Me and the Monzas

Or how a young public relations man found himself in the middle of one of the most interesting episodes in the history of the Corvair

by Karl Ludvigsen

From The Corvair Decade

An Illustrated History of the Rear Engined Automobile

by Tony Fiore

Published by Brownell Associates, Sarasota, Florida, 1980

LOC Card Catalog Number 80-66713

Courtesy of James Rice

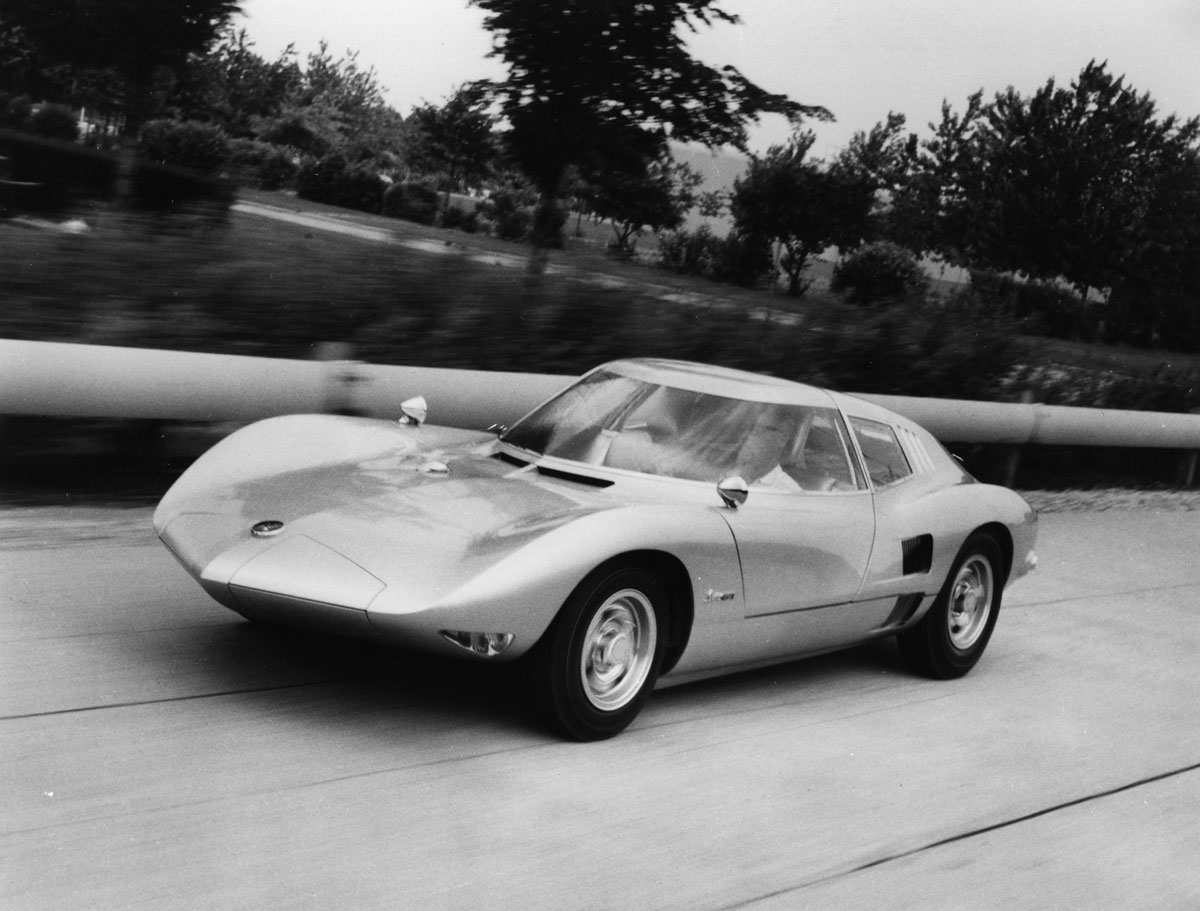

I knew the Tech Center roads pretty well. I don’t mean the Check Road, the mile-long straight next to the railroad tracks with the loop turns at each end that was used for official running tests. I mean the other roads, the ones that most people used to get from Point A to Point B on the big Warren, Michigan facility but to me were as challenging as any section of the Nurburgring. Each had its own characteristics: The S-bend past the gas turbine building, the loop fronting the wind tunnel, and the fast bend around the Styling parking lot—one of my favorites.

On this particular sunny day I was belting along these roads in a dart-shaped silver coupe no higher than a man’s belt buckle. The Tech Center greenery glowed around me and no pillars blocked my view of the road rolling under the car’s sharp nose. It was warm under the canopy and the motor behind me rumbled happily. I cranked the wood-rimmed wheel to the right and the tires chirped as we slid around the long open bend past the working end of the Engineering Staff building—and braked hard to obey the stop sign before the main road. Myron Scott, veteran Chevy P.R. man, goggled from the passenger seat. “So that’s sports-car-ing!” he sputtered. Scotty had discovered what a sports car can do in the unique Corvair Monza GT—and he was as sure as a man can be that he knew all he cared to on the subject.

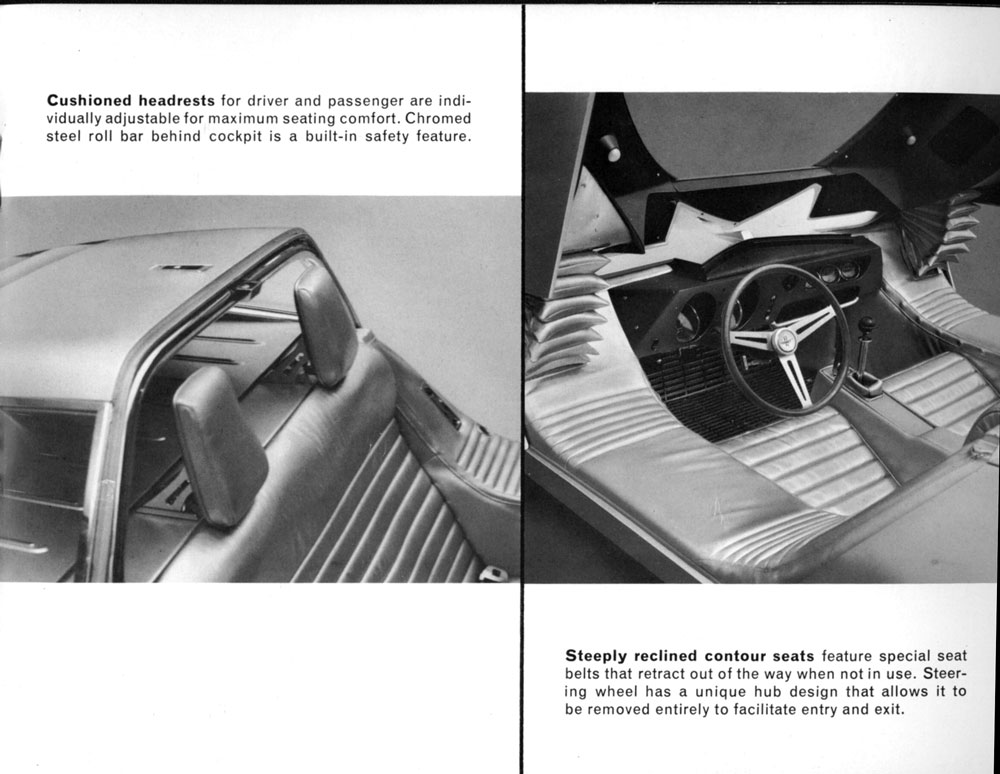

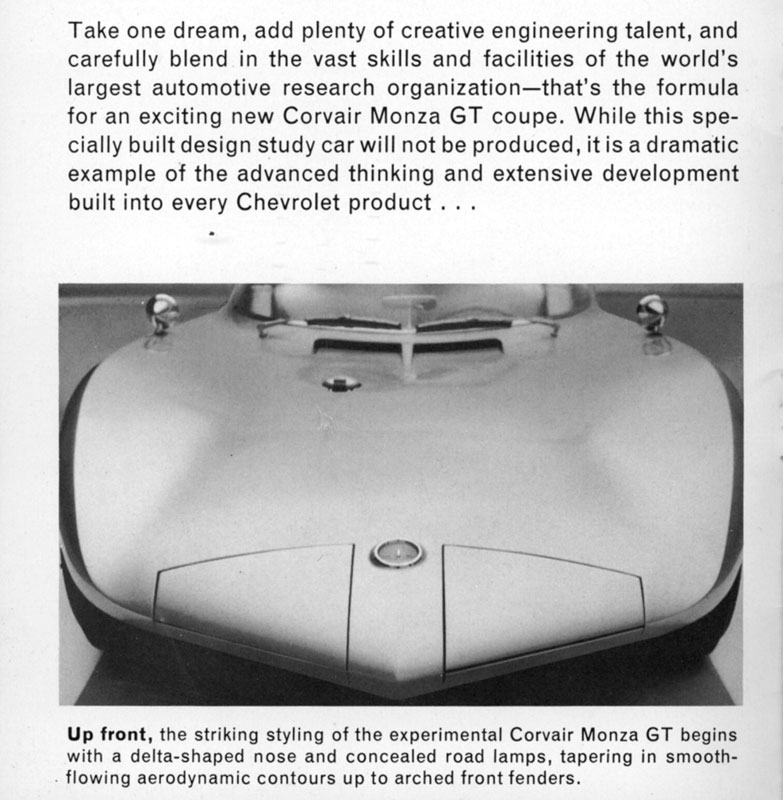

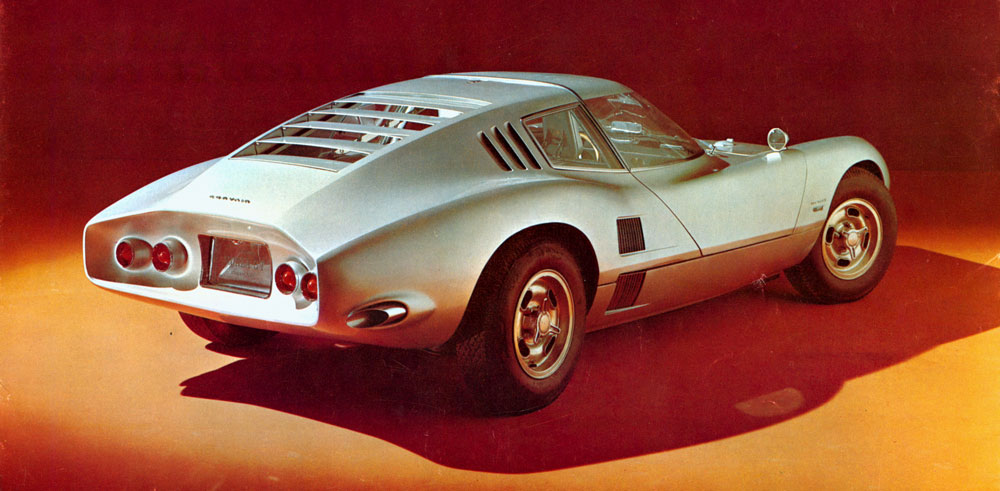

The Monza GT was a super car to drive. It had a thoroughbred chassis designed and built along race car lines. Its mid-placed engine gave it excellent balance. The rearward slope of its seats was radical for 1962, the year of its birth. Leaning back with my head just under the plastic roof, gripping the wheel sloped up at an odd angle from its column, I knew I was driving one of the most advanced cars of its time. And its looks—well, its looks have never been surpassed.

When I joined GM’s Public Relations Staff at the end of 1961, I was assigned to the “Styling beat.” It was my job to help the stylists tell their story. Bill Mitchell gave me the run of the building my first month on the job, and I found a lot of work being done on radical rear-engined sports coupes. This was the beginning of the rear-engined era in Grand Prix racing, and the stylists were spurred by that excitement.

Chevrolet gave them something to work on. Frank Winchell’s R&D group at Chevy was constantly experimenting with new arrangements of the Corvair hardware. They responded eagerly when Bill Mitchell suggested a chassis be developed that was more race car than road car. Bill wanted it to go under a body design that had been created in his private basement studio, under studio chief Ed Wayne, by the Katzenjammer Kids of Styling, Larry Shinoda and Tony Lapine.

The Chevy R&D engineer most involved with the chassis of the XP-777—as it was designated—was Jim Musser. Jim warmed up on these Corvair chassis for the design work he was later to do behind the scenes on the racing Chaparrals. He came up with a monocoque steel chassis, twin-wishbone suspension with torsion bars at all four wheels, and a mid-placed engine for the coupe. He built another chassis for his own tests with the engine at the rear in the normal Corvair manner. A rough-looking test car, this was irreverently dubbed the “Musserati.”

For me as a public relations man, the unveiling of the XP-777 was a nightmare. Public relations people like things to be orderly and programmed in advance. This was never likely with a Bill Mitchell/Frank Winchell project. Probably (though I didn’t know for sure) both had built the car unofficially with chunks of other budgets. So the first appearance of the Monza GT coupe was with no fanfare at all at the Elkhart Lake June Sprints of 1962, driven around the track between races. On such occasions the car was usually driven by Ken Eschebach, the genial sandy-haired mechanic whose task it was to keep Mitchell’s cars running right.

In the fall, we took the GT coupe to the Grand Prix at Watkins Glen. There we couldn’t take it around the track, because ‘Ford with its “Total Performance” promotion had bought those rights for its new rear-engined Mustang roadster—whose debut we helped to spoil by showing off the far more striking Monza GT in the infield. It was my pleasure to explain the car to John Cooper and his team driver, Bruce McLaren. They were fascinated by its clever features.

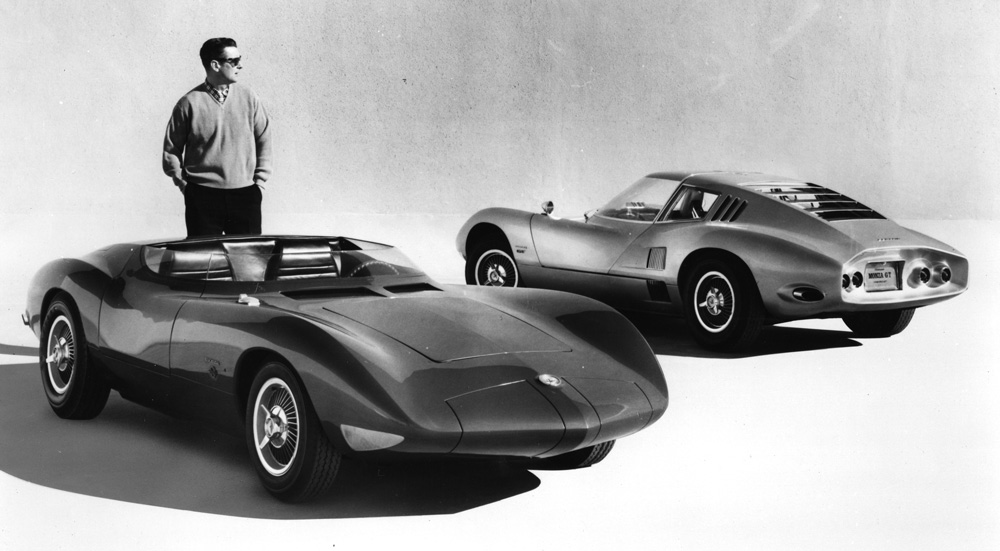

Later in ’62 the Monza GT was sent to California. There it amazed the public at the Riverside and Laguna Seca sports car races. It was also driven to the Los Angeles Art Center School, to be poked and gawked at by the future auto stylists of America. In the meantime, Styling Staff took over the “Musserati” chassis (Jim Musser had built a more advanced toy for testing) and put a roadster body on it patterned exactly after the lines of the coupe. This became the Monza SS. It had a nicer instrument panel and a feature called “theater seats”: lower seat sections that were spring-loaded so they rose up to make it a little easier to settle into this very low car.

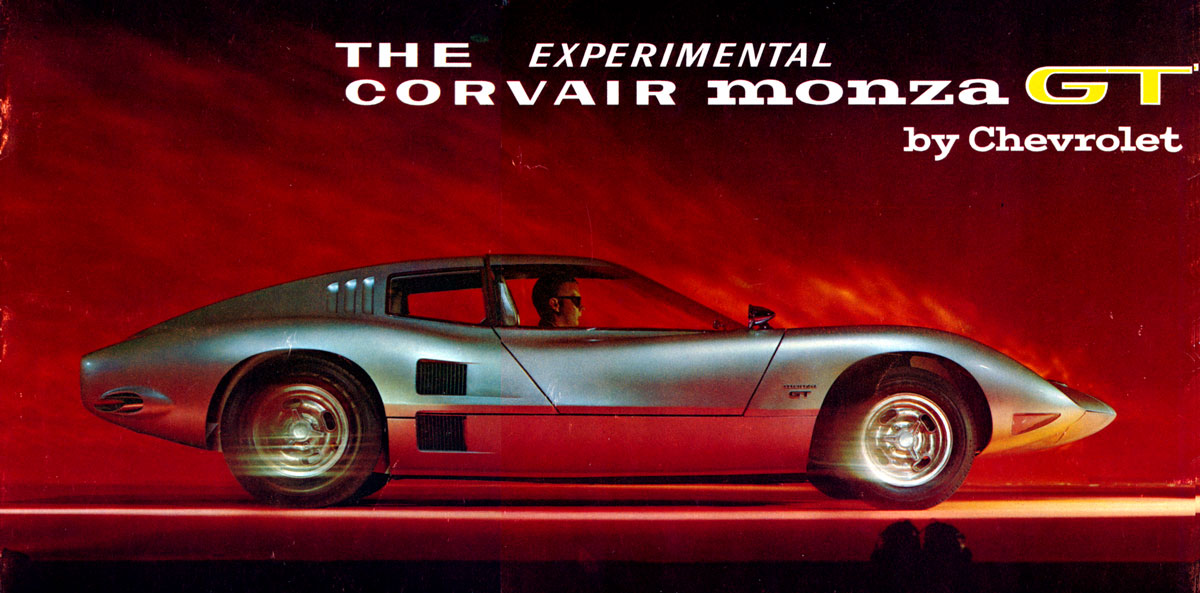

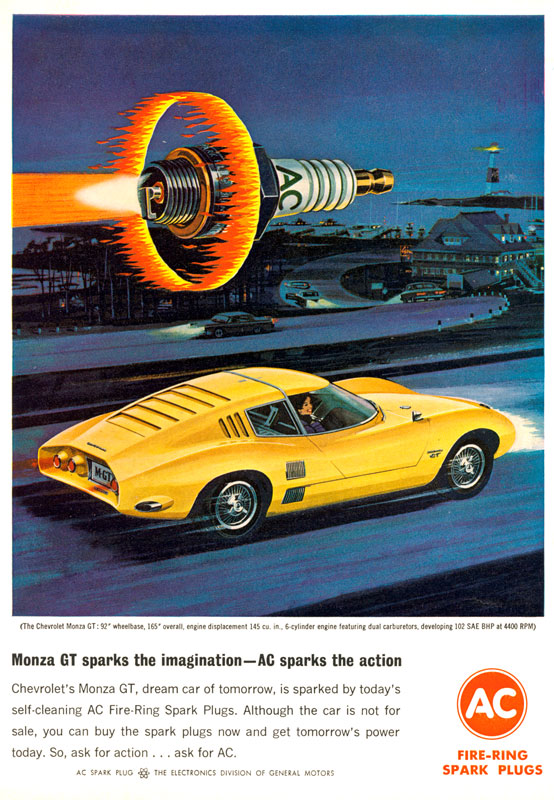

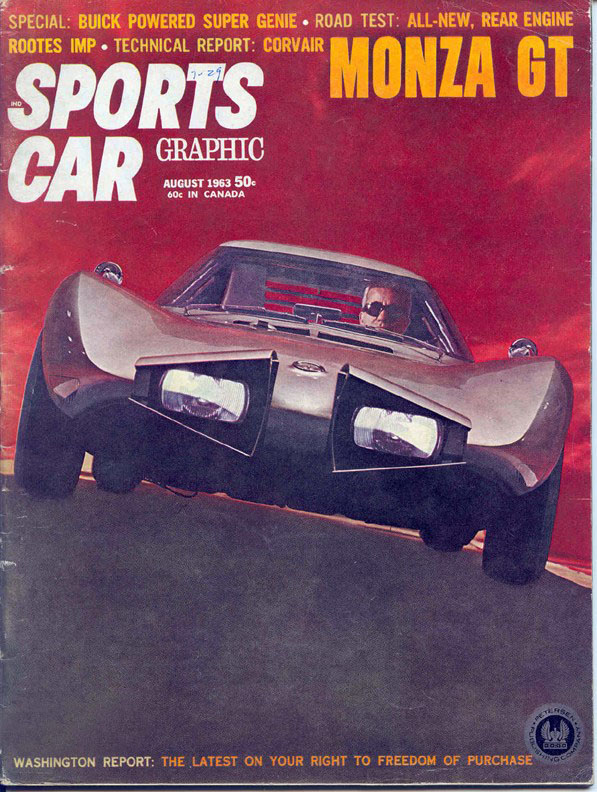

These Corvairs were officially displayed to the public for the first time at the International Automobile Show in New York at Easter time in 1963. At last, as a public relations man, I had a chance to promote these wonderful cars. Walt Farynk and Ed Sperko of GM Photographic reached into their bags of tricks to make dramatic color photos of the coupe that simulated the flame patterns of a re-entry from space. I helped distribute the photos and story material to the car magazines; one of the photos was featured on the cover of the August, 1963 issue of Sports Car Graphic.

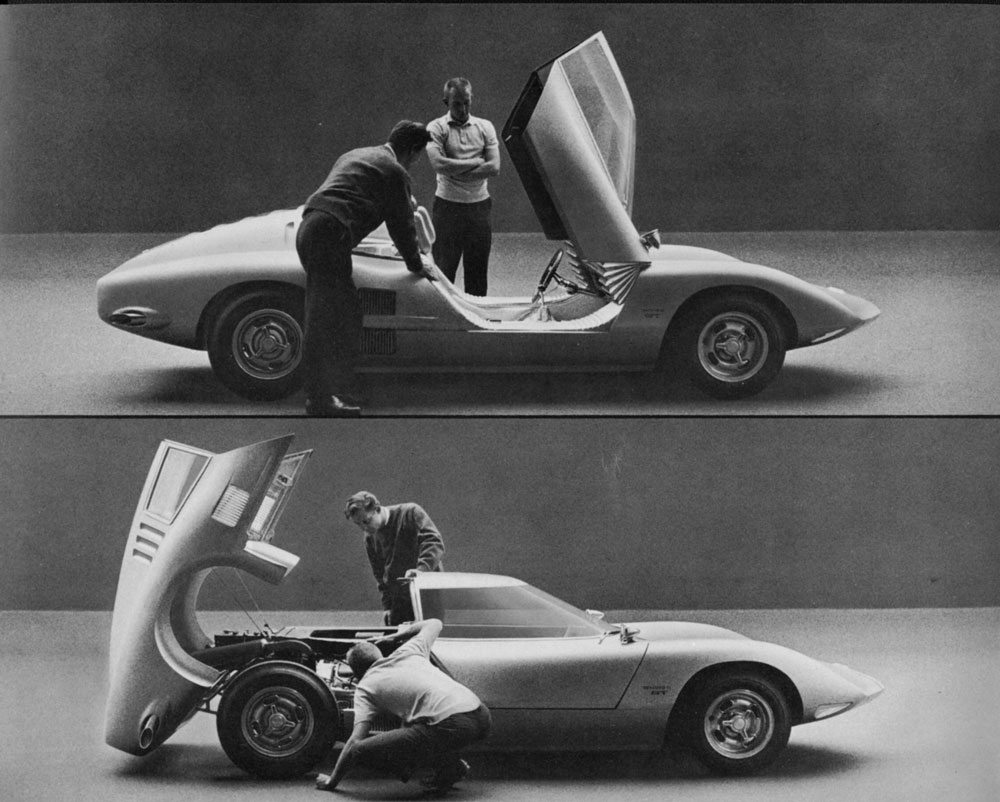

Using these and other photos, Chevrolet’s Myron Scott put together a brochure on the Monza GT for distribution at the New York Show. This gave me my moment in the Corvair sun. Among the pictures Scotty picked up was one showing me peering into the rear engine bay, with rear deck and canopy lifted. It’s nice to be a visible part of Corvair history. (A peculiarity of this brochure is the appearance—certainly inadvertent—of two objects in the right foreground of the cover picture. I’m not sure whether they’re the special lights for the flame effect or a pair of shoes removed by the man sitting in the car so he could walk across the special floor covering in the studio without leaving footprints.)

In the fall of 1963 I moved to New York to go to work for GM’s Overseas Operations Division as press officer. One of my first jobs was to prepare press material for publications abroad on the two special Monzas, which were sent to Europe at the end of 1963 to make the rounds of the major auto shows. I arranged for special photography of both cars, including shots of the two of them together at the Tech Center with a blonde model. One of these photos appeared on page 108 of Volume II of Automobile Year.

We also arranged for movies to be taken of the cars while they were in Europe. It seemed to me at the time that there was a reasonable chance that a car based on the Monza GT or SS might go into production. So we’d be covered for that possibility, I arranged for movies to be taken of several stages of its development: fabrication of the coupe body, tests of the “Musserati” at the Tech Center, and those shots of the two cars on the road in Europe. Not long ago I tried to find out if any of the film still exists, without success.

Chevrolet did consider producing a version of the Monza SS roadster. A photo of the revised edition, with bumpers and a full windshield, that was proposed for manufacture appears on page 400 of Volume 8, Number 4, of Automobile Quarterly. As we know, however, it didn’t happen. Instead, the two special Monzas left us brilliant memories of the sportiest Corvairs and absolute proof that if Chevrolet ever did want to produce a fine small sports car, its designers were more than ready to oblige.

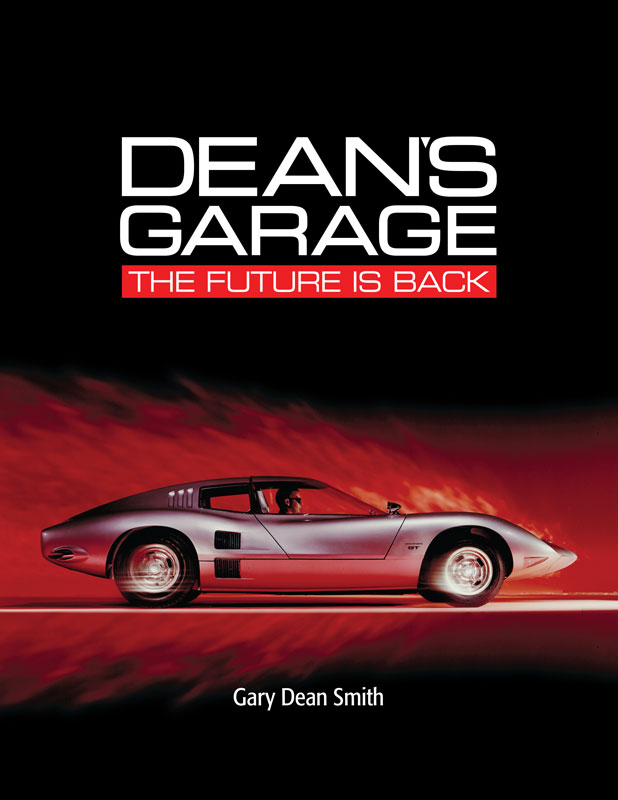

Had I known about this well-written article that brings to light several factors about the Monza GT that have puzzled me, it would have definitely been in the Dean’s Garage book.—Gary

Karl,

What great memories! A great article.

Another design / styling subject is the influence of the Monza GT on the design of the closely followed Italians, the Lamborghini Miura and the De Tomaso Mangusta. Gandini who took the project over from Giugiaro at Stile Bertone after he left claimed that it was very influential in the design of the Miura, obviously the proportions, size, backlite louvers and other details.

On th Mangusta, the rear quarter louvers let air into the engine compartment, on the Monza GT they appear to me to provide a little added visibiliy for the driver.

The 1963 Stingray came out shortly before the Mangusta was designed on Giugiaro’s kitchen table and it appears that the Stingray backlite divider gave Giugiaro inspiration to justify the lifting rear engine covers with a fixed hinge pillar between them, creating a rear vision interference like the 1963 Stingray. There is no doubt that the 777 was a very influential design on both.

The design was strong enough that it was not a negative to be influenced by the 777, it would be a appreciated as a positive design influence. In reality there were design choices taken on the 777 that were also correct for the other mid-engine designs that followed.

Another design that had a strong influence was the very beautiful racecar done at GM Styling the 1957 Corvette SS that raced at Sebring. The design of that car is credited to Harley Earl, giving new value to the breadth of his car design abilities and scope. It came out at a significant point in the creation of the Jaguar XKE which debuted in 1961. Assuming it would be the new Corvette inspiration, Jaguar was apparently very impressed and probably felt that it would be the significant inspiration for the new Corvette also. The XKE has many design features seen on the SS. The louvered fighter aircraft-like hood, the skirted rear wheel, the long dash-to-axle and rounded front fenders . Also the covered headlamps and portruding rounded grill, fill in the intersection between them and you have the XKE front corner, even the plan view would be similar. The hood inner structure and front wheel baffel on the XKE is also very much like the SS. The way the hood swung open was on race cars of that time and like the 777 and the SS and the surface that bridge the hood and the body side at the base of the front windshield corners are very similar on the XKE. The latches to unlock the front hood on the original XKE’s are also seen on the SS.

Thanks for doing that article.

DICK RUZZIN

There have been many, many great “might-have-been’s” in GM’s history, but the Monza GT/SS story is one of the best and saddest. While Ford was trying to push that Taunus-powered (i.e. underpowered) Mustang, Chevrolet had essentially a Porsche GT3 in 1962. Think about that. Even with an atmo Corvair engine (200 hp?) it would have been sensational. With a really worked turbo (or the rumored-but-never-seen OHC engine), well…

A great story. Two great cars. And two stories that should have read much differently. Manufacturers built “halo” cars, and this should have been Chevrolets – and GM’s.

What a great article and concept car. I remember it well and it inspired a boy growing up in New Orleans who wanted to be an auto stylist when he grew up. I wonder if the front end design influenced the Jim Hall Chaparral, another great car.

BTW, I made it to Detroit 20+ years ago but as a Landscape Architect and I still love cars and auto design.

Thanks for the article. This car is my absolute favorite show car, a truly great design. I was an Art Center design student when Mitchell brought it there to show the graduating class. We were all amazed at the car. When it was driven to the front driveway at the old Art Center building, the ramp was so steep that it was driven slowly at an angle with the canopy up so the driver could be careful not to scrape it. As a Corvair owner/fan, I dreamed of buying the production version, but I heard that it was considered too expensive (to produce or retail price???) to offer it for sale. It’s as beautiful today as it was then.

Ah Karl, memories, memories. I had two Corvairs – a 1961 Black Coupe with a manual and ac bright Red interior and a 1963 Convertible in light metallic Green. I sold the convertible when my wife did a 360 in the winter on Adams Road and would never drive the car again.

The Monza’s were great cars and to Mitchell’s credit, they finally arrived when the Monza production model was introduced. Small detail about the organization of Studio X, Larrry Shinoda was the designer, Tony Lapine was the Studio Enginerr, and Ed Wayne was the board man or Tech Stylist. I do not believe there was any rigid organization and Mitchell was actually the Chief Designer.

BTW #1, when Harry .E came into the studio, he always said to Shinoda, “ Japanese women are like this” and he would extend his flat horizontal hand and move it horizontally. Shinoda would respond, “No , Japanese women like this” – and he made a vertical motion with his vertical outstretched hand.

BTW #2 – Karl, remember the SEA meeting and your topic “Sports Car Shape and Structure”?

Ah, memories!

Ken Pickering