by John Samsen

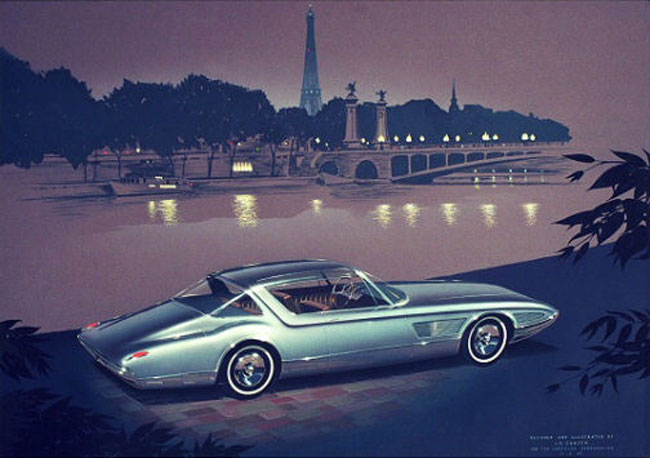

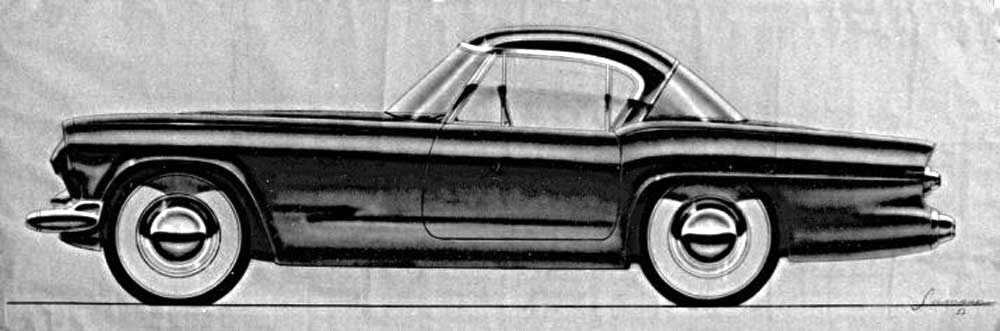

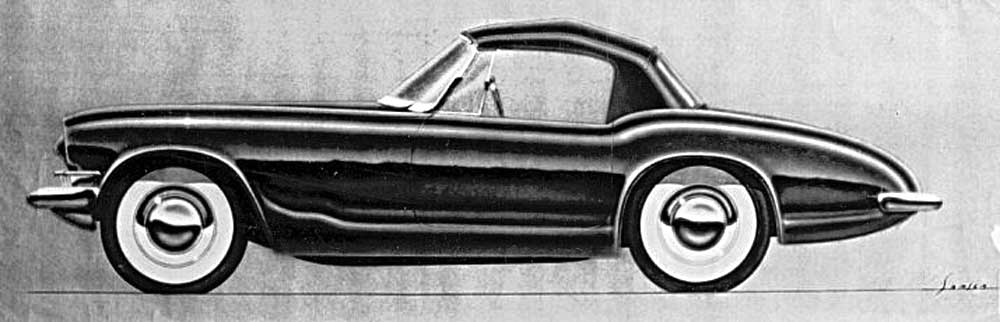

1952 Portfolio Sketch

I was lucky to get into car designing; I was at the right time and place. My early fascinations were with the planes and cars of the ‘thirties and ‘forties, and not knowing anything about Industrial Design, I took an Aero Engineering degree at Purdue, thinking I could “style” aircraft. At McDonnell, I quickly learned there was no place for aircraft design concepts. Later, I met Bob Bourke at the Loewy studios which were in the Studebaker jet engine factory building (Stude was going to produce GE jets, but the contract fell through). Bourke, Andrews, and other Loewy designers coached me in sketching and rendering techniques. As Loewy had no open requisitions, I took my amateurish portfolio to Detroit, and hit Frank Hershey at the right moment.

Being quite interested in sports cars, one day I asked Frank Hershey why Ford was not developing one. He firmly told me that Ford was in business to make money, and the market for sports cars was too small for that. He told me to “forget it.” I was surprised a couple months later when Frank and Damon called the three of us, Bill Boyer, Alan Kornmiller, and myself into a meeting. We were told that we would be designing a two-passenger sports car. There have been many stories about the Thunderbird design program, and most of them have been off the mark. Here is the way it was, from one of the horses’ mouths. It was early 1952. Hershey did have knowledge of the Corvette being designed at GM. He apparently was given a go-ahead to do a design study on a two-passenger car from corporate execs. Body Development was not busy at that time. There was no official design program for it, until early 1953. The design was finished and approved by then. Company records state that the project began in 1953. This is misleading. Our studio was off limits to all personnel except those involved in the project. I saw Henry Ford II and other top execs in the studio several times during the designing in 1952. We designers made full-size side view renderings of our chosen 3/8 scale concepts, and these were mounted on plywood cut to profile.

I was given the task of directing the modeling of the front end, hood, and fenderline of the clay; Bill Boyer was assigned to develop the rear end and windshield of the clay. I worked-out a Ferrari-style scoop and grille. Contrary to some stories, design consultant George Walker and his two designers, Joe Oros and Elwood Engle, were not involved in this project until later, when the body design was set, and we were developing the hardtop.

We had worked out the clay design to the satisfaction of most people concerned, when the project was suddenly cancelled. Engineering would not build these cars in fiberglass, like the Corvette, and to tool in steel would require many sales to cover the cost—more sales than was thought possible. After a few weeks, the clay was returned to our studio, and we were told the project was back on. The word I got was that Henry Ford II insisted on bringing this car out, even if it lost money. Now the sales people wanted it to resemble the standard 1955 Fords as much as possible, so a straight-through fenderline was mandated. Boyer and I held a sweep—a long strip of wood, to the model and knifed in a new fenderline.

Bill changed his rear end design to incorporate ‘55 Ford tail lamps, and brought the form in the rear quarter forward through the door. I suggested bending the line upward and putting a row of louvres next to it, to give it reason for being. I wanted “real” louvres, but the die-cast ornaments were substituted later.

The instrument and door panels were modeled inside the clay model, the modeler sitting on a stool. Interior designers Alex Musichuk and “Gib” Giberson created much of the interior, guided by Art Querfeld, manager of the Ford Interiors studio. Hershey picked some of Ford’s most talented modelers to work on the sports car; Walt Amrozi, Leonard Stobar, Clyde Trombley, Werner Framke, and Mike Nowicki. Initially, a unique panel was designed, but cost considerations decided that the standard 1955 Ford “astra-dial” panel would be used.

From the beginning of the project, a team of engineers worked with the stylists, as well as our two studio engineers Frank Pinkham, whom I had met at Purdue, and John Zimmrerly. First, a cut-down Ford chassis was prescribed, but when some engineers, and we stylists, made a fuss about the car being too nose-heavy, a new frame was designed with the engine moved back about ten inches. Engineering was developing a fuel-injection system at that time, and it was hoped it would be ready for production in time to be used on the little car. I designed a low, sloping hood. Then we were told that we could not count on the injection system, but a new manifold would be designed, allowing the low hood. When the prototype manifold failed to work properly, we then were faced with using the stock manifold, and that would make the carburetor higher than the hood. I thought it would be “neat” to cut a hole in the hood and have a fancy air cleaner stick through it. My sketches of this concept did not sell the idea to management, so the “shaker hood” would have to wait a decade for GM and Chrysler to introduce it on their muscle cars.

I designed a big “blister” on the hood to cover the air cleaner, and added an air scoop on its front surface. Engineering vetoed the grille extending below the bumper, so I lowered the bumper and revised the grille. I added ‘53 Mercury bumperettes to protect the grille. My egg-crate was thought to be too expensive, so I found a piece of perforated steel with square holes, had it chromed, and put in the front. I felt that the design had been “watered down” so much that it was no longer a “sports car.” Boyer and I were proposing concepts for the removable hardtop when Joe Oros, George Walker’s designer, gave a sketch to Frank Hershey. Frank had done his best to keep the Walker group away from the project, but apparently word from top management told him to design this kind of top. Bill and I designed the squarish hardtop similar to Oros’ sketch. We didn’t know until later that Walker had copied it from the Continental Mark II which was being designed at the same time. Before the project was finished, Alan Kornmiller moved to American Motors. Later he went to Chrysler, where he had positions in Styling Management. By early 1953, the little car was finished, as far as the body development.

Obviously, Styling management was aware of this project; it was not a “secret project of Frank Hershey’s, done without the knowledge of management” as some stories have said.

Then the clay went to the Ford Exterior studio, managed by Dave Ash, where the ornamentation and nameplates were designed. Ken Nelson was one of the designers who worked on that phase. During the project, we called the car “Sportsman” and “Sportliner.” Others suggested such names as “Saville,” “El Tigre,” “Denab,” “Coronado,” and “Lightning Rod.” The people involved could not agree to a name until Giberson suggested “Thunderbird.” Everyone liked that name except Henry II, but he finally accepted it.

I was disappointed in the car, until Hershey showed me a sheet-metal prototype. It was no sports car to me. The company decided to call it a “personal car,” which averted controversy. I decided to order one, and went to the Bob Ford dealership in Dearborn. I persuaded the sales manager to take my order for the first one off the line. A year later, I was called, and told I couldn’t have the first one, as it was going to William Clay Ford. I could have number two. By that time, I was planning to go to the Chrysler, having been offered a management position and much higher pay. I turned down the T-Bird!

Unlike some design executives, Frank Hershey was content to let the designers work out their designs without input from him, as long as he and other management people liked what was being created. He occasionally asked for changes when he or others saw fit. I do not recall seeing any sketching from Frank, and if he drew lines on the clay, it would have to be seldom. Damon Woods kept busy with the managing of the studio, and other than his input in meetings, seldom gave design direction on the project. The Ford clay modelers did not belong to a union, and we all got along well together. Boyer and I sometimes sculpted the clay ourselves in working out design problems.

A footnote about George Walker: Most people who had anything to do with George, including me, considered him highly talented in the art of persuasion and promotion. No one I know ever saw a car sketch done by Walker. He had his own design firm and employed Joe Oros and Elwood Engle, both good designers. I once saw Walker do a pen drawing of the profile of a girl’s face. He obviously had practiced it many times, and it was impressive. It reminded me of line drawings my grandfather used to create, having been how in grade school penmanship class. I think Walker was a good judge of car design, and probably helped sell the top execs at Ford the better designs. Frank Hershey highly resented the presence of Walker and his designers, and tried to keep them away from the Thunderbird and 1955 Fords projects. I’m sure that Walker had Hershey fired after George became VP of design in 1956.

Be sure to visit John’s website, Collectable Art.

What an honor to have the true story and recollections of one of the original designers of an American icon—the Ford Thunderbird. Well done!

What a great story. And the last two pictures made my heart skip a beat. That concept DeSoto and the Stude mystery sketch—WOW.

WOW!! What a great story and pictures! I bought my ’56 T-Bird in 1956 when I just got out of service, still have it, and drive it everyday. Just had a new motor installed. 53 years and many miles in all kinds of bad weather. But always garaged. It has sinced retired to Florida, to the warmer weather than the cold north.

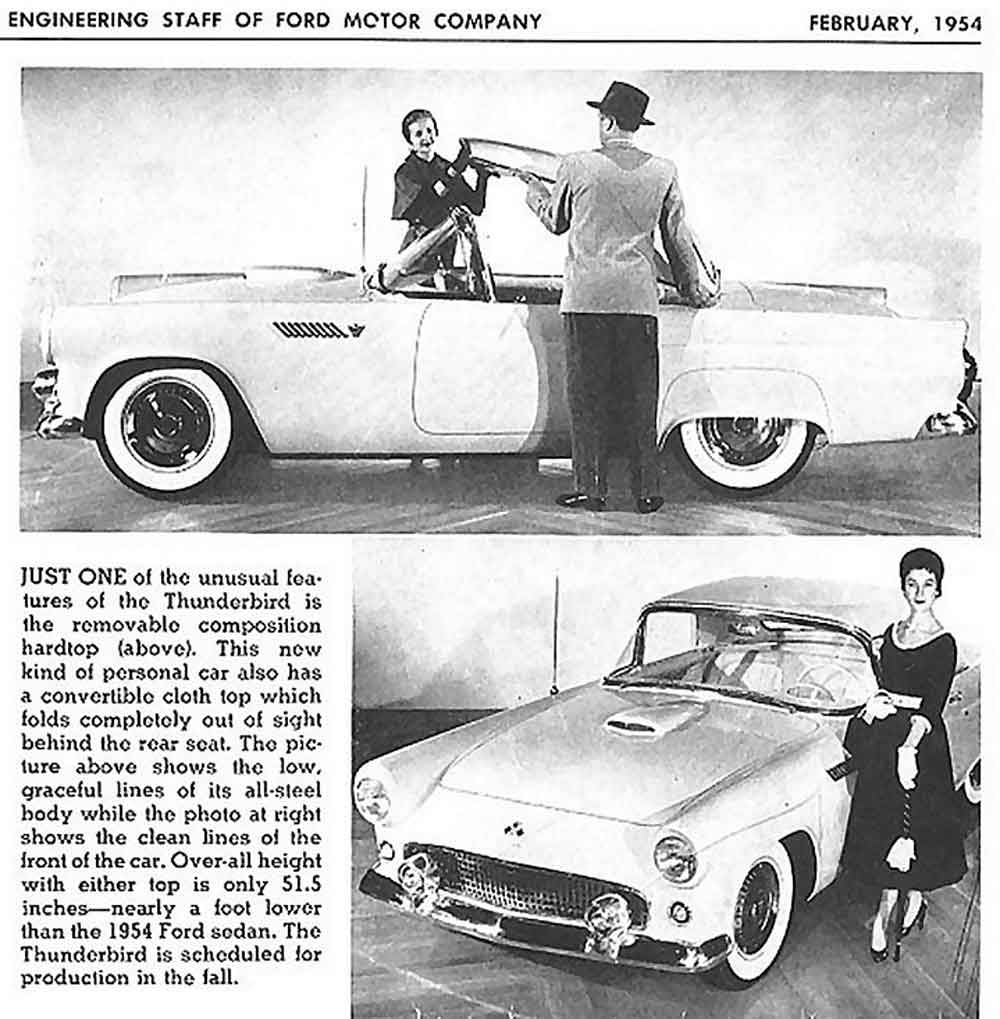

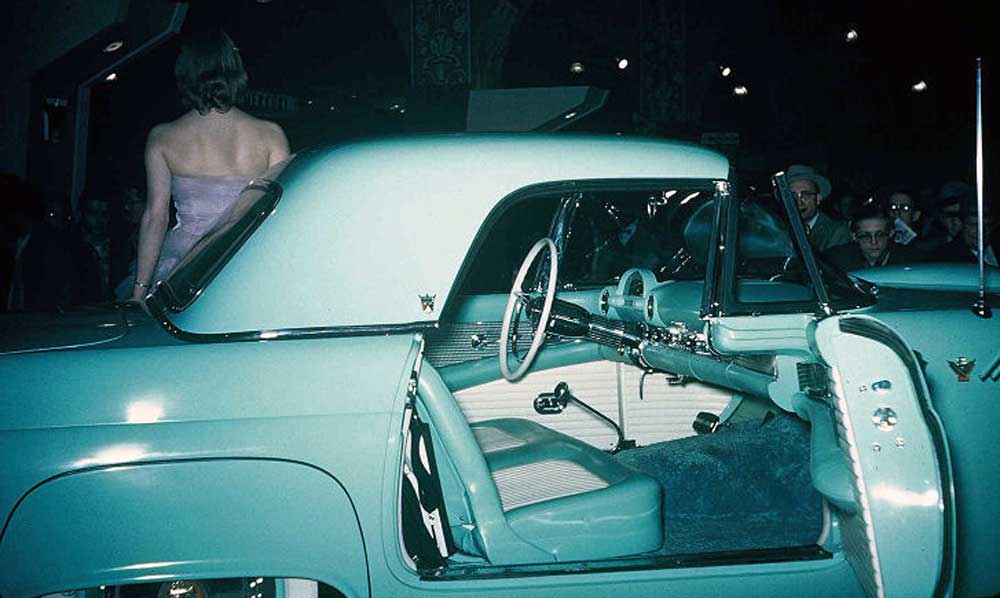

That “mockup” sure looks like the real thing to me. It is not a clay model, even has electric window/seat control on the drivers door. Convertible top folded behind seat, and there is stitching apparent on right armrest. P5FH100004 is Thunderbird blue and has an overdrive transmission, but no electric windows. Could this be the ever elusive P5FH100002 or 3 in picture? Those were Ford Motor Company’s EPVs (Early Production Units—auto show models for display). The last photo in this bunch looks like a ’53 Studebaker customized a bit. It has ’53 Stude wheelvcovers. —mkh

What a great story, and what great photos! Why hasn’t this information been released years ago? Strange! Also, I noticed one flaw in the in the mock-up display at the 1954 Detroit Auto Show. The photo shows a manual shifter, however there does not appear to be a floor clutch—only a power brake pedal!

Robert, some of this info, and pictures, first sppeared in the book Ford Design Dept. Concept and Show Cars 1932-1961 by Jim and Cheryl Farrell, which was published in 1999. The Farrells interviewed hundreds of people who were working in Ford Design Dept. during the T-Bird project.

Previous accounts of the designing of the T-Bird in books and magazine articles were put together from Ford press releases and from interviews with two of the designers involved, Frank Hershey and Bill Boyer, were largely hype. For some reason, the books, magazine articles, and a TV documentary on the ’Bird made it sound as if either Hershey or Boyer had designed the car alone, and failed to mention two other designers involved with the design project—Kornmiller and Samsen. In a recorded interview at the Edsel Ford library of the Ford Museum, Boyer did state “a young gentleman by the name of Dick Samson was in the studio for a while at that time. The major portion of the car—the sketching that was done—was by Dick and myself.”

1959 Thunderbird concept cars?

This comes to you several years after this arcticle was written but I will give it a try anyhow. I have a ’59 T-bird that looks like a custom show car but with fully cut in side vents similar to ones I saw on a sketch attributed to the Advance design studio. The sunvisor on the drivers side has the hand lettered work AVANCIER on it. The roof line has a raised ridge on each side that does so much for the looks of the car but I have never seen another T-bird with that detail. All was done in lead and I have had the car since 1967.

Thank you for any comments you might have.

Sincerely, Mark Mundorff

Great artical and pictures, but just love to look at the few prototypes that had the ’55 Fairlane chrome strips, both above and below the belt line.

The 1954 Auto Show mock-up Bird did not have leading edge chrome trim on the fender skirts. The production cars did. Wonderful article!

Dear Mr. Samsen,

Thanks so very much for this great archival work. When I was a child growing up in Montgomery, Alabama, in the 1950s and 1960s, I used to “compete” with my cousin Lee in car design contests. Lee, a year and half older than I, was an advocate of the General Motors design “philosophy,” while I was convinced that the Ford styling “philosophy” was superior. I always thought I won, and he always gave the nod to himself. My father once sent a very bad drawing of mine of a future Ford Falcon to George Walker, who actually sent me a reply along with a glossy booklet on Ford automobile styling. Lee went on to become an architect, while I got a Ph.D. in philosophy from Johns Hopkins. Now he’s a millionaire; I’m close to destitute. I’ve sketched cars all my life just as a way to avoid boredom.

I’ve always been fascinated by the 1961 Ford lineup, and especially the Bullet Bird, which I think has one of the most perfect designs of any car ever made. It does not have a weak angle and yet has unity, and to me is as exciting today as it ever was. The subtle, pointed but rounded front fender shape in particular has always been a wonder to me. I’ve always wanted to know where it came from — whether it was the product of someone’s sheer inspiration or else evolved from earlier designs. Today, I saw for the first time a side photo of the clay model of the Ford Quicksilver, which is the first design that I know of to have the Bullet Bird front fender. (The Quicksilver concept car has the front fender of the 1961 Ford, not that of the Thunderbird.) I wonder if there are other photos of the Quicksilver clay model. In particular, I would love to see the rear end because I’m curious whether the model had traditional round tail lights or the half moon ones on the production Ford.

Thank you very much again for your invaluable work.

Drayton S. Hamilton

I just discovered this article today. Comments seem to make reference to photos, but I cannot find any. There is a message part way down the page saying “[Not a valid template]” and I wonder if that is where they were? If so can they be restored? Thank you, I enjoyed the article very much.

Robert Joseph Hunt

Have a black ’55 manual shift and love it. This is the only color and year that I desired and am so happy to have it. Once I saw an immaculate ’55 with small fog lights in place of the dual bullets attached to front bumpers. It looked great! More subtle and reminiscent of a lot of European cars. My question is was that the original design intent that got “value engineered” out of the car

or was it never considered?

Great car, I am so thrilled to read from such an authority. I graduated from Art Center in ’79 and know well the aroma of warm clay. I have seen a lot of legends over the years, but this is something of especially keen interest.

Thank you,