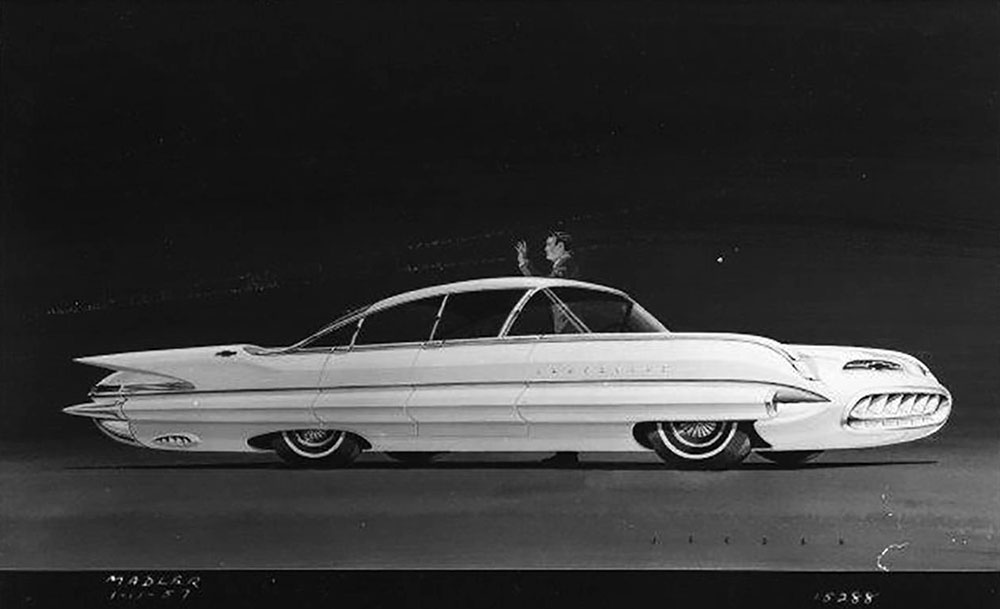

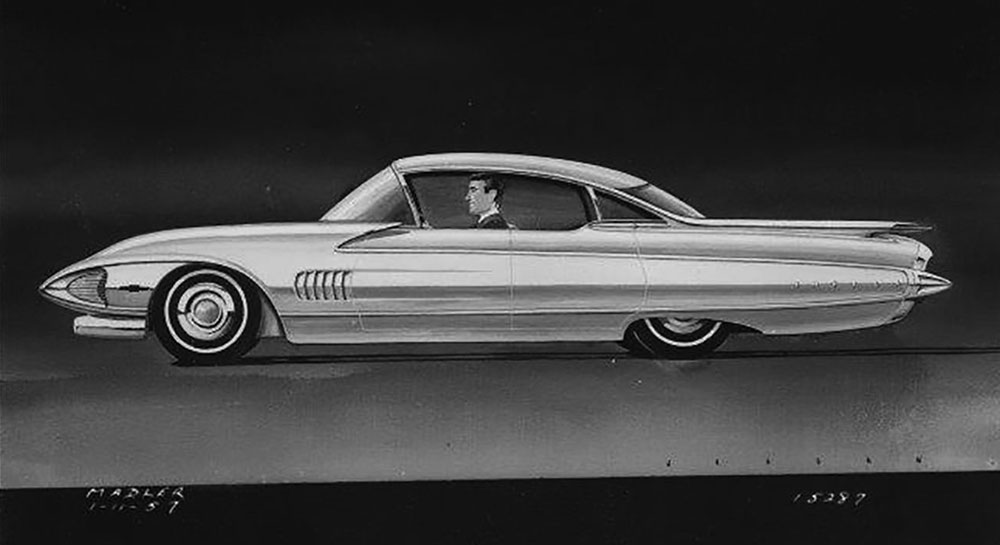

I had never seen these development images of the ’59 Chevy before. These hideous designs must have come about by conflicting and contradictory direction or lack of same. At a time where ’50s American automobile design had run its course and had to make a transition into something that made more sense, maybe Earl just couldn’t change directions. I don’t know. Pretty scary stuff. The production ’59 Chevrolets were tame and refined next to these earlier proposals.—Dean’s Garage

How GM‘s Radical 1959 Chevrolet Came to Be

by James Humble

Source: Hot Rod Deluxe, May 21, 2015

Even as the epochal and precedent-breaking ‘55 Chevy line was causing sensations at the dealers’ showrooms and racetracks, GM management had already decreed the first step in a market strategy to up size and upgrade all its products. Well, let’s face it: in the ‘50s the automotive marque to which the overwhelming majority of the automotive masses aspired was the General’s flagship: Cadillac. Traditional rival Packard was going into its final coma, Lincoln was only a spunky wannabe, and Chrysler’s Imperial was a distant “me too.” The Caddie, in the eyes of the public, held the whip hand in terms of luxury, speed, and “charisma”—a quality that is hard to define, but sells cars. The tail wagged the dog and the “Low-Priced Three” were dog itself.

These were the days when new-car introduction time was like a circus in town. When its arch competitor Ford and upstart Plymouth both came out with all-new bodies and frames in 1957, ever wonder why big Chevrolet didn’t follow suit? It’s too easy to assume that as king of the Low-Priced Three market, Chevy merely wanted to prolong the line of that classic with the iconic 1957; nope—the front office had decreed that Chevrolet would spring a big (literally) surprise on the market to claim lasting precedence in 1958! Ford’s all-new—if traditional—body thus sold very well, and controversy exists to this day who won the 1957 sales race; suffice it to say that Chevrolet not only didn’t like to lose, they likewise didn’t relish a close finish. This surprise was a new line-leader called the Impala, and it would bring even more Caddie cachet to the arena. It was to be a package: a completely new, compact V-8 at 348 CID (available with dealer-installed Borg-Warner four-speed), a new X-frame that moved the engine’s harmonic balancer up even with the spindle centerline—all in support of a more luxury-oriented, and appreciable heavier, body. Released only as a convertible and two-door hardtop—remember that the 1958 Bel Air series had its own hardtop that shared few body panels—it overwhelmed the warmed-over second-year styling of both Ford and Plymouth, and notched up the luxury target for years. And, in a hotly contested race for high sales, it regained the winner’s circle—but the challenge would be how to follow that act?

Precedent was broken a year later when GM planners preempted the new bodies (and similar Pontiacs as well) with a radically new design that retained only the basic frame and power packages of the 1958s. Why? Well, part of the plan was to get all the divisions in sync over at Fisher Body with intensified inter-line rationalization: think roof and window shapes. After that, C-B-O-P-C could march forward in a unified rank, thus significantly simplifying parts inventories and saving the bean counters lots of legumes. At least that was the theory. To keep these developments in context, recall that a wild and hyper-controversial new lineup was being readied by FoMoCo in 1958—that styling boomerang called the Edsel! Sensation proved its worth, and the E-Car sold very well at first, but mostly to the detriment of Ford and Mercury. Few now recall the poor timing of it all; 1958 was the year of the “Eisenhower Recession” and though the new Chevy again prevailed in its market, overall car sales slumped badly, and adventurous marketing proved hard sledding!

For 1959, GM Design Center would set the “look” and basic body parameters for a number of wheelbases, and engineering could fix all the crucial body dimensions—firewall and door hinge lines, floor and roof height, and so on—and the five division studios could take it from there. Looking back on the photo files of GM Photographic a marvelous nuthouse of ideas can be revealed, with lots of themes and treatments recognized that later crossed marque lines. Of course, the individual divisions had always expected to adapt to some degree of rationalization and corporate identity, but in those dear, dead days, in-house politics and sales competition being what they are, each nameplate still fought the trend like the Army fights the Navy fights the Air Force!

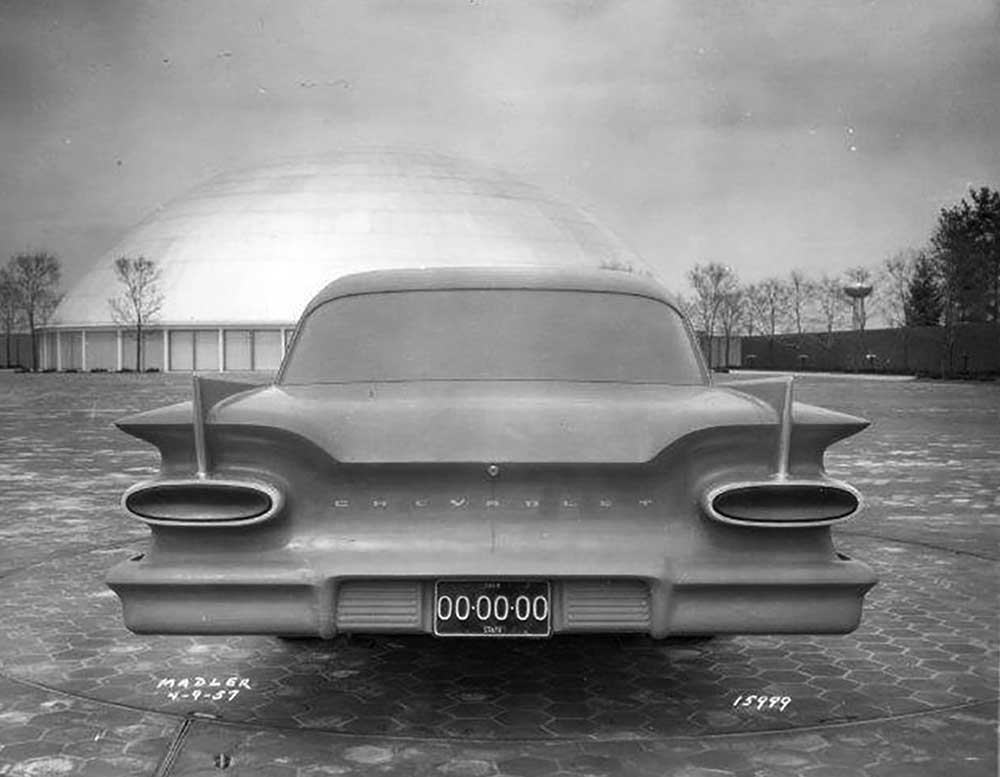

With full management approval, Chevrolet stylists took a huge gamble that those huge horizontal fins, even in a tail fin crazy market, would catch the fancy of the new-car buyer. Wide “cat’s-eye” taillights never prototyped on any GM dream car drove home the impression. Controversy didn’t hurt, in the real-time market, as all sorts of rumors surfaced about the 1959 cars becoming airborne (or at least unloading the rear springs) in high-wind areas: supposedly a coastal highway tunnel had the capability to cause the lifting of the rear suspension to a really thrilling extent. Aerodynamicists scoffed, noting that the airfoil curve that causes lift was totally lacking, but it became an urban legend. As the dropped-in-front “Dagoed” look was beginning to move from street rods to late-models, the sight of radically raked 1959s might have nurtured this rumor.

Frontal styling for the new lineup was a bit controversial for a different reason: critically viewed, it didn’t quite “match” the rear look as seen in all previous Chevys. Though pleasing in a less radical way, to some critics it looked as if it had been chosen “off the rack” by the stylists and merely attached to the distinctive tail by the expedient of slathering clay to join two design bucks. Some definite Cad influence can be discerned in the stamped-aluminum grille texture; a toothy ‘Vette-inspired unit was considered! The upside was that the treatment lent itself to loads of effective restyling, which customizers, even the high school auto shop kind, loved. The most popular of these was the replacement of the designers’ nice “grin” with a simple tube grille of chromed bars. As to the twin pseudo-air scoops at the hood parting line, one custom shop artist (I think it was Darryl Starbird) remarked, in noting how little he cared for to the effect, that it looked like one of the body designers had stood too close when holding a running grinder, and having buzzed off the leading edge, had to repeat on the other side for the sake of symmetry!

The 1959 coupe roof was pretty and complemented the look perfectly; it still looks sweet, if you grant that the rear seat occupants might get a bit warm. Thought the “Forward Look” Chrysler products had sported a modest bubbletop look as early as 1957, but GM stylists trumped it with a super-thin C-pillar and beach towel–sized roof panel on all their two-door hardtops, ending it with the low-production and even prettier Bel Air Sports Coupe in 1962. Even the two-door sedan roofs looked rakish. All divisions had an optional four-door hardtop profile that was convenient, but rather bland. While the fin design was no particular help at the new Daytona oval, the roof profile was a real plus; unfortunately, Pontiac and Olds had it too. With a well-worn ’59 Sports Coupe “Junior” Johnson did win the 1960 Daytona 500, but it had been discovered that the “W” head/combustion chamber design became a bit breathless on the high-speed oval. Fortunately, it proved to be a torquer that always did better on short tracks or drags.

Performance-wise, neither year had it all their way in the Stock Car wars; there was plenty of competition, especially from GM rival Pontiac with a larger-displacement 398 CID motor that breathed very well and rode in a perimeter frame with a wider stance. The second-gen four-seat Thunderbird was low, had a smaller frontal area, and was equipped with the big Lincoln 430 CID powerplant. However, at the now burgeoning dragstrips, the Chevrolets did very well, and seemed to be everywhere garnering NHRA class records, both with the 348 and the 283 CID in lower echelons. That the cars were campaigned hard and in great numbers is told by a perusal of the strip box scores from your old National Dragster weekly. Bear in mind that despite the fact that the “W” was actually a tad lower than the small-block, it was more massive and couldn’t really be shoehorned into the elderly frame of GM Managements’ performance car of choice, the sporty Corvette.

From its introduction, the W benefitted strongly, as did many GM cars, of the availability of the Borg-Warner T10 four-speed (originally developed from their heavy-duty three-speeder), especially in the upper stock/stick classes at the local strip. Quick: what carburetion equipment (not counting FI) was never offered on the “W-motor”? That the engine was never sold with a basic two-barrel carburetor bolsters the stance propounded in the prestigious Society of Automotive Engineers “Engineering Journal” of 1957 that Chevy boffins were on the hunt for more BHP and torque with the 348 series! Not many V-8s can make that claim; the “W” came only with the basic Rochester 4GC four-barrel, or optional triple Rochester 2GC two-barrel intakes. Later, of course, the 3X2s were supplanted by two hard-to-quench Carter AFB four-barrels, but that was with the rather tardy advent of the famed 409ci iteration. Why did the “W” get the appellation of “truck motor”? Like the original 265 CID mouse-motor, it was introduced in both automobiles and commercials simultaneously; but the 409 was retained in Chevy’s larger gas-powered trucks after it had been supplanted by the 396-427ci big-block in passenger cars. Chevrolet engineers stated in the SAE Journal that based on the metallurgy available in 1955-56, they didn’t think the small-block could be reliably built beyond 301 CID. But recall that the competition’s little V-8 never went beyond 312 CID.

Whereas division rival Pontiac held its own against the rapidly developing threat of the B-block 413 CID Chrysler products vary, especially with automatic-equipped cars becoming heavy threats for top stocker after the advent of the Torqueflite, Chevy had really needed the 409 at least a year earlier. And the ancient two-speed Powerglide, never a threat in stock configuration, had to soldier on in the automatic classes for too long. The 1959–60 Chevrolet, especially the Impala Sports Coupe, was the ideal car to cruise main and attract attention; under the streetlights, it screamed (especially in Gypsy Red lacquer, strong forward rake, and playing a tune on dual Pacemaker mufflers and the three-twos intake) “Hey—look at me!” With all the windows rolled down, of course, cat’s-eyes glowing to the rear, and AM radio thumping out a monaural “Little Darlin’” or Jorgen Ingmans’ “Apache,” one was automatically trolling for black and whites!

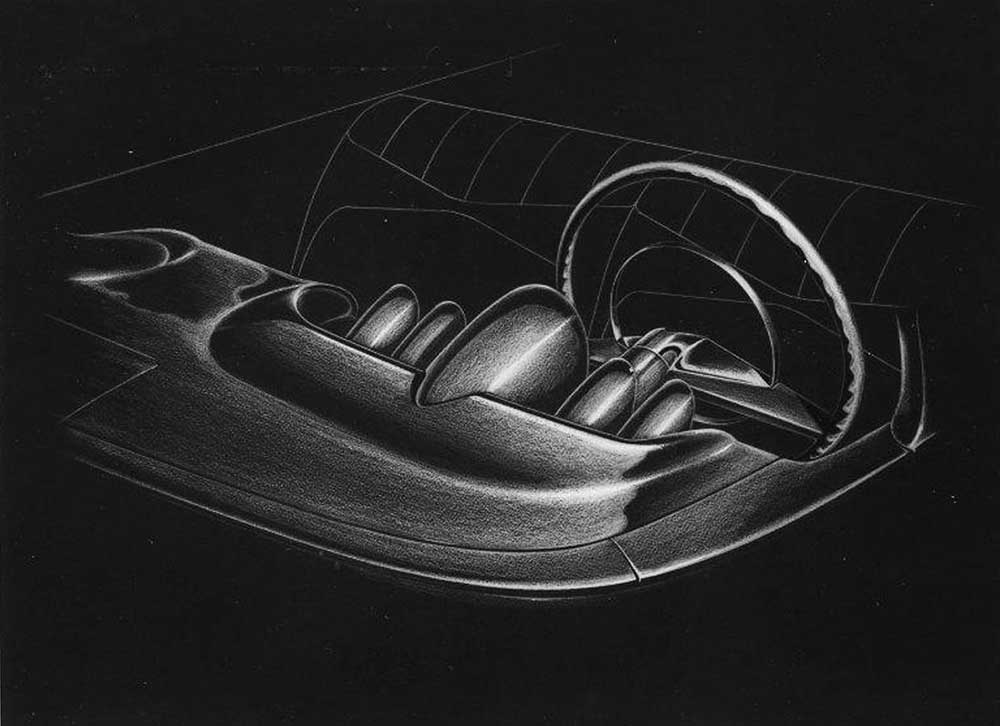

The new body essentially lasted two years; in 1960 the boys in the styling backroom had toned down the flamboyant fins a bit, making the decklid a bit flatter, and reinstated the modest round taillights that had arrived two years earlier, and these soon became a brand identifier even on Corvette and Corvair. Also, they decreed a pleasing new, less radical grille shape that was tied quite neatly into the rear treatment with a high horizontal reveal line. Otherwise, the 1960 lineup was almost identical to the 1959 in most respects, and despite the pretty new Ford styling, featuring gullwing horizontal fins and bubble-roof, interestingly it took the sales trophy. Before summing up, we should add that the Motorama-inspired dash/instrument treatment (besides the inclusion of “idiot lights”) was a grand slam of a design!

The wild-styling card was discarded by 1961. That marked the advent of non-controversial body styling—starting a generation of Chevrolet domination in sales of what had become known as full sized family cars. And a half-year intro of the balladized 409 (and rare Z-11 427) the 348 W was progressively supplanted by the legendary 327 CID SBC, and the awesome Rat motor—produced partially on the same assembly lines as the W—was just around the corner. Well, heck: even the Caddies had become conservative and trimmed of fin by then. But now, as then, the 1959 Chevy turns heads as a street cruiser on Saturday nights!

I would love to see some 59 Buick clays or sketches, please do a future article on this car! The 010 early clay front shot, I see the drivers’ side headlights canted, looks like that may have been the start of the 59 Buick front, maybe borrowed from one studio to the other.

-John

Interesting story but there are a few more facts that should be recounted. Most of the stories about the crazy days leading up to the ’59 designs have been told on Facebook pages and other media but maybe the best description is in David Temple’s new book, “The Cars of Harley Earl”. In Chapter 12, David reviews “Styling the 1959’s”. It was an interesting time. For several weeks, I worked in the studio where we were trying to meet Earl’s instructions to do the 1959 Buick with a LeSabre front end design. It was not a pretty sight! David Temple. in Chapter 12, has a section “A revolution within GM Design” that captures the moment.

Ken Pickering

As I have understood it, the ’58s & ’59s were a reaction to losing the styling lead to Virgil Exner’s Forward Look by Earl. This story is well documented. The Jukebox ’58 Olds & Buicks are not seen as his best design moments.

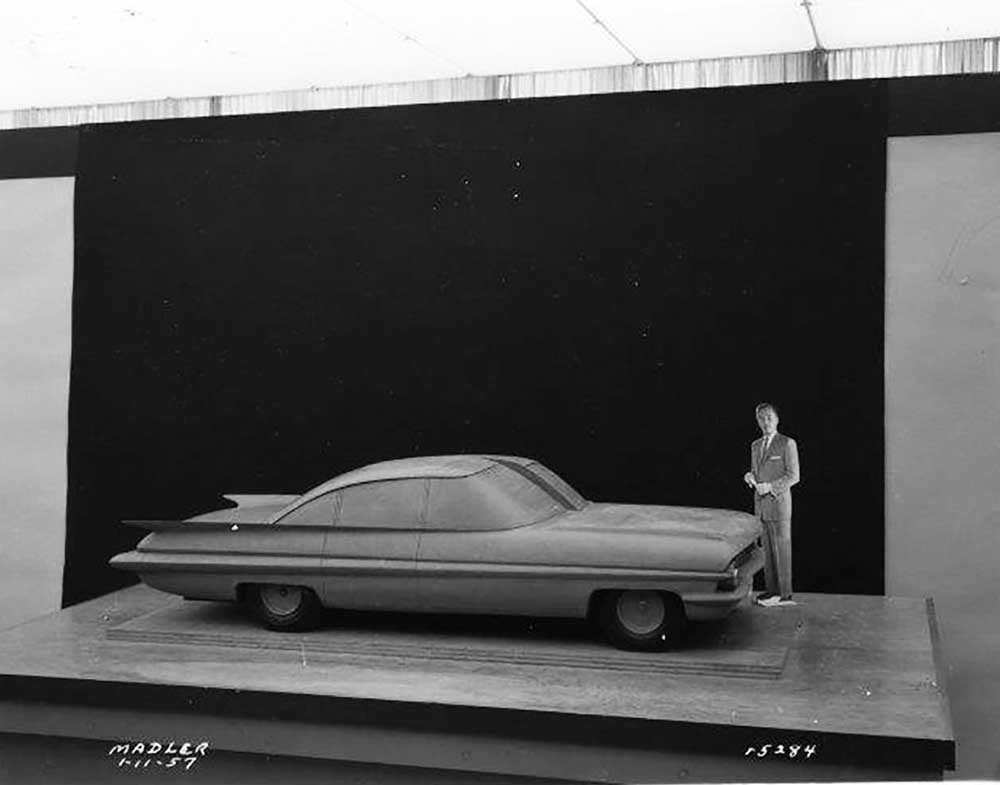

The 1959 cars turned out to be well done and refined compared to the early models seen here. That is Claire MacKichan, in the scale model cut-out, he was the head of the Chevrolet Studio when those 1953 through 1963 cars were done. Stories like this that are based on hearsay by people who were never involved in a design or engineering program always tend to turn out to be comedy routines. Writers, not to denigrate them, take a fact from here or there and knit them together with their own assumptions based on more here-say and more divergent assumptions. Their skill is writing but they cannot resist entering the scene to help you understand the subject. Whichever way they think it should be done.

By the way there were Impala two and four door sedans as well as a wagon. The most amazing thing to me was the very clever evolution of the 1959 cars and the sharing of glass, hinges, door inners and other body and chassis parts that were completely and effectively disguised by the dramatic designs. That was the point. Bur who would say that the 1959 Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Buick and Cadillacs were not good looking? The Chevrolet, in context with the times, the Fords and Chryslers were dramatic and very reasonably priced.

A silver blue Chevrolet hardtop or convertible was a stunner in those days. You cannot judge them by running them through a today filter. At the time it was the dream as visualized by the earlier Motorman cars and even more, you could buy them at a competitive price, you could own one.

DICK RUZZIN

Gary,

If these look bad how about those 1956, 57 and 58 Corvette models? I think you have seen those. Again, cooler more skillful heads prevailed, Bill Mitchell?

Dick Ruzzin

Having been on the staff of “Collectible Automobile” magazine, I had the rare opportunity to see many of these photos of GM styling clays of the day. The wild ideas for what stylists envisioned the buying public wanted at the time was nothing short of amazing. Quad headlamps had hit the market in full force by `58, but how to apply them to design seemed to be open to debate in the styling studios. Clays for the `59 Buicks showed just how are those ideas went in clay. The new `59 B & C-body GM cars were to be based on the Buick underpinnings, with individual sheetmetal done by each division. And GM probably pulled it off better than Ford & Chrysler by far. One has to remember what started GM’s vast departure from the 1958 designs to begin with. It was GM execs seeing Chryslers new designs for their `57 models during the late summer of 1956. Knowing they would delightfully shock the automotive buying public, it set in motion GM’s mad scramble to one-up Chrysler with their own new designs. And GM managed to do it only two model years after Virgil Exner’s hot new ‘forward look’ hit showrooms. Quite a feat, given the day.

What was going on with Pininfarina? They built the shortened XP75 Buick coupe that featured both 1959 and 1960 styling in 1957-8. Could there have been a huge input by Pininfarina in the styling of the 1959 cars that was never made public? Remember Earle and Pininfarina were good friends.

To Bentley T,

The Buick you speak of, was it a two passenger, silver, maybe two of them?

I saw one parked in front of the Northland Playhouse in summer of 1960.

I wonder what happened to those cars?

Regarding the timing of the car, the production 1959 Buick would have been done in two years, the design started in 1957 and finished in 1958. The program leveraging five divisions including platform deviations was very complex so influence by anyone outside would have been minimal. It is hard to influence anything that large and complex with that much momentum from Italy with minimal influences. The influence probably went the other way.

Dick Ruzzin

To Dick Ruzzin, The two 1957-8 XP75s were the big mystery. How and when did Pininfarina know what the 1959 and 1960 Buicks were going to look like? Was it their design suggestion? Was it their idea for the 1959 Buick cars? Was it a concept they were trying to sell GM? or were the two XP75s a job order from GM.

But remember while all this was happening, Pininfarina got the job to assemble the 1959 and 1960 Eldorado Broughams with apparently most exterior panels coming from GM.

I was at Ford in those years and, uniquely, Ford obtained the blueprint for the ’59 Chevy and in a secret room, not open to most, created, in clay a full-size ’59 Chevy. Sounds like a “B” movie, but it happened.

I did get to see it, and it looked authentic enough to believe it came from GM. Personally, I thought it was so extreme (absurd) that it wasn’t the final product, but an interim one; Ford did their fair share of nutty stuff, that got toned down (not always) before production.

I had heard, and believe, that GM, taken by surprise by Chrysler’s ’57 fins, wanted (and got) radical designs for ’59, with the restriction, except for Cadillac, could not have fins rising above the horizontal. GM designers, restricted by that ruling created the illusion of fins, by giving the rear body a downward thrust, in conjuntion with the horizontal ones.

Dick Ruzzin – Always glad to hear from you and I enjoy your comments. Regarding “the writers”, I believe David Temple has captured this history very well. I was there and involved in the process and have related my memories to David to add what he had already collected in the way of facts. These were difficult days for GM and the story about Chuck Jordan seeing the 1957 Chrysler cars on Mound Road is true. So is the story when I rented a 1957 Plymouth and had it placed in the patio for Earl to see. And, after walking around the car, I remember well his comment, “I wouldn’t piss on it” as he walked back into the building. Yes, the final 1959 GM models came out great but only because Mitchell, Curtice and the Studio Chief Designers made it happen.

Ken Pickering

According to early notes, meetings and inter-office planning memos from Ford’s sanctimonious “E-Car” division, GM’s (and particularly Chevrolet’s) most feared influence was the Edsel. This is well-documented throughout the 1956-1957 gestation of the Edsel’s design, as well as by David Jenkins, Edsel’s lead marketing mover and shaker at Foote, Cone & Belding.

“When people look at cars in traffic, they most often see the rear first,” Jenkins recalled, “and a first impression is typically the strongest.”

Edsel’s forthcoming flat, finless quarters and huge horizontal tail lights had everyone at GM and Chrysler shivering in their boots, lest they come out with a 1958 car that’s already two years old. (See photos here.) Chrysler was still bobbing in the red ink Jacuzzi from recent quality misadventures and Studebaker and Rambler weren’t even on the horizon. Only GM had enough spare change to do some 11th hour back-pedaling and get an Edsel-like product to market by 1959, and Chevrolet won the honors.

It’s been commonly stated that no one liked the Edsel. No one, that is, except the car designers in Detroit.

To correct a glaring miss-statement (above), “the E-Car sold very well at first, but mostly to the detriment of Ford and Mercury.” The Edsel was in fact, dead in the water the day after it arrived in showrooms. To quote Dave, “It took off like a rocket that hit a brick wall and fell into a pile.” And while 1958 was one of the worst overall sales years in Ford history, the sales of Fords and Thunderbirds alone would have saved the company by a wide margin, even if Lincoln, Mercury and Edsel hadn’t sold a single unit.

The Buick XP-75 was not designed by Pininfarina, but was designed by GM Design; the two cars were simply built by PF. There is a sidebar on those two cars in my book, “The Cars of Harley Earl.” One of the cars was built for Fisher Body president, J.E. Goodman. That car was eventually scrapped; the fate of the other remains unknown.

Interesting comments in the story about “all the crucial body dimensions—firewall and door hinge lines, floor and roof height, and so on” was shared on the ’59 bodies to save costs by sharing components. That had been accomplished earlier at Chrysler with the 1957 models. Any “front clip” sheet metal could be shared from one product line to another, yet each of the 5 divisions had a distinctive style. The article completely avoids the reaction of GM to the Exner styled “Forward Look” cars from Chrysler.

Thanks David, now we finally know.

I’m surprised to see sketches from Chuck Jordan above for a possible 59 Chevrolet, I thought he was in Cadillac around this time frame? Was he allowed to work in multiple studios?

David, I’ll have to pick up your new book, the XP-75’s seem to be the least mentioned two concepts ever. Besides an old Collectible Automobile article, you just never hear much about these cars.

I would love to hear more comments on the 59 Buick, good or bad, from the designers on here. Would some of you agree it was one of the first times the same theme was used for the front and rear? It seems like that to me, the front wings match the rear wings somewhat, not many cars of the era (if any) had this effect going on. I still think it’s very unique, how it comes together and works on that car.

Robert Cadaret ,assistant Chief Designer at the time the 59 Chevys were done I believe related that Harley Earl would come in and review the winged rear end and make a suggestion. Later separately Ed Cole,head of Chevrolet would come in and review the rear design and push the design to more extreme. Hence the final result. Also there is an excellent film done on the 59 Chevy by Gm at that time showing its design development. It features head of Chevy design Clare MacKichan. It is on you tube.

Just look at the recent history of Pininfarina in relation to the Buick and you will see that in no way were they responsible for the design. Same for GM in the reverse.

If that Buick were to be found today it would far exceed the auctioned Oldsmobile F-88 price by a lot. It was a great looking car well representing the era, elegant with dramatic two passenger proportions. The one I saw was silver.

I would imagine that following the Motorama design explosion the 1959 cars were a real challenge for the designers which is evident in what they were doing as seen above. The character of Bill Mitchell’s cars were very different than Earl’s.

DICK RUZZIN

An added note about Ford creating clay models of GM cars in clay.

Several years after the 1992 Cadillac Seville came out a Ford designer told me that Ford Desgn had made a full size clay model to evaluate. I asked him how they liked it and he said the did not. An example of the different design cultures that existed at that time, still so I am sure.

An added note about Ford creating clay models of GM cars in clay.

Several years after the 1992 Cadillac Seville came out a Ford designer told me that Ford Desgn had made a full size clay model to evaluate. I asked him how they liked it and he said the did not. An example of the different design cultures that existed at that time, still so I am sure.

Gary – I look at the Dean’s Garage website every few days and really like the sidebar “Posts from the Archives.

Dick Ruzzin – We must not forget the influence of GM President Harlow Curtice in the development of the final 1959 models. While Harley Earl was in Europe, Curtice visited GM Styling almost every day. He had a favorite designer in Pontiac Studio (Mueller) that he “arranged” to be transferred to the Buick Studio which was dear to Curtice’s heart since he had come from Buick.

It was Curtice who dictated that Buick doors would be used by all divisions, hence the various rear quarter treatments for the other Divisions.

This was a time of great uncertainty when Earl came back from Europe. My belief was that Earl did not know how to respond to Exner’s “1957 Forward Look” and was actually relieved when he saw what had been accomplished in his absence.

XP-75 Models – These were built by Pinin Farina in Italy. George Ryder, a very smooth talking Interior Studio Engineer, was sent to Italy to coordinate the build. At the conclusion of the project, Ryder resigned from GM Styling and opened up a Pinin Farina office north of Oakland Mall.

There was always speculation the Sergio Pinin Farina was hopeful of replacing Earl, but that goodness, Bill Mitchell became the next GM Styling Vice President.

Ken Pickering

Obviously Dean’s Garage is the “master class” of discussion on auto design and US auto design in particular. Really interesting to hear the fact points stated about the how/when/where/why of car design from an era when American auto design for the average man was unsurpassed by hardly any marque. I mean, Cadillac wasn’t blowing smoke when they called the marque “The Standard of the World”. The backside is that it hurts to see how the howling wind of change coming in the Seventies was still thought to be a wind that would pass – and that now Americans no longer look to their own cars first. Do we have another Ed Welburn ready?

1958, ’59, ’60… and yet the stylists could deliver killer-good-looking family cars like the ’55, ’57, ’65-’69…

And someone at GM designed the absolutely gorgeous ’62 Corvette.

Funny how Chevrolet stylists toyed with separating the quad lights. Oldsmobile went ahead with the controversial design that year, and echoed it many more times as a defining cue of the marque. Leading some to believe Olds had the ‘leftovers’ from the other divisions. The rear clip of the Olds was inspired in my opinion, as were all of GM’s offerings in ’59.