427 Mystery Motor Corvettes

Published by Hot Rod Archives, September 10, 2015, by David Kimble

Zora Arkus-Duntov’s high-performance engineering group was responsible for Corvette engineering and Chevrolet’s high-performance V8 development when the 348ci W-engine debuted for the 1958 model year. The solid-lifter version of the 348 with triple two-barrel Rochesters was rated at 315 hp (and was Chevrolet’s most powerful engine) while the Corvette’s fuel-injected, 283ci small-block was only rated at 290 hp. Duntov resisted putting the 348 into the Corvette, arguing its additional 100 pounds on the Vette’s front tires would compromise handling. By the time the second-generation Corvette Sting Ray came out for 1963, the W-engine had 409 ci and produced 425 hp with solid lifters and dual four-barrel Carters, but again, it wasn’t on the new Vette’s option list. Duntov didn’t feel the “fat block” 409 could pull its own weight. But there was a 427ci V8 on the horizon he would be happy with in a couple of years. Hot rodder Mickey Thompson, however, wasn’t going to wait.

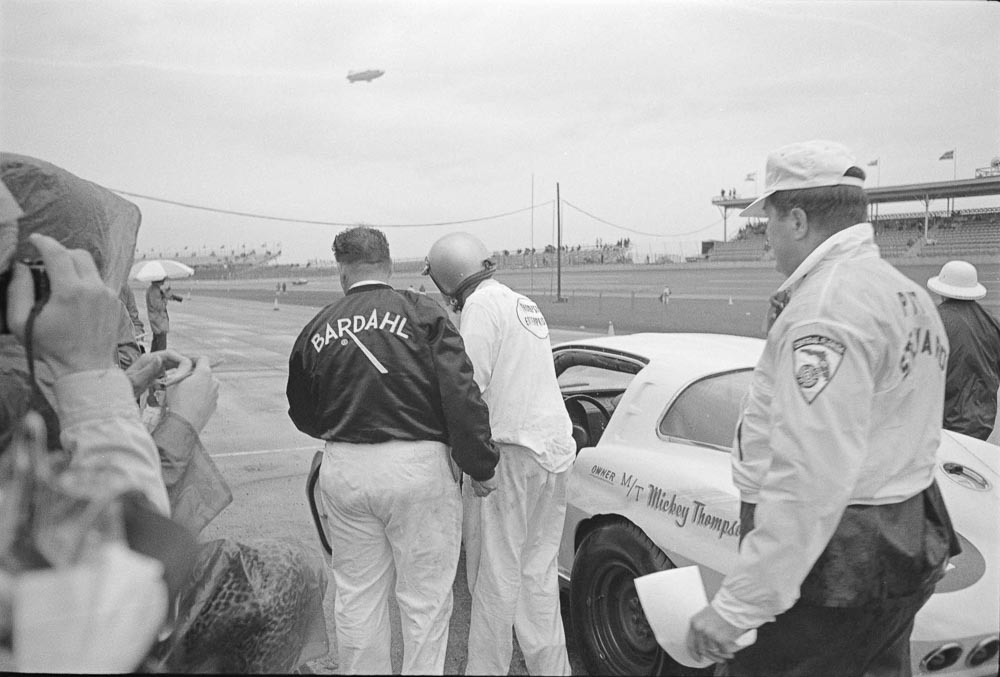

In 1962, Mickey Thompson was under contract with Chevrolet to campaign four Z06 Corvette Sting Rays in international GT endurance racing. As part of that program, the 34-year-old Californian had two of his Sting Rays equipped with 427ci Mark II-Stroked (MkIIS) big-block Mystery Motors. These big-block cars were prepared like NASCAR Grand National cars of the day by Smokey Yunick for the American Challenge Cup, a 250-mile GT sports car race on Daytona’s 2.5-mile tri-oval that took place on February 16, 1963—eight days before the Daytona 500 where most people think Chevy’s Mystery Motors debuted. You’ve never heard about any of this because General Motors had a corporate ban on racing in place when all of this happened. Fifty-two years later, as HOT ROD celebrates the 50th anniversary of the big-block Chevy, it’s time we tell you the whole story.

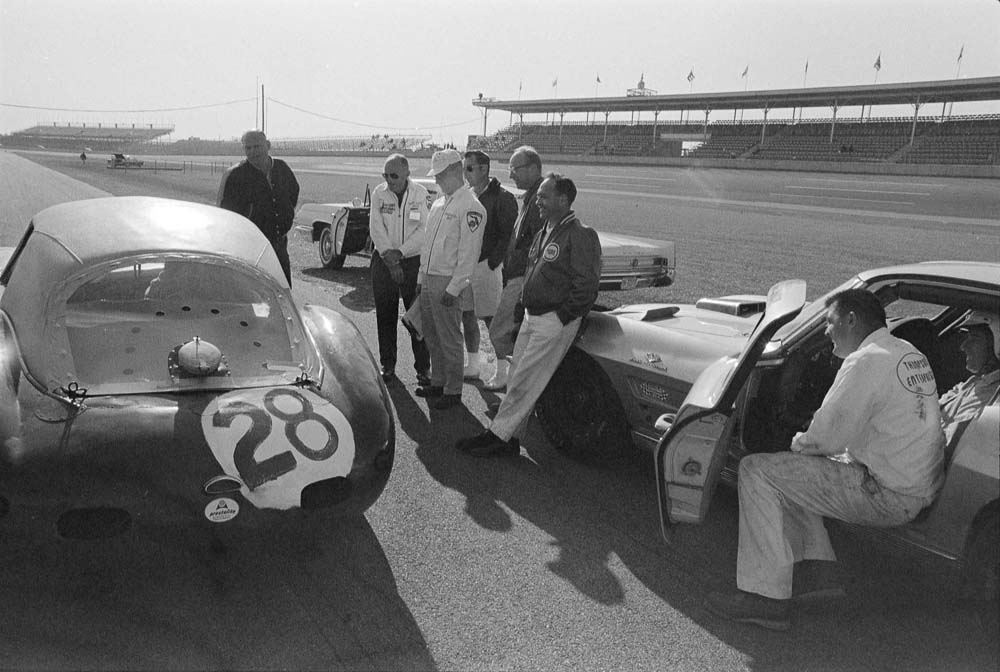

Mickey Thompson’s Mystery Motor Corvettes Mickey Thompson had helped Pontiac shake its stodgy 1950s image and become thought of as a GM performance brand, using a line of speed equipment and attention-grabbing cars like the Challenger I powered by four Pontiac V8s he drove more than 400 mph at the Bonneville Salt Flats in 1960. Thompson had been a Pontiac contractor, working directly for Semon Emil “Bunkie” Knudsen, who was Pontiac’s general manager at that time but was running Chevrolet by 1963. Thompson Enterprises was a front for Knudsen’s factory Corvette team. Knudsen also brought Smokey Yunick back to Chevy from his Pontiac NASCAR racing program. Yunick had won the second Daytona 500 for Knudsen with a 1960 Catalina he prepared, which was driven by Marvin Panch.

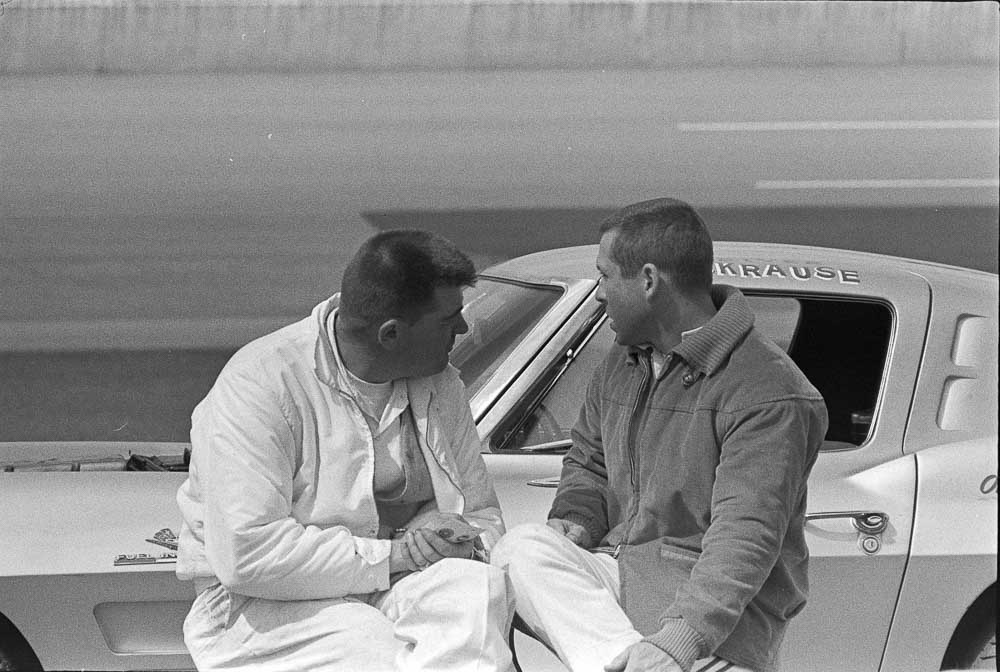

Mickey Thompson received a Daytona Blue Z06 Sting Ray prototype from Knudsen via airfreight in July 1962. It would be the first 1963 Corvette to ever win a race—the Los Angeles Times Three-Hour Invitational at Riverside, California, on October 13, 1962. Both the Shelby Cobra and new Corvette made their racing debuts that day; driver Bill Krause dominated the race in his Cobra until it broke a stub axle, and Doug Hooper (driving Thompson’s Z06) got the win.

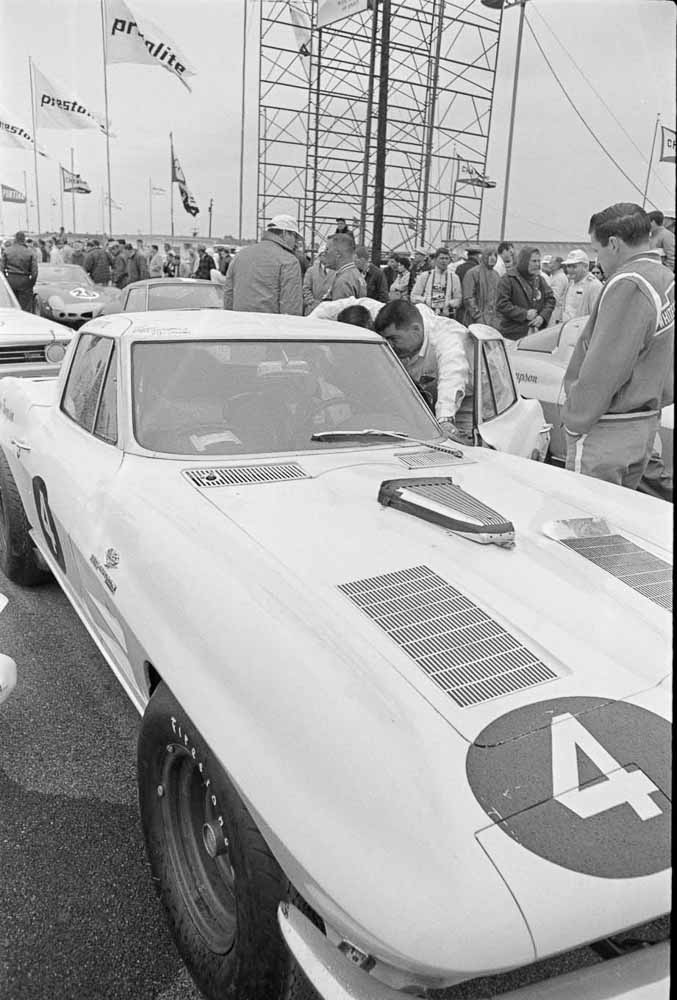

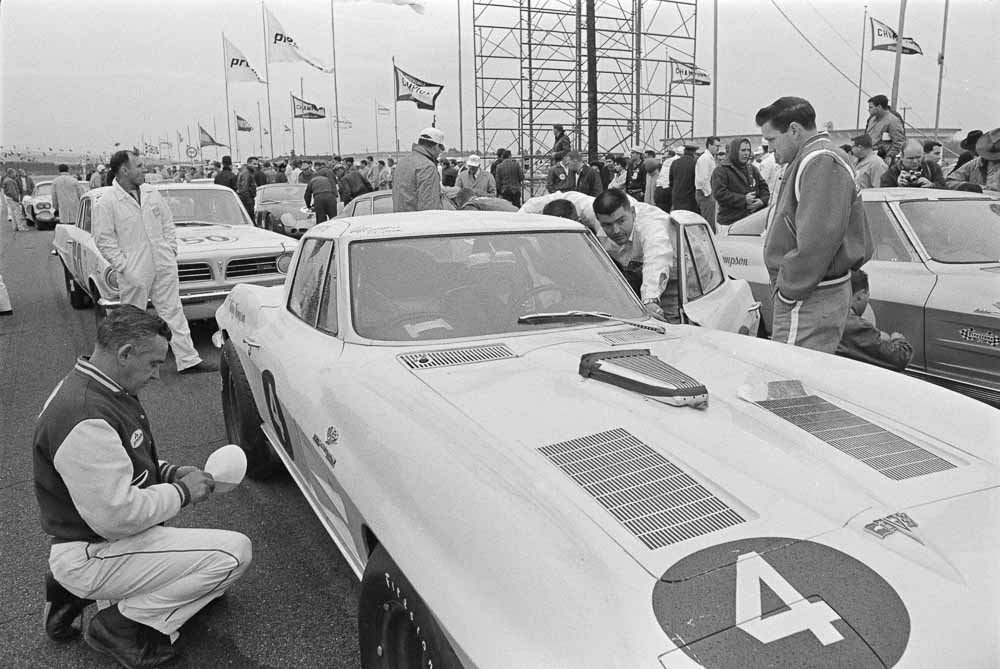

Technically, 1963 Corvette Z06 production began in October 1962, with six cars painted either Ermine White or Sebring Silver, and three of them were soon heading west from the St. Louis Corvette plant, driven by the men who were to race them at Riverside. Two others, one painted white and the other silver, were sent to the FIA’s New York office for homologation to make the Z06 Sting Rays eligible to compete as production cars. They were then shipped to Mickey Thompson’s shop in Long Beach, California. These cars were soon joined by two more Z06s, again Ermine White and Sebring Silver, for Thompson to drive on the street. The silver Corvette that had been inspected by the FIA went to Smokey Yunick’s “Best Damn Garage in Town” in Daytona Beach, Florida, where it was later joined by the white one, and both of them received rollcages, the 427ci MkIIS NASCAR Mystery Motors, and Saginaw three-speed transmissions that the Chevrolet Grand National cars ran on the oval tracks.

Yunick and his boys had the silver Z06 the longest and gave it the full NASCAR treatment, preparing it with Firestone Stock Car racing tires on reinforced steel wheels mounted on six-lug front truck hubs. They set up the front suspension with a straight antiroll bar that had splined actuator arms, spring rubbers, and two shocks per corner. The exhaust pipes were run inside the framerails and exited through the rocker panels just ahead of the rear wheels. Heat from the exhaust necessitated replacement of the rear portion of the fiberglass floor with an aluminum panel. The Sting Ray’s rear wheelwell openings were shaved to keep the oversized tires from rubbing when the springs compressed on the banking, and the Z06 36.5-gallon fiberglass fuel tank was replaced with a 50-gallon metal one for the 250-mile race. To save weight, a Plexiglas windshield, side, and rear windows were fit to the cars and magnesium rear axlehousings took the place of the stock cast-iron parts.

Despite its additional displacement, the MkIIS Mystery Motor was designed to fit into the same engine compartments as Chevy’s small-block, with nothing but a notch in the front crossmember needed to drop into the Sting Rays. The only clearance problems were with the 427’s magneto and Holley 4150 four-barrel carburetors, which stuck up through holes cut in the 1963 Corvettes’ hoods and were covered by what may have been one of Thompson’s blower scoops cut in half. The scoops faced forward when the cars rolled out for practice, but were turned around by the time they raced to take advantage of high-pressure air at the base of the windshield—the same principle that the Mystery Motor Impala’s cowl induction system was based on. The only modifications made to these engines were headers that fit into the Corvettes, and replacement of their 409 Delco-Remy distributors with Vertex magnetos.

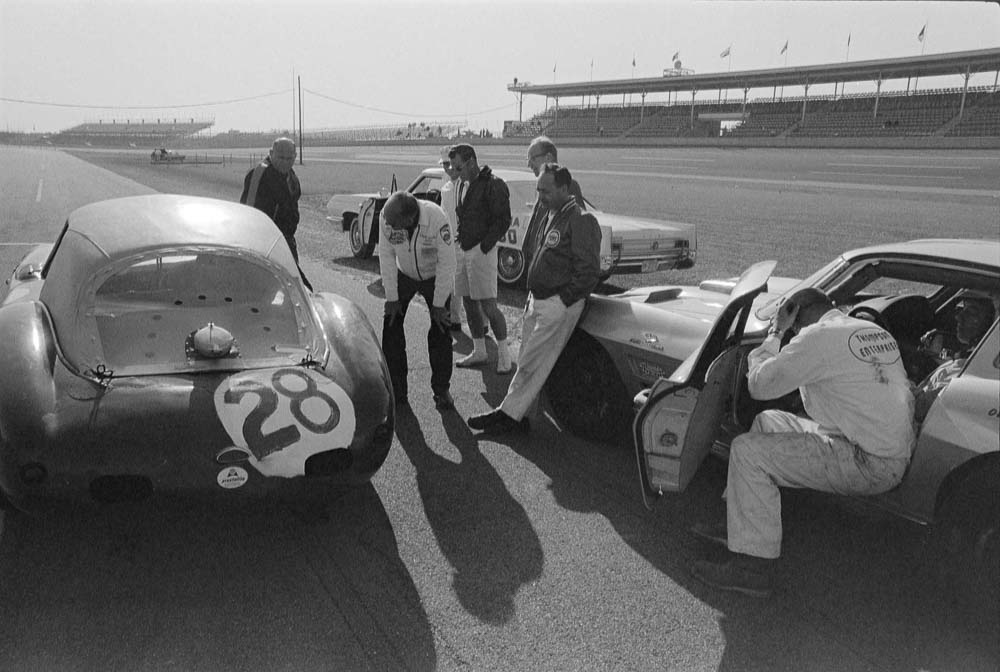

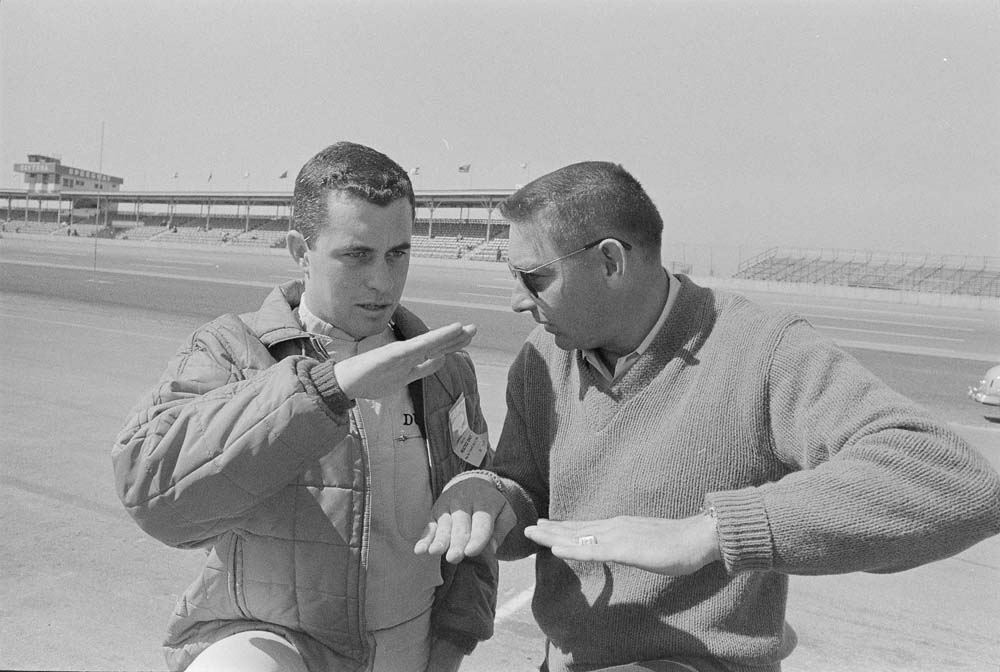

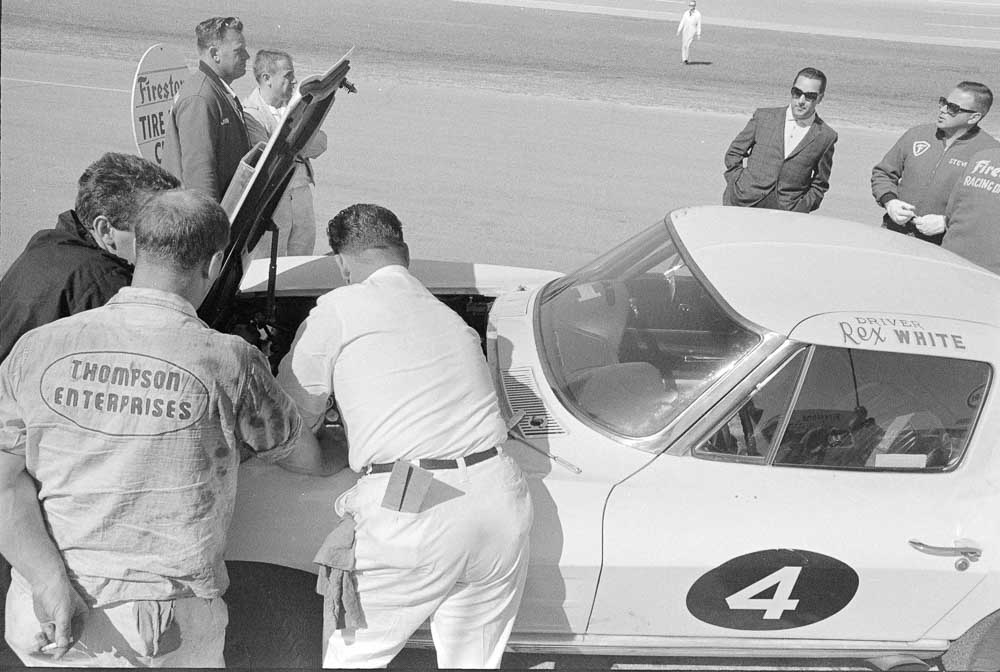

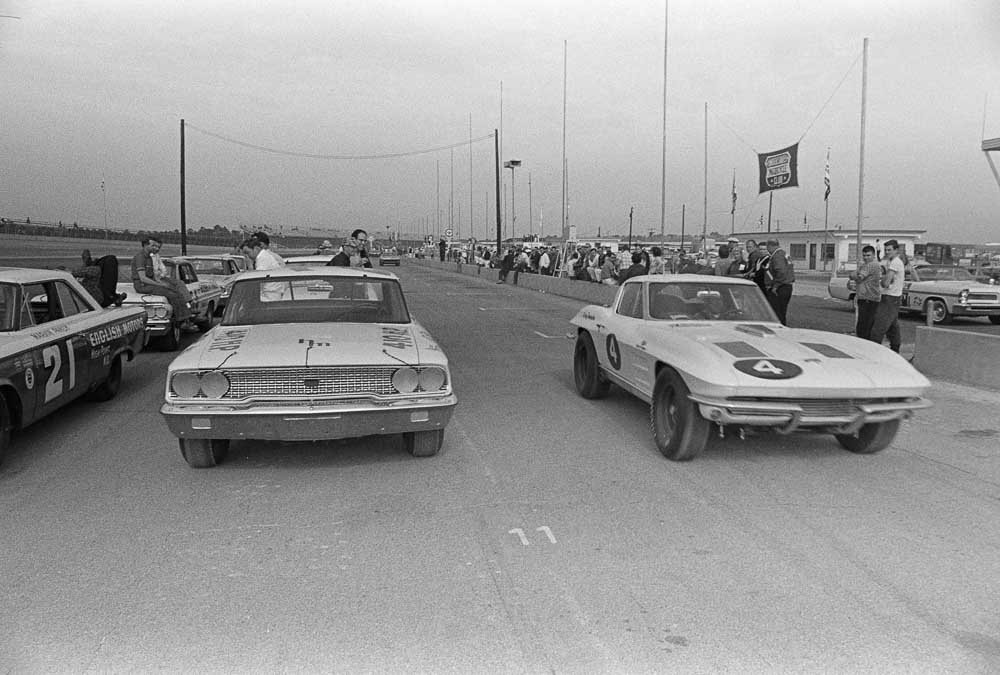

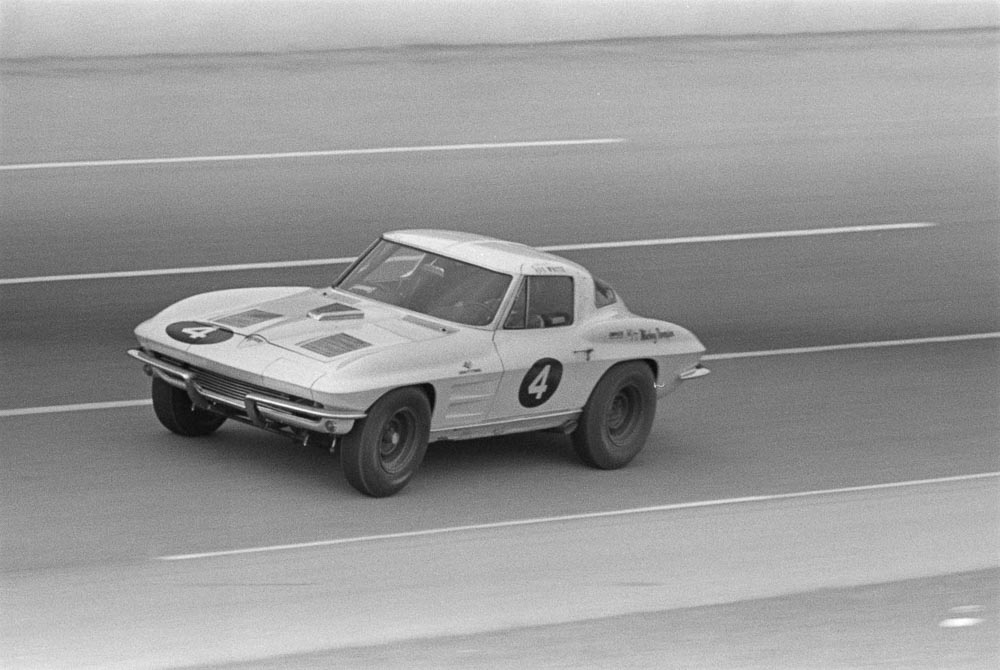

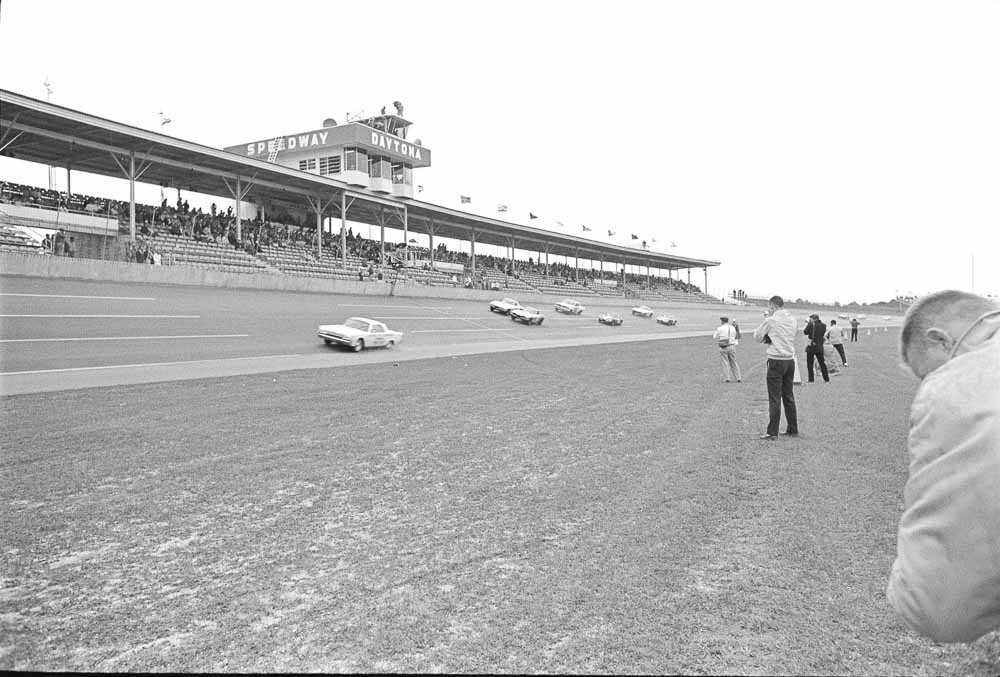

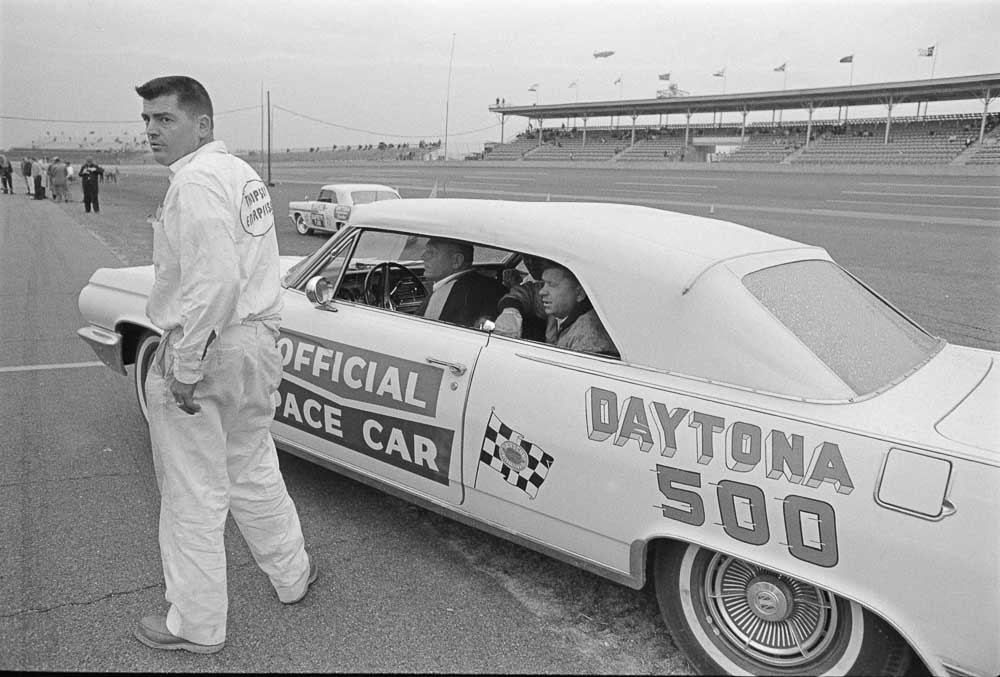

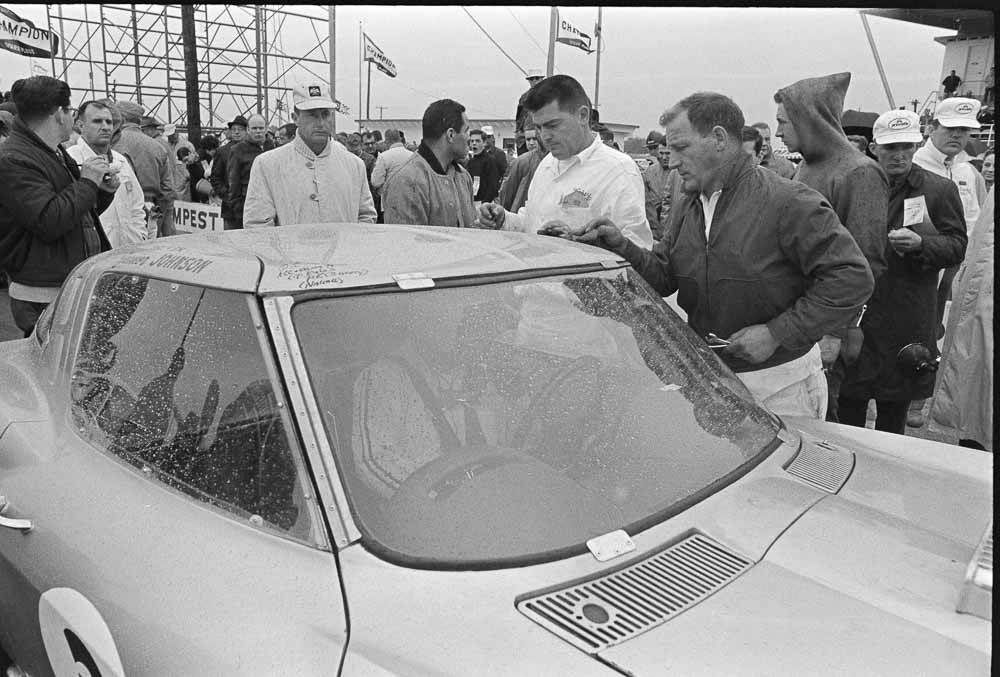

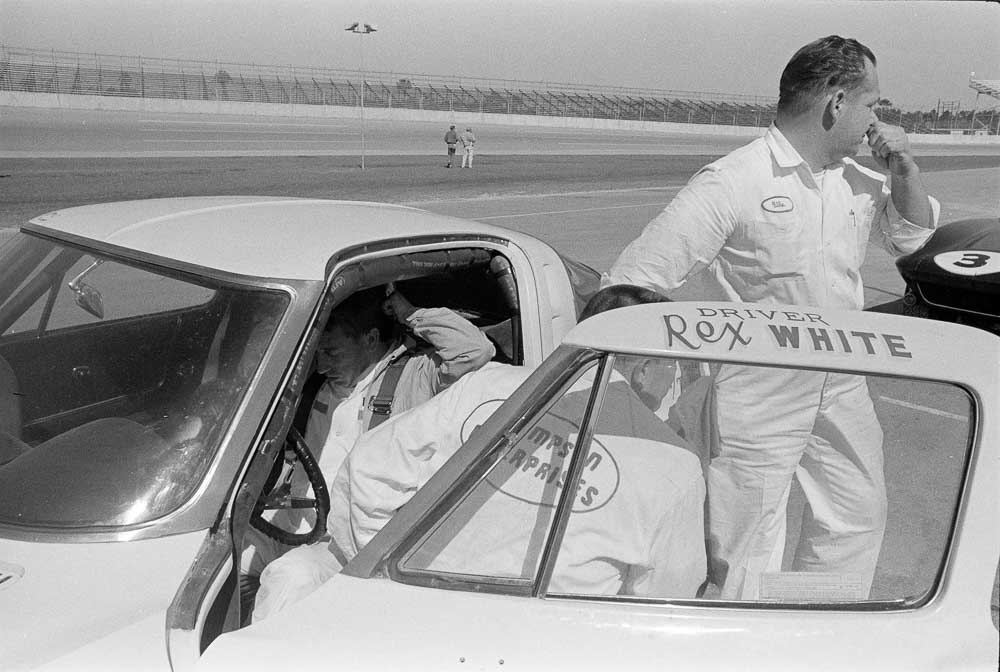

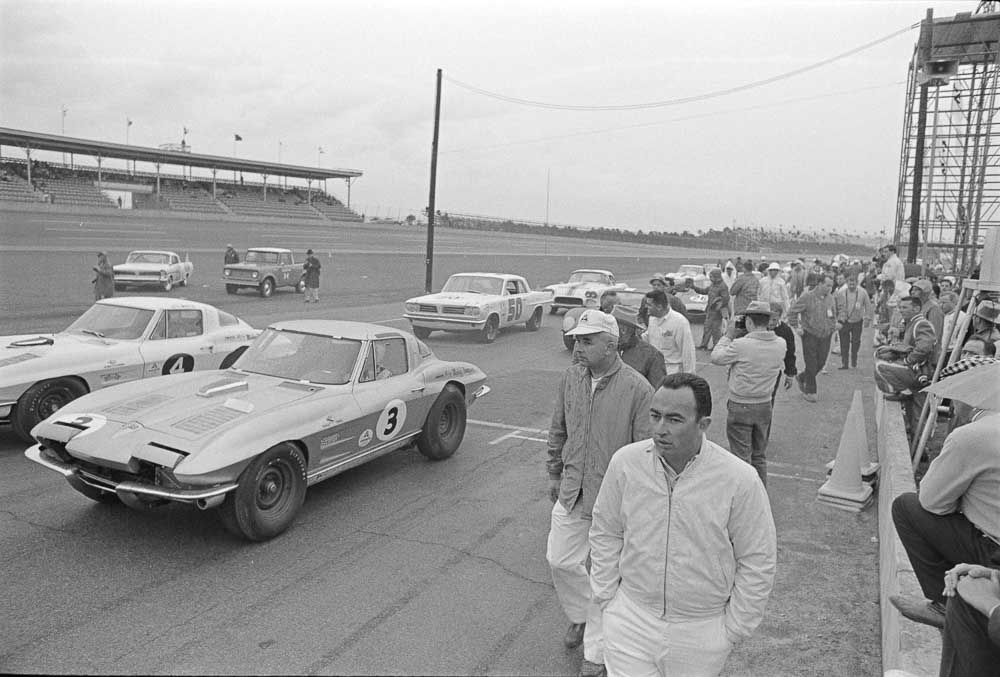

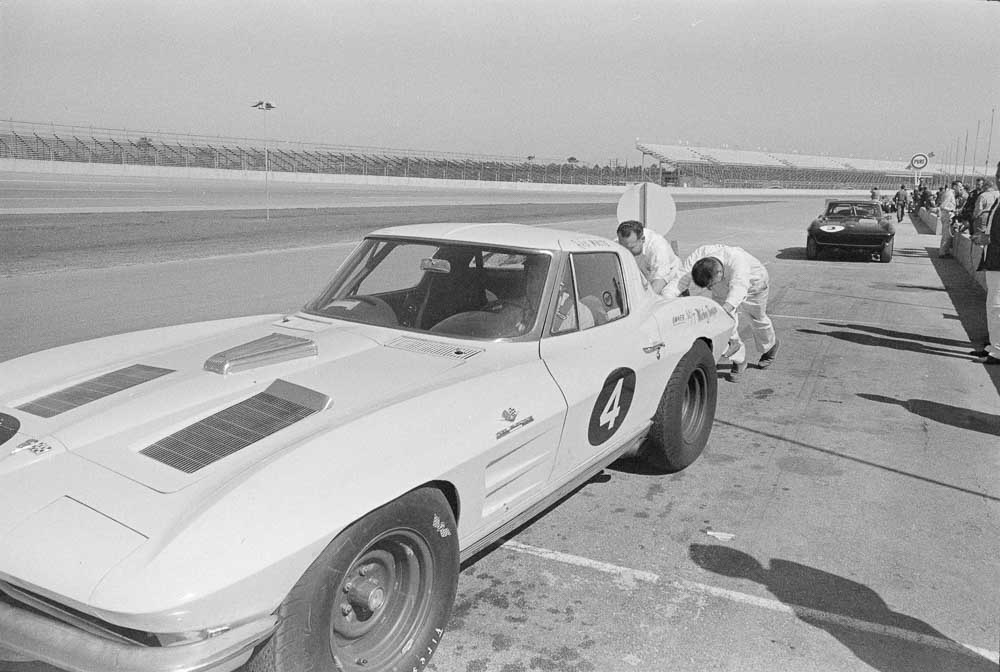

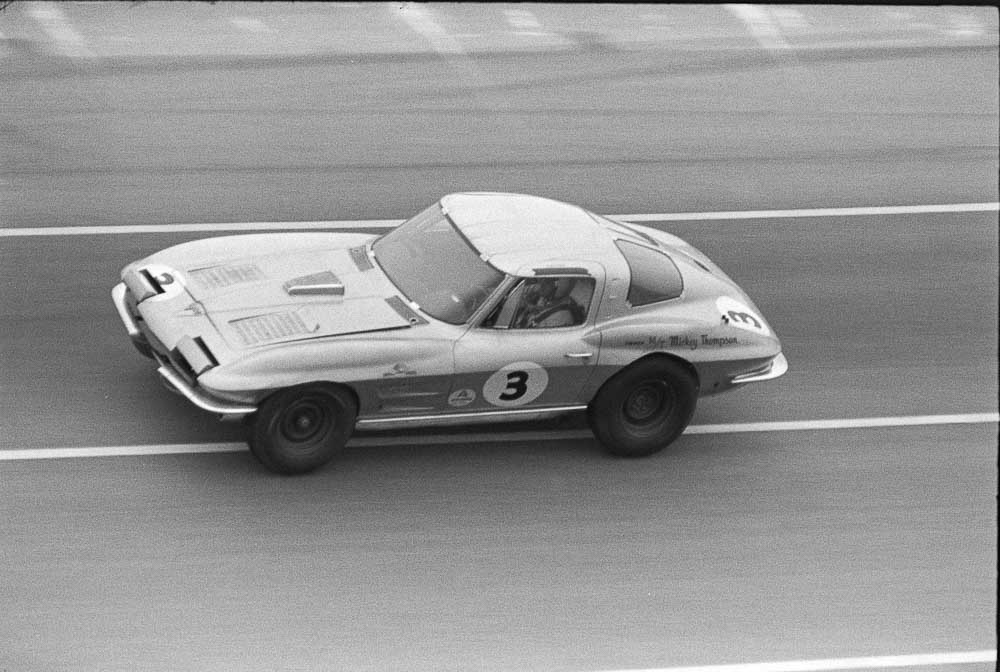

1963 Daytona Speed Month NASCAR’s Bill France was quite a showman, and by 1963 had turned Daytona Speed Week into a Speed Month with racing every weekend during February at his four-year-old Daytona International Speedway. The American Challenge Cup was presumably his idea and could have been inspired by the Race of Two Worlds, where Indy roadsters competed against Formula One and sports racing cars on the banked Monza oval track in Italy. Mickey Thompson signed two NASCAR stars who were driving Mystery Motor–powered Chevrolet Impalas in the Daytona 500 to drive his American Challenge Cup big-block Sting Rays. The 27-race-winner, Junior Johnson, was behind the wheel of the silver No. 3. Corvette, and Rex White, the 1960 Grand National Champion, who had also done the MkII engine program track testing for Chevrolet engineering, was driving the appropriately colored white No. 4 Corvette.

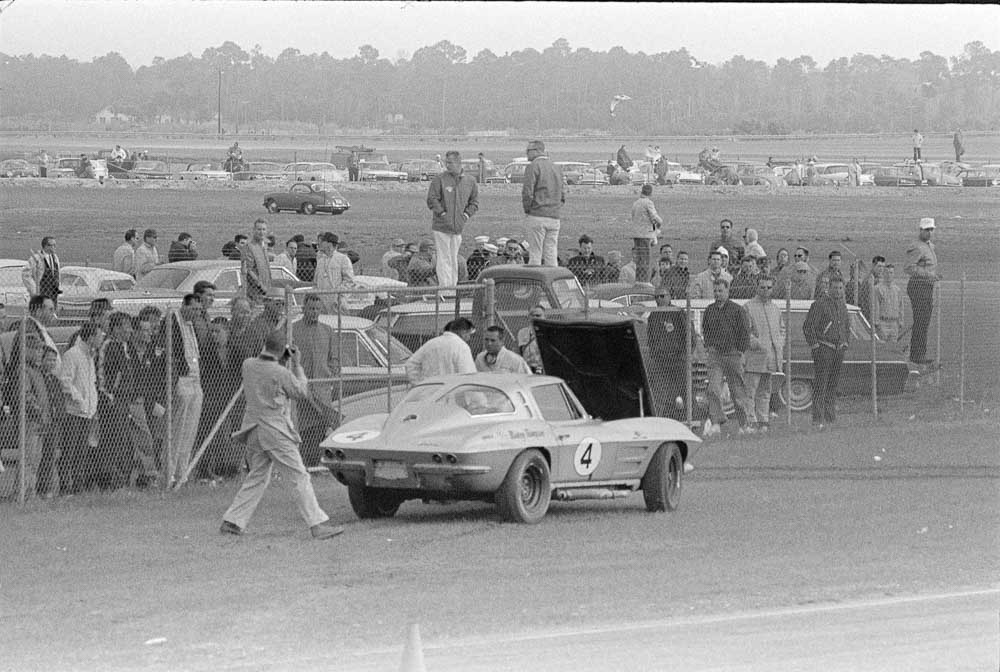

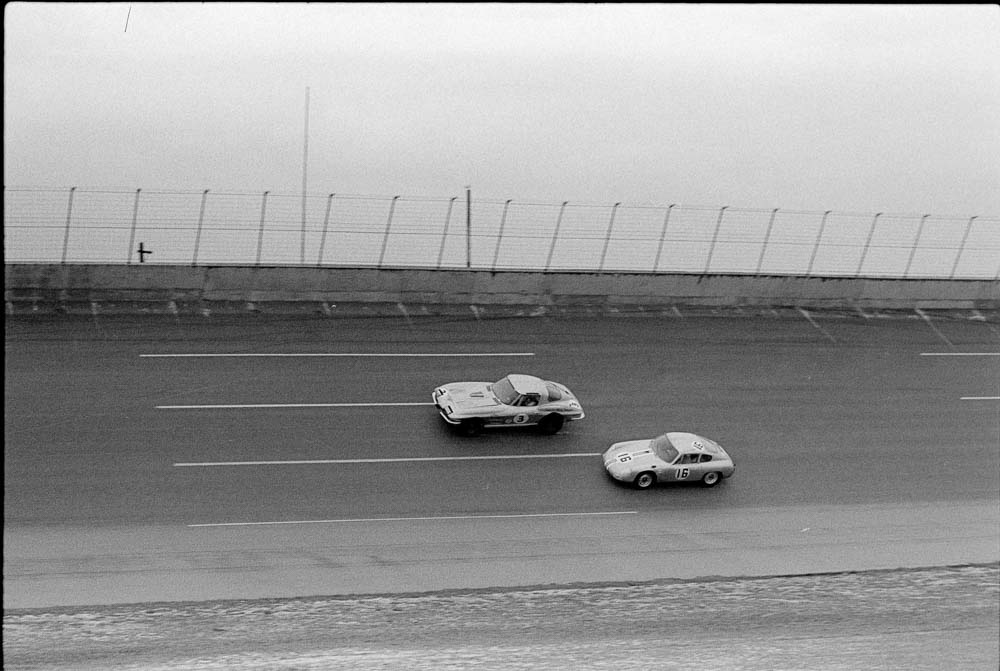

The Daytona Speed Month kicked off with a two-day Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) event on the combined tri-oval and infield road course, and most of these races were run in the rain. The following weekend on a dry track, Don Vesco became the first American to win the Grand Prix of the United States for Motorcycles. The action then moved entirely onto the tri-oval on Sunday, February 10, 1963, when there were two pre-qualifying races for the two Daytona 500 qualifying races and another race to qualify for the American Challenge Cup. Each of these was scheduled for 10 laps. Most of the American Challenge Cup and Continental cars hadn’t shown up yet, and even with Mickey Thompson entering all four of his Corvettes, the car count was only seven; with the field so small, qualifying was shortened to five laps. To no one’s surprise, Junior Johnson won this in 4 minutes, 39.40 seconds, followed by Rex White, both in Thompson’s big-block Sting Rays. Paul Goldsmith in the Ray Nichels’ 421ci Super Duty–powered Pontiac Tempest came in third.

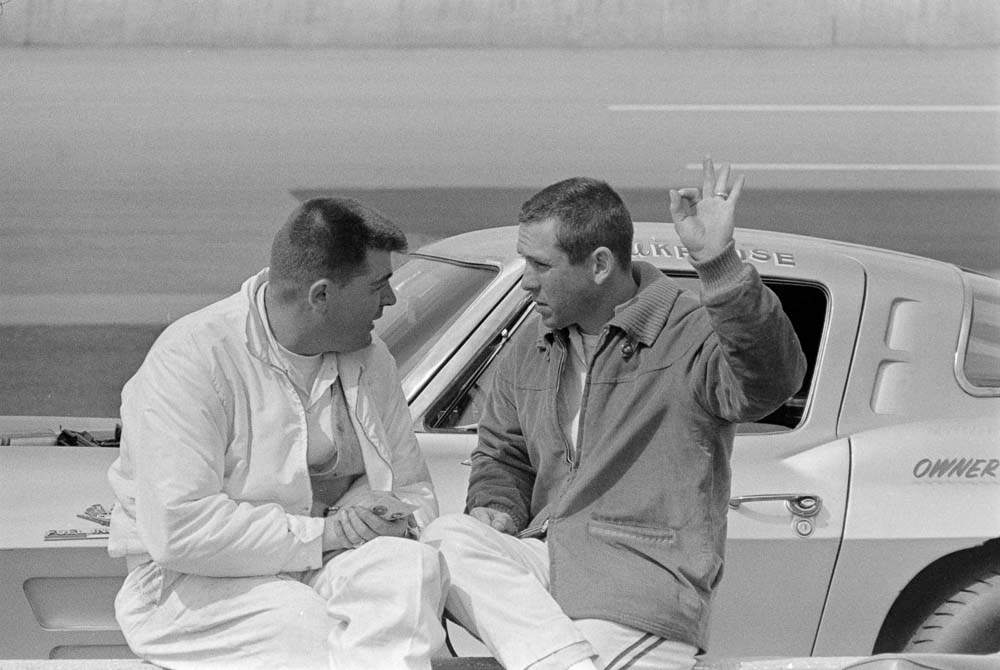

Thompson’s Corvettes were the fastest GT cars around Daytona’s tri-oval, but they were a handful to drive and Junior Johnson had an easier time lapping at 164.083 mph in Ray Fox’s 1963 Impala than he did averaging 162.220 mph driving the Corvette. Johnson felt the Z06 was capable of 180-mph laps “with the proper setup,” but Thompson and his crew were primarily drag racers, and even though he was entering his own cars for the second time in the Indy 500, they “never found the handle,” according to Johnson.

It was raining on Saturday, February 16, when the 250-mile American Challenge Cup race was scheduled to run on the tri-oval. Even though the SCCA races had run in the rain two weeks earlier, they had been on the road course and this was a NASCAR-style oval race. The Grand National cars never raced in the rain, but GT cars did, so the event started on schedule.

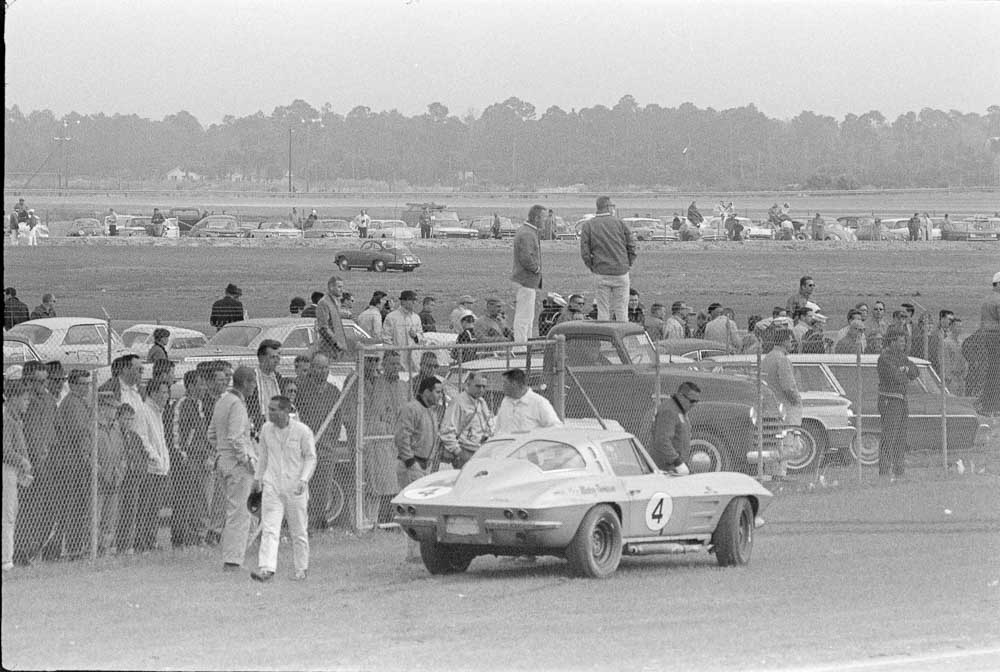

Thompson’s pair of big-block Sting Rays started from the front row where they qualified, but with Bill Krause—not Junior Johnson—behind the wheel of the silver No. 3 car. The headline in the Daytona Beach News Journal read, “Car Didn’t Act Right, Junior Got Out,” and after morning practice, the car’s handling was so evil that’s just what he did. Thompson’s crew had torn the Corvettes down in their motel parking lot the night before to look for problems, and in doing so had created new ones, not only losing what little progress they had made in the cars’ balance but making Johnson’s car worse than when it first ran.

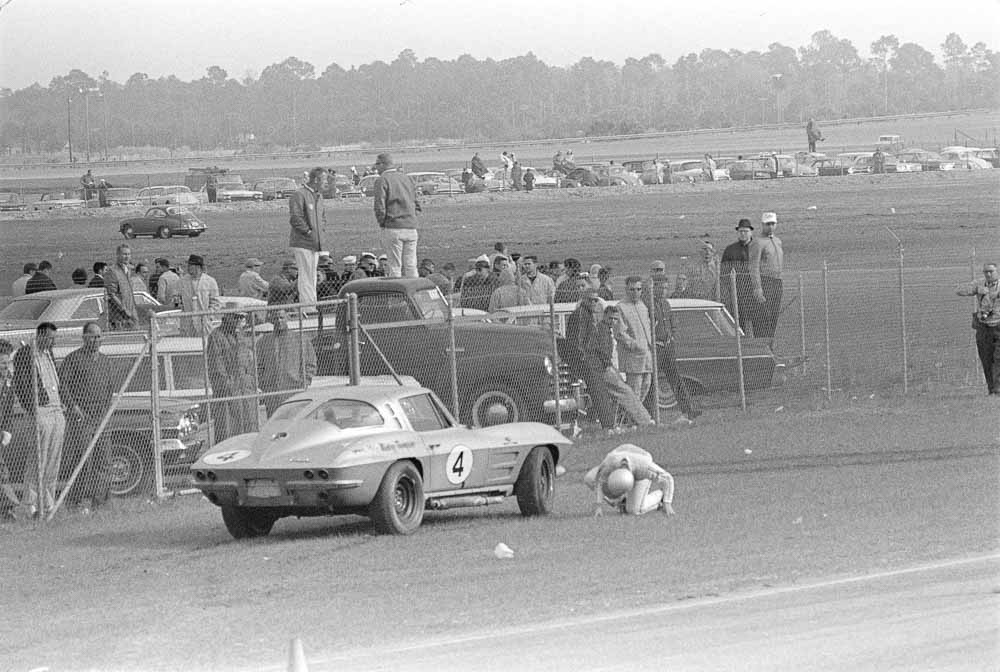

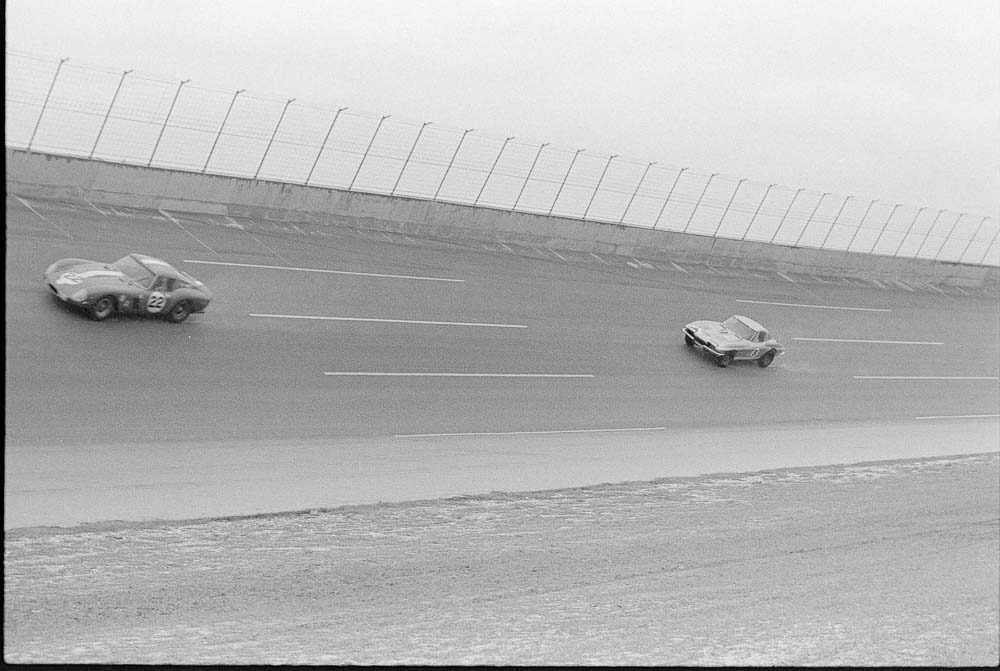

The race started with Paul Goldsmith’s Pontiac coming from the second row outside of Fire Ball Roberts’ No. 22 Ferrari GTO and blowing past the struggling Corvettes on the wet track, to take the lead on the first lap, where he would stay to the finish in the white No. 50 421ci Tempest. As the race progressed, Thompson’s Corvettes’ floorpans started taking on water that sloshed around. The exhaust systems heated the aluminum floor panels, creating steam that fogged the cars’ windshields. Handling deteriorated as the understeering monsters’ front tires wore, and after driving inside what must have felt like a microwave oven for 38 laps (at speeds of more than 150 mph), Rex White pitted the No. 4 car and told Mickey it wasn’t safe to continue because he couldn’t see. Thompson grabbed a helmet and took the car out for a lap before a rear suspension lateral link broke, bringing him back to the pits for good. Bill Krause had driven only 10 practice laps in the No. 3 car before the race started, but he toughed it out, and with his road-racing experience on wet tracks, came in a distant third to AJ Foyt in the Nickey Chevrolet’s No. 17 small-block Z06.

After Krause’s impressive drive in the Cobra at Riverside, Thompson had lured him away from Carroll Shelby with the promise of bigger things and Krause’s Third Place was the team’s best result of the weekend. For the three-hour Daytona Continental race the day after the American Challenge Cup, Pontiac somehow managed to homologate the 421 Tempest as a production GT car, and by virtue of having the largest engine in the field, Paul Goldsmith started on the pole with Bill Krause beside him. Goldsmith was out in three laps with a broken fuel pump while Krause stayed in the lead pack for half the race until his silver No. 4 Mickey Thompson Corvette’s 327 fuelie threw a rod. This was a lot better than Doug Hooper in Mickey’s Riverside-winning Daytona Blue No. 4 small-block Z06 fared, lasting only 14 laps.

Of the 12 Z06 Corvettes that started the Daytona Continental, only three finished, with Dr. Dick Thompson (no relation) coming in third behind a pair of Ferrari GTOs. This was the end of Mickey Thompson’s Corvette team’s short history, with it, as well as all of Chevrolet’s other racing activities, falling victim to a GM corporate crackdown after the Daytona 500.

Awesome photography!

Great article & photos. Thank you.

How can I get approval for this to be printed in my Corvette Club news?

Thought that was Doug sitting on the grass. Doug also won road race in the first Z06 at dodger stadium in dec 62. He passed about 2 yrs ago. But was placed in corvette hall of fame before his death ! Thanks for the article. BOB ,NCRA . NATIONAL CORVETTE RACING ASSN.

I have many photos from this event highlighting Don Yenko and the Gulf Oil Corvettes