Design of the 1952 Ford

By Jim and Cheryl Farrell

With over one-million were sold, the 1949 Ford was an unqualified success. In 1950, another million were sold, and even with war-time shortages, the sale of new ’51 Fords exceeded 900,000.

The ’49 Ford was designed mostly by outside design consultant George Walker and two of his employees, Joe Oros and Elwood Engel. Even though they had been promised long-term positions at Ford if their design won, Ford’s executive vice president Ernie Breech let Walker, Oros and Engel go because he thought it more important for Ford’s future to rebuild its own design team rather than rely on outside consultants.

Less than a year after Walker, Oros, and Engel left, Breech changed his mind and asked them to return as long-term design consultants. Although Breech still thought it important that Ford build up its own design staff, he realized Ford also needed the discipline and direction Walker and his staff could provide. However, there was a catch. Before he agreed to return, Walker insisted he be allowed to retain his own independent design consulting business, that Oros and Engel remain his employees, but have the authority to recommend changes in any clay models then being developed by Ford’s staff designers, and that they be allowed to develop their own competing designs if they didn’t like the ones Ford’s staff designers came up with.

Walker was well paid by Ford, but he was not there all the time—Oros and Engel were. Upon their return, Oros set up shop in the Ford studio, while Engel did the same in the Lincoln-Mercury studio. Needless to say, Oros and Engel were tolerated, but they weren’t warmly welcomed back by Ford designers.

Walker had earlier recruited two clay modelers from GM, Charlie and Leonard Stobar, to make clay models of his firm’s design proposals so clients could see what they were getting. When Walker returned to Ford, he arranged for the Stobar brothers to be hired as Ford clay modelers.

Although Ford designers proposed many changes for the 1950 and 1951 Fords, Henry Ford II liked the looks of the ’49 Ford and saw no need for a new model until 1952. The end result was that HFII vetoed major design changes in ’50 and ‘51. He did agree to a series of improvements to the ’49 Ford to rectify some of the problems missed during the car’s accelerated development schedule. Tom Dingman, a body engineer from Studebaker, was hired to revise door hardware. By the time Dingman was done, Ford was able to boast that the ’50 Ford had been improved in 50 different ways.

The rebuilding process at Ford involved hiring experienced managers, accountants, engineers, designers and planners mostly from other car companies by offering double the salary those employees were earning elsewhere, plus the promise of quick promotions. Ford was also building new factories, a new research and engineering lab, and a new design center, all at a cost of over $20 million.

Post World War II, design was still part of Ford’s Engineering Department. In late 1949, after hiring and firing several design administrators, Charles Waterhouse was hired to oversee Ford’s design efforts. Waterhouse was not really a designer, although he had design experience. Waterhouse was a good administrator, and was well liked and respected by Ford’s designers and engineers, and he continued the studio system initiated at Ford by George Snyder.

Gil Spear, who had productionized the ’49 Ford and was head of the Ford design studio during the time the 1950 and ’51 Fords were developed, was asked to begin a Ford advanced design studio to tackle long range projects and teach new designers the “Ford way” of designing cars. When Spear started Ford’s new advanced studio, Frank Bianchi was appointed to replace him as head of the Ford studio. Bianchi soon ran into problems and was let go after only a few months. Bob Maguire, a former GM designer, was then appointed to head the Ford design studio.

For 1952, Ford planned to introduce an all-new body style with multiple engineering and design improvements. Maguire’s primary job was to come up with an acceptable design direction for the ’52 Ford. There was a problem, however. Many of Ford’s newly hired designers also came from GM, and their designs often looked like they also came from GM.

Soon after they return to Ford, Oros convinced Walker and Ford management that Ford needed to build its own showcar to match two currently being developed at GM. Oros felt that one of the coming trends in car design was the jet fighter look, and he wanted to capitalize on it in his own special way before the theme was taken by GM or another automobile manufacturer. Oros urged that Ford develop a distinctive theme for its own showcar that could also be used on future use on Ford’s production cars. Oros’ new showcar car was soon named the X-100. (See a previous post on Dean’s Garage featuring the X-100.)

The farther along Oros got with his X-100 showcar, the more enthusiasm it generated. Soon, HFII dropped by to see it. He was so impressed, he decided it was going to be the next Continental, so the name was changed to the Continental 195X. (The name was eventually returned to the X-100 when Bill Ford’s new Special Products Division decided to develop an entirely new design as the reborn Continental Mark II.)

Oros believed that whatever the production ’52 Ford looked like, it had to be distinct and not look similar to anything being developed by the competition. Oros also quickly concluded that the ’52 Ford proposals then being developed in the Ford studio had “problems that couldn’t be corrected,” which was a nice way of saying that Maguire’s ’52 Ford proposal didn’t look unique or distinctive.

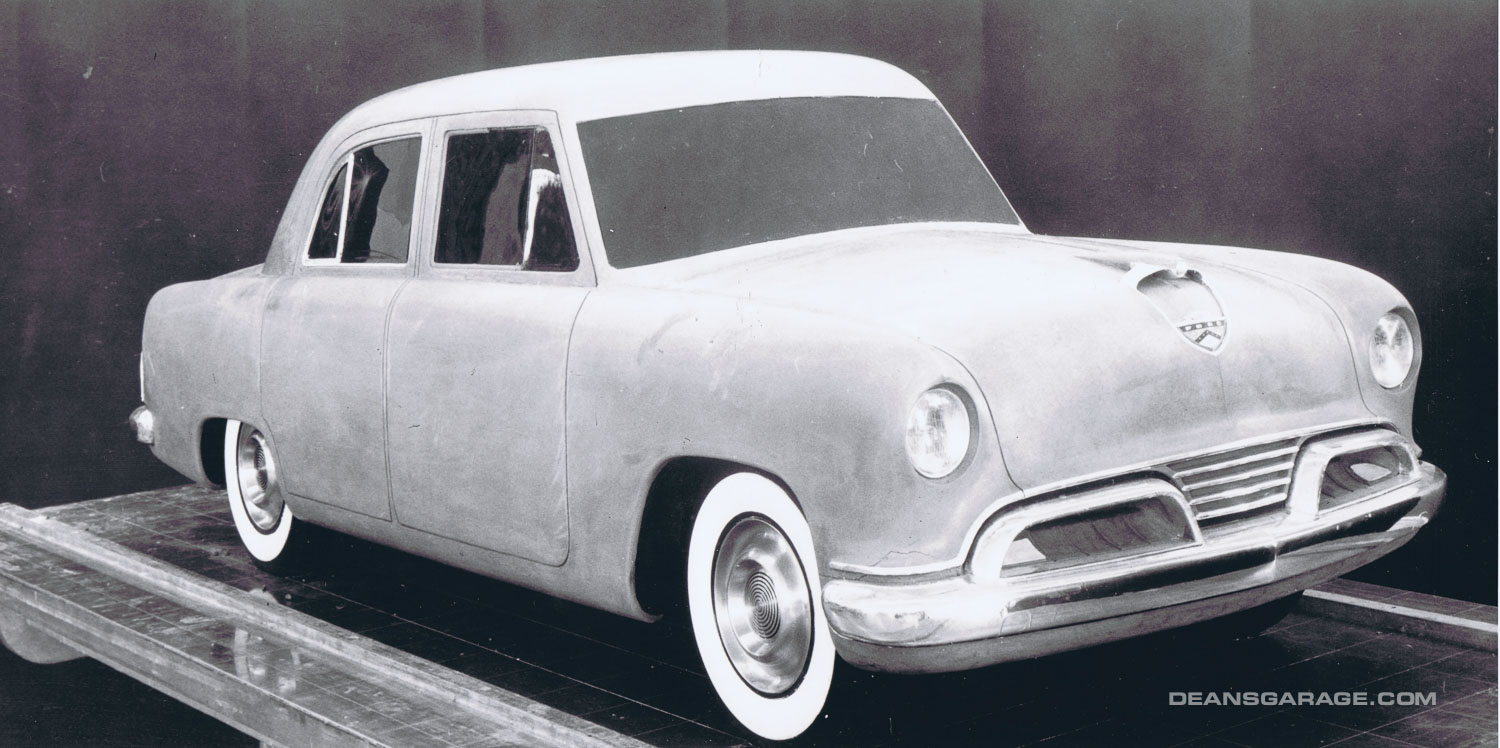

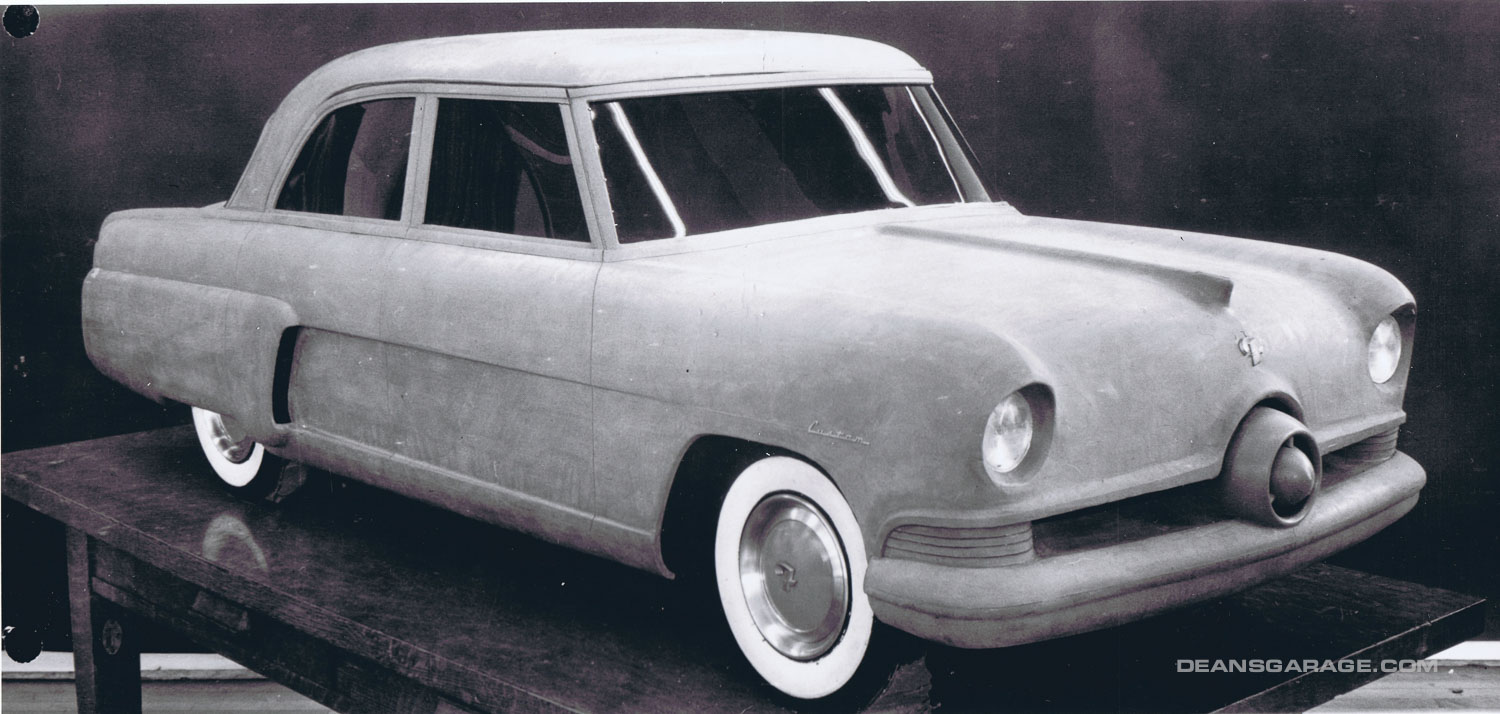

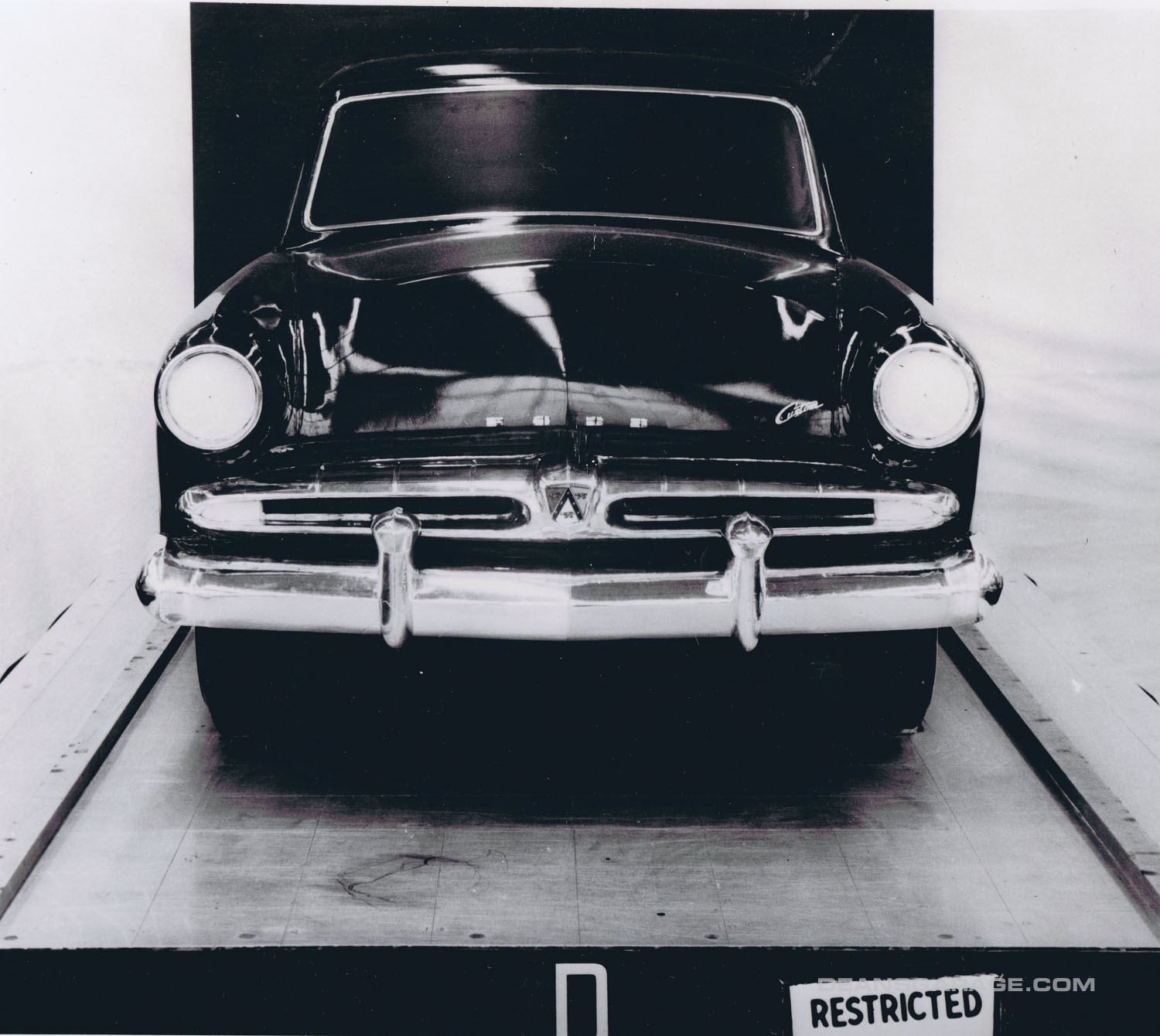

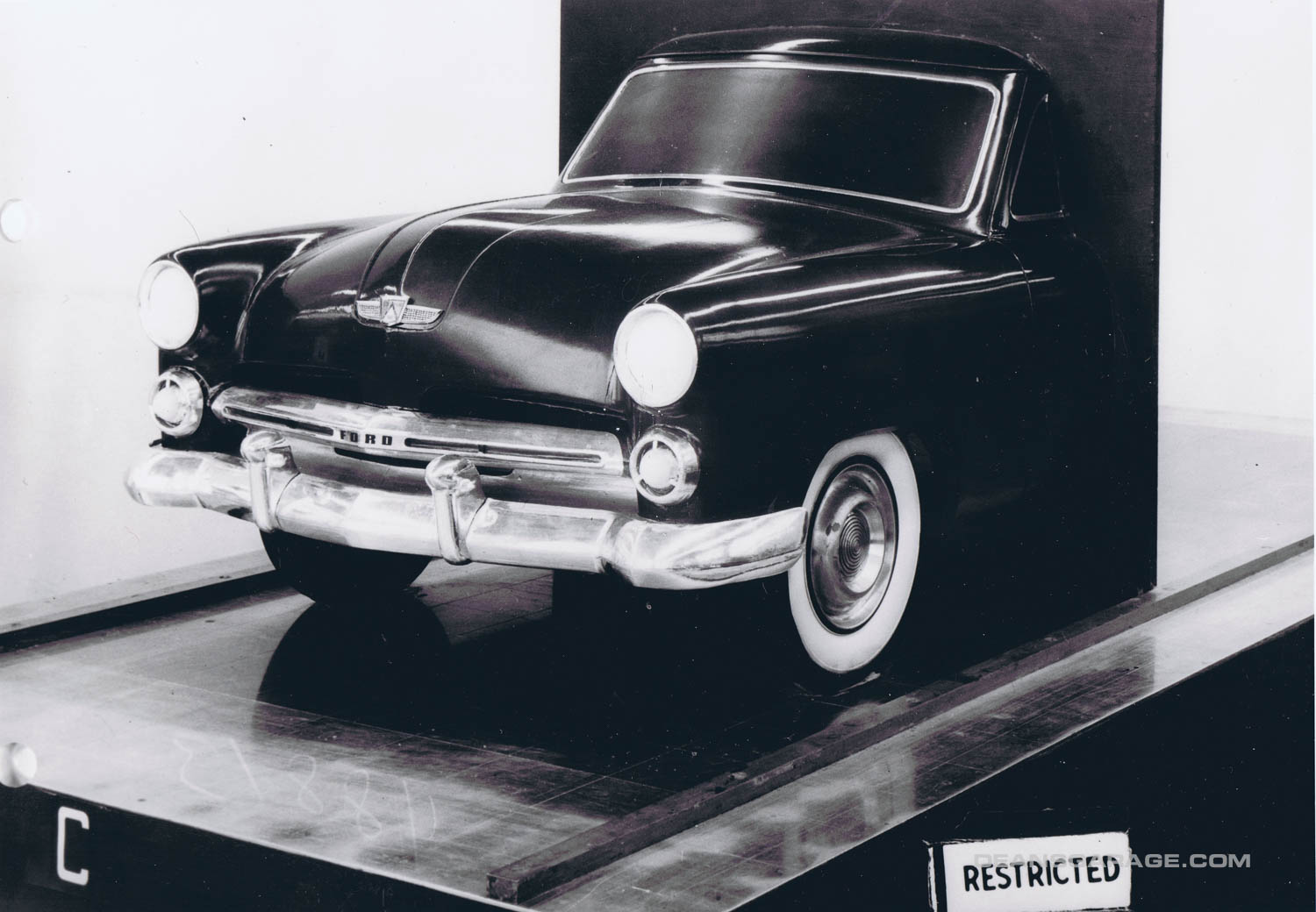

After the theme for the X-100 was set, Oros began his own clay model of what he thought the ’52 Ford should look like. Oros also asked the Stobar brothers to help clay model his ’52 Ford proposal. Oros’ proposal started as a 3/8-sized model and followed the same general theme of the X-100, only it was much more conservative, given the production restrictions of the day and perceived public tastes. As Oros puts it, his ’52 Ford production car proposal “lunched off” his showcar. Oros also pointed out his ‘52 Ford proposal was intended to show continuity with the ’49 Ford, especially the spinner grille he had designed.

When completed, the Maguire and Oros proposals were shown to Ford’s management. Management selected the body from Oros’ proposal, but ordered more work on the front and back ends of the car. Oros said that Maguire’s ‘52 Ford studio proposal fizzled out because its designers could never get past their model’s “inherent problems.”

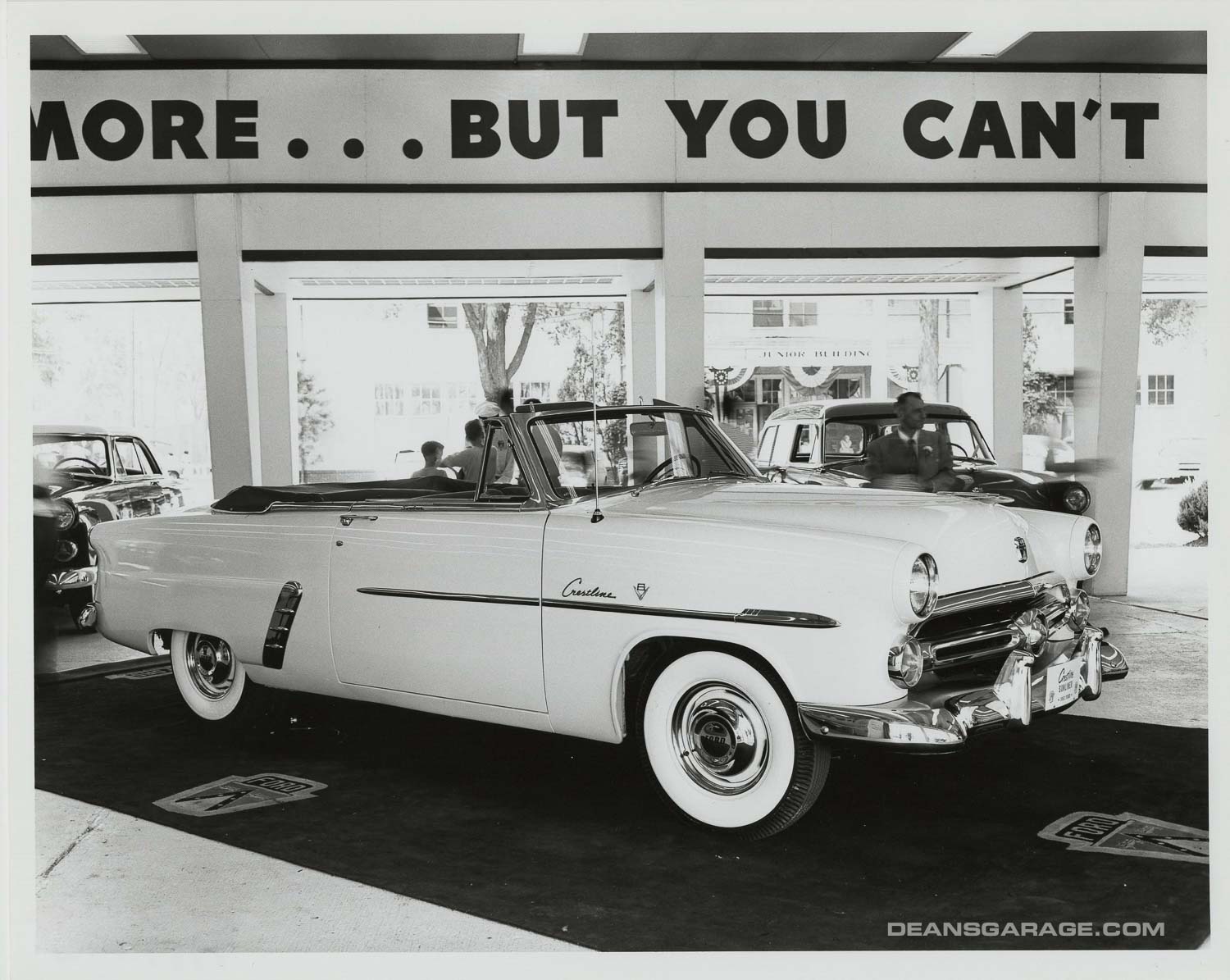

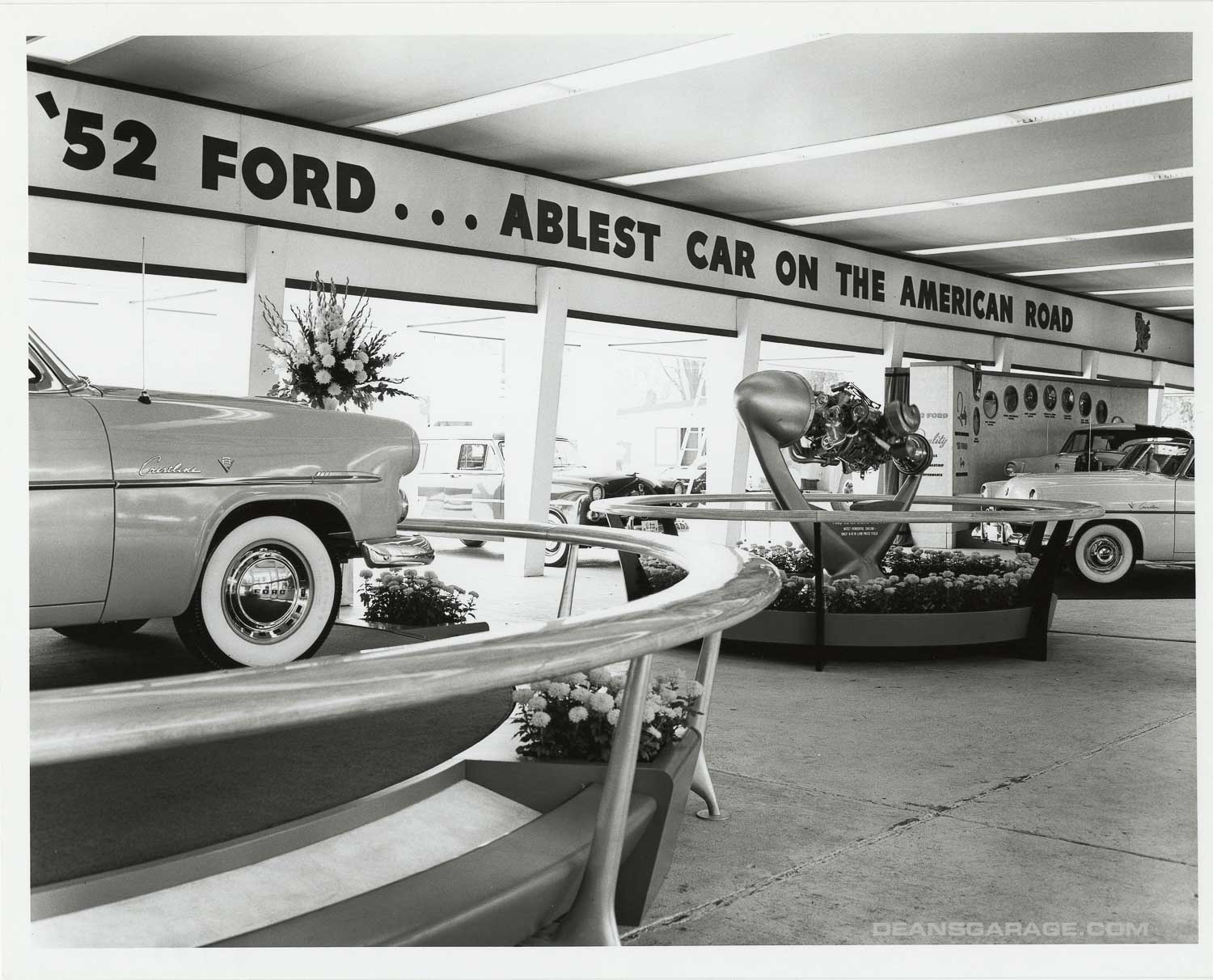

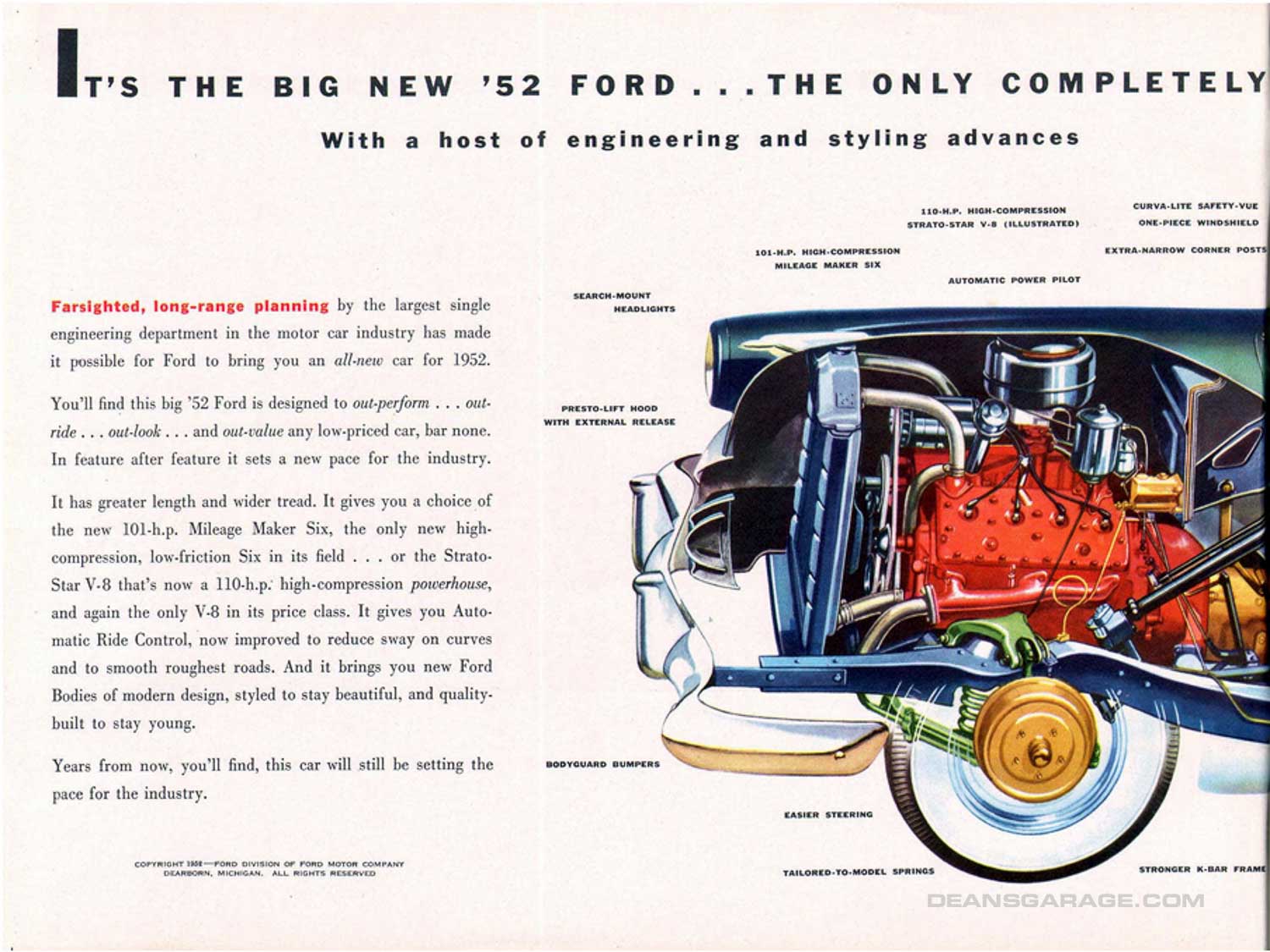

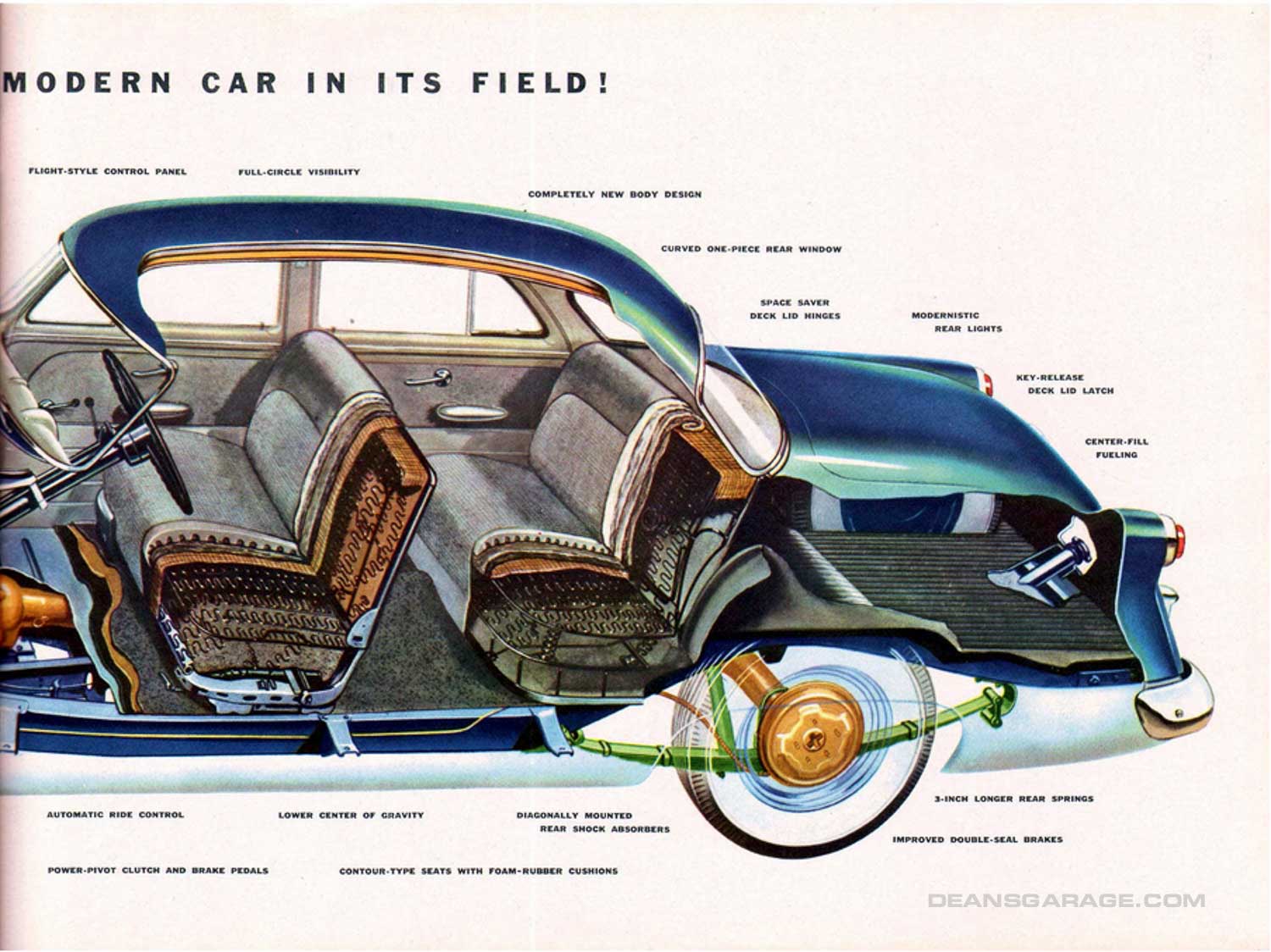

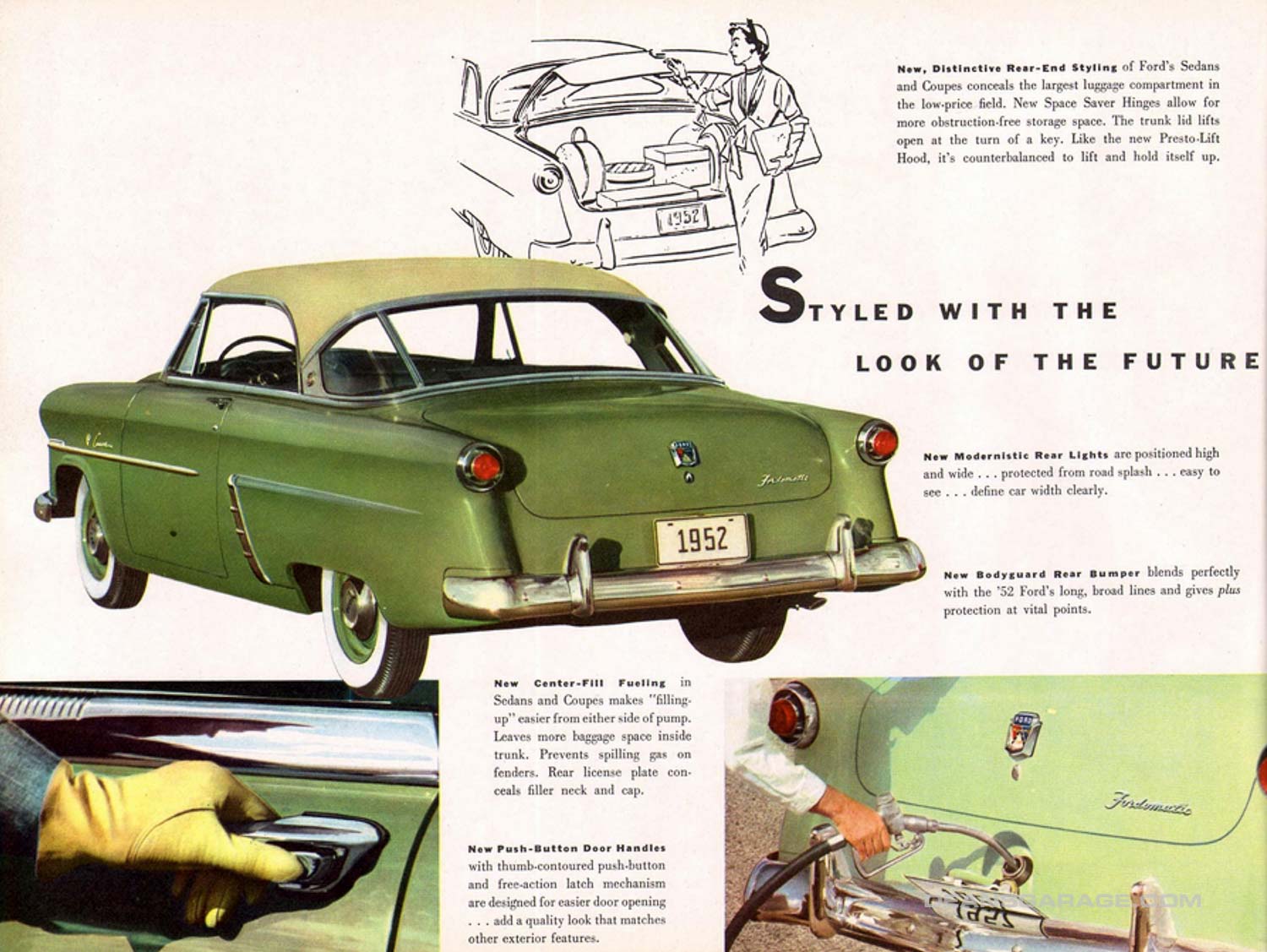

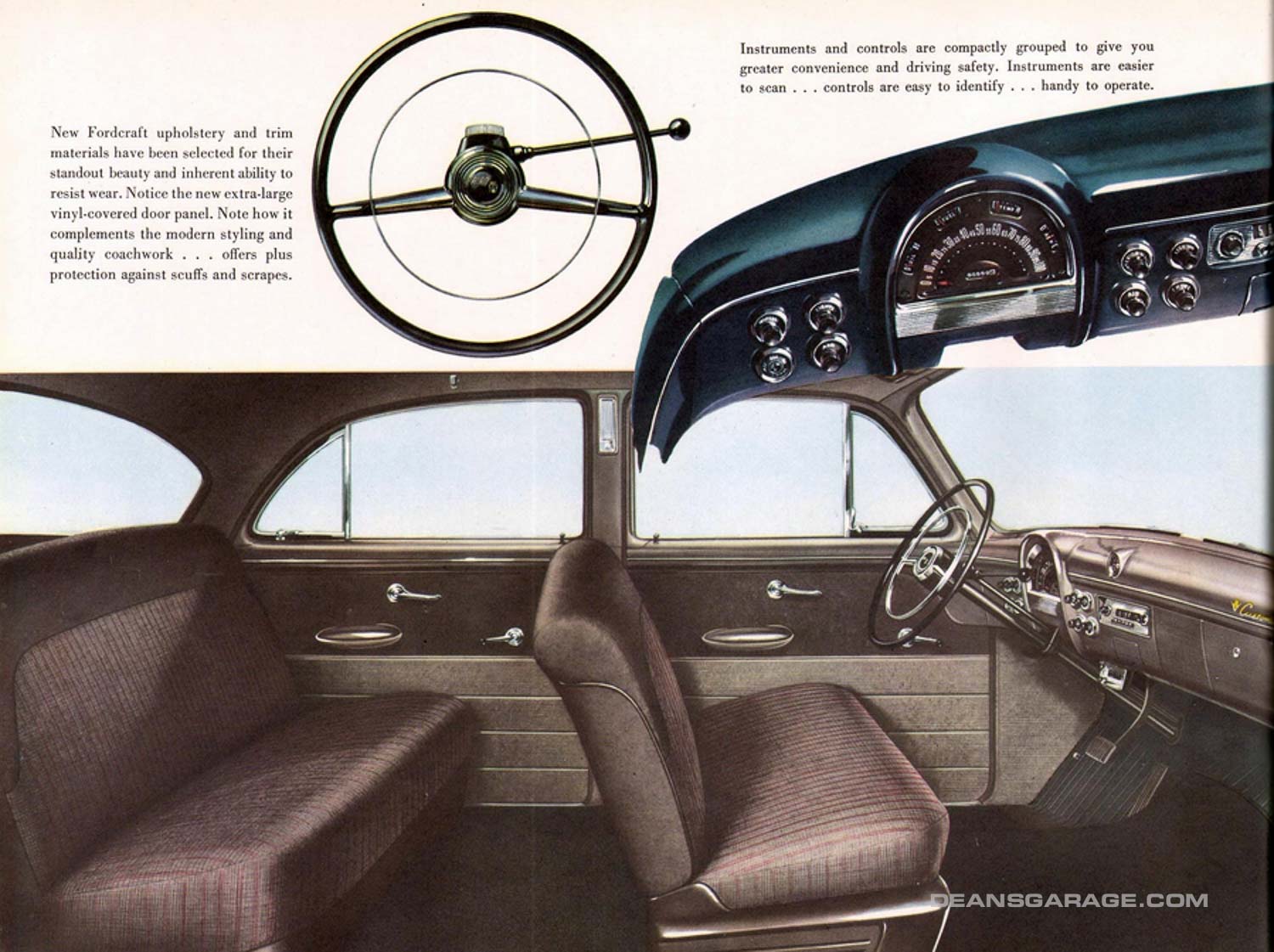

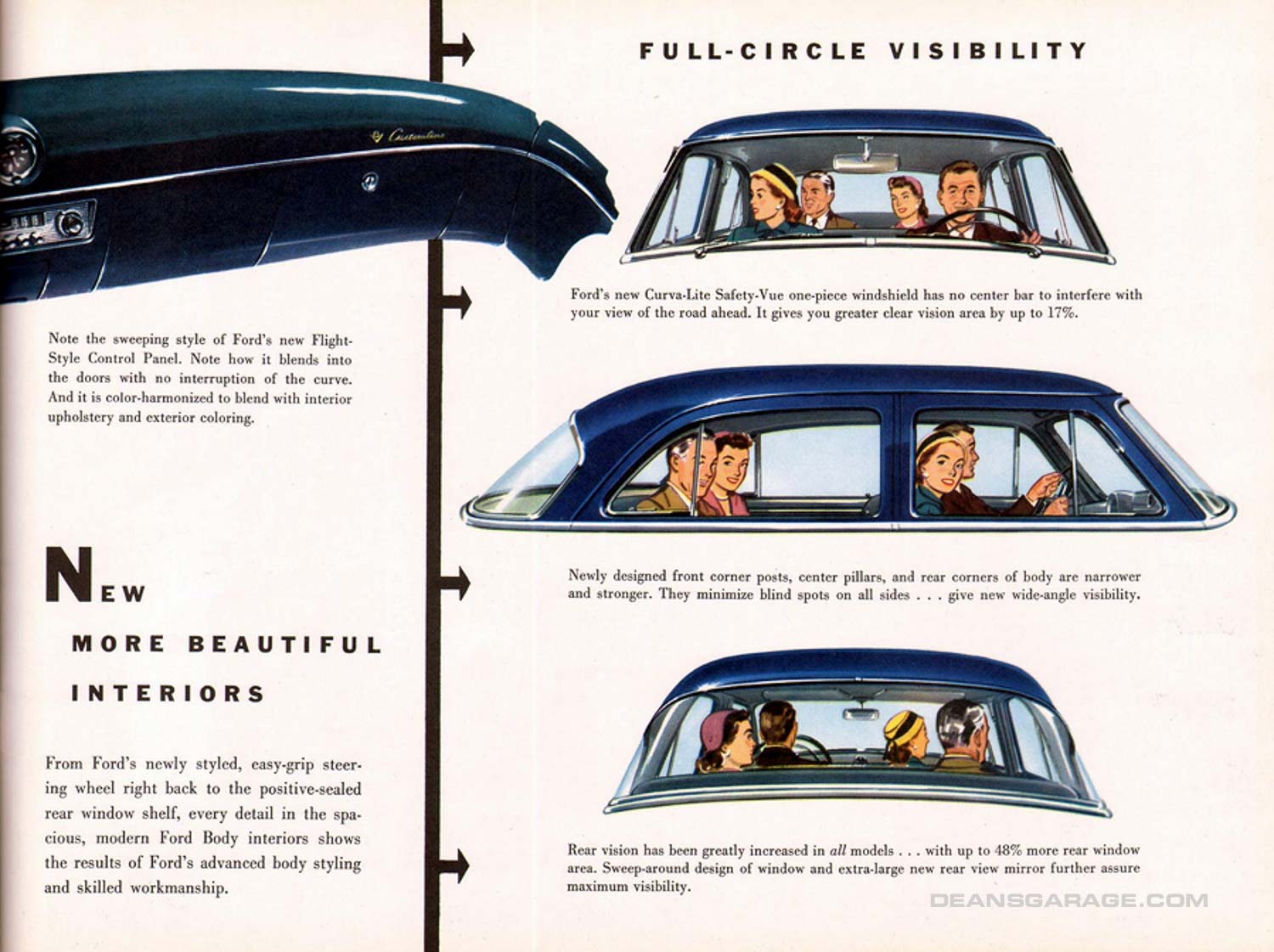

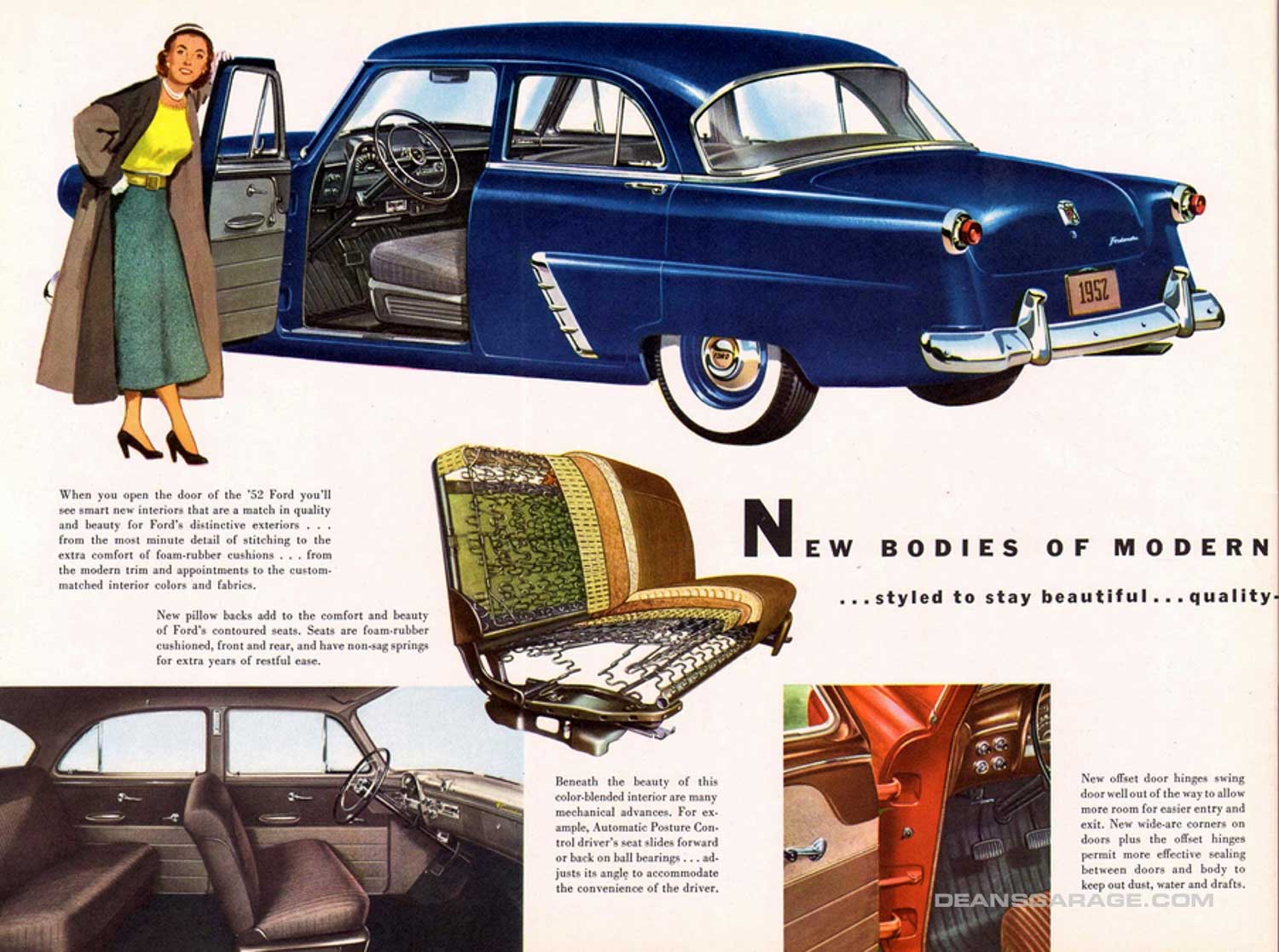

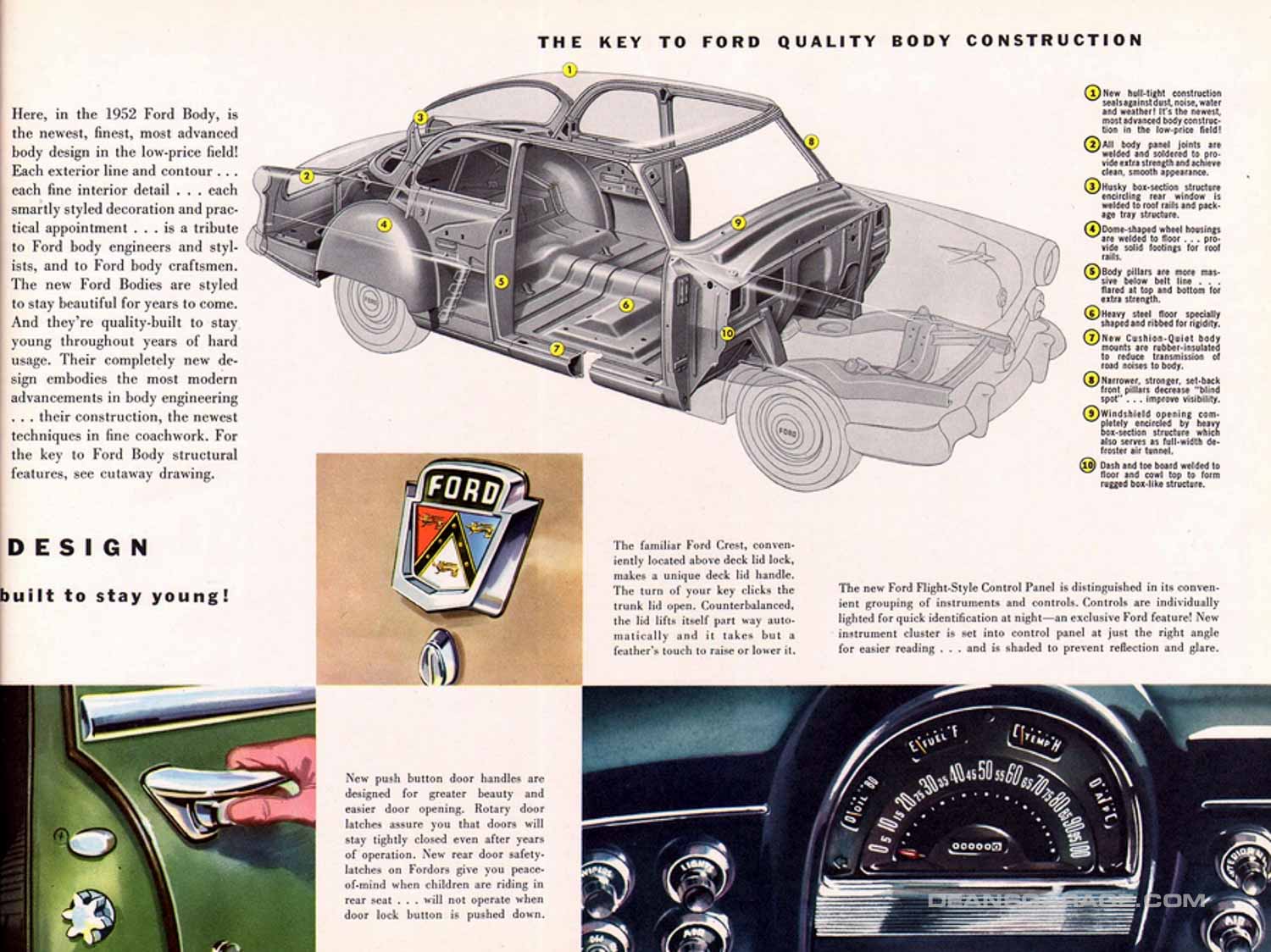

Oros’ ’52 Ford body design incorporated high fenders with a slightly lower hood and rear deck. The top of the fender line and belt molding formed unbroken lines over the distance of the entire car, which was supposed to make it look longer. The windshield and backlight were bigger than the previous year, and were one-piece curved glass. (Some backlights on ‘52 Fords were initially three pieces.) The A-pillars were also noticeably smaller than on the previous model.

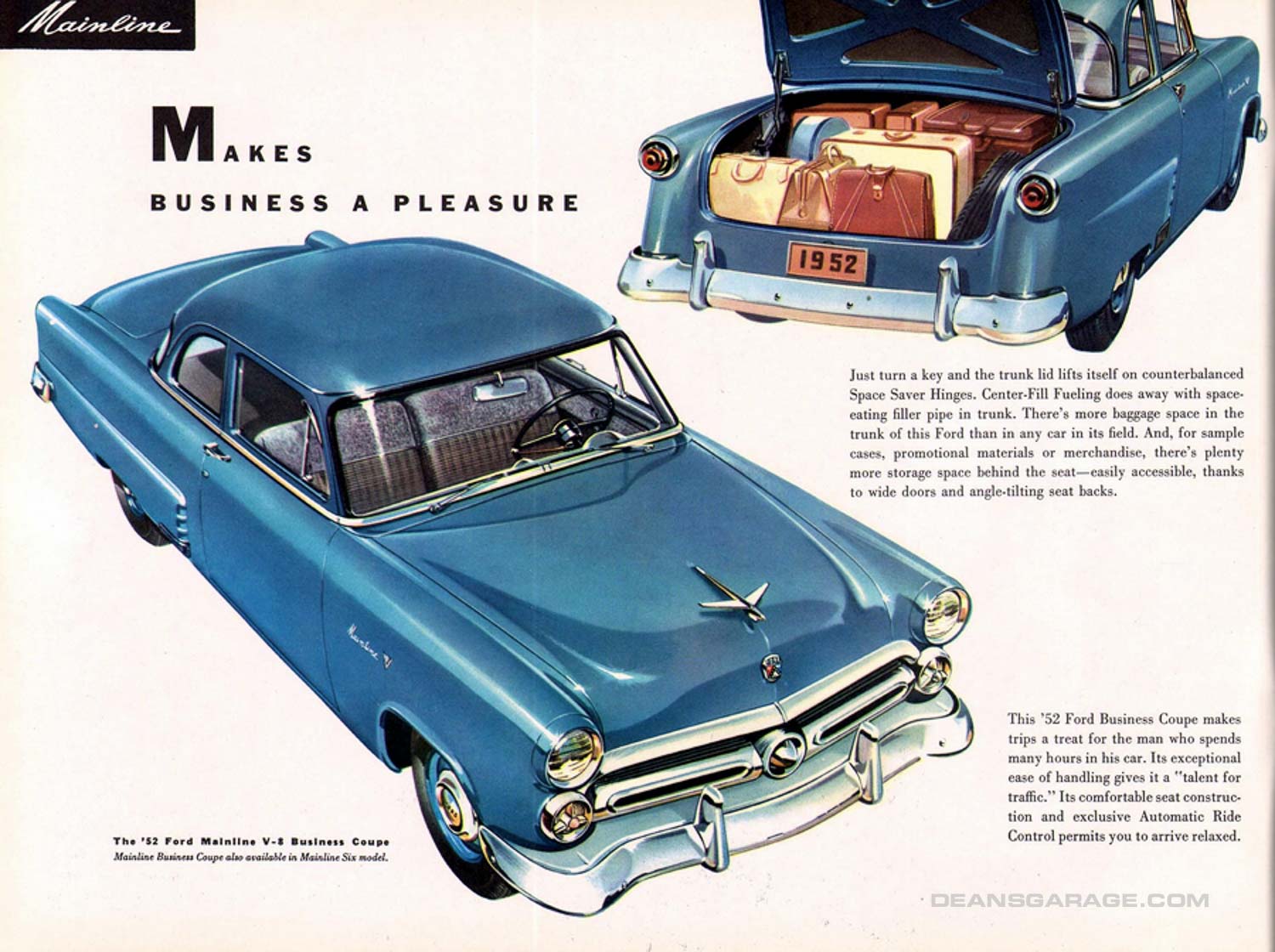

Eventually the themes Oros developed for the front and rear ends of the ‘52 Ford were also accepted by Ford’s management. The frenched headlamps and the rounded taillamps Oros developed were meant to carry through from front to rear of the car. Oros’ distinctive round taillamps were originally 5/8” to 3/4” bigger than in production. The grille came after several tries, and it was what Oros called a “three-spinner design” with parking lights inside spinners set at the outer ends of the grille bar in the fenders.

The ‘52 Ford was the first car to adopt its theme from the jet plane-inspired X-100, and Oros hoped that some of those same design cues from the X-100 would be incorporated on future Fords. The rounded taillamps, first used on the ‘52 Ford, were incorporated on future Fords for many years.

Another designer also made a significant contribution to the ‘52 Ford. At the same time Maguire and Oros were working on their ‘52 Ford proposals, Gordon Buehrig of Cord-Auburn-Duesenberg fame was hired as manager of Ford’s Body Development studio, where all Ford and Lincoln-Mercury special body styles, including convertible and station wagon models, were developed.

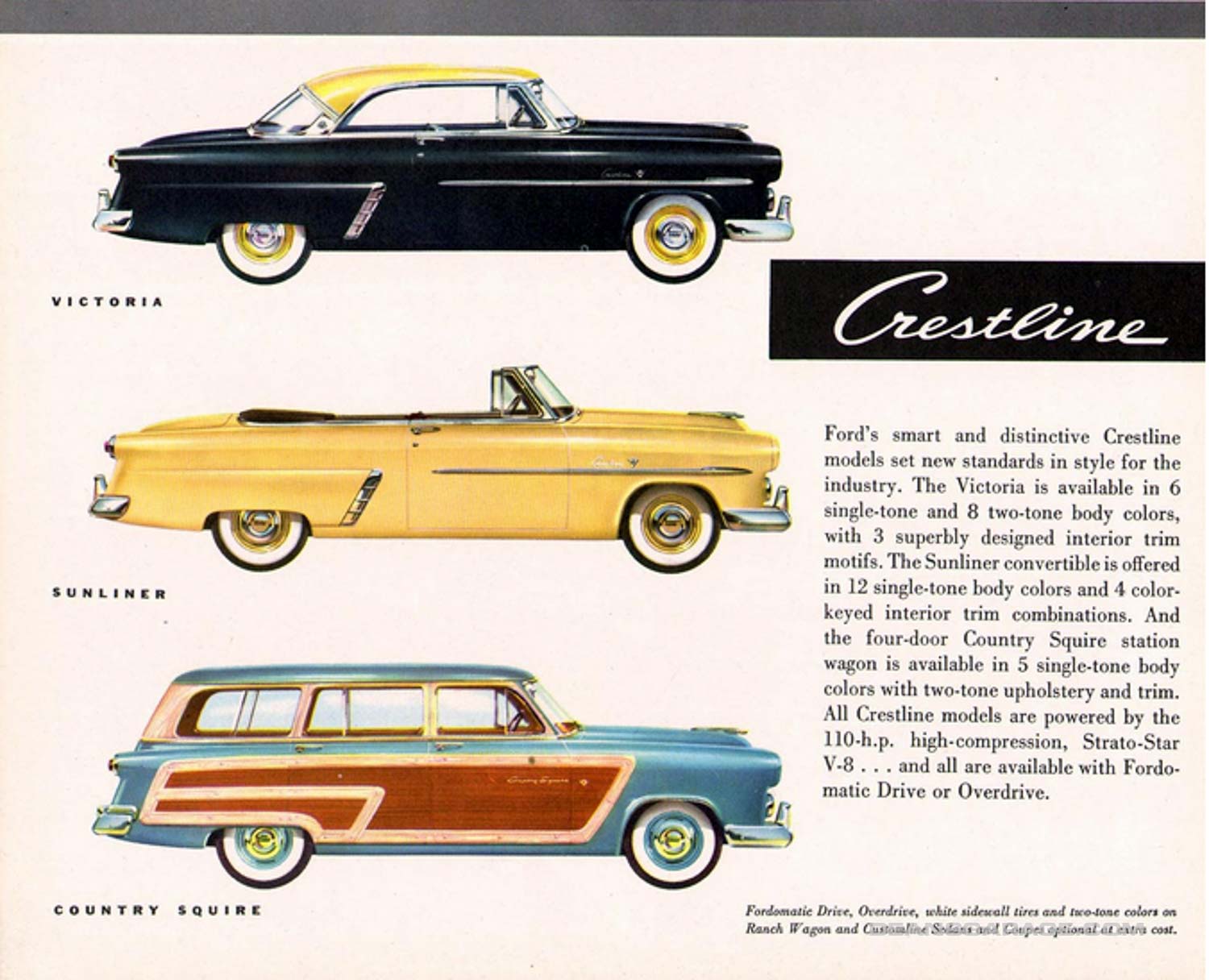

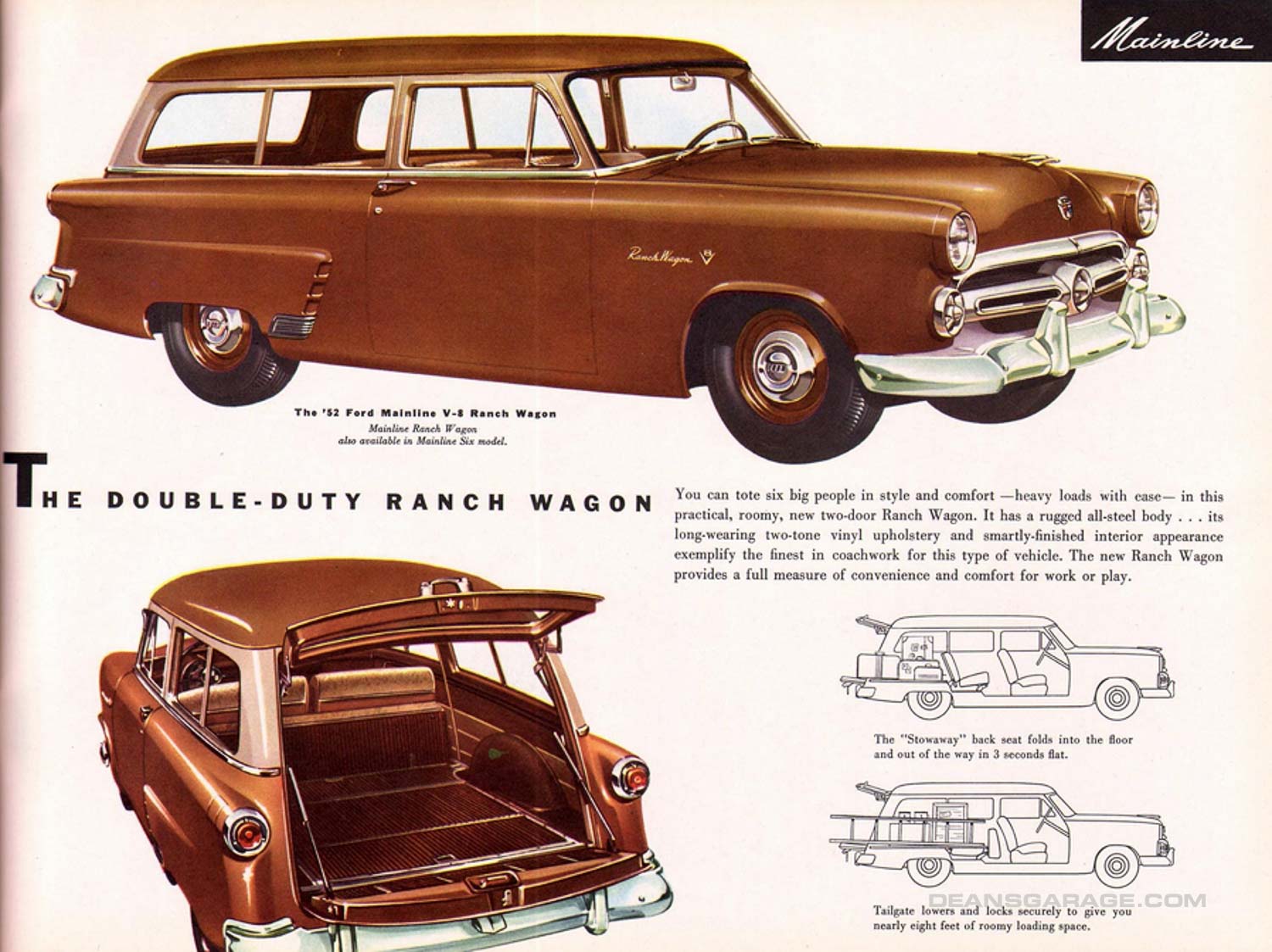

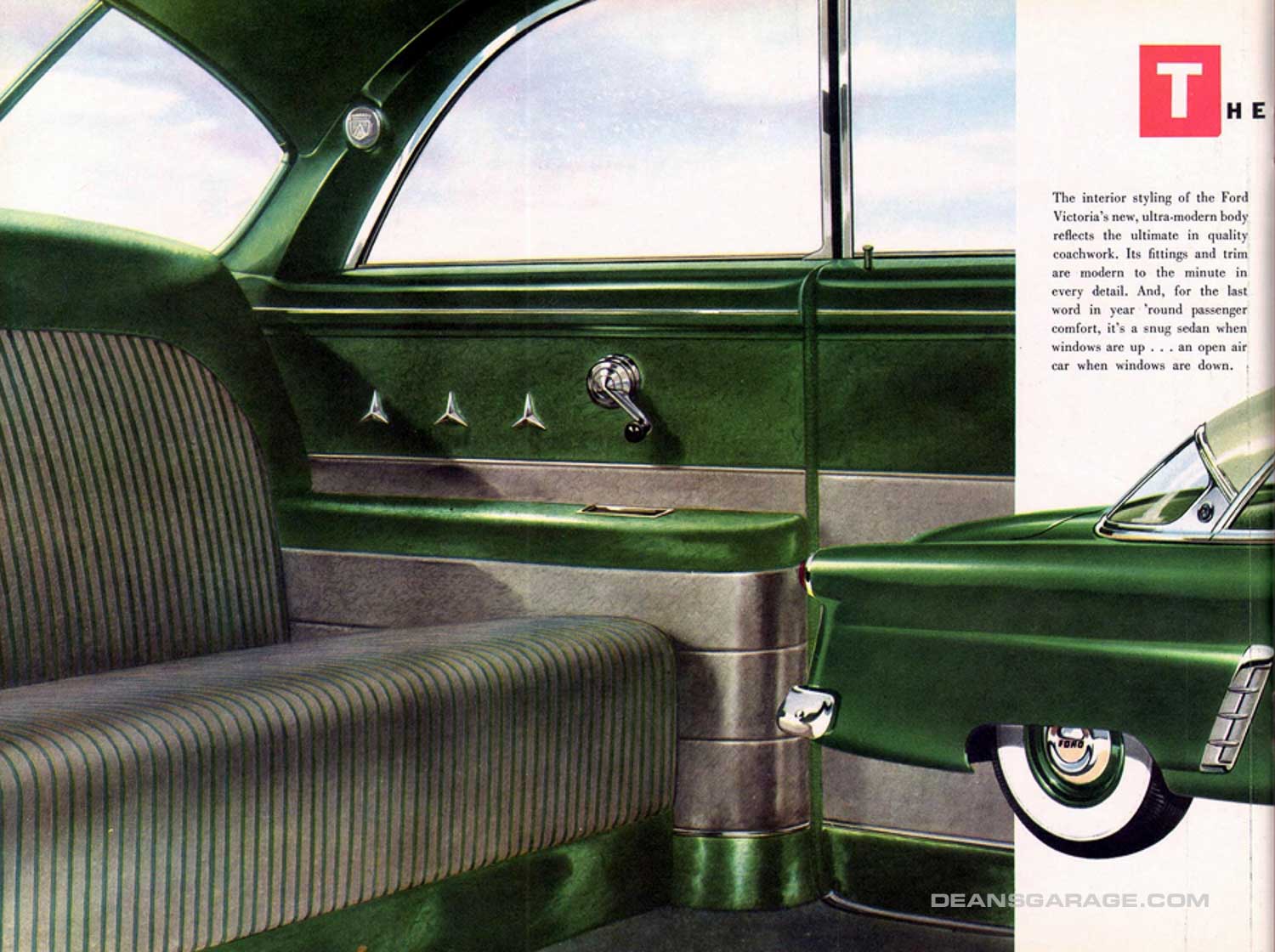

In late 1950, Buehrig was asked to design a new roofline for the ‘51 Ford Victoria, Ford’s first 2-door hardtop-convertible model. The C-pillar design Buehrig came up with for the ‘51 Victoria was also incorporated on the ‘52 Ford Victoria. Buehrig’s greatest contribution to the ‘52 Ford, however, was the all-steel station wagon body he developed. Because of the versatility Buehrig designed into his station wagon proposal, Ford’s station wagon sales went from about 29,000 per year in 1951 to over 50,000 in 1952.

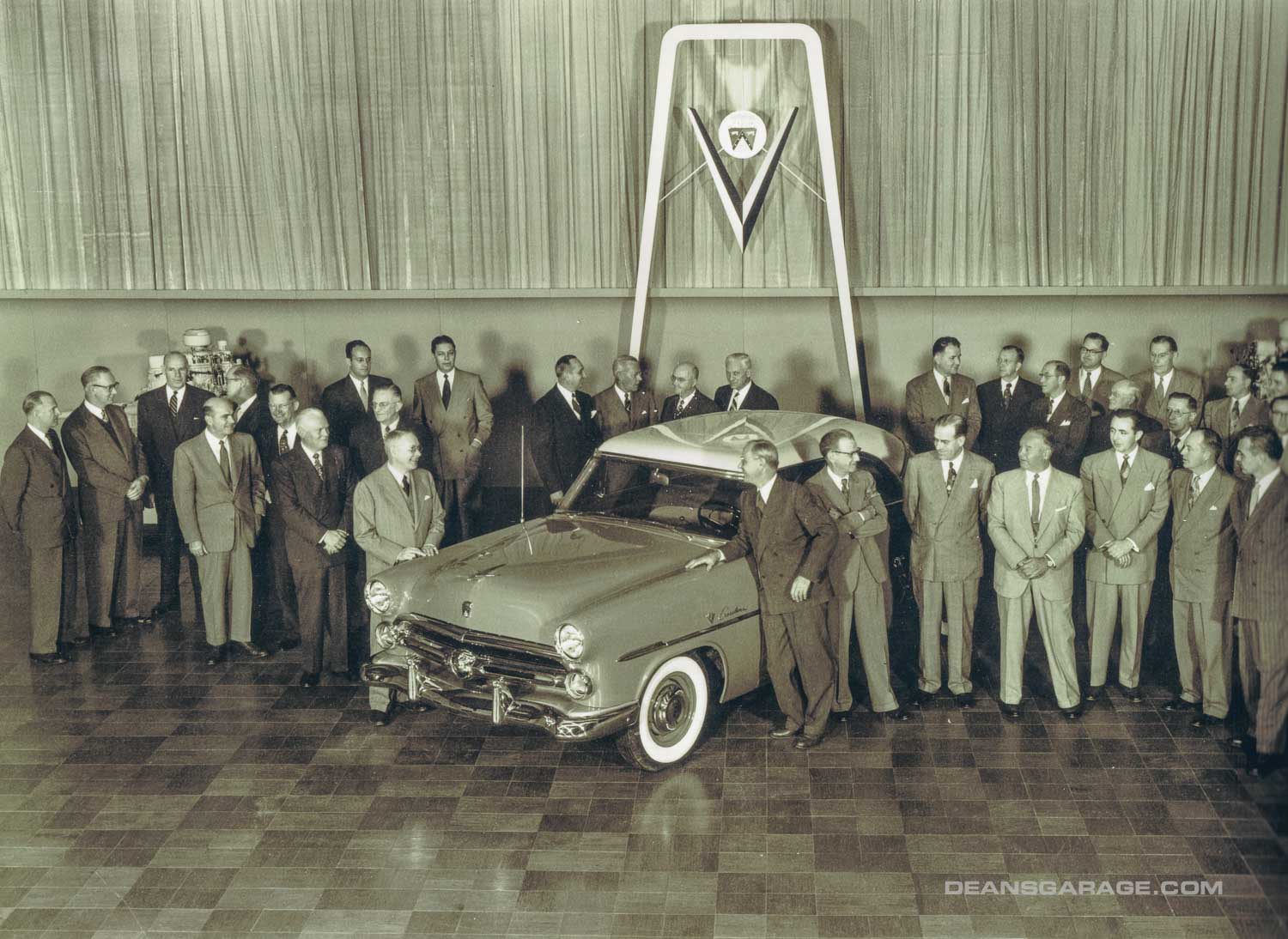

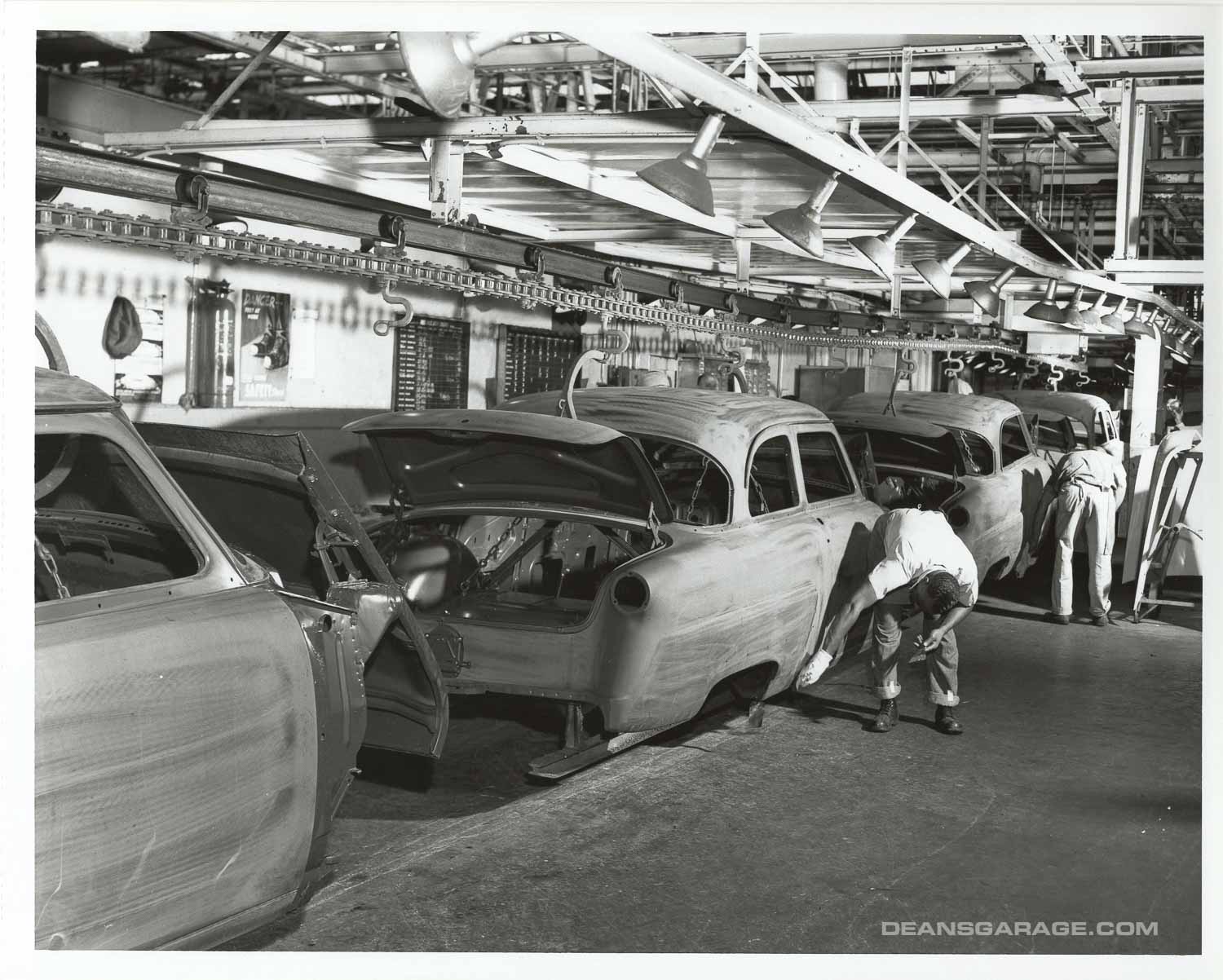

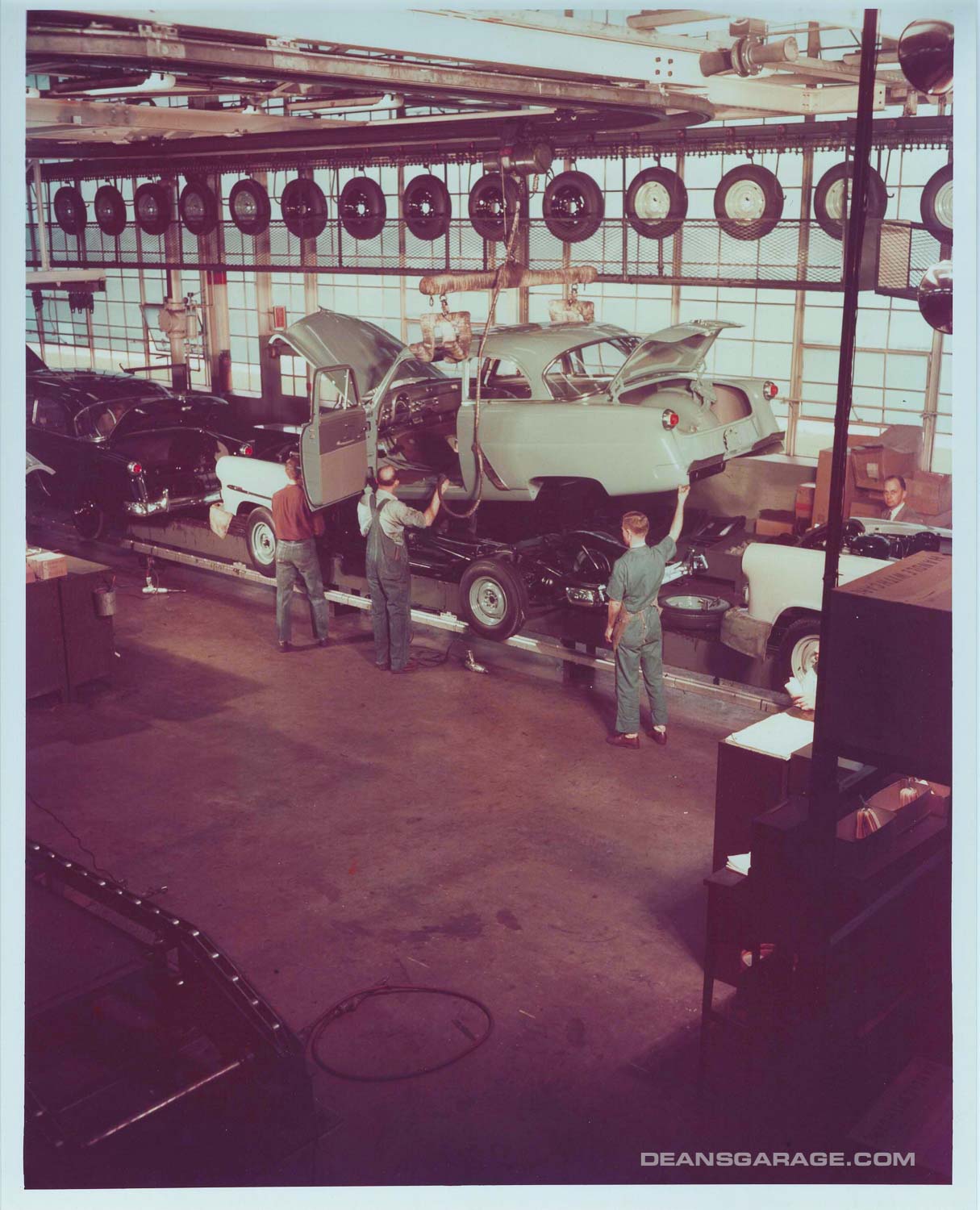

On January 18, 1952, Ford’s 1952 new car lineup was shown to the automotive press, and on February 1, 1952 it was introduced to the general public.

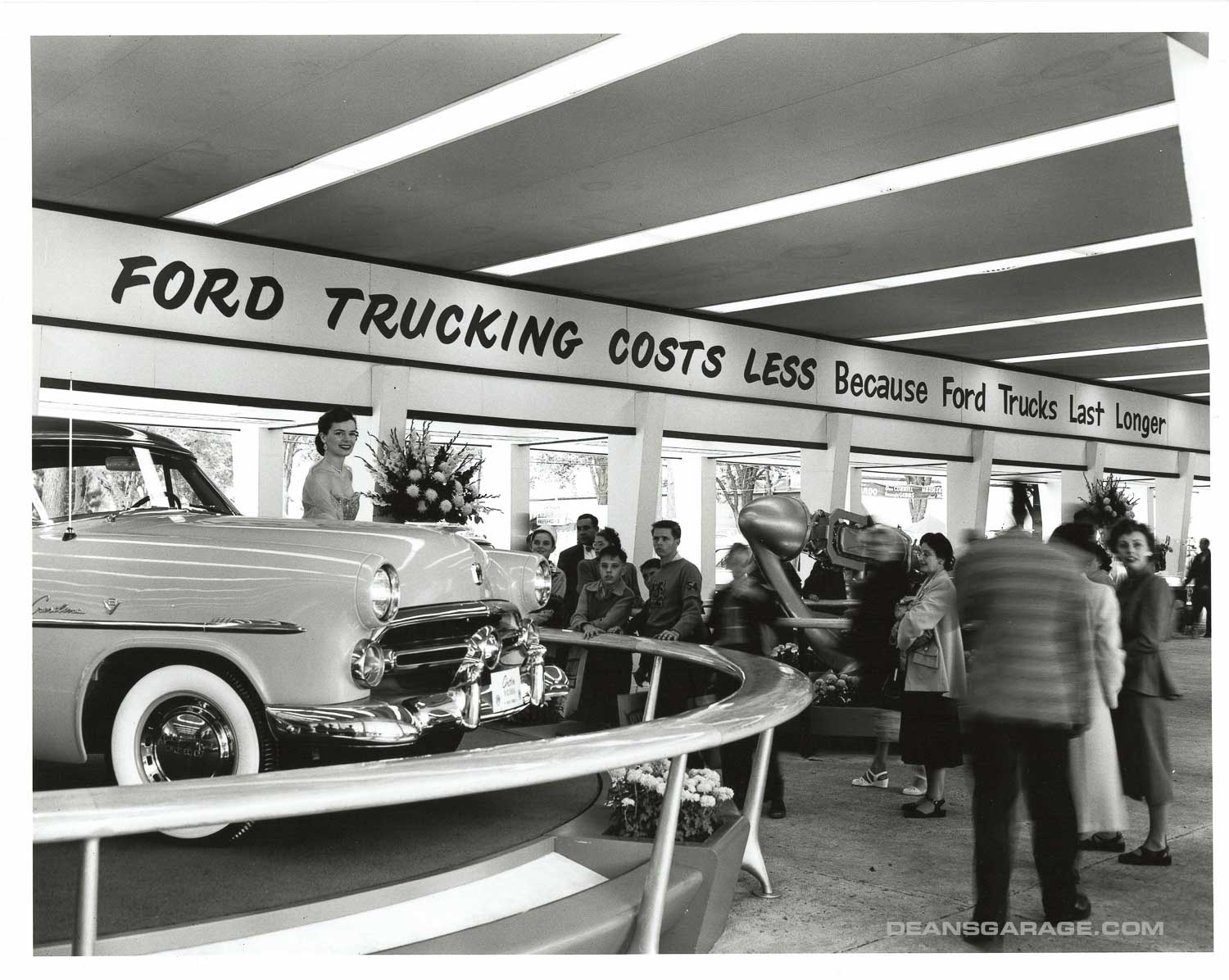

For 1952, sales were disappointing during what turned out to be a severely shortened sales year. 1952 Ford sales totaled 671,733, the worst of the decade. Material shortages because of the Korean Conflict (remember Korean chrome?) were part of the reason for Ford’s late introduction, as well as its general growing pains. By 1953, sales doubled, but it wasn’t until 1954 that Ford sales came within a whisker of besting Chevrolet.

Photos: Ford Design

Books by Jim and Cheryl Farrell

Ford Design Department—

Concepts & Showcars

1999, 10×13, 400 pages, Fully indexed

900 photos. Includes 150+ designers and sculptors, and highlights 100 concept cars.

ISBN 0-9672428-0-0

Lincoln Design Heritage:

Zephyr to LS (1936-2000)

2021, 10×13, 480 Pages, Fully Indexed

1,600 photos and illustrations

ISBN 978-0-9672428-1-1

The Ford book is $50 plus $7 S&H (US). The Lincoln book is $85 plus $10 S&H (US). Both books bought together are $110 plus $17 S&H (US). To order, email: cfarrell57@gmail.com

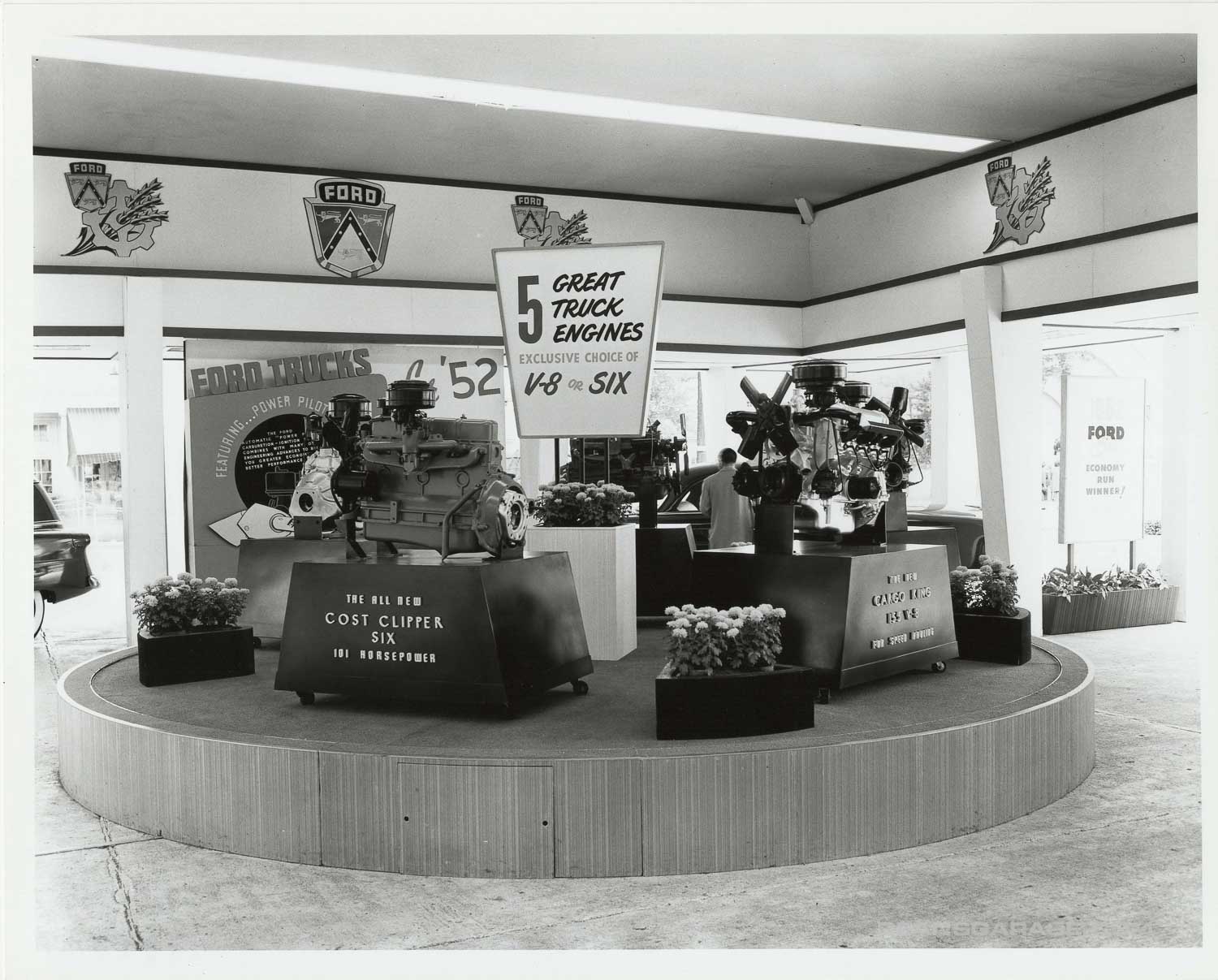

The 1952 Ford’s modern, ultra-clean styling was the talk of the town at annual new-car auto shows around the country!

The 3-piece backlite was used only on the 1951-1952 Victoria. Other makes were still using 3-piece glass in sedans and hardtops. The rapid advancements in glazing technology led to one-piece units industry-wide by 1953.

From these early clays, it appears more talented heads prevailed by the time production of the 1952 Ford commenced.

Thanks for the excellent review on one of the handsomest Fords ever produced.

The 1952 FORDS were a nice new design in their day.

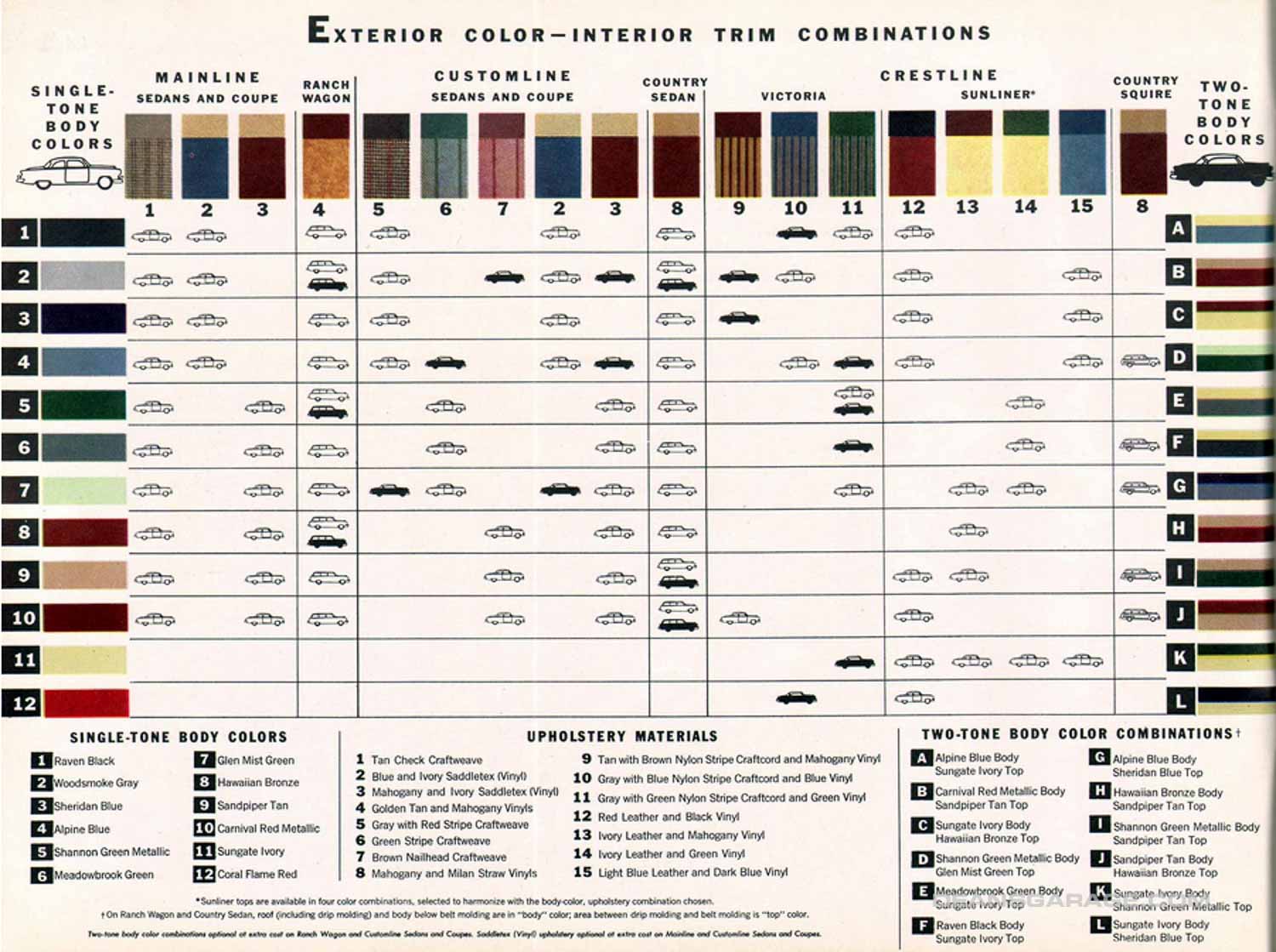

This clean, graceful design made all other US cars look rather dated when they launched! A very good design; they still look quite clean today. Actually compared to the busy, over worked but underdone tortured “designs” of today…….they look VERY good! If one adds the great palette of exterior and interior colors they had vs. the WGB (WhiteGrayBlack) that is slathered on 90% of 2024 vehicles they look even better!

DFO

DFO

Great article Gary! I’m amazed at the research you must have conducted into the individuals who made these programs work ( and those who didn’t…). My dad’s first new car was the ‘53 version of this car-4Door light green with white roof. I learned to drive (legally) in this car in in ‘55 when we lived in Texas where 15 year olds could get a license. I was allowed to drive our second car, a 51 Ford 2dr Business Coupe 6cyl stick. That little coupe would burn rubber for a city block on the crap skinny tires of the day ! ! Perfect for a teen driver!

All well and good but not as attractive as the Shoebox…

If ever a car was misnamed it was ‘the shoe box’. Compared to the ’48, the ’49 Ford might look square, but that’s as far as it went. Compared to its contemporaries, it was anything but a shoe box!

Today at old car shows you rarely see this era Ford as compared to the shoebox Fords. The customizers of the day largely ignored them.

I really liked these cars as a kid, but my favorite was the 1953 Mercury Monterey hard-top. It had “futuristic” elements that spoke to me. When I saw the Merc at introduction in 1952 with the Ford, I knew I wanted to be a car designer!