers at Ford in that era believed that had there been a Mexican Road Race in 1955, Ford could have built Tremulis’ Mexico in time and it would have won that race. In addition to competing in the Mexican Road Races, Ford designers and engineers dreamed of other races (like the 24 Hours of Le Mans); a 2,500 lb., 400-hp Ford Mexico could have been entered.

After it was decided not to build the Mexico as a real race car, Tremulis made a 3/8-sized driver to sit in the Mexico’s drivers seat. The little guy looked just like Tremulis with a racing helmet. Tremulis and Hammond also installed a platform under the Mexico with servos, battery and a radio-controlled electric motor. Tremulis often drove the Mexico inside and outside the Styling Center, sometimes just to see how far away it could be controlled. Both before and after Tremulis involuntarily left Ford in 1963, the Mexico usually sat on a raised bench near the door to the Advanced studio. Then one day, it was gone. A friend later told Tremulis that after he left, about 20 of his models were gathered up and moved to the Rouge, where they were put under a tarp—and years later were destroyed.

Photos: Ford Design

© DeansGarage.com, 2009–2022. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or the original copyright owner(s) is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to DeansGarage.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Books by Jim and Cheryl Farrell

Ford Design Department—

Concepts & Showcars

1999, 10×13, 400 pages, Fully indexed

900 photos. Includes 150+ designers and sculptors, and highlights 100 concept cars.

ISBN 0-9672428-0-0

Lincoln Design Heritage:

Zephyr to LS (1936-2000)

2021, 10×13, 480 Pages, Fully Indexed

1,600 photos and illustrations

ISBN 978-0-9672428-1-1

The Ford book is $50 plus $7 S&H (US). The Lincoln book is $85 plus $10 S&H (US). Both books bought together are $110 plus $17 S&H (US). To order, email: cfarrell57@gmail.com

Coulda, woulda, didn’t. The story of so many forward-looking ideas, and too many of Tremulis’s, though that 240 mph stuff sounds like car-salesman level guff.

I am glad that it was never built . It would have been an American embarrassment

Here is the Ford Thunderbird crash at Daytona Beach.

http://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/CGObNSK82A4?rel=0