The Ford Mustang Was Conceived By…Shhhh…

by Trebor Crunchog & T. Tom Meshingear

Yes, the most successful new car of all time, the Mustang, was thought up, preliminarily dimensioned, presented to management… and brutally rejected in 1956. It came from Studio X at the General Motors Tech Center in Warren, not from Dearborn, where Ford profited mightily from the idea.

Here’s a brief timeline. In 1955–56, Robert Cumberford, then 20 years old, was working in the Chevrolet Studio. One day studio head Clare MacKichen told him to go to Body Studio 5 to work on the next (C-2) Corvette under the direction of Chuck Jordan, who had made a reputation for himself with a front wheel drive Motorama show vehicle, the GMC “L’Universelle” panel truck. It was an unpleasant assignment, even for a sports car enthusiast like Cumberford, because there was no studio staff, just Jordan and himself. Jordan spent most of his time outside the studio, polishing apples and working on company politics, so it was lonely work.

In those days, GM stylists made sketches and put them up on vertical drawing boards. The boss would remove things he didn’t like, fold them up and put them in the shredder bag, thereby giving indirect guidance to studio designers. In the Chevrolet or other brand studios, with at least five or six stylists each, that worked fine. Jordan didn’t draw in the studio, but he did bring in drawings from home, sketches done on his kid’s blue-lined notebook paper. “I just can’t stop thinking about this project and work on it at home,” he explained.

One day while taking a look at those drawings, Cumberford noticed that some were really rough copies of some of his own sketches which had been removed. Giving that observation some thought, he said nothing, but began making sure that every other sketch he did included some feature that he knew, after almost two years at GM Styling, that at least one member of Harley Earl’s “Design Committee,” a four or five man cabal of “Yes” Men, heartily disliked. Those he posted, usually 8–10 per day. But every other drawing he put aside in his taboret. A prolific sketch artist, Cumberford only did black and white pencil sketches, no color, no renderings at all, so half his daily output still was adequate to satisfy Jordan.

After a while all of Jordan’s ever-renewing copies and all of Cumberford’s posted originals were almost certain to distress Earl and his followers. One day, Earl and his group entered the studio with Jordan. Earl looked at everything, clearly dismayed by what he saw. “Well, now, Chuck, uh, what if we, uh, took a little of this front end and a little of that over there, and well, uh…”

Lower level personnel were never supposed to directly address Earl, but working up his courage, Cumberford fumbled out of his taboret a sketch very much like what Earl was asking about. “Like this, Mister Earl?” Startled, Earl snapped, “What’s your name, you?”

“Bob Cumberford, sir.”

“Well, Bhwab, you have any more drawings in that drawer?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, why aren’t they up on the wall, Bhwab?” he asked in a menacing tone.

“Oh, I take my direction from Mr. Jordan, sir, and you can see over there on the left the things he likes.”

Nothing more was said, and Earl, the Committee, and of course Jordan left the studio.

The next day, when Cumberford came to work, the pistol-toting guard in the loading dock where the working staff entered from the parking lot said “You. Don’t go to Jordan’s studio, go see MacKichan.

“Morning, Mac. You wanted to see me?”

“Jesus Christ, what did you do to Charlie?” Mackichan and Jordan were serious rivals on the slippery pole toward the top, and Mac always used the soft diminutive Charlie instead of the harder, more masculine ‘Chuck’ favored by Jordan, just to annoy him.

“Me sir? Nothing sir. I just did my job.”

“Well, you know where Mister Earl’s temporary office was?”

“Yes, I do.”

“You’re going to be in there with a kid from the drafting room, and you’re going to do the Corvette project by yourself.”

The “kid from the drafting room” was then 26-year-old Anatole “Tony” Lapine, later to become the chief designer at Porsche A.G. Cumberford had a photostat of the IBM-typed words “STUDIO X” blown up to sign size and posted it on an inner door, invisible from the hallway. It wasn’t an official studio, although the title remained in use at GM Design at least through the Ed Welburn period, more than six decades later.

Work continued on the C-2 Corvette, based on the 1955 Oldsmobile Golden Rocket Motorama dream car, with full-scale clay models executed in the Chevrolet Studio instead of in Jordan’s body studio. Design input came from Studio X, with direct model supervision by MacKichan.

Life in Studio X was a dream. Zora Arkus-Duntov, chief engineer for the Corvette, dropped by frequently to chat in Russian with Lapine. Both had Russian mothers and loved the language. One day when the two young X-men came into their workplace they found a D-Type Jaguar sitting in the middle of the space. Harley Earl was going to go racing. So the SS project was on, and it was unimaginable fun for two twenty-somethings. It was hard to believe that they were getting paid to play like this. The only fly in the ointment lay in the fact that only 700-some Corvettes had been made in the 1955 model year, and at least half of them remained unsold in Chevrolet dealerships around the country. There was serious discussion at higher levels of simply stopping the whole Corvette program.

What to do? Cumberford drove a Porsche 356 1500 Super, Lapine a Jaguar XK-120. Lapine was already engaged to the woman he would later marry, but Cumberford was dating… when he could find a young woman whose parents would allow their daughter to go out with a man in a two-seat car. So, the two began to plot a 2+2 Corvette as a solution to the pre-“pill” Fifties dating problem, and to the Corvette cancellation risk. Lapine did a 1:1 layout, establishing 108 inches as the shortest feasible wheelbase for such a car, and Cumberford engaged his old friend from high school days in Los Angeles, Stan Mott, who was also employed by GM Styling, to join in after-hours conversations about the idea.

Mott was primed for the project. After two and a half years of “decorating the whales” he was ready for a go-for-broke-project; to “design a valid car or get out” as he put it at the time. He was working in Body Studio 2, but had previously spent a year in the Oldsmobile Studio, where Earl’s base car for the next Corvette had come from. The three ‘conspirators’ then brought one Arthur B. “Barney” Clark into their secret little after-hours team. Clark was involved and interested because he wrote most of the advertising copy for Corvettes at the Campbell-Ewald advertising agency that had done all Chevrolet advertising for decades and didn’t want to lose that gig.

The first step was to send out letters asking a dozen influential people in the world of special cars — people like Briggs Cunningham of Le Mans racing fame, John R. Bond of Road & Track magazine and others of equal prominence — whether they thought a four-passenger sports car was viable. Every single person asked responded, and all were positive about the idea.

In the middle Fifties cowboy movies and TV series were extremely popular, so the clandestine team thought there ought to be a Western theme to the new car, and they came up with a list of model names that included many used later for a wide variety of products from all over the industry: Palomino, Scout, Pinto, Bronco, and of course the favored Mustang, both for the wild horses and the wonderful WW II fighter plane that had been designed and built by the General Motors North American Aviation division, using the GM Allison V-12 engine. A Corvette Mustang would be an ideal showroom companion to the two-seater.

Armed with all the documentation, Clark was asked to write an evocative description. He did, although had the young guys thought a bit about it, they might have tempered some of his thoughts, like “style it and forget it,” hardly a phrase to please Harley Earl. Nonetheless, on November 16, 1956 Cumberford sent that document to Earl, with a note saying he thought Earl would be interested.

Interested? What he was, was furious. The Engineering Policy Committee determined what GM would build, not some smart-ass kids (one of whom, Lapine was smart enough to quietly dissociate himself from the whole affair, leaving only Cumberford and Mott to account for their actions). Clark, working outside of GM’s direct employ, was ignored, as was the entire Mustang proposal. When, with Clark’s participation five or six years later, Ford started to work on what was the most successful new car of all time, GM had to scramble to come up with the Camaro more than a decade after the concept had been developed and presented (and totally rejected) within its own walls.

How did Lido Iacocca become “the Father of the Mustang?” Barney Clark went to work for Ford’s advertising agency, met a product planner named Don Frey, told him about “his” idea, showed Frey the paper Earl had refused to consider, and Frey in turn took the concept as his own idea to the head of the Ford Division of the Ford Motor Company, Iacocca, who in turn appropriated the idea as his creation.

Incidentally, the car Lapine got into production at Porsche, the 928, has almost exactly the mechanical layout the Studio X team and Zora Arkus-Duntov had worked out twenty years earlier for the Corvette, complete with rear-mounted gearbox. The Corvette did finally achieve that layout in production — thirty years after it was proposed in Studio X.

Meanwhile, what did Earl do with the egregiously offending Cumberford and Mott? Three days after presenting Barney Clark’s “Four-Seater Argument,” Earl ordered them to appear at his office. But only Mott was allowed in Earl’s inner sanctum, Cumberford having nixed his entry by signing his initials on the transmittal page of the “Four-Seater Argument”. Earl sternly lectured Mott that young fellas do not dictate company policy. However, after admitting that his two sons were “Just a couple of garden variety boys”, he said he admired Cumberford and Mott’s initiative and grudgingly gave them a second chance; they could have a project to design the 1961 Buick Special.

Their “studio” was a corner in Buick Studio. Buick styling chief Ned Nichols and his entourage of designers, board men, and clay modelers, considered them unclean for having defied the corporation’s hierarchy. Cumberford and Mott responded by blocking off their corner of the big room with full size mobile drawing boards. They went to work, initially on historical research. They found that each successive model of the Special since the Forties had been “longer, lower, wider” in advertising, with a single exception in the early Fifties when nothing was mentioned and the car was actually shorter, taller, and narrower for a single year. The “bad boys” attempted to collect blueprints of all the major B body changes since WWII, thereby having solid historical reference to help prove their much shorter and narrower (but lower still) 1961 Buick design was valid. They were told GM had no blueprint record of any body changes.

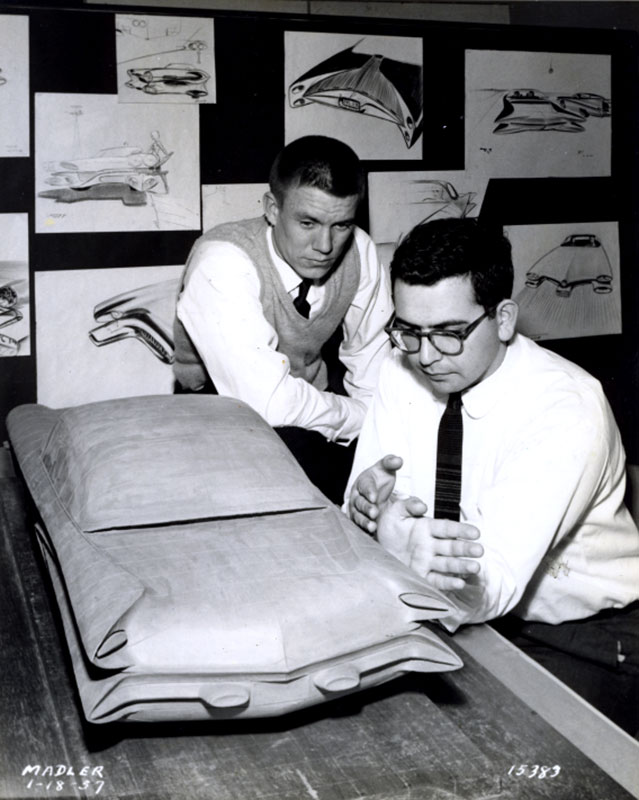

They produced stacks of design sketches, but after a month, they were expelled from their corner of Buick Studio into an even smaller corner of Body Studio 1. They settled on a final design that used the small aluminum V-8 Le Sabre/XP-300 engine with its supercharger removed, and had their pointed-fender shape reproduced as a quarter-scale clay model. To celebrate its completion they glued a notice on the Body Studio 1 lavatory wall mirror that “All employees must wash hands before returning to work.” The clay modelers really grumbled about it, but all washed their hands before returning to throw the brown goo around.

Meanwhile, upstairs, Earl was no longer amused. The mere idea of a smaller car outraged him, and the project was stopped because “we gave you a golden opportunity and you threw it back in our faces.” Cumberford and Mott were assigned to punitive tasks they refused, so on February 19,1957, Earl directed Bill Taylor, ex-FBI agent and top security man in the GM Styling Section, to terminate Cumberford’s and Mott’s employment, telling them that they’d never work in the industry again. Shortly thereafter, Mott and Cumberford created the world famous Cyclops II.

Eight years later the Ford Mustang was introduced at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Cumberford was on hand, taking time off from his successful Cumberford Design International company. He met and chatted with Henry Ford II, but refrained from telling Ford that his all new Mustang was conceived eight years previously in the General Motors Tech Center.

Mott showed up at the Fair, too—exhibiting the gokart that he spent three years driving around the world.

But all this is just between us, alright? Cumberford and Mott wouldn’t want to upset any one’s certainty about who invented the key car of the Sixties.

Copyright © Trebor Crunchog & T. Tom Meshingear 2017

Mott and Cumberford in GM Body Studio 1, back in January 18, 1957, with a quarter scale clay model of their 1961 Buick Special design proposal.

This is really funny.

Please remember that it is comedy with reality, personalities and facts stretched and warped for effect. For those who have not had the chance to have the experience to really understand this story I express that you should not make judgements on any of the characters including Mott and Cumberford. It is probably still the way that they see it. I am sure they were hired because they were individually talented, that is why designers were hired. I was told that the interview failure rate was 199 to 1. It was very hard to get hired, once you were in it was up to you to make the most of the opportunity within the confines of the culture. That creative culture was wide open but like any productive culture there were and had to be limitations and people whose responsibility was to enforce them. As dreamlike as it was it still had to produce.

There are many great stories about Styling, Harley Earl, etc. There was a culture of comedy in those days and people who were very skilled at the art of humor throughout the design building. Humor in the public sector was taking great strides via TV. At Styling, later to become Design, some of the funniest people were in the highest level of management, here as evidence I refer to the famous picture taken of Harley Earl’s staff where all were wearing propellors on their heads while at lunch.

Humor was characterized in different ways in different parts of the building, depending on who was in charge. Creativity is an essential part of humor and people who were relatively new in those days like Dave Holls and Stan Wilen were very funny, especially when together. Bill Mitchell was very funny. That encouraged others at lower levels right down to the sweepers to engage in all sorts of humor from jokes to trickery of all kinds. Because the work could be stressful, humor and a screechy radio were essential to moving design forward in any studio.

There are many merits in this piece but to characterize Chuck Jordan as a “politician” is wrong, he was a designers designer and that is a universally known fact. Chuck also appreciated humor greatly throughout his career and it was a daily component of his success as a designer.

Lapine would later drive a Porsche also, a black one and Bob Cumberford had his painted a warm bright yellow.

One of the most significant cars ever created by the Styling Section under Harley Earl is glossed over here, almost an afterthought although it was an exciting project and the work at hand. Bob Cumberford later wrote an article about it. I asked him who designed the Corvette SS and he said that “It was pretty much Harley Earl’s baby, that very little was added by anyone else”.

To get back to the Mustang story, it is hard for me to equate the Mustang with the Porsche 928. That is a stretch that if accepted would include many more sporty cars during those years even though the basic architectural elements are the same. People evolve basic concepts and many have jumped from one of the big three to another.

Those were the days of Corvettes and chicken coops.

DICK RUZZIN

Sadly, only readers of a certain age will recognize the tag-team of Crunchcog and Meshingear…perhaps they can reunite for a recounting of the valiant effort that Cyclops performed at LeMans?

Hmm…The Corvair was taking shape also around this time. So, there was a sporty car, four-passenger car close in size to the Mustang.

This is astonishing, and hands down the most interesting and well written article I have read about American automobile design in this era in a very long time. Congratulations to the author for an extraordinary and brilliant piece of research.

Thanks to Dick Ruzzin for his insightful commentary/wisdom regarding this posting. His professionalism is applauded!

John M. Mellberg

GM Designer, Ret’d.

I also recall that the Mustang was in response to the Chevrolet Corvair?

Dick Teague was not only one of the funniest designers, but also one of the funniest people I ever met. He had all sorts of very creative, hilarious names and phrases for people, things, and situations; For example, instead of saying somebody died, he would say, the person “shot through.” There are many others, but somehow the only ones I can remember right now are, well, a little off-color.

BRANDES,

Do not make the mistake of taking that article as factual and with wisdom, the result of research. There are many historic mistakes for effect as it is written as comedy and not as history. Research?

You must be kidding.

DICK RUZZIN

—My understanding is that this is not satire or comedy for effect, but a recollection of events as they happened recently written by Robert Cumberford and Stan Mott for Dean’s Garage.—Gary

I agree with Dick Ruzzin on his latest observations. Many historic mistakes and not completely with my recollections of the time.

—So, are you saying that they made it all up? Or it’s embellished history for the sake of a good story? What about the story is unsettling?—Gary

If Chuck Jordan was such a ‘designer’s designer’ (Ruzzin missed an apostrophe, and I added it for accuracy) and all-around great guy, I wonder how Chuck earned the title “Chrome Cobra?” I’d love to read what historical errors Dick Ruzzin found in this text, which wasn’t written as a joke. It all happened as stated.

But then, we can see that Ruzzin doesn’t read very carefully. No mention was made of Lapine’s 928 relating to the Mustang. It was strictly mentioned in connection with the proposed C2 Corvette we were working on in 1956, and the physical layout timeline is absolutely accurate.

Ruzzin took ethics lessons from the designer’s designer, I guess. When I was doing the Cumberford Martinique project with my brother in the early Eighties, we contracted with Rockwell’s Western Wheel Division to make our 415 mm TRX rims. I was somewhat dismayed to see that design show up on a cheap stamped tin wheel cover for the Pontiac Firebird, a product of Dick Ruzzin’s Pontiac studio at GM. He saw the design in the wheel factory in California, liked it, and took it as his own. I called him on it, but he shrugged it off, as he does our Mustang creation story. Or maybe he’ll want to suggest that we copied him?

I’ve always been very careful about attributing or claiming credit for design, as witness my writing that the Corvette was Harley Earl’s project, as Dick notes.

There exists solid documentation for this story, or we wouldn’t have put it out there, simple as that. I love the assurance of Ken Pickering that there are “many historical mistakes.” He was in no position to know much about anything at the time.

Just an aside; the Cyclops stories and illustrations were at the top of my reasons for reading Road & Track back then. Educational, too. I thought CinZano was an Italian motor oil until I saw a bottle at a liquor store while presenting my fake I.D.

DICK RUZZIN

The record shows that I never worked in either of the Pontiac studios at any time during my 39+ years at GM. I also never worked on a wheel for Pontiac. I also never heard of a designer wasting his time by going to a wheel factory.

Bob. I think this proves that as good intentioned as you are your memory of what happened in those days leaves much to be desired. I met and had communication with you on the Wednesday before Thanksgiving about 5:30PM at the Detroit/Windsor Tunnel in 1958 and later at the Frankfurt Auto Show between 1995 and 1997. No discussion about Pontiac wheels between us then, we talked two times after that. At the Tunnel you asked me if I could stripe your Porsche that had just been painted, yellow. You had it there and showed it to me..

You believe what you wrote, It is history as you remember it. Others at Styling(Then), saw it very differently and that was still remembered and discussed when I hired in.

You are in denial about the reality as remembered by many others.

DICK RUZZIN

Funny thing: I was never in Detroit in 1958. And my Porsche, painted yellow in 1956, was black by then. Guess there are other divergent memories. And i must be wrong about your connection with Pontiac, if you say so. I wasn’t inside GM after February ’57, and you were. Lucky me. And I wouldn’t count too much on the accuracy of the memories of those left inside GM after we were gone and before you hired in. They had to tow the party line. Guess that proves that we made all this up, huh?

Who really invented the Edsel? Success has a thousand mothers, failure an orphan. The idea of the Mustang was a natural progression exemplified by the XK120 fhc two seater followed by XK140 with small back seats. I’ll bet plenty of folks in Detroit had the idea. A no-brainer. The magic of the Mustang was the use of a cheap chassis, and its modern styling, and sporty fastback and convertible derivatives.

Interesting story line, not so far fetched. Richard Truett is right on target in regards to a sporty car from GM being prior to the Mustang. I was there, in Dearborn, Michigan at a place known as Ford Styling from 1961 through 1964 and in the very thick of it. So so thick, that management of all persuasions would never let you forget the fiasco known as the Edsel. It was a constant inculcation.

Furthermore, that rear engine sporty GM car the Corvair having a108″ wheel base sold over 300,000 in 1961. And guess what, this made Ford management more nervous and culpable due to the fact that the 109.5″ wheel base Falcon was projected to loose 50% in sales in coming years.

These consequences promulgated the Joe Oros Weekly Mantra of “the car has to look Italian.” I am sure that was due to a directive by Henry Ford who wanted to buy Ferrari. My design contributions began in the latter part of 1961 into 1962 including both the Mustang 1 and the 64 1/2.

Not bearing the name of Mustang this became the first iteration to be really accepted by the administrative players and Henry for the nameless new car. In 1962 the 64 -1/2 would come out of the Pre-Production Thunderbird Studio under Joe Oros. The Mustang 1 would come out of Advanced Styling Studio headed by Bob Maquire.

The story gets more complex. Let us look at the 63-1/2 Falcon Sprint. I was now working with Uwe Bahnsen in the Ford Interiors Studio on the interior design of this vehicle. With the bucket seats and console, the vehicle would begin to replicate the 108″ GM Corvair wonder car, but the Falcon wheelbase remained at 109.5″.

With the inclusion of the 260 V8 engine and 4 speed transmission would now place this 32mpg six cylinder into a totally different class.

Unfortunately, the Sprint would only sell 15,000 units. So, the Falcon with a new skin became the answer. And Guess what? The new skinned Falcon now known as Mustang would take on the 108″ wheel base of its competitor. Is that not the ultimate form of flattery?

Throughout my career as an art director and designer I have had my ‘rejected’ designs presented as work of others above (and below) me on the corporate food chain, as proposals, in portfolio, and resumé. Nothing exists in a vacuum and corporate advancement is by any means possible, including claiming creation of the work of others and claiming ignorance to existence of earlier work. Pontiac in the early 1960s had the Lemans with a V8 in front, a transaxle, and a rigid tube containing driveshaft (that ‘rope’ thing) tying the whole thing together as a unit – same layout as Porsche 928, save for the ‘rope’. Would be foolish to declare the ‘rejected’ Chevrolet Corvette transaxle layout was never seen or discussed by anyone at Pontiac, also to declare a designer would be ‘wasting his time’ visiting a wheel factory.

Cyclops – some of DO remember the Crunchog & Meshingear!

Discussions of the Falcon Sprint and Mustang must also consider Ford’s awareness of, and participation in both Carrol Shelby’s high performance Cobra and Jack Griffith’s even faster sports car, the 289 powered Griffith 200. It is claimed that Griffith built the first high performance V8 Falcon at his Ford dealership on Long Island before creating the Cobra defeating eponymous 200.

I love the banter. As an X street racer my stories, both wins and defeats are fuzzy and lopsided. The insight into the politics in this hidden world, for most car guys is exciting. Maybe a joint publication with banter included about the collective memories of these politics would be great?

BOB,

So it could not have been ’56 as in ’56 I had just bought my TD. It was painted Corvette Blue and striped in ’57 when you saw it. You have your dates mixed up. Actually the exact date is meaningless, the meeting did happen.

I think the Ford story about the Mustang is a more logical explanation of it’s creation, where was Lee Iacoca?

DICK RUZZIN

A fun read, you guys keep having fun. Life is short.

That photo with those two guys and their “art” on the wall, and the clay model on the table is pretty telling. The artwork and the model easily qualify as totally HIDEOUS, not a strong argument for the truth of their egotistical hit-piece article.

Frankly, knowing Dick Ruzzin for decades, I would go with HIS interpretation of events, without hesitation. Also, knowing and working for/with Jordan over many DECADES, Dick’s opinion strikes much more true.

Cumberford and Mott, legends in their own minds.

To Allan Flowers,

Thanks for the laugh. Happens every time we shake the ol’ corporate cage.

Now, I don’t want to ruin your morning, but my experience with Chuck Jordan was quite different than Robert’s; Chuck was in charge of the Euclid Studio in Plant 8 (Siberia) in summer ’54. I was assigned there for a few weeks before being transferred to the Oldsmobile Studio. Earl rarely visited Plant 8. We had the radio blaring pop music and a pot boiling coffee all day. Chuck brought in the latest Playboy magazine for all to peruse. It was a most agreeable environment.

Regarding our sketches and clay model of our ‘61 Buick Special proposal, I know they didn’t possess the delicate grace and esthetic beauty of, say, a 1958 Buick Roadmaster 75, or a 1959 Chevrolet Bel Air. For my part, I presume it was due to my preference for machinery like Cyclops, Pignatellis and the Christie-Cunningham LeMans Sportank.

That explains it.

DICK RUZZIN

Whew! I was worried that you wouldn’t understand.

As one of the stylists on the 1965 (’64 1/2) Ford Mustang I want to thank Gary for getting all this published.

Both interesting and hilarious, the story, and following letters, held my attention and gave me some great laughs. I loved it and will check back to see if there are any more emails of people peeing still over the fence at each other.

I don’t dispute the idea where the “Mustang” idea really began, but it is important that Ford got it into the market.

Jerry Malinowski’s comments were all right on target. (He and I went attended the Cleveland Institute of Art together and both were at Ford at the same time.)

Thanks to all for making my day!

Phil Payne

To Bob Cumberford: Is it correct that you were part of Ford logo in the reflecting pool caper at the Tech Center? As late as the 1980s Chuck Jordan did still not see that as a humorous occurrence.

I can’t tell fact from fiction here, but it makes a damn entertaining read either way!

Jerry Malinowski

Phil, Dick, Brake Servo, Bob, Stan,

What a great forum. I clearly remember the iconic Cyclops featured in Road and Track magazine. A job well done by Stan and Bob.

As for Lee Iaccoca, he was head of Product Planning and had a background in engineering. He also excelled in sales and promotion. His Product Planning group came up with the idea of using the Falcon platform for the Mustang. To my knowledge he had nothing to do with the physical design of the Mustang.

In 2013 one of the founders of the Saratoga Auto Museum contacted me for consultation of the history of the Mustang and the curating of cars. This was pertaining to the upcoming 50th Anniversary Exhibition the museum was developing for 2014. At the opening of the exhibit I was a special guest along with Edsel Ford, Lee Holman and Mary Seelhorst.

We had many interesting discussions relative to the history of the Mustang and Falcon progenitor. One particular story of interest told by Lee Holman of Holman and Moody revealed some interesting historical development of the 1963 1/2 Falcon Sprint. Lee related that Holman and Moody were under contract with Ford Motor Co. to modify a 1962 Falcon by transplanting a 260 V8 into the 6 cylinder engine bay and replacing the 3 speed column shift with a 4 speed on the floor. Lee further stated that this test mule was his daily driver to high school in 1962. This was the trouble shooting test method back than which exposed engine over heating in the initial stages of testing.

In 1960 Holman and Moody as well as Edelbrock and Bill Strope made a three carburetor set up for the 1960 Falcon’s anemic 144 c.i. six cylinder. The Holman and Moody kit included a head, cam, lifters, etc. I owned a 1960 Falcon as my Detroit winter salt sled to keep the salt worms from eating my TR 2. There was an inherent problem with the early sixes with supplying oil to the valve train and the lower end tended to be weak especially when equipped with speed kits. This was confirmed by my ownership and guys who had the three carburetor set up. The answer was the V8.

Phil it was great to hear from you.

I would like to contact Phil Payne we worked at Ford in the 60s and attended the Cleveland Institute of Art

Gary,

Reading this article later is really a hoot. Congratulation to Bob and Stan for creating this memorable catalyst.

The Mustang as a personal car was a huge success no matter how it happened and it continues today. The Corvair was already out there big time and as soon as GM found out about the Mustang the Corvair Monza was created.

As GMs strategic plans developed in Ed Coles mind there was no room for a future rear engine car that was being picked on.

I saw the Monza mocked up on a red metallic base two door at Fisher Body when I hired in there in fall of 1959.

Gary,

Just saw the nice selection of Ford Styling Mustang stuff, and then read your re-issue of our tale of where the Ponycar idea originated. And I see that I owe Dick Ruzzin an abject public apology. My problem as an 80-something geezer remembering things that happened to a boy who left GM at 21 is that I find it pretty hard to distinguish one GM Lifer who persisted through the years from another. Ruzzin wasn’t the bad guy who knocked off Martinique wheel for a Firebird wheel disc in 1980. (How can a guy be bad who drives a Mangusta?). It was one John Schinella (spelling?) who was the Pontiac guy with Chuck Jordan ethics. So any untoward comments about Ruzzin’s ethics were misplaced, and I’m deeply sorry.

Of course I stand by the tale of how we invented the sporty four-seat compact concept, which the Corvair wasn’t. The Oros Mustang was a wonderful design, it’s front end graphic composition very like the earlier Dual Ghias. the fender profile like the ’61 Lincoln, one of the best designs Ford ever got into production. Now they just do motorized filing cabinets. So it goes.

Jerry, Phil, Eric,

Any way you look at it – what a story. I was one of the 5 designers assigned to the

Thunderbird Pre Production Studio in 1962 where the original full size concept model, of the Mustang, (code name Cougar) was done under the direction of Joe Oros. So far I haven’t heard any mention of those contributing designers. They were Martin Kalman, Frank Ruff, George Schumaker, Charlie Phanuff ( Studio Manager), and me. We papered the walls with tons of great sketches but most of the real designing was done by Joe. Among a couple of other things I got to do the animal and collar inside the grille opening ( a cougar at the time- later to become the mustang) going in the wrong direction.

I had somehow missed seeing this until now. The article is fun, the comments section even better!

Both of those things are relevant to an article I read recently at Hemmings regarding the design of the 1968 Dodge Charger. Link:

https://www.hemmings.com/blog/2019/05/08/richard-siass-1968-dodge-charger-design-both-defined-and-ended-his-career-at-chrysler/

There are a number of similar themes in regard to who did what, who received the credit, and the fallout in terms of personal feelings that results. Seems to be a quite common situation in design studios and a risk faced by many designers.

The Hemmings piece has some interesting comments too, including some from Leon Dixon, Alan Berry (ex-Chrysler designer) and Burt Bouwkamp (Dodge Chief Engineer and Product Planning Manager during this time), who tries to offer some perspective on Bill Brownlie’s role in the development.