Fabulous shot of the Mike Spence/Phil Hill Chaparral 2F at La Source hairpin, Spa-Francorchamps, May ’67.

From Primotipo. Re-posted by permission.

The Chaparral’s automatic gearbox failed in the race that was ultimately won by the Ickx/Thompson/Rees Mirage M1 Ford. 1967 was the last year of the 7-litre monsters; the CSI mandated a 5-litre limit from ’68.

Ford started the ’67 season with their new Ford GT Mk IV and then left the scene having won Le Mans twice on the trot—mission accomplished in a sense. Ferrari won the championship from Porsche by two points in a season of grids comprising Ferrari P3/4, Porsche 910, Lola T70, Ford GT40s, Alfa Romeo T33 , Mirage M1 and Matra M630—truly a Sports Car Season to savor.

The 2F was consistently quick throughout the season but often the transmission main drive-bearing failed. Both Hill and Spence were popular Chaparral team members. Of Hill, Jim Hall said “Phil was a great guy with a lot of talent and really fun to work with because he understood a lot of what was going on.’

“I think he was probably as good as anybody at making the car finish. He’d put many cars together himself and knew how everything was made and how to take care of it. He was a great endurance driver for other reasons, but for that reason, too. When we got near the CanAm season in 1966 we decided we’d offer Phil a drive. He was a great guy to have on your team—he pulled for you and worked for you. And in the endurance races he was our man. I think Phil enjoyed driving for us, we just had a good relationship.”

Phil Hill never raced again after his ’67 Brands Six Hour victory, a great way to bow out after such a career of achievement. “It was absolutely satisfying to win that race at Brands Hatch. In retrospect there couldn’t be a better way to finish a career could there?” he said.

Hall also had great respect for Spence who was killed at Indianapolis in May 1968 in a Lotus 56. “I really thought a lot of Mike. He was an awfully talented driver, very quick and a smart guy who worked hard. He was a good fit for Chaparral too. It takes the right kind of person to be on your team who fits in with your people and how they work and Mike fitted us well and was a joy to work with.”

Designer/Driver/Engineer Jim Hall’s cars bristled with innovation—the winged, 7-litre Chevrolet engined, fiberglass monocoque, auto tranny Chaparrals thrilled European spectators and finally won a ’67 race, the Brands Hatch Six Hour event in July before returning to their Midland, Texas base and the U.S. CanAm Championship from whence they came.

Innovative Chaparral 2F

The 2F was a massive departure from previous Chaparrals even by their standards.

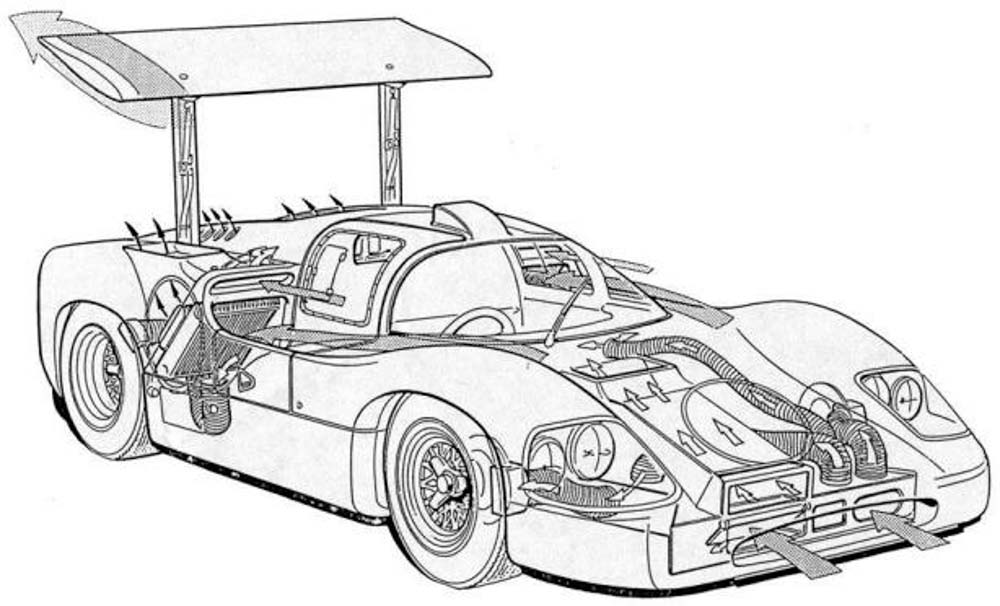

The car featured hip mounted radiators to better position weight and had the bi-product of keeping the cockpit cooler. The 5-year-old 2A chassis had special moldings bonded to it to create the square sided shape, and the transformations were such that they were effectively new. To provide strength to the bodywork, sections were laid up in female molds with 4-oz cloth and epoxy resin and ¼-in. PVC foam. In areas were strength wasn’t required the fiberglass was very thin. Firestone developed wider tires for ’67 which required wider bodywork. The actual chassis was covered by flat panels on either side. These were skins with empty space between them and the old chassis.

Externally only the central cab section looked the same. A new body profile was evolved in the form of a wedge to generate downforce. At the rear the body tapered away to a spindle shape with a chopped off tail.

To balance downforce at the front a similar type of high mounted wing as was used on the ’66 2E CanAm car was used, mounted directly to the rear uprights. The wing was connected to a foot pedal and via hydraulics allowed the driver to have feathered low drag or maximum downforce modes. Should anything go wrong with the feathering mechanism or the driver needed his left foot for the brakes, the car went to fail safe maximum downforce, understeer mode.

The front opening contained a spring-loaded flap or duct that opened against air pressure when speeds exceeded 120mph, this helped balance aerodynamic loads front to rear.

The body floated free on its springs devoid of practically any downforce which was applied directly to the uprights by the monster rear wing. As the nose of the car pitched forward more front downforce was generated, at 150 mph the nose compressed the front suspension, the trapdoor or flap opened progressively at 120–140mph, the car would then settle to its appropriate ride height front and rear.

Chaparral modeled both aluminum Chev 327 CID and 427 CID engines, with different car weight limits applicable under the regulations. They considered the existing CanAm aluminum chassis with 5-litre engine and a fibreglass chassis car with the bigger 7-litre lump. The 5.4-litre engine could have been destroked. Simulations showed the latest staggered valve porcupine 7-litre Chevrolet, cast in aluminum the faster option. It weighed only 85 lbs. more then the small block but gave around 100 bhp more. The engine used Weber style 58 IDM carburetors built by Chevrolet and gave around 575 bhp @ 7500 rpm.

The Chaparral’s GM automatic transaxle was upgraded to three speeds but the box was at its limits and the increased power and torque proved the gearbox was the packages weak link. This was feared by Chaparral from the start of the 2F program. GM simply did not want to build a new transmission and hoped internal changes could cope with the 7-litres greater torque, but this was not to be the case.

There is a lot of mystique about the transmission. Pete Lyons, in his Profile Publications article on the Chaparral Glassfibre Cars described it as follows: “It was laid out much like a Hewland with 2-and later 3-speeds and an hydraulic coupling, and a torque converter instead of a clutch.

The gears were simple straight cut spurs engaged by sliding dog clutches; every second dog was cut back a little to assist the clutchless changes. The changes were all done manually, the driver easing his throttle foot to unload the dogs and snatching the gear as quickly as he could. It therefore wasn’t really an automatic transmission; it was a fluid clutch transmission. The engine was always started with a gear engaged, the driver preventing a lunge forward by firm pressure with his left foot. At 5000 rpm the coupling was designed to lock up rigidly to prevent further slip and power loss. Sensitive drivers could feel this happening.”

The advantages of the ’box were better modulation of braking, on down changes the fluid coupling lessened any tendency of the rear wheels to lock, finally the fluid coupling absorbed many shock loads such as a ‘yump’ landing, common at the time.

Jim Hall’s attention to weight saving was fanatical. The car weighed 1750 lbs. wet, 600 lbs. less than the Ford Mk IV. This was because the fibreglass chassis, aluminum rather than Ford’s iron block engine. The batteries were of very expensive cadmium from the aerospace industry. The body was made of a sandwich of 1/4-inch thick PVC foam between the thin skins of 4-oz. cloth-impregnated with Shell epoxy resin which was formed to shape in a vacuum bag apparatus and then cured at room temperature. Sylvania made new quartz iodide lights using hand made bulbs in Marchal reflectors.

The whole car was built to exceptionally high aerospace standards of quality and finish.

Jim Hall and Aerodynamics

Gordon Kirby interviewed Jim Hall in 2008. He published these comments by Hall about his seminal aerodynamic work in the mid ’60s. “We calibrated the suspension by just rolling the car out and putting weights on it so we knew what load it took to move the car up and down. We had a cable drive that drove a pencil and a roll of paper that was run by a little motor so you could set your zero point. You would go out and make a run and push a button and make a mark across the paper so we knew what the front and rear downforce was. You could run a couple of different speeds and then you could put it on a graph. You knew that it was increasing as the square of the speed so you knew what the curve looked like and you pretty much had the downforce over a speed range. That was pretty simple to do.”

Hall’s method of measuring the air pressure or downforce on the surface of his car’s wings or bodywork was equally simple in concept. “The other thing we did was when we needed to change the surface we had a manometer that was just a bunch of U-tubes made out of Tygon tubing and full of colored water,” Hall related. “If you were in a sports car you put it in the seat beside you and then went out and tapped a bunch of holes in the. You ran these to one side of the tubes and ran the other one to a pitot tube so you could get the dynamic air pressure on the surface.

I originally did it with a Polaroid camera. I had a Polaroid camera mounted on the dash and the manometer mounted on the seat back beside me. I didn’t even have a pitot tube for a static pressure source. I read in a book somewhere that a guy in WWI thought about doing this. The way he thought about doing it was you took a thermos bottle and put a piece of tubing in it and right before you made the test you opened it up then closed it so you had static air pressure in it. Then you went out to make your run and compared it to the pressures you got, then opened it and made sure it didn’t change.

In a matter of about twenty minutes that thermos bottle would maintain an even enough temperature that the pressure wouldn’t change much. So you had some static pressure while you were sitting in the pit and you also had static pressure when you were going down the straightaway. It’s simple-minded, but pretty tricky! And that’s the way we started.

Then we bought a light airplane pitot tube and mounted it out front of the car. We found a static pressure place where we could run that pitot tube that matched the thermos. Then we had a static pressure source all the time.”

Thus began the serious science of racing car aerodynamics. Of course, Hall had no idea about the depth of the Pandora’s box he was opening but he is without doubt the father of the modern aerodynamically-driven racing car.

Chaparral 2F: Race History

One of the things which strikes you about this big car when you look at its speed during 1967 is its pace on all types of circuits, it was on pole at Monza, Spa, and the Nurburgring, and started from grid position two at Sebring and Le Mans, and grid position three at Brands.

The challenges of the Daytona bowl are vastly different to the swoops and curves of Targa or the ’Ring let alone the high speed challenge of Le Mans. It was clearly a complete car, an excellent all around package, the best car Phil Hill was quoted as saying that he ever drove.

At Daytona the car ran with its wing fixed in position, but still only just missed pole. Hill lead, took the fastest race lap and was pulling away from the Ferrari P4’s until the fourth hour, falling off on marbles after a pitstop and hitting a wall. Hill was a little miffed that teammate Mike Spence, with whom he had a great working relationship, had not warned him about the hazard, their race ended on lap 93, Bandini and Amon taking a Ferrari P4 win.

At Sebring, Hill was forced to retire from the meeting having acute appendicitis so Jim Hall stepped into the car with Spence. He was 2nd on the grid but had trouble starting. The car retired on lap 145 with differential failure, the car trailed smoke for several laps in advance of retirement, victory went to the Mclaren/Andretti Ford MkIV.

In Europe the cars were based in Frankfurt, the Monza event the first on the continent. Spence put the car on pole, using the second 2D chassis converted to 2F spec and from the flag diced with the P4’s but a universal joint failure eliminated the car before the end of the first hour. Bandini/Amon won in a P4.

At Spa a week later the car had a small trim tab added at the wings trailing edge, the tab made it easier to adjust the wings settings at high speed. Hill put the car on pole by 3.5 seconds but rain fell on Sunday, “Rainmaster” and local boy Jacky Ickx “ate us alive” Hill said. Spence ran in 5th until a fuel stop after which the car refused to start. At half distance it was 8th but another blown transmission seal caused its retirement. Ickx and Thomson won in a Mirage M1.

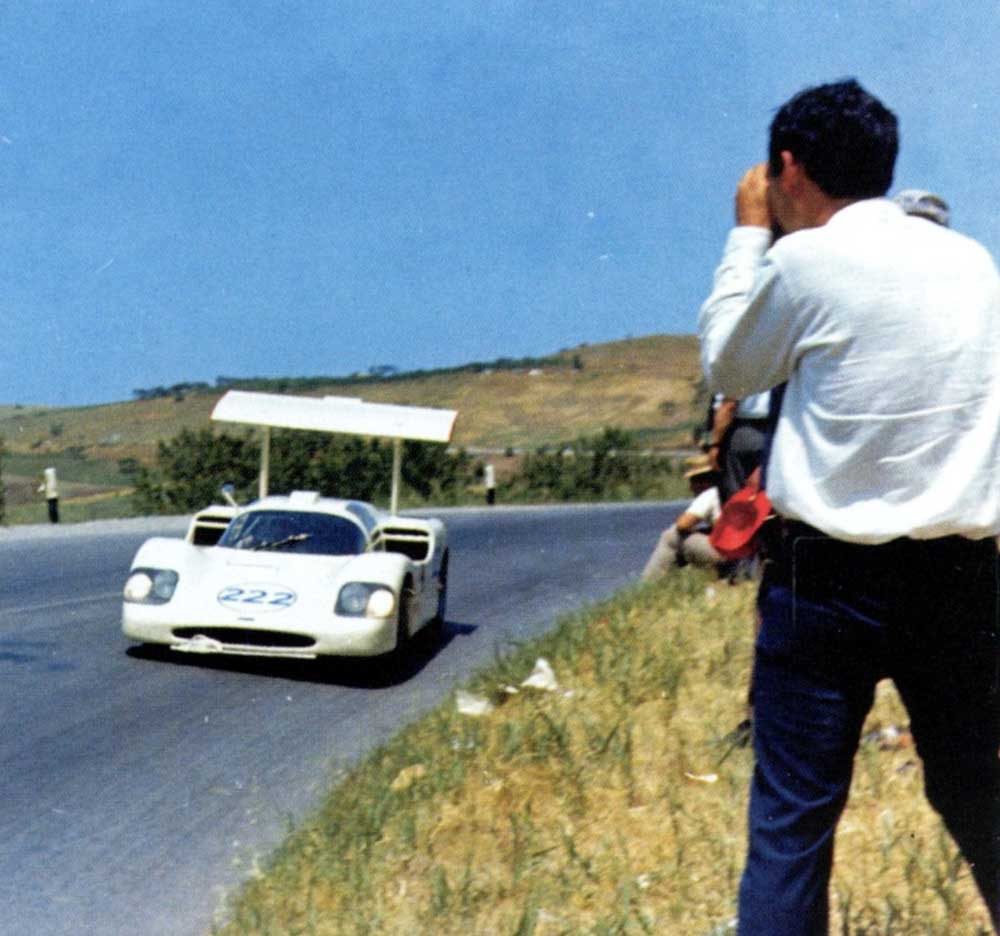

Mike Spence had other commitments so Hap Sharp stepped in with Phil Hill at the Little Madonie, the 575 bhp ‘roller skate’ a challenge around the mountainside of the famous Targa course. Local boy Nino Vaccarella was faster in practice than the 2F by 1.5 minutes. The car not entirely happy over the bumps but was still up to 4th, 9.5 minutes behind the leading Porsche when a tire went flat at Collesano. Paul Hawkins and Rolf Stommelen took the win in a factory Porsche 910.

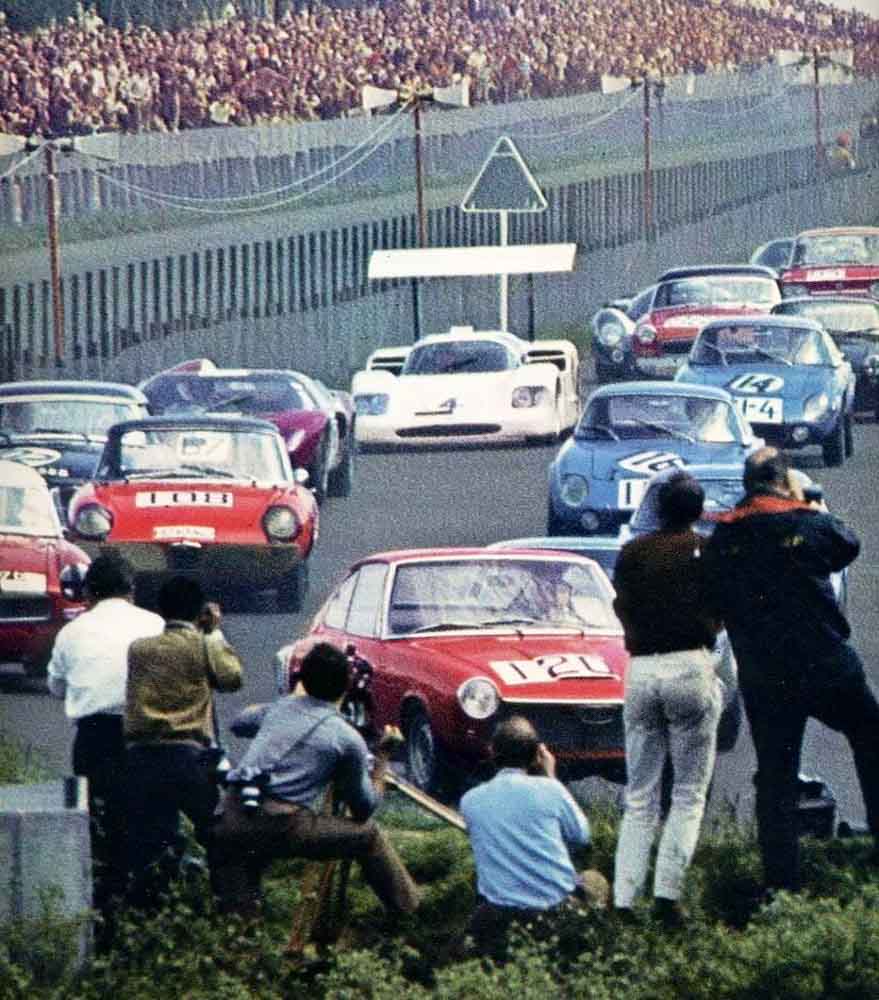

At the ’Ring Spence took 5 seconds from the old sportscar lap record and set the first over 100mph lap by a sporty, John Surtees was 7 seconds adrift in his Lola T70. Hill put on his harness after the Le Mans start so came around in 6th, by lap 8 he moved into the lead, but at about the 1.5 hour mark, on lap 10, the cars transmission again failed. Schutz/Buzzeta won in a Porsche 910.

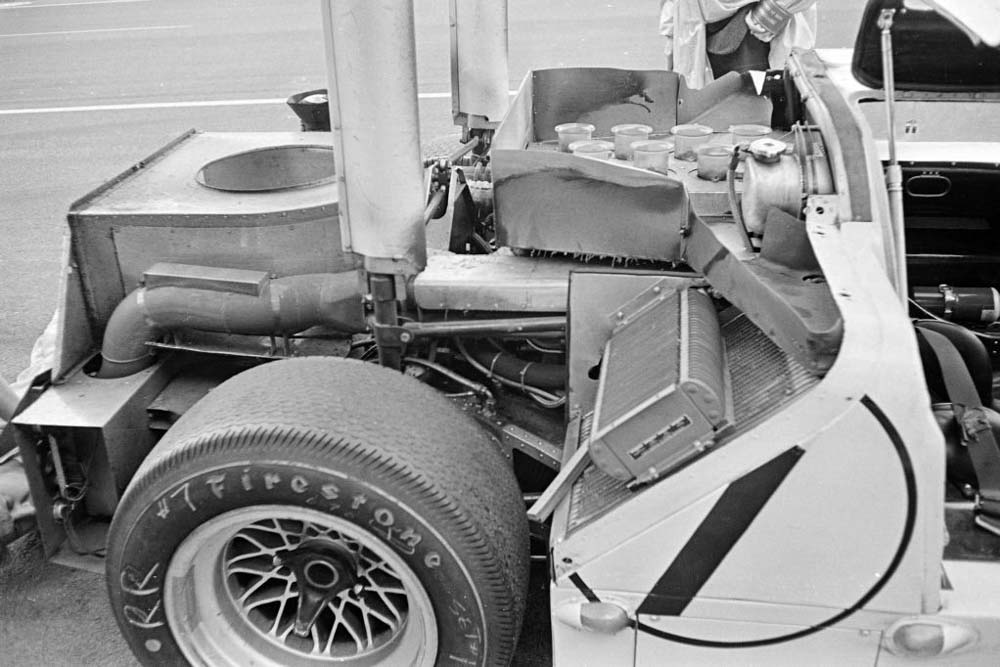

Le Mans was and still is all important. Two cars ran. Hill/Spence missing pole by only 0.3 of a second from a Ford Mk IV. Johnson/Jennings in the other car were 24th. Both 2Fs got away well, by the end of the first hour Spence was 4th and by the second he was 2nd, then the wing actuation broke, the car went into high downforce safe mode knocking around 40 mph off the top speed.

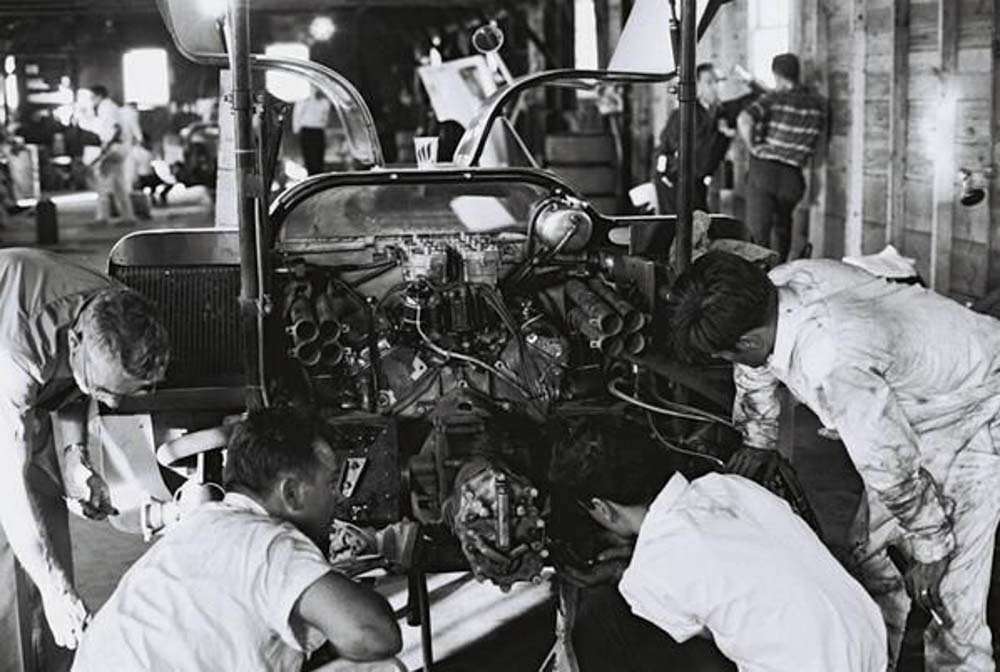

Inevitably the transmission gave trouble but the car was still in 3rd when an heroic three hour rebuild of the transmission was commenced by the crew, all to no avail as the car was withdrawn. The other 2F retired earlier with electrical failure. The race was famously won by the All American Boys, A.J. Foyt and Dan Gurney in a Ford MkIV.

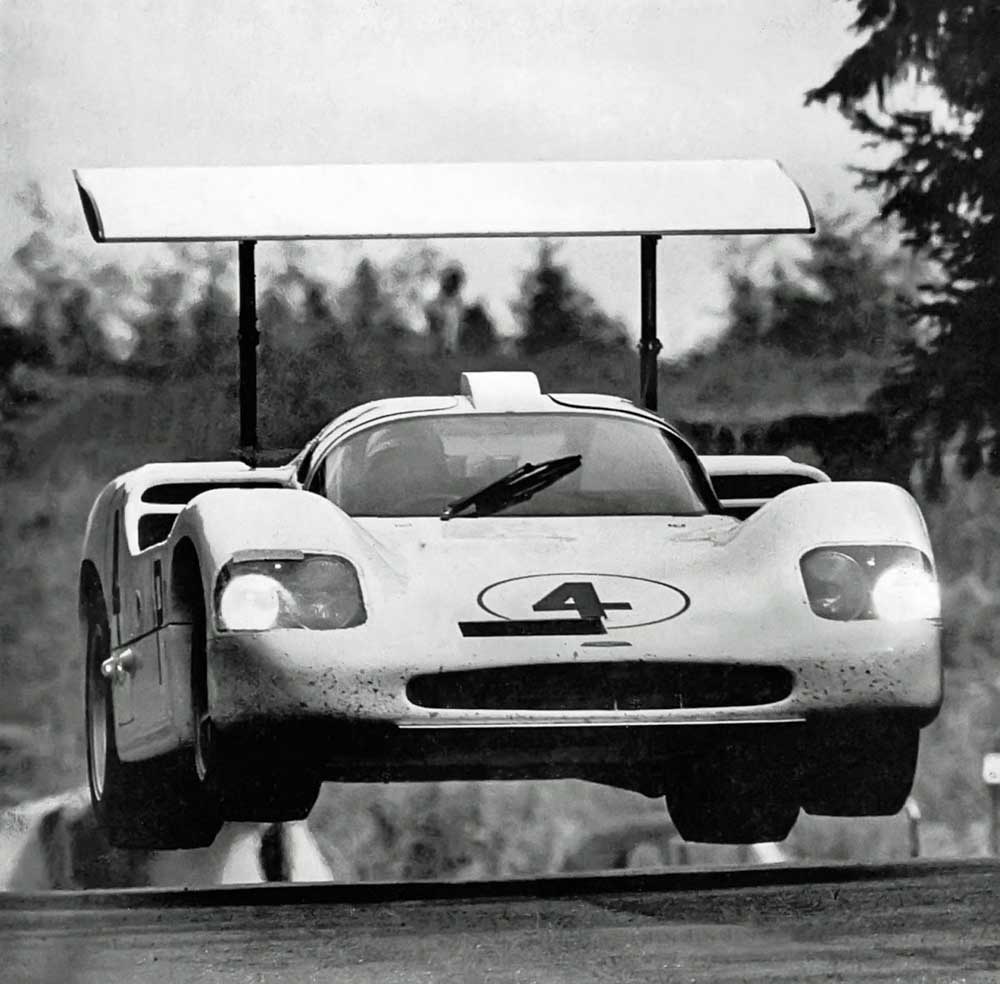

The inaugural Brands Hatch 500 Mile race was the last championship race of the season, the Brabham/Hulme Lola T70 on pole, Spence/Hill 0.8 second adrift in 3rd. Hulme took the lead but retired with rocker failure, letting the 2F into the lead. A long mid race pitstop dropped them back to 3rd but consistent laps of taking two seconds per lap from the Ferrari in front saw the wonderful car displace the Stewart/Amon Ferrari P4. A winner, finally!

Motor racing is full of ‘ifs, buts and maybes.’

One wonders what this seminal, defining, brilliant car would have achieved had the oh-so-clever automatic gearbox which was such a big part of most of the Chaparral 2 program, had the re-engineered gearbox it so badly needed and deserved.

In a sad sequel Jim Hall was preparing for another season with a 7-litre car for 1968 when the FIA announced a three litre limit for prototypes from 1968 and limited sports cars to 5-litres in capacity, 25 examples of which had to be built for homologation. The big Fords and Chaparrals were out, racing the poorer for it.

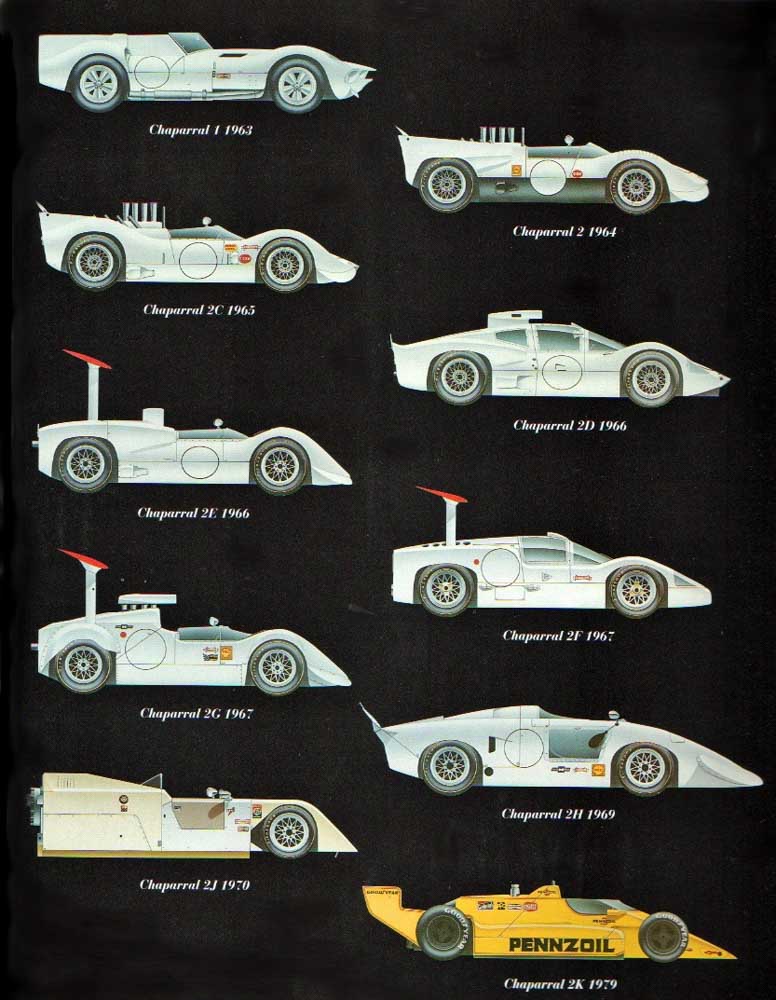

It was not over for Chaparral of course but after 1967 they focused on their domestic CanAm Championship with equally radical cars, and many years later a victorious assault on the Indy 500, both stories for another time.

Credits

Pete Lyons The Chaparral 2, 2D, 2F, The Glassfibre Series’ Profile Publications, Cutaway drawing—James Allington, Jim Hall quotes from a Gordon Kirby MotorSport articles in November 2008 and January 2011, Dave Friedman, Bill Wagenblatt Track Thoughts, Albert Bochroch, Nigel Smuckatelli, Karl Ludvigsen, Bernard Cahier, Louis Klemantaski.

See this link for some great information on Jim Halls fabulous cars.

As Mike Spence buckles up his seatbelt in the Chaparral 2F Chev, second on the grid, he is surrounded by FoMoCo vehicles; #1 the victorious Gurney/Foyt, #3 Bianchi/Andretti and Hulme/Ruby Mk4s, and the #5 Gardner/McCluskey and Schlesser/Ligier Mk2s, and not a Ferrari close by! (Unattributed)

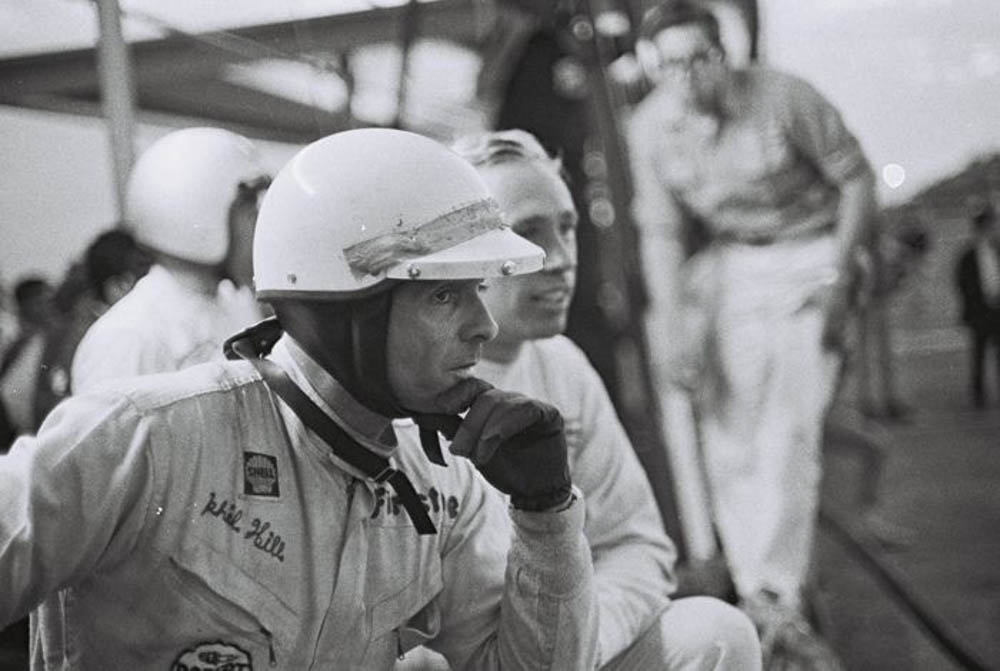

Phil Hill pondering 2F transmission dramas at Le Mans 1967. Mike Spence sans helmet behind him. (Dave Friedman)

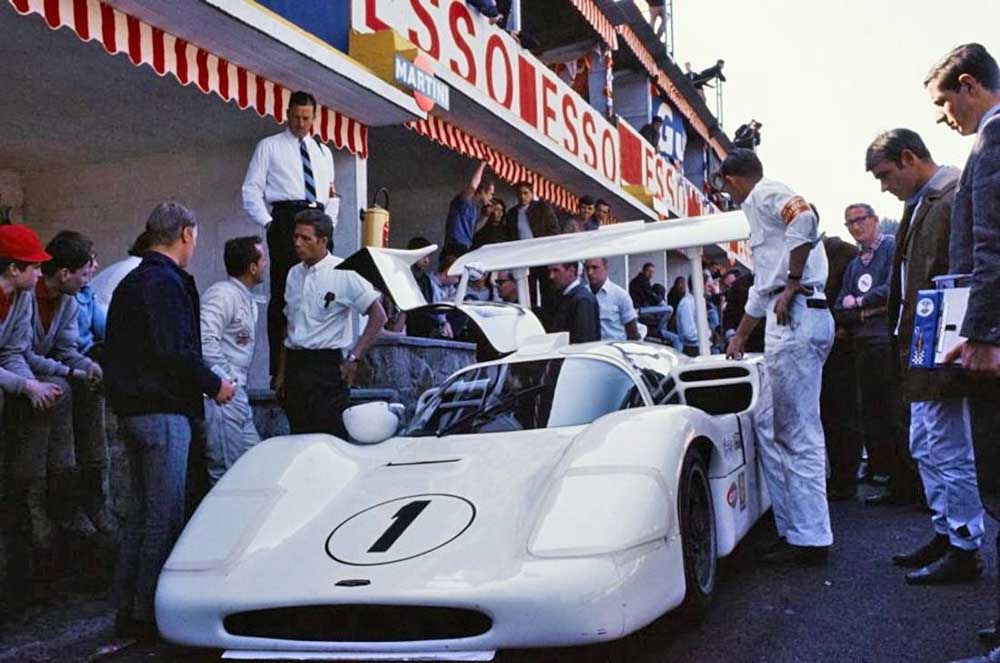

2F at rest, Spa pits 1967. Hill talks about set-up with Jim Hall. Note the front lip or splitter. Spence put the car on pole at 3:31:5, quick enough for 6th on the GP grid that June, in a car designed for 24 hour events. OK its 7-litres, but remarkable all the same. (Unattributed)

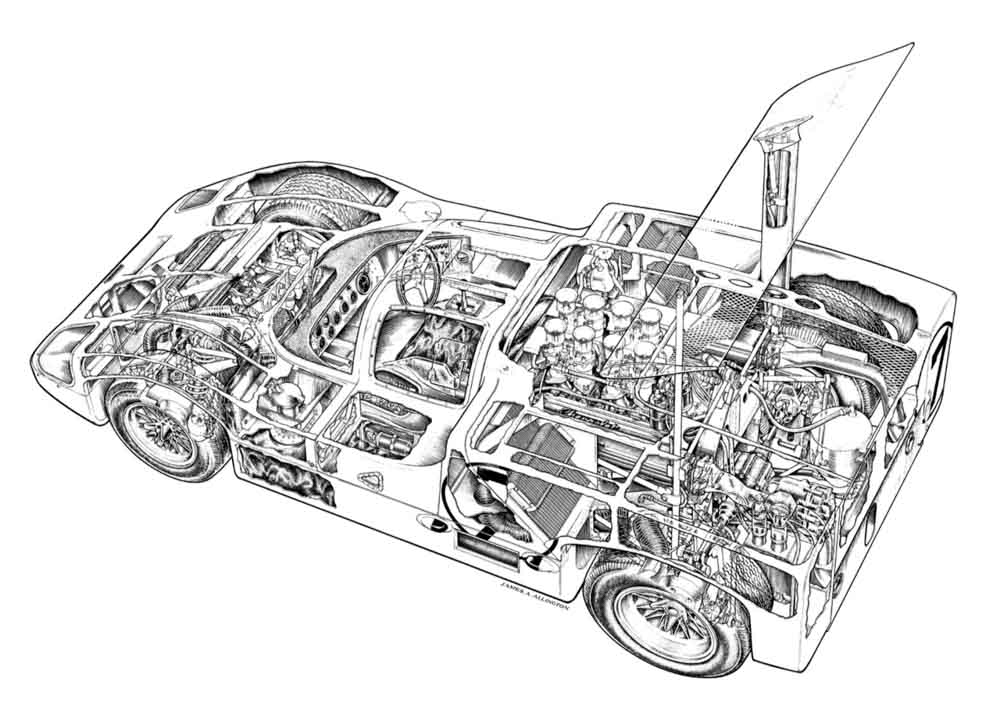

This drawing neatly shows the Chaparral 2F key aero elements. The car’s shape, front spring loaded flap, and you can just see the chin lip spoiler used on some tracks at the front. Rear mounted rads and beautiful ducting in and out and the movable high rear wing, to alter between download and neutral positions. (Unattributed)

The 2F exposed at LeMans for its transmission repair. Big wing and its mount direct to rear suspension uprights, note forward facing support strut. Mid mounted radiators, seat belt in the cockpit, radiator header tank, bell mouths of Chev/Weber carbs, spare wheel housing, exhaust ducting. LeMans number lights, 12 × 16 inch Chap alloys and big, wide Firestones. (Albert Bochroch)

Superb James Allington cutaway of the 2F showing all of its innovations: fibre-glass monocoque, wing, automatic transmission, 7-litre aluminum block Chevrolet. Simply superb innovative design and execution by Jim Hall and his Texas Team (James Allington)

Jim Hall in his 1967 CanAm challenger, the Chaparral 2G Chevrolet at Bridgehampton. DNF chassis failure. The McLaren M6 Chevs were dominant that year, Robin Herd, the M6 designer freely acknowledged the effect Halls’ designs, especially the 2E, the first car with the high wing had on him. Hulme won the race in his M6A. (Pete Lyons)

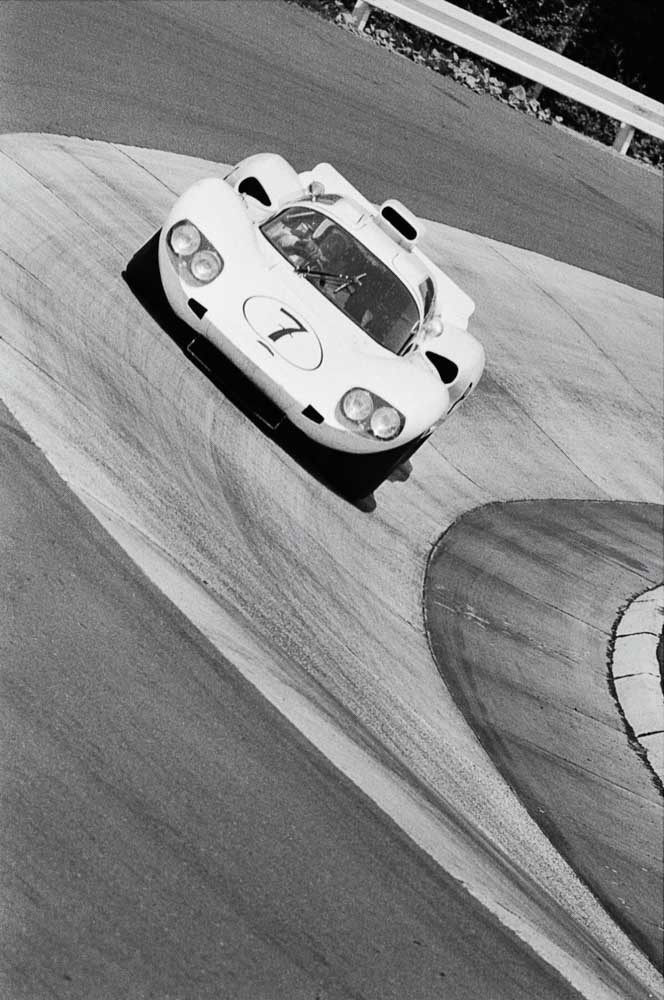

This overhead shot is of the 2F at Targa 1967, drivers Hill and Hap Sharp. The angle is interesting; you can see the contours of the car, radical for the time. Front flap exit above the number, mid-ships mounted rads and exit venting, the row of 3 circular vents in the rear panel to relieve air pressure and the ever present driver adjustable rear wing, max downforce for 90% of the time in Sicily, I imagine. (Unattributed

Chaparral 2F Chev in the Le Mans parc ferme. The radically different aerodynamic treatment in terms of both the cars shape and rear wing apparent. Road registered to boot. The car quailfied 2nd in the hands of Mike Spence and Phil Hill, they retired on lap 225 with transmission oil seal failure. The sister Jennings/Johnson 2F failed after 91 laps with starter and battery dramas. The race was won by the Gurney/Foyt Ford MkIV. (Unattributed)

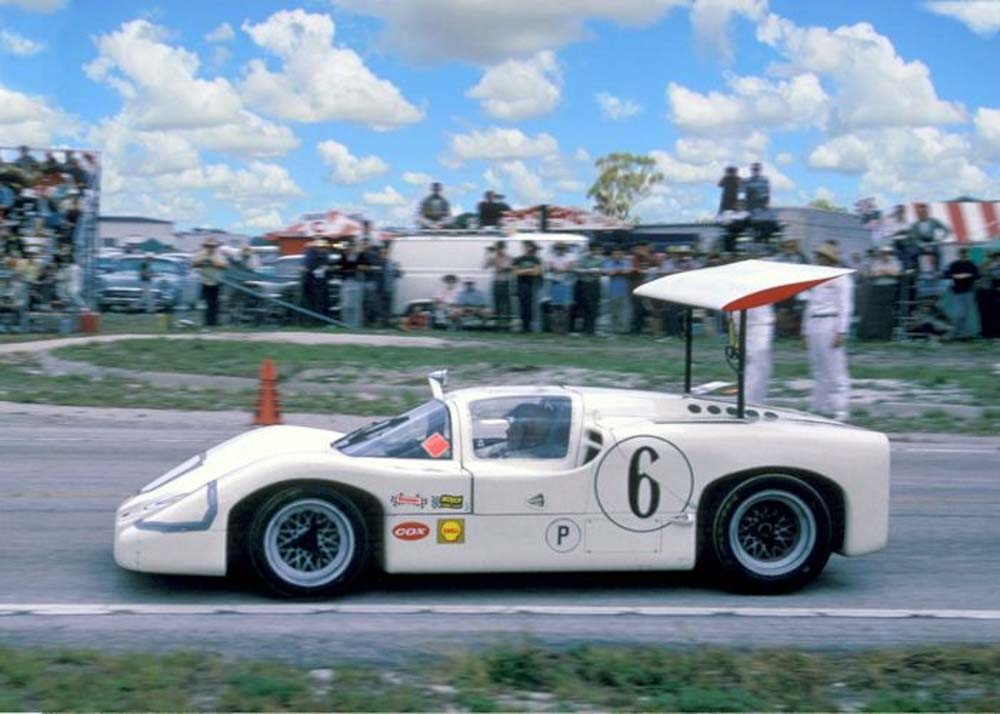

The 1967 Chaparral 2F’s predecessor in endurance racing was the 1966 2D, here in Jo Bonnier’s hands in the Karussel at the Nurburgring where he and Phil Hill won on the cars European debut. The 2D also used a fibreglass monocoque chassis, had a 2 rather than 3 speed box of the 2F and was powered by a Chev 327cid/5360cc ‘small block’ Chev giving circa 475 bhp @ 7000 rpm. Like the 2F, its race record was littered with DNF’s, 6 from 7 starts. (Unattributed)

Mike Spence here, and Jim Hall raced the 2F at Sebring. Fastest race lap but again DNF with ’box troubles. (Nigel Smuckatelli)

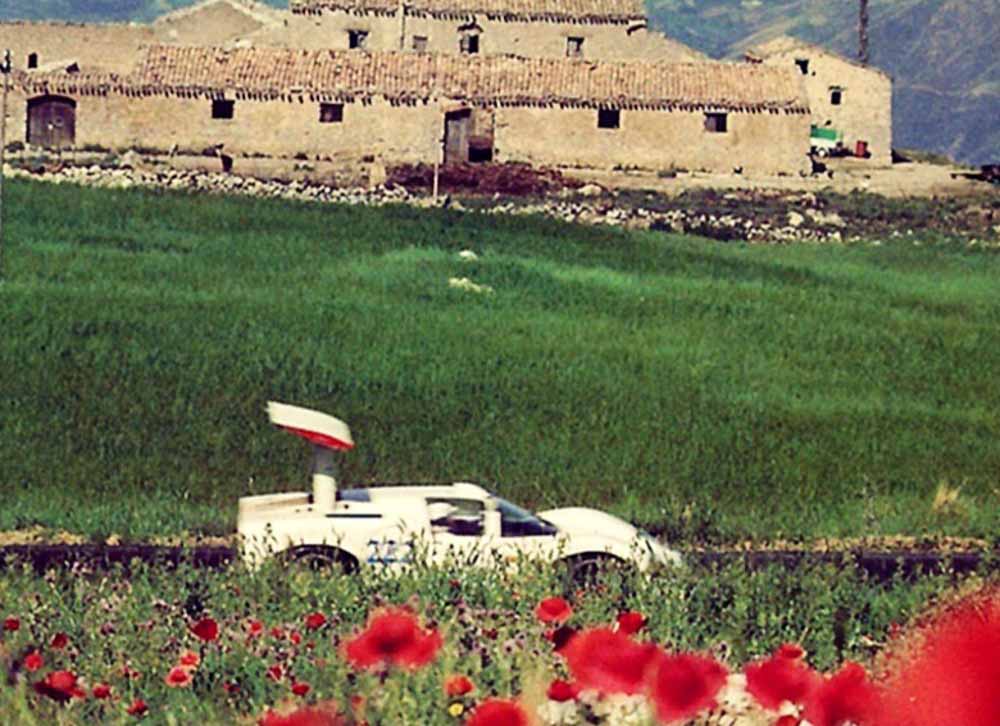

Phil Hill in his ‘outta this world’ futuristic Chaparral pictured with the ancient Sicilian landscape, and the oh-so-conventional, if gorgeous Ferrari P4’s for that matter. But Porsche prevailed, as they so often did at Targa. (Yves Debraine)

Lookout! Phlegmatic Siciliani, Targa 1967. Ride height up for this event, front splitter replete with an empty pasta packet clear. Phil Hill/ Hap Sharp Chap 2F. (Unattributed)

Phil Hill is back in the pack on lap 1 of the Nurburgring 1000Km, having carefully put on his ‘belt. Amongst the class cars are a Ford GT40 in front of him, you can also see the nose of the Surtees/David Hobbs Lola T-70 Mk. III Aston Martin behind and to the side, DNF with rear suspension failure. That wing will have given cars being pursued no doubt as to the car behind! (Automobile Year)

The long three hour, crowd pleasing, crowd appreciating transmission rebuild is underway. LeMans 1967. Franz Weis and Karl Schmid start the process by stripping the rear of the car to gain ’box access, no mean feat in itself given the careful integration of the overall package. (Karl Ludvigsen)

Mike Spence in the 2F at Brands Hatch heading for victory and running ahead of the factory Ferrari P4 of Ludovico Scarfiotti and Peter Sutcliffe, 5th. (Louis Klemantaski)

Its hard to know which of Jim Hall’s cars was the wildest. Perhaps the ’69 CanAm 2H, although unsuccessful. He doubled his bets with the 1970 2J, the famous ground effect sucker car being so quick officialdom banned it and with it the whole ethos that made the CanAm the great Formula Libre Series that it was. Here at Riverside CanAm race Vic Elford in the 2J Chev leads Peter Gethin in the championship winning McLaren M8D Chev. Hulme won the race in the other M8D, Gethin DNF engine on lap 21 and Elford DNF engine on lap2. (Unattributed)

Phil Hill and Jim Hall, CanAm, 1966. (Unattributed)

Sebring engine change showing the girth of the aluminum 7-litre ‘big block’ Chev and the housing of the famous GM ‘automatic’ transaxle. I wonder how long the change it took from start to finish? (Unattributed)

Targa, Chaparral 2F. Aero treatment of the car nicely contrasts with the Sicilian ‘roadies’. Wing in maximum downforce mode. Note the rear devoid of tail panel, compared with the earlier LeMans rear shot. (Bernard Cahier)

Phil Hill flying the 2F at the Nurburgring despite the Chaparral wing in full downforce mode! Lightening fast, the 1000Km another race the car should have won on a circuit one would not necessarily have thought it were suited. A versatile car the 2F, quick pretty much everywhere. (Unattributed)

Absolutely terrific story on some of the greatest racing cars of all time. Bravo Jim Hall!

More pictures in my book Chaparral – Racing Cars from Texas.

Boy, that front profile sure resembles the Porsche 956 that came later. Many aspects of this car’s design seem to have been used as inspiration for other Sports Racing Cars. Seems like the development budget wasn’t there though. Too bad GM didn’t pony up more and put some real might behind the effort. Things might have been different.

“ifs buts and maybes”… IF Mr Hall would have concentrated on racing alone as opposed to research / development and experimentation, there certainly would have been no ‘Bruce and Denny Show’ ; it would have been the Jim Hall Hour. Certainly not to make light of the talents of Mr McLaren and Hulme nor their crew, but the Chaparrals were in a class of their own.

Great photos – thanx for posting.

The real shame of all this – and of the entire 2F campaign – is pretty simple: they would’ve walked the field had Hall simply used manual transmission. Attempting a systems integration with all the innovative areas of the Chaparral at once was, sadly, a fool’s errand. Virtually everything else on the car worked just fine – except the transmission. Talk about a shoulda/woulda/coulda…..

The 2F was, more than once, fast enough in that season to qualify in the top 10 at a Formula One race, and I believe (Spa?) was fast enough for a front row spot. What a shame all that was wasted in pursuing the djinn of an automatic transmission.

I had bookmarked Deans Garage Chaparral section long ago but for whatever reason, I haven’t visited it recently. My loss. It’s always a joy to see the cars and the brains behind the cars that changes the face and history of racing.

I share Norman’s frustration about the 2F (I would love to have a street 2F sans wing!), but he is a bit off base. In the first place, the transaxle was manual, but it was clutchless. The fact that it was clutchless allowed the driver to control the articulated wing which was a main feature of the car.

Thankfully, the solution to the 2F’s tranny issues were solved for the BOAC 500 later that year. Chaparral continued to use the same tranny through the 2J (though certainly upgraded) which had MUCH more torque so the basic design was sound.

Jim and Chaparral were always on the bleeding edge of racecar development. Do we need to be reminded that when on the bleeding edge, you are more often susceptible to getting cut?

Thank you, Jim, for your great cars and the inspiration you were to thousands of hopeful and budding drivers and gearheads!