by Ron Will

Thanks to Ron Will for providing an original XP-898 brochure, sketches, and this short account of the XP-898.

It’s been many years, but I will do my best to recollect how the XP-898 came about. It actually started with the “Worlds First All Plastic Car” built in 1967 by the German Bayer Chemical Company. The BMW powered car had no metal chassis, only a foam sandwich frame and body built like a surfboard with a fiberglass outer shell and a fiberglass lower shell. Only the engine and transmission were metal. GM knew about the car because they were working with Bayer to develop the very first RIM (Reaction injection molded) parts for cars. The 1969 Pontiac Trans Am Spoiler was the first part created with the RIM process. New bumper regulations opened up a new chance for Bayer-Mobay RIM foam bumpers with the first appearing on the 1975 Monza.

At the same time Chevrolet Engineering was experimenting with their own foam sports car. Ed Mertz was the Chief engineer and a young 25-year-old Brook Lindbert was the Project engineer. The engine and drive components were from the Chevy Vega. The Vega tail lights were the only visible link to it’s underpinnings. The first notch back roof prototype was more of a testing mule. The car was rough and made mostly for testing purposes, and extra nose pieces were made for crash testing. I was told that the moment the nose hit the crash barrier, the room turned into a snowstorm of rigid urethane foam as it burst into thousands of tiny pieces. The tests were quite successful because the foam completely absorbed the shock of the crash. In such a crash the rest of the car should have no damage and the passenger compartment would stay intact. I was told that it would be possible to saw off just the damaged section and glue on a new part.

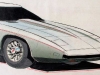

GM Styling was able take advantage of the prototype by building a show car out of it. In Chevy III studio I helped design a new more finished coupe body from the test car. The changes primarily included a more realistic front end, rear end and a new fast back lift-off hard top design. The final model was a basic, clean, simple design that showed well in the car shows. If you look at the prototype, there are no cut lines for the front or rear bumpers. The concept was that as the body was molded, the ends would be soft for the bumpers and then blend into rigid structural urethane further back. Road & Track ran a 6-page article on the car saying it would be good competition for the Datsun 240Z and all 4-cylinder European sports cars.

The project really had no future technologically because the production process would be too slow for a mass producer like GM. Each FRP body shell had to be placed into a heavy mold that was bolted together to sustain the high pressure of the urethane foam injection process. The body would then have to sit for 15 minutes in the mold while it cured. While this was entirely too slow a process for GM, light bulbs went off in two people at GM, John Delorean and myself. John saw this technique as a perfect way to start his new car company. I saw the same idea and stupidly thought I could do the same. John Z left GM to create his Delorean and I left about the same time to create my Turbo Phantom. If you look under the stainless steel skin of the Delorean, you will see the FRP with foam injection used to create crash panels on the side, front and top. His initial idea was to make the car entirely of foam just like the XP-898, but that was changed with the chassis development by Lotus. The Phantom was more true to the XP-898 in that my body and chassis was entirely a foam sandwich design. I think the concept of the foam sandwich car is still viable for a limited production vehicle. The tooling is relatively inexpensive. It is rigid, crashworthy and lightweight, all attributes that we still strive for today.

I don’t know who did the original design for the notch back prototype. The rough prototype car was brought into Chevy III and a platform was set up right in front of my desk. The show car version was mostly a face lift of the prototype. We did the clay work right over the fiberglass model as most of the design was additive. The design was simple and as a show car we had a short deadline. The car was modeled in a matter of weeks and then sent to the shop for completion. The new clay sections were cast in plaster to make fiberglass parts. The new parts were bonded right over the top of the original car. The most complicated part was the new fastback glass hatch. I later worked on the 1978 Corvette glass hatch facelift that was similar but more tapered in the back.

Randy Wittine and John Q. Adams were in the studio at the time, but I think I did most of the work on the car and helped direct the clay model. All of the Monza, Vega and Camaro work was going on at the same time, so everyone was busy and this was an extra job. Jerry Palmer was the chief and the assistant chief was Ted Schoeder. I still have some of the sketches for the 898. Most of the sketches are not full cars but just the details for the modelers to work from. I think the only full drawings of the car were full size airbrush drawings.

In one of the last photos at the bottom in the GM? Collection? What’s the Red Roadster in the background to the front of the Car?

The red roadster is the Monza SS.

Ron and I were summer interns together at General Motors in the mid-60’s. During the 80’s, 90’s and early 2000 we worked together on various Subaru projects (Ron as Design Director myself as Design Consultant) … Impreza, Legacy, WRX, and many others. Recently a computer virus completely wiped out my contact list and even the experts have not been able to retrieve it. I would greatly appreciate it if someone could email me Ron’s current email address or contact me at 949-632-8784. Thanks

When you consider the amount of time it takes to build a steel body structure, with all the processes involved, I do not see how molding the finished body including the foam sandwiching could ever be considered as taking too long. Maybe no one ever considered the full time cycle that is involved in building a steel bodied vehicle, i.e. the construction, dipping for rust-proofing, painting, etc. Even if the sandwich construction required painting, I still think the total time cycle would be shorter for the composite construction.

With the demand for increased economy this will likely be the near future for automobile construction.

Actually, I believe the red car in the background of those photos mentioned is the Astro I as opposed to the Monza.

How was the front rotors and shocks attached?

And was the rear attached the same as the front?

Mark

Mark and anyone that is wondering about attachment points. There were steel components incorporated into the fiberglass-foam construction. I suppose aluminum could be used today much like McLaren and others have used with carbon fiber instead of fiberglass.

In light of the construction processes today, there would be no bolting of the forms because robots would be used to lift, maneuver, and close the molding components with considerable force. Bolting would be unnecessary. There is no way a steel or aluminum bodied automobile can be built to the finished degree this was built to in 15 minutes. This would be very viable today.

John, the Astro I is the car parked to the right side of the XP-898 and is not a roadster. If you look at the direct rear view photo of the XP-898 the red roadster is beyond the left front fender of the Astro I that is parked to the right of the XP-898. That would be the Monza SS.