The First Stingray

Published in Car Classics, October, 1977

Story be Rich Taylor

An interesting account of Mitchell’s Stingray racing effort with quotes by Mitchell and Kenny Eschenbach.

It goes without saying that Bill Mitchell was not unanimously popular when he took over GM Styling in December 1958. Harley Earl had literally invented styling at GM, he’d run it with an iron grip for 42 years, the system was set up with Earl as the final arbiter of all decisions. But there was no established procedure for succession at Styling, for the simple reason that there had never been a change at the top. Bill Mitchell wasn’t the only stylist who thought he was capable of replacing Harley Earl.

On top of which, Mitchell can have an irritatingly overbearing personality when he wants to. He goes out of his way to prick over-inflated egos, yet his own hubris is of monumental proportions. He is also a firm believer in shock tactics, in the vein of the old P.T. Barnum dictum-’ ‘it don’t matter what they say about you, long as they spell your name right.” Not everyone in General Motors was convinced that Bill Mitchell was the right choice for Styling vice-president of the largest corporation in the world.

But Mitchell was Harley Earl’s chosen successor-had been for years-and he moved quickly to establish his own power. A definite break between the Earl Era and the Mitchell Era occurs between the 1960 and 1961 GM models. Mitchell had no desire to carry on Earl’s motifs. Indeed, he wanted to get his own style onto the cars as quickly as possible. He wanted people-both inside and outside of General Motors-to see that style, and to know that there had indeed been a significant change. And he wasn’t willing to wait for three years while the production cars caught up with the new management. Mitchell needed a car that would be undeniably his, undeniably new …and be ready overnight.

The Sting Ray was the answer to all Mitchell’s problems. In 1957, Larry Shinoda and Mitchell had worked on a startlingly angular styling study called the Q-model, which they proposed for the 1960 Corvette. lt was peremptorily voted down. But Mitchell isn’t one to give in easily. He talked to Ed Cole, and in the fall of 1958, even before he officially succeeded to Earl’s vice-presidency, he . was allowed to buy the chassis of the first Sebring SS.

This wasn’t the SS that so embarrassingly broke after 23 laps in the 1957 Sebring 12-hours, but the SS “mule” with which John Fitch, Piero Taruffi, Stirling Moss and Juan Fangio had practiced. The mule had been completely rebuilt after Sebring, in the winter of 1957, in order to bring it to Le Mans-but the Automobile Manufacturer’s Association ban on racing killed that project.

Zora Duntov, whose Corvette engineering group had built and maintained the SS racers, salted away his suddenly obso lete racing cars in a Styling warehouse where they weren’t doing anybody any good. Mitchell bought the mule for a dollar-against Duntov’s wishes—with the written proviso that whatever racing it did would be done on Mitchell’s own time and money. There would be no Chevrolet or Corvette emblems on the car. As far as General Motors was publicly concerned, it was just a personal hobby of Mitchell’s.

Of course, the fiberglass body that Shinoda designed was built in the GM Styling shops. The idea was that the body would have a flat top and a rounded bottom, which would make the entire car behave as a huge, inverted airfoil for better road-holding. This whole concept was fallacious from the beginning. The rounded nose provided incredible amounts of lift, not down-force. At high speeds, the car was nearly uncontrollable.

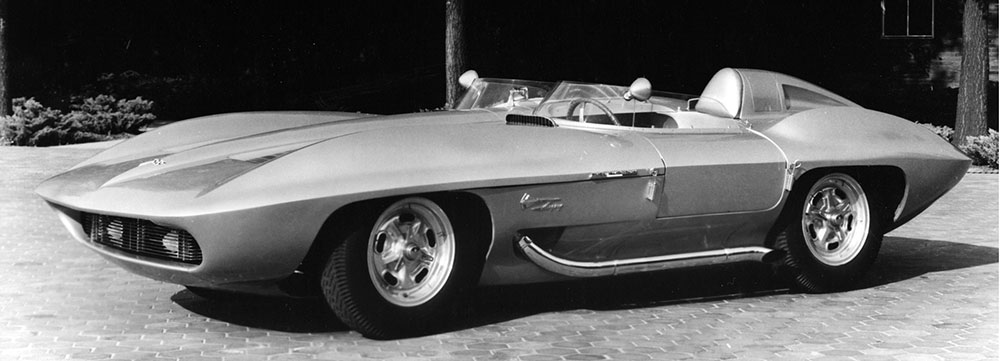

But it was beautiful. Shinoda’s Sting Ray-which, of course, became Mitchell’s Sting Ray-was clean, modern and functional, without any of the styling excrescences that made the Sebring SS a caricature of a racing car. The high belt line, the subtle fender bulges, the squared-off wheel openings, the full-width grille, the carefully integrated headrest were all fresh, innovative touches in 1959. When it first appeared, the Sting Ray got as much publicity as any racing car in history…which, of course, was the point of the whole exercise.

The chassis, except for minor revisions like an aluminum radiator and new headers, was the same old SS mule, complete with a birdcage-type tubular space frame, DeDion rear axle with in-board drum brakes, Halibrand wheels and a fuel-injected, big-valve aluminum head 283 V-8. Mitchell had it painted bright red and shipped to Marlboro, Maryland in April 1959. Dr. Dick Thompson, the Washington, D.C. dentist who had already graduated from Austin-Healeys to become the best known East Coast Corvette racer, had his SCCA license suspended for three months due to the antics of the Sting Ray at Marlboro. The nose lifted at speed, and the split-system brakes—which were the weak point on the Sebring SS—continued to lock up unpredictably. Thompson was beaten only by a Lister-Jag and two RSK Porsches, but the car had been dangerously all over the road.

After Marlboro, Mitchell realized that it takes more than a car to go racing. He enlisted Dean Bedford from Corvette Engineering and Ed Zalucki from Zora Duntov’s staff to help out. Mitchell rented a small shop in Roseville, Michigan. He assigned Kenny Eschebach, a mechanic who worked—and still works—in GM Styling Special Vehicles, to be the part-time crew chief. Eschebach split his time between GM and the Sting Ray; Dean Bedford and Ed Zalucki were paid overtime to come in evenings and weekends to do development work.

Except that everyone involved was a Tech Center employee and had access not only to incredible parts supplies but also skilled workmen and professional shops capable of turning out almost any part one could need; except that the car was a GM Styling idea car—the Sting Ray effort was run like any other amateur racing team.

Says Mitchell, “My agreement was that I’d keep it off the Tech Center property, and spend my own money to run it. It cost me quite a bit, too. I financed it all out of my own pocket. I couldn’t afford to do it that way today. But it pleased me no end to go up against Cunningham and those boys with the faster cars, and take any of them.

‘’The Sting Ray would take a D-Jag…it’d do zero to 60 in four seconds. We started with the original fuel injection, we tried four Webers, and different cams. The only weakness it had was the brakes. They never did work right, even the Chrysler center-plane power brakes we ended up with at the end. I always liked the looks of the Sting Ray. It was very photogenic…see that strong shadow underneath? I always liked that.”

Kenny Eschebach was the only person who lived with the Sting Ray day to day for the full two years it was raced. He says, ‘’It was like any race effort. There was always too much to do. But considering Mitchell was paying all the expenses, it was pretty professional. We never had a four man crew, as we should have; we didn’t have adequate time to make our changes; we never had enough good help. It was the same old story…first of all the looks, then the mechanics of the thing. Every time we went to a race we had to repaint the whole car, but it took us two years to get decent brakes.

‘’But everybody wanted to be in on the race car. I remember at Danville, Virginia, we had a guy come with us to help, and just before the race, he decided to tighten up everything on the car. We had the race won, and two laps from the end one of the copper fuel-injection lines split where he’d over-tightened it. That kind of help I didn’t need.”

‘’The race team was Dean Bedford, Dick Thompson, Thompson’s wife and me. Mitchell usually put in an appearance every other race or so. We were never overdogs—people never resented us, as far as I know. If we had come in with a big racing team, with all the equipment and all the people, then they wouldn’t have liked us much. But we let it be known that this was strictly a small group, that we were doing this on the side. We weren’t coming in with a factory team or anything, remember. We raced just like an individual would race. The Jaguar team, the Maserati team, the Momo group…they used to come in there with all sorts of equipment, a machine shop and everything. We never had that.

‘’Tight tracks were no good for us. All the Corvettes had a tendency to plow, and the brakes weren’t very good. We were better on the fast tracks: Meadowdale, Danville. The chassis had been engineered for Sebring, don’t forget. We could handle well enough, and take the Porsches down the straights. The RSK was the car to beat; they couldn’t out accelerate us, but their handling was so much better, they could out corner us. They were our main competition on the tight tracks. On the fast tracks, the Birdcage Maseratis, the Meister Brauser Scarabs of Pabst and Heuer were the big guns. But we could stick with them.

‘’The big mistake we made was not going to disc brakes as soon as we had trouble. But Dean Bedford was a very strong-minded individual. And he was in charge. He had engineering control. I had to listen to him. And he was trying to prove a point, to make those brakes work.

“We tried all sorts of things. We started with cerametallic linings, but that just chewed the drums up. Then we went to a sintered lining. That worked all right for a lap, but you couldn’t get rid of the heat. Neither one of them were any damn good. Finally, we tried cast iron inserts into aluminum fins for the brake drums. That worked good, the best thing we had…we could almost make it all the way through a race. It got rid of the heat. Now of course, the car has discs on it. But it took them a long time to learn. It took the whole corporation a long time to learn about brakes.

‘’We didn’t have any problems in the go department. When it was first completed, with the 283 engine in it, the car would go 180 miles an hour, provided you ran a 2.80 rear axle ratio. Generally we ran a 3.27, a 3.70, or a 4.0, depending on the track. Even with that gear, it would still go 150 miles an hour. It wasn’t like a production transmission. With a 3.70 axle, we could still do zero to 150 miles an hour in about l7 seconds.”

The Sting Ray’s first race was at Marlboro in April of ’59; its last appearance was Laguna Seca in October 1960. ln that short period, the car went through numerous engineering changes, acquiring a locked differential, three different sets of brakes, a completely new, light weight and flexible fiberglass body, a silver paint scheme in place of the original red and a matching silver leather interior. The weight was reduced to under 2000 pounds, the rear end was shimmed up to help the aerodynamics and road-holding.

The Sting Ray more than achieved its goals. Important, but relatively peripheral to the main discussion, this car and Dr. Dick Thompson were the SCCA E-modified National Champions in 1960, handily winning almost three times as many points as the next team. For Mitchell, winning was an important thing, but it wasn’t the only thing. Thompson’s win earned the Sting Ray more publicity than it would have had otherwise, particularly in the enthusiast press. But most important, the Championship gave the Sting Ray—and by extension, Bill Mitchell—credentials around GM.

Mitchell had put an idea-in which he passionately believed—to a real world test, out in front of everybody. At a time when GM corporate was afraid of making fools of the company by failing at the race tracks—as they’d done with the Sebring SS—Mitchell was willing to put it all on the line. His car won races, and a championship. But even better, it won over whatever critics he had on the fourteenth floor. The Sting Ray, in short, established Mitchell as the unquestioned chief of General Motors Styling, so that when it came time to restyle the Corvette, there was no debate over what shape that car would take.

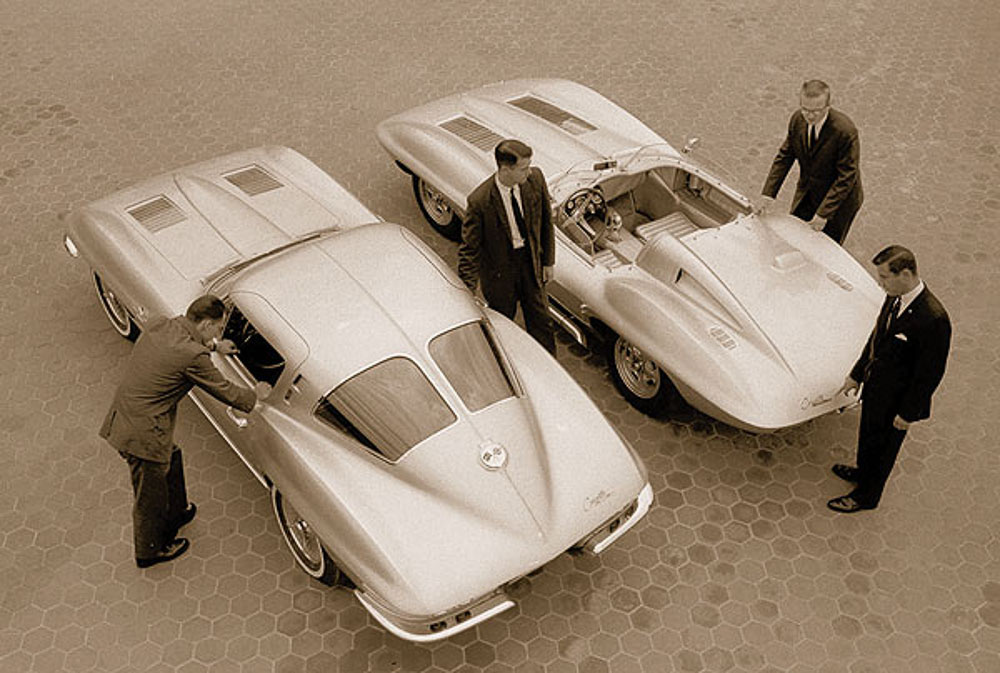

Clare MacKichan was in charge of the studio that produced the classic ’63 Corvette, but all the lines were lifted, literally, off Larry Shinoda’s racing Sting Ray—even to the extent of developing the first hidden headlights so that the distinctive, sharp-prowed Sting Ray nose could be preserved. And even though Dick Thompson had proved that the Sting Ray shape was aerodynamically unsound, it was kept for the production Corvette anyway, because Mitchell liked the looks. The battle over the Sting Ray shape—particularly the hidden head lamps—pitted Mitchell against Zora Duntov in a classic contest between stylist and engineer. That Mitchell won handily is just the final proof of how much his power had been consolidated in the two years since Harley Earl had retired.

Of all his hundreds of cars and show cars, the Sting Ray is Bill Mitchell’s personal favorite. lt’s perhaps the best looking GM sports car ever: purposeful and masculine, devoid of the busy, effete effects that mar lesser machines from the Mitchell Era. And unlike the other GM showcars, the Sting Ray, with its racing history, has real world credentials. It’s also a one-off, so it’s much more valuable arid unique than any production car could hope to be. And the best of all, it’s a consummate machine, a marvelous totality that seems right and proper from any angle, body on or off—mechanically, aesthetically, however you want to judge it. The Sting Ray, in sum, is the distilled essence of everything Bill Mitchell—and GM Styling under his direction—has represented for two decades. It’s the quintessential Mitchell machine.

We always referred to it as “the Original” Sting Ray, to separate it from the somewhat underwhelming production car. Funny also that the production car shared the same major weakness as the race car, inadequate brakes. The XKE had shown up the year before with 4 wheel disc brakes, as had the previous XK150. But the race car was considered a junior Scarab, which it really wasn’t. But boy did it “look” like a race car. Wow. So what we always wanted was a street race between the street-driven Scarab and Mitchell’s Sting Ray. They were both licensed vehicle, right? And wasn’t there a clear “hardtop” for the Sting Ray like the one for the SS and other concept Corvettes?

The only flaw in the Sting Ray styling is the headlights. No C-2, C-3, C-4 or C-5 Corvette looked great with the headlamps exposed, plus the hidden headlights mechanisms added unnecessary complexity and weight to the front center / quarters of the car. Yes, the C-2 was a trend setter, but by 1968, the hidden headlights were a gimmick.

Was not the basic shape of the Stingray and the 63 production car originally, basically proposed by Mr R. Cumberford and then brought nearly to fruition by Mr Peter Brock? Seems from my reading that those two were really the genesis of that shape, finalised by Mr Mitchell and Mr Shinoda.

What a great article…. Historic.

The 1963 Stingray underwhelming??? Are you kidding?

Pete Brock’s original sketch is the seed that led to the Stingray, Mitchell liked the Disco Volenta and Pete was able to evolve that seed into a design that could be visualized as much more. And to Mitchell’s great credit he recognized the theme’s greatness and stuck with it.

The 1963 hidden headlights were clearly worth the touble as the whole design would have to be different without them. When the car came out it was a sensation, still is. It is almost sixty years old! Turning the race car into a street car requires a lot of design skill. Regarding the aerodynamics, it was mostly black art then.

On the track with the competition, they were all design inspired by the Europeans and the Stingray was clearly an American design that really stood out. Jaguar must have thought that the SS was going be the next Corvette and the XKE shows many of it’s design influences. The Stingray is a unique and flexible design statement that is very well executed, few of that era come close. The Ferrari 330 is also outstanding but it looks back. The Stingray clearly looked forward.

I think that the most significant thing about it, after the chosen theme, is the execution of the shape. It is very artful in character, a consistant form language that makes it right from any view. Two very outstanding design features.

Dick Ruzzin